Africa File: Political turmoil challenges Mali, Ethiopia, and Tunisia as Libya war heats up

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

Political crises in Mali, Ethiopia, and Tunisia risk destabilizing these countries and creating new opportunities for the expansion of the Salafi-jihadi movement in three African regions. In Mali, the government has cracked down on a mass protest movement calling for the president’s resignation. This crackdown is a dangerous antidemocratic turn and will likely become a recruitment tool for Salafi-jihadi groups in the Sahel, which draw support from populations that suffer persecution by state security forces. In Ethiopia, protests and a subsequent crackdown demonstrate the fragility of the country’s recent political transition and raise the specter of larger instability in the East African economic powerhouse. In Tunisia, the prime minister resigned following corruption accusations in the wake of economic protests.

Meanwhile, Egypt and Turkey are edging toward war in Libya. Diplomatic efforts have stalled over irreconcilable demands as Libyan factions and their foreign backers prepare to fight for a strategic city in central Libya. Foreign involvement has made Libya’s war longer and more violent, increasing harm to civilians, worsening the economic and governance crisis, and prolonging the conditions that allow Salafi-jihadi militants to operate in the country.

Recent Publications

“Webinar — Collapsed caliphate? Understanding the Islamic State in 2020,” July 2020

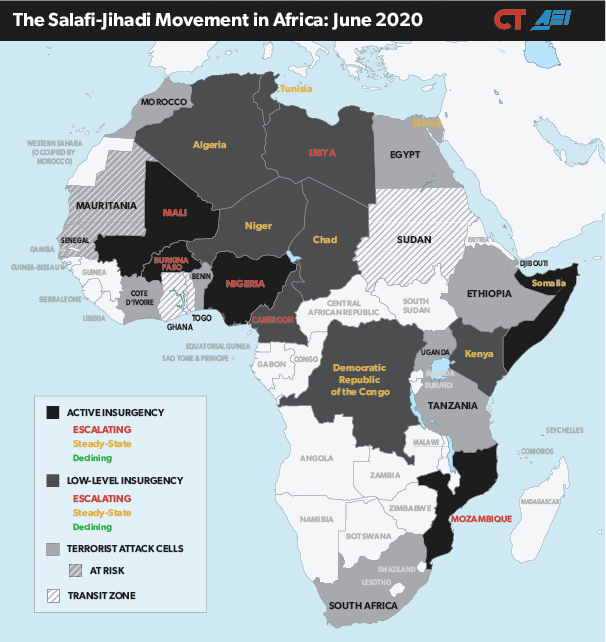

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: June 2020

Source: Author.

Read Further On:

North Africa

West Africa

East Africa

At a Glance: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated July 21, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic will hasten the reduction of global counterterrorism efforts, which had already been rapidly receding as the US shifted its strategic focus to competition with China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. The US administration has begun to withdraw troops from Afghanistan after signing a peace deal with the Taliban on February 29. The future of US forces in Iraq and Syria is uncertain following the destruction of the Islamic State’s physical caliphate and its leader’s death, though the group already shows signs of recovery. The US Department of Defense is also considering a significant drawdown of US forces engaged in counterterrorism missions in Africa, though support for the French counterterrorism mission in the Sahel has been extended for now.

This drawdown is happening as the Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, continues to make gains in Africa, including in areas where previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement was already positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure before the pandemic hit. Now, a likely wave of instability and governmental legitimacy crises will create more opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations.

The Salafi-jihadi movement is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali, where it seeks a negotiated settlement with a Malian government under increasingly intense pressure to address a burgeoning security crisis and the presence of foreign forces. Salafi-jihadi insurgencies are also stalemated in Somalia and Nigeria and persisting amid the war in Libya. Conditions in these last three countries favor the Salafi-jihadi movement rather than its opponents in the coming year.

Libya’s civil war, reignited on a large scale in April 2019, will continue to fuel the conditions of a Salafi-jihadi comeback, particularly as foreign actors prolong and heighten the conflict. Counterterrorism efforts in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding in both host and troop-contributing countries and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in their people’s eyes.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great-power competition, a move also intended to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness—such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown. COVID-19 has exacerbated existing problems with these forces, with contributing nations reevaluating their commitments to foreign intervention during the pandemic.

The Salafi-jihadi movement has several main centers of activity in Africa: Libya, Mali and its environs, the Lake Chad Basin, the Horn of Africa, and now northern Mozambique. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other places is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse (all now likely to be exacerbated by the pandemic). Local crises are the incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the bases for future attacks against the US and its allies.

North Africa

Libya

Turkish-backed forces are preparing to cross Egypt’s “red line” in Libya, increasing the likelihood of direct confrontation between major regional militaries. Libyan belligerents and their foreign backers have been preparing to fight for control of Sirte city on the central Libyan coast since June. Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al Sisi declared Egypt’s right to intervene in Libya on June 20 in a bid to stop Turkish-backed Libyan forces from threatening Sirte and the neighboring “oil crescent” region, a key economic area currently held by the Egypt-backed Libyan National Army (LNA). Turkish support helped forces aligned with the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) end the LNA’s bid to seize Libya’s capital, Tripoli, in May 2020. Libya’s civil war has become an open contest among regional powers, with Turkey backing the GNA and Egypt, Russia, and the UAE among the LNA’s backers.

Preparations for the battle for Sirte have escalated in the past week. The GNA conducted its first major deployment toward the Sirte front on July 19 and has *moved newly delivered Turkish missile systems near Sirte as well. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan promised to fight with Libyans and *declared that Turkey would forge a new agreement with the Libyan government under UN auspices on July 17. In response, Egypt’s parliament rubber-stamped broad authorities for an Egyptian military intervention in Libya on July 20. Egypt may have also *sent military supplies into eastern Libya in July. President Sisi has promised to arm and train eastern Libyan tribal forces.

These preparations indicate that the LNA backers’ efforts to both militarily and diplomatically deter a Turkish-backed GNA offensive have failed. A Russo-Turkish diplomatic channel, including a July 13 call between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Erdogan, yielded no agreement. A July 5 airstrike by an LNA backer struck a western Libyan air base that Turkey may be seeking to convert into a permanent Turkish position.

In response, the Turkish president’s media office stated on July 6 that the Jufra air base south of Sirte, where Russian mercenaries had been stationed, is a legitimate military target. Russia and Turkey announced on June 22 that they would push for a cease-fire, but the Turkish demand—that LNA forces withdraw from Sirte and Jufra—still violates Sisi’s stated red line.

Russian and Sudanese mercenaries are occupying strategic positions to deter a GNA offensive and increase the LNA’s leverage in negotiations. US Africa Command has reported that Russia and the Wagner Group have introduced land mines, booby traps, and attack aircraft to the conflict since May. Russian and Sudanese mercenaries have reportedly mined locations south of Sirte since mid-July before *withdrawing eastward *toward the oil crescent.

Russian and Sudanese forces deployed to Libya’s largest oil field, in the southwest, in late June to prevent GNA-aligned forces from negotiating the resumption of oil production. The LNA and aligned local forces have blockaded oil production from the oil crescent and southwestern Libya since January 2020 to gain leverage over the GNA, which is dependent on oil revenues.

The Libya conflict continues to deepen fissures in NATO, advancing a core Russian objective. Turkey’s ambitions in Libya and the eastern Mediterranean Sea are bringing it closer to military confrontation with Greece and France. Turkey seeks to establish a maritime corridor to Libya that will allow it to exploit undersea hydrocarbon resources. This claim infringes on established maritime boundary claims, including Greece’s.

France asked the European Parliament on July 2 to force Turkey to “realize” it cannot violate NATO rules. France has accused Turkish vessels of harassing a French frigate seeking to inspect their cargo for potential violations of the UN arms embargo on Libya on June 10. Turkey alleged that the cargo ship was carrying humanitarian aid and accused the French vessel of aggression. NATO is investigating the incident.

Turkey is building an enduring military presence in western Libya. Turkish officials are in discussion with their GNA counterparts to establish permanent Turkish air and naval bases in northwestern Libya. The Turkish defense minister announced the intent to form joint military units with Turkish and Libyan GNA personnel during a visit to Tripoli in early July.

GNA leaders are attempting to capitalize on their recent military successes and Turkish backing to take control of western Libya’s fragmented security landscape. The GNA *formed a new operations room to secure roads and key locations in western Libya on July 13. The joint force subsequently ordered militias to leave 12 locations in Tripoli. The GNA Army chief of staff also proposed *integrating pro-GNA militias into a national guard in early July.

The changing political and security landscape in western Libya is also creating opportunities for Islamist political figures to attempt to regain support. Nouri Abusahmain, who led the Libyan national assembly in 2013, *announced the formation of a new political movement called “Ya Biladi (My Country)” on July 6. Abusahmain was previously backed by a Muslim Brotherhood–aligned political party, and Libya’s grand mufti—known for his support for hard-line Islamist armed groups—*endorsed Abusahmain’s new movement.

GNA-aligned forces *dismantled an Islamic State cell in Zawiya, possibly indicating that the group is resuming activities in northwestern Libya following the end of fighting around Tripoli. The incident follows the Islamic State’s resumption of regular attacks and media activity in southwestern Libya after nearly a year of limited attacks and media activity.

Forecast: In the most likely case, fighting will stalemate in central Libya. Egypt may make a show of force to persuade Turkey to scale back its support, limiting the advance of GNA-aligned forces and preserving LNA control of the oil crescent. This de facto partition would likely lead to future rounds of civil war and proxy conflict after the combatants rearm.

In a less likely but more dangerous case, a miscalculation or error could draw external forces into direct conflict, possibly including conflict between two US allies (NATO ally Turkey and major non-NATO ally Egypt).

Either case preserves and worsens the conditions that allow Salafi-jihadi groups to strengthen. The Islamic State will likely continue its renewed attack tempo and may resume intermittent attacks targeting symbolic state institutions in coastal cities in the coming months. (Updated June 24, 2020)

Tunisia

Tunisia faces a political crisis following the resignation of Prime Minister Elyes Fakhfakh. Fakhfakh abruptly resigned following allegations of conflict of interest and corruption, triggering a new government formation process and potentially another election less than five months after a divisive government formation. Fakhfakh denied allegations of wrongdoing but stepped down on July 15 after the leading Islamist party, Ennahda, withdrew its support for the prime minister and backed a no-confidence petition in parliament. Fakhfakh, who will lead a caretaker government, fired several Ennahda ministers in retaliation.

The political crisis comes amid intense economic protests. Police and protesters clashed in June after the arrest of an activist. Tunisia’s economy suffers from high unemployment, inflation, and living costs, which the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated. Demonstrators in southern Tunisia closed an oil pumping station to protest joblessness on July 16.

West Africa

The Western Sahel

A political crisis is destabilizing Mali. Large protests calling for the resignation of Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita have gripped the country’s capital, Bamako, since early June. The protests are a response to economic problems, perceived government corruption, and a failure to contain a burgeoning Salafi-jihadi insurgency, which disrupted legislative elections earlier in 2020.

The protest movement’s leader is Mahmoud Dicko, a prominent imam and former ally of Keita who rose to prominence as an advocate for public morality and has acted as an intermediary in prior negotiations with Salafi-jihadi groups in northern Mali. President Keita has made some concessions to protester demands, including judicial and legislative reforms, that have failed to quell the movement, particularly as security forces have ramped up a violent crackdown on protesters.

The Malian government has embraced authoritarian tactics in response to protests. Security forces have killed at least 14 protesters and injured dozens more in July. The Malian government has also restricted access to social media and messaging platforms in Bamako and detained several opposition leaders. The Malian government has *deployed its Special Anti-Terrorism Force, which is intended for rapid responses to terrorist attacks, to crack down on protesters.

Protests are temporarily paused for the Eid al Adha holiday and external mediation. Opposition leaders agreed to a “truce” on July 21. West African heads of state are traveling to Mali for mediation efforts, days after protest leaders rejected a unity government proposed by regional leaders that would include Keita.

The use of counterterrorism forces against protesters will further destabilize and delegitimize the Malian state. Security force abuses may create new opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to recruit disillusioned individuals, though Salafi-jihadis’ reach will likely remain limited in Bamako itself. Should the crisis intensify, the Malian government may draw more security forces into the capital, creating more opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to take de facto control over parts of northern and central Mali, including regions bordering the capital.

Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s Sahel affiliate is likely escalating attacks on Dogon civilians in central Mali to reignite ethnic violence in Mopti region. Suspected JNIM militants have *killed dozens of civilians in attacks on Dogon villages in Mopti since early July. Clashes between armed Fulani groups backed by JNIM and Dogon groups backed by the Malian army are frequent in Mopti despite cease-fire agreements negotiated in August and October 2019. JNIM has exploited and inflamed ethnic conflict in central Mali to gain popular support from vulnerable Fulani populations and establish itself as a security guarantor and power broker in central Mali.

JNIM may also be resuming attacks in northern Burkina Faso after a month of sustained counterterror operations by the Burkinabe army. Suspected JNIM militants ambushed a convoy traveling near a village in Sanmatenga province on July 6. This is the first militant attack in Burkina Faso since an attack on an aid convoy in the same area in late May. No group has claimed either attack. JNIM was active in this area earlier in May[1] and may seek control over a north-south road through Sanmatenga as part of a larger effort to isolate northern Burkina Faso.

Civilians and human rights organizations have uncovered more evidence of human rights violations by Burkinabe security forces. Burkinabe civilians have found at least 180 bodies in graves around Djibo town in northern Burkina Faso over the past eight months, according to a Human Rights Watch report. Residents blamed Burkinabe security forces for the deaths, noting that the men killed were mostly members of the Fulani ethnic group. Security forces have regularly targeted Fulani members over accusations of cooperating with militants.

Burkinabe military forces also killed seven civilians in a military operation in eastern Burkina Faso in late June. Abuse by security forces is a key driver of Salafi-jihadi recruitment; these recent allegations will continue pushing locals to support militant organizations for protection. (For more detail, see “How Ansar al Islam gains popular support in Burkina Faso.”)

US Department of State Spokesperson Morgan Ortagus warned on July 8 that US security assistance to Sahel countries will be at risk if it is used to violate human rights.

Countries bordering western Sahel states are increasing security measures to counter Salafi-jihadi threats. The Ivorian military declared a special defensive military zone in northern Cote d’Ivoire to prevent Salafi-jihadi militants from infiltrating the country. This announcement followed a likely JNIM attack on an Ivorian military base along the country's border in June. Senegal also began *building a military camp on the Malian border to counter Salafi-jihadi groups and trafficking.

Forecast: The political crisis will fuel unrest with interest groups in northern Mali, possibly distracting the state from counter-Salafi-jihadi efforts and creating more opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to establish mutually beneficial agreements with other anti-government groups. Salafi-jihadi groups will begin to establish governing institutions—such as courts—in the Burkinabe-Malian-Nigerien tri-border area, though they may mask these efforts to facilitate a deal with the Malian government.

Salafi-jihadi groups may also work through local governance structures to present themselves as legitimate interlocutors and avoid scrutiny. Attacks on Fulani civilians will drive greater popular support to JNIM, which will present itself as a security provider.

The national political crisis will lead to negotiations between the Malian government—either the Keita administration or a successor—and JNIM. (Updated July 21, 2020)

The Lake Chad Basin

The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) is carrying out multifront operations to secure its freedom of movement, deter security forces, and establish a large haven in the Lake Chad Basin. ISWA *attacks on military and civilian *convoys in June and July indicate that it seeks to isolate the capital of Borno state in northeastern Nigeria. The group also *targeted military convoys in the Lac region of Chad in July, signaling an effort to deter Chadian military forces from operating outside their bases. ISWA likely participated in a March attack that killed nearly 100 Chadian soldiers and indicated a new focus on targeting Chad.

East Africa

The al Shabaab insurgency in Somalia is largely stalemated, but conditions—including political instability and the planned withdrawal of African Union peacekeeping forces—are evolving in al Shabaab’s favor. Severe unrest in neighboring Ethiopia could also create opportunities for al Shabaab and the Islamic State in Somalia, which plotted attacks targeting Ethiopia in 2019.

Somalia

Al Shabaab is conducting an assassination campaign targeting prominent Somali government and military officials, underscoring the Somali government’s inability to secure the capital Mogadishu. An al Shabaab militant detonated a suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (IED) targeting Somalia’s Army Chief of Staff Odowa Yusuf Rage as he departed the Ministry of Defense in Mogadishu on July 13. Rage is known for personally leading attacks against al Shabaab before his 2019 appointment as chief of staff.

Al Shabaab conducted another IED *attack targeting Somalia’s deputy security minister in Mogadishu on July 18, according to Somali government officials. Al Shabaab previously *conducted a mortar attack targeting the recently refurbished Mogadishu Stadium hours after Somali President Mohamed Farmajo presided over its opening ceremony on July 1. The attack may have intentionally coincided with the 60th anniversary of Somalia’s independence.

Al Shabaab’s uptick in assassinations has also targeted officials outside the capital, as Caleb Weiss demonstrates.

The Somali army has pushed al Shabaab out of multiple villages near the major port city of Kismayo in southwestern Somalia’s Lower Jubba region, disrupting al Shabaab’s ability to attack the city. A military spokesman *announced on June 24 and 28 that Somali special forces *captured eight villages from al Shabaab near Kismayo. Kismayo’s port served as al Shabaab’s main source of income before African Union and Somali troops drove the insurgency from the city in 2012. Al Shabaab maintains a strong presence within the rural areas of the Lower and Middle Jubba regions. Pushing al Shabaab from these villages deprives it of areas to plan and stage attacks on larger Somali cities.

Forecast: Al Shabaab will continue to conduct assassination attempts targeting high-value Somali military and political leaders in Mogadishu. The assassination of senior officials could disrupt ongoing negotiations between the Somali Federal Government and federal member states concerning upcoming elections. (Updated July 21, 2020)

Somaliland, which claims independence from Somalia, formally recognized Taiwan’s independence on July 1. China’s foreign ministry accused Taiwan of “undermining Somalia's sovereignty and territorial integrity.” The US National Security Council congratulated Taiwan for establishing ties with Somaliland. Both China and the US maintain military bases in the neighboring country of Djibouti and compete for partnerships in the Horn of Africa.

Ethiopia

The assassination of a popular Ethiopian singer led to renewed political turmoil along ethnic lines in Ethiopia. Thousands protested and rioted across the Oromia region, accusing the government of involvement in the killing. Ethiopian security forces *killed at least 150 protestors during a crackdown against the protests. A fraught political transition and Ethiopian President Abiy Ahmed’s ambitious reform program have inflamed deep ethnic fissures in Ethiopian society, including within his own Oromo community. Protests, riots, and violent government crackdowns could destabilize the state and spread to ethnic Somali communities in southern Ethiopia, opening opportunities for al Shabaab to exploit local grievances and expand into the East African powerhouse.

Mozambique

The Islamic State threatened South Africa preemptively in response to potential military intervention in Mozambique. The Islamic State warned[2] on July 3 that it would open a “fighting front within [South Africa’s] borders” should South Africa become more involved in Mozambique. South Africa’s Democratic Alliance party released a statement on July 6 urging the South African government to decisively deal with Islamic State–linked militants in northern Mozambique by deploying South African National Defence Force and African Union forces. The Dyck Advisory Group, a South African private military company, is active in northern Mozambique.

Forecast: The Mozambican Islamic State branch will attempt to take control of a Cabo Delgado population center and declare it a part of the Islamic State’s caliphate this year. (As of June 23, 2020)

[1] “JNIM Claims Rocket Strike on Foreign Military Camp in Mali, Ambushing Soldiers in Burkina Faso,” SITE Intelligence Group, May 26, 2020, translation available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[2] “IS Says Western Powers “Delusional” to Think Natural Gas Resources Safe in Mozambique, Warns South Africa Against Military Role,” SITE Intelligence Group, July 3, 2020, translation available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.