Africa File: Al Shabaab highlights US withdrawal after attacks on Somali special forces

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Al Qaeda affiliates in eastern and western Africa are advancing toward their objectives amid ongoing drawdowns of international counterterrorism missions on the continent. Al Shabaab, al Qaeda’s Somalia-based affiliate, emphasized the recently completed withdrawal of US troops from the country in its messaging about recent attacks on US-trained Somali special forces. Al Shabaab is also positioned to disrupt Somalia’s elections, as the country faces a potential constitutional crisis. Al Qaeda–linked militants in the Sahel region of West Africa are deepening their control over terrain and populations in central Mali and may be preparing to expand operations into Gulf of Guinea countries. Public support for the French-led counterterrorism mission in the Sahel is waning in both France and Mali.

In this Africa File:

- Somalia. An al Shabaab propaganda campaign is attempting to exploit the US withdrawal from Somalia by emphasizing attacks on US-trained Somali special forces. Discord between Somalia’s federal and state governments threatens national elections and is heightening regional tensions.

- Ethiopia. The conflict between Ethiopian federal forces and Tigray regional state forces may be resuming in the country’s north.

- Mozambique. Mozambique’s president reshuffled top security leaders in mid-January in a bid to revitalize faltering counterterrorism efforts.

- Sahel. An al Qaeda–linked group is progressing toward its goal of replacing governance structures by occupying and allying with villages in central Mali.

- Lake Chad. The Islamic State’s West Africa Province deployed a rarely used explosive attack capability along the Nigeria-Niger border.

- Libya. Foreign forces remain likely spoilers to a political resolution in Libya.

Latest publications:

- Somalia. Katherine Zimmerman argues that the Joe Biden administration should reverse the Donald Trump administration’s withdrawal from Somalia to stave off a worst-case possibility: al Shabaab conducting a transnational mass-casualty attack. Read her argument here.

- The Salafi-Jihadi Movement. Emily Estelle argues that viewing the al Qaeda threat through the prism of Iran masks the reality of the threat—including in Africa—and drives the US farther from an effective counterterrorism policy. Read her op-ed, originally published in The Hill, here.

- Ethiopia. CTP is publishing updates on the Ethiopia crisis. Sign up to receive the latest updates by email here. Read Jessica Kocan’s latest update here and Emily Estelle’s background on the conflict here.

Read Further On:

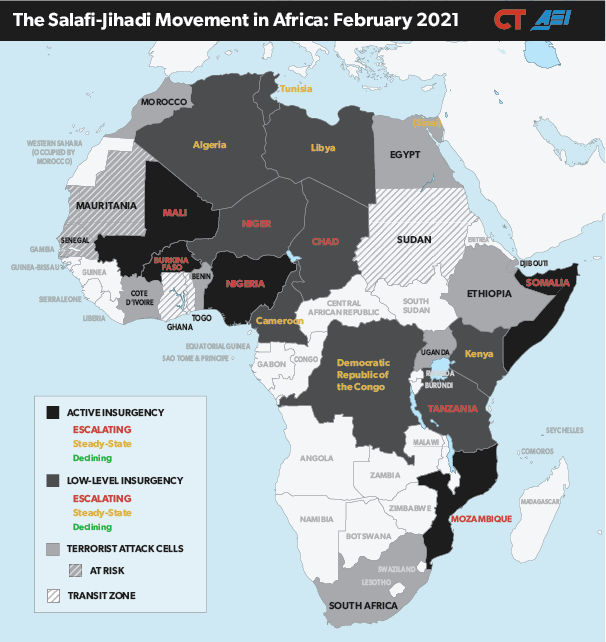

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: February 2021

View full image.

Source: Emily Estelle.

Overview: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated February 3, 2021

The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is active across northern, eastern, and western Africa and is expanding and deepening its presence on the continent. This movement, like any insurgency, draws strength from access to vulnerable and aggrieved populations. Converging trends, including failing states and regional instability, are creating favorable conditions for the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion. Meanwhile, continued counterterrorism efforts rely on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding, and on states and local authorities that have demonstrated an inability to govern effectively.

West Africa. The Salafi-jihadi movement has spread rapidly in West Africa by exploiting ethnic grievances and state weaknesses that include human rights abuses, corruption, and ineffectiveness. An al Qaeda affiliate co-opted the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and has continued to expand southward through the Sahel region into central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. Sahel groups have not yet plotted attacks outside of West Africa but have sought to drive Western security and economic presence out of the region while building lucrative smuggling and kidnapping-for-ransom enterprises. An al Qaeda–linked group in Mali is infiltrating governance structures, advancing an overarching Salafi-jihadi objective, and seeks to expand into Gulf of Guinea countries. West Africa has become an area of focus for transnational Salafi-jihadi organizations, with rival jihadists now fighting for dominance in the Sahel.

The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate is based in northwest Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—and conducts frequent attacks into neighboring states. Boko Haram and an al Qaeda–linked splinter group are also active in this region.

East Africa. Al Shabaab, an al Qaeda affiliate and the dominant Salafi-jihadi group in East Africa, is vocal about its intent to attack US interests and has begun to plot international terror attacks. The group enjoys de facto control over broad swathes of southern Somalia and can project power in the Somali federal capital Mogadishu and regional capitals where it regularly attacks senior officials. It seeks to delegitimize and replace the weak Somali Federal Government—a task made easier by endemic political dysfunction and corruption in Mogadishu. Al Shabaab’s governance ambitions extend into Kenya and Ethiopia, as it claims to seek to unite the Somali ethnic group.

Al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from eroding security conditions in East Africa. Ethiopia’s destabilization is already having regional effects, including weakening counter–al Shabaab efforts inside Somalia. The drawing down of the US and African Union counterterrorism missions in Somalia will also reduce pressure on al Shabaab.

The Islamic State has also penetrated the region. Islamic State branches are now active in northern Somalia, the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Mozambique bordering Tanzania, where its affiliate seized a Mozambican port in August 2020 that it still controls. The Islamic State foothold in Mozambique marks the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion into southern Africa.

North Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups in North Africa are at a low point, but the fragility and grievances that led to their rise remain. The Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent security vacuums allowed Salafi-jihadi groups to organize and forge ties with desperate and coerced populations. The rise of the Islamic State brought a peak in Salafi-jihadi activity in North Africa, particularly from its branches in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Counterterrorism pressure has weakened Salafi-jihadi groups across North Africa in the past five years. The insurgencies in Libya and Sinai are active but contained, and terrorist attacks across the region have decreased. Libya’s war will continue to create opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups, and severe instability or collapse in any North African state would likely bring the Salafi-jihadi threat back to the surface.

East Africa

Somalia

Somalia’s security and political conditions are eroding in al Shabaab’s favor. US Africa Command withdrew troops from Somalia in mid-January. Somalia’s political tensions with neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia’s domestic crisis are also disrupting security efforts as both countries support the counter–al Shabaab fight. These trends are lifting pressure from al Qaeda’s East African affiliate at a time when Somalia is preparing for fraught elections.

An al Shabaab propaganda campaign is attempting to exploit the US withdrawal from Somalia by emphasizing attacks on US-trained Somali special forces. Al Shabaab claimed to be intensifying attacks on US-trained Somali Danab special forces on January 17, noting that this escalation coincides with US troop withdrawal.[i] The group targeted a Danab convoy with an improvised explosive device near Wanlaweyn town in southern Somalia’s Lower Shabelle region the same day. Al Shabab *falsely *claimed to kill a Western officer in this attack.[ii] Danab also preempted a potential al Shabaab attack by *destroying a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device in Lower Shabelle region on January 8.

Al Shabaab’s rate of attack on Danab forces has not increased significantly compared to 2020, however, despite the group’s claims to have intensified attacks. An uptick in al Shabab–Danab engagements is due instead to a surge in counter–al Shabaab operations, including *targeting al Shabaab bases in Bay region in early January and *reclaiming territory in Lower Jubba region in late January. Somali special forces have increased counterterror operations at least twofold since December. This surge may reflect an effort to complete actionable operations before the withdrawal of most US troops in Somalia, which the Pentagon announced in December and completed on January 13. The US continues to provide Danab with air support and maintains a limited force presence in Somalia.

Discord between Somalia’s federal and state governments threatens national elections, scheduled for February 8, and is heightening regional tensions. Jubbaland state in southwestern Somalia is one of two states that refused to participate in the elections since late 2020. Somali Federal Government (SFG) forces and Jubbaland forces clashed on January 25, *killing at least 11 people, including nine civilians. Violence between SFG and Jubbaland state forces in February 2020 displaced more than 50,000 people from Jubbaland’s Gedo region.

Negotiations may stave off further violence in the near term; Jubbaland since agreed to participate in the national electoral committee, a sign of progress toward a potential election agreement, on January 27. A constitutional crisis remains likely, however. The SFG’s presidential and parliamentary mandates expire on February 8, and it is likely impossible to complete elections before this deadline.

Renewed violence in Gedo region creates opportunities for al Shabaab to expand in the Kenyan-Somali border region and in northeastern Kenya’s Mandera County. Al Shabaab exploited the February 2020 clashes by resuming attacks in Gedo region’s Bardhere town after a yearslong lull.

The SFG-Jubbaland tensions have contributed to a sharp downturn in Kenyan-Somali relations. The Kenyan government supports Jubbaland’s president and security forces. Tensions between the two countries spiked in November 2020 when Somalia’s Foreign Affairs Ministry *dismissed Kenya’s ambassador to Somalia, accusing him of pressuring Jubbaland’s president to renege on an agreement to hold federal presidential elections. Somalia accused Kenya of supporting Jubbaland state forces during the most recent *clashes. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), an East African eight-country trade bloc, began an investigation into Somalia’s allegations against Kenya but dismissed them, causing Somalia to threaten withdrawing from IGAD.

Forecast: Al Shabaab will increase attacks in Mandera County to expand its reach into northeastern Kenya. Al Shabaab regularly targets civilians and communication infrastructure in Mandera County to disrupt security forces’ response. (As of February 2, 2021)

Al Shabaab is demonstrating its ability to target high-level officials and disrupt Somalia’s upcoming presidential elections. Al Shabaab detonated a suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device at a hotel entrance in the Somali capital, Mogadishu, on January 31. Al Shabaab gunmen then stormed the property, killing at least five people including a retired Somali military officer. Al Shabaab targeted the former general for his role in killing several al Shabaab militants, including a senior commander.[iii]

This attack also signals al Shabaab’s ability to target senior officials during the election season. Al Shabaab has disrupted previous election cycles and is ramping up its targeting of the upcoming elections. The group *fired mortars in Dhusamareb, the capital of Galmudug state, on February 2 during an emergency preelection meeting between the SFG president and federal state leaders.

Forecast: Al Shabaab will continue targeting electoral meetings and political officials leading up to Somalia’s presidential elections scheduled for February 8. (As of February 2, 2021)

Ethiopia

The conflict between Ethiopian federal forces and Tigray regional state forces may be resuming in the country’s north. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) leader made his first statement in months on January 30, urging Tigray residents to “continue the struggle,” implying TPLF members continue to fight against federal troops and allied militias. Ethiopian federal forces have controlled Tigray’s regional capital, Mekelle, since late November. A Belgium-based nongovernmental organization reported that fighting has begun in areas northwest of Mekelle. This report is uncorroborated and information from Tigray remains limited. If confirmed, however, renewed fighting in Tigray would contradict the Ethiopian federal government’s claim that Tigray has returned to “normalcy.”

Somali civilians have protested the alleged deployment of Somali soldiers to Tigray. Soldiers’ families have shared stories of the SFG recruiting their sons for security work in Qatar only to force them to join forces in Eritrea that then deployed to Tigray. A Somali parliamentary official urged Somalia’s president to investigate these allegations. Ethiopia’s foreign ministry spokeswoman and Somalia’s *information minister denied Somali troop involvement in Tigray.

Mozambique

Mozambique’s president reshuffled top security leaders in mid-January in a bid to revitalize faltering counterterrorism efforts. Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi appointed a new chief of the general staff in mid-January. The reshuffle comes after Islamic State–linked militants advanced toward a foreign natural gas facility in the country’s northern Cabo Delgado province in January. The attacks led French company Total to reduce its workforce at the facility and spurred rumors that the company would move its logistics base off of Mozambique’s mainland. The government has also been cracking down on journalists covering the conflict. Mozambique’s Migration Service *deported a British journalist who had been extensively covering the insurgency on January 30.

Militants launched an insurgency in resource-rich Cabo Delgado province in late 2017. The group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2019 and has maintained control of a provincial port since August 2020. Mozambican forces have struggled to regain territory from the militants who began limited cross-border attacks into neighboring Tanzania in October 2020.

West Africa

Sahel

An al Qaeda–linked group is making progress toward its goal of replacing governance structures by occupying and allying with villages in central Mali. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) *signed agreements with over 60 villages in Niono in central Mali’s Segou region in mid-January. JNIM began *occupying villages in central Mali in September 2020, intensifying its effort to become a governing force in an area where the group has been present for years.

JNIM has now *gained control over large parts of Niono despite recent counterterrorism pressure in the area. JNIM gained influence in Niono by *threatening villagers and *starving populations in the regions outside its direct control by *preventing villagers from accessing their agricultural fields or traveling to neighboring villages. Suspected JNIM militants *burned several agricultural fields in Niono’s Dogofry village in early January. JNIM is exploiting fear and *poor economic conditions in Niono to gain access to agricultural *resources and cement its presence in the Niono region. JNIM has also *appointed a judge and local representatives for the Niono area.

The Malian government’s prisoner release in October 2020 may have contributed to JNIM’s growing entrenchment in central Mali. The Malian government released hundreds of prisoners in an exchange with JNIM in October 2020, including over 100 suspected militants in Niono. The release of former prisoners, which likely included JNIM members and unaffiliated individuals, may have augmented the group’s existing presence around Niono and created an opportunity for JNIM to gain favor with communities. JNIM previously negotiated its presence with local leaders in Farabougou village, which the group occupied in early October 2020, and will likely continue exploiting village resources in exchange for peace.

French and Malian political dynamics are reducing support for the French-led counterterrorism mission in Mali. A Malian civil society group organized a *protest against French presence on January 20. The group called for the protest after accusing French forces of striking civilians during a wedding party amid confusion over an unclaimed attack in central Mali’s Bounti village in January. Malian security forces forcefully dispersed the rally in Mali’s capital, Bamako. Mali’s transitional president, Bah Ndaw, reaffirmed support for the French counterterrorism mission the day before. French President Emmanuel Macron also met with President Ndaw a week after the protest to discuss joint security operations.

Anti-French protests are a potential source of instability in Mali’s postcoup political environment. Anti-French protests contributed to political instability and popular dissatisfaction surrounding the August 2020 coup that ousted President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. Mali’s transitional government has since pledged to strengthen governance and combat corruption. Protests in Bamako could pressure Mali’s transitional government to reconsider supporting French presence as it plans for presidential *elections in early 2022 per the transitional government agreement.

Support for the French Operation Barkhane may also be waning in France. France has begun to reduce its troop presence in Mali by integrating European forces. Discussion of withdrawal will likely increase as France approaches the 2022 presidential elections. France’s counterterrorism operation cost over $1 billion in 2020, and *a majority of French civilians oppose the French military presence in Mali. President Macron, whose political party faltered in municipal elections last March, will likely proceed with limited troop withdrawals as part of his reelection campaign.

A French intelligence official warned that al Qaeda seeks to expand its area of operations in West Africa. The head of France’s intelligence agency, Bernard Emie, *stated that al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its affiliates, including JNIM, will likely expand into the Gulf of Guinea in an interview on February 1. AQIM and JNIM leaders *met in February 2020 to discuss the expansion of AQIM operations beyond Mali. Emie warned that AQIM may use this expansion to *conduct attacks in Europe.

Forecast: JNIM will develop and gradually expand its governance apparatus in central Mali, where it will preserve its current area of operations and deepen its influence over local populations. JNIM will align with local populations to expand its access to resources. JNIM may recruit members from these populations. (Updated February 1, 2021)

Lake Chad

The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) deployed a rarely used explosive attack capability along the Nigeria-Niger border. ISWA claimed two suicide vehicle-born improvised explosive device (VBIED) attacks on Nigerian soldiers on January 10 and January 11. The group claimed to target Nigerian soldiers engaged in counterterrorism operations in northeastern Nigeria’s Borno state.[iv]

ISWA used VBIEDs in 2018, including an armored version. The group has billed its latest series of attacks as a counteroffensive against security forces.[v] ISWA is likely attempting to consolidate its positions along the Nigeria-Niger border.

Boko Haram’s leader threatened Nigeria’s new military commanders. Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari replaced the Nigerian army’s top commanders in an attempt to manage growing insecurity in northern and southern Nigeria on January 26. Boko Haram leader Abubakr Shekau responded to the reshuffling on January 27. Shekau boasted that the new commanders will fail to defeat Boko Haram as did their predecessors.[vi]

North Africa

Libya

Libya is at a pivotal moment in the UN-led transition process. The UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) announced a list of candidates for the presidential council and prime minister positions that will oversee the December 2021 elections. Candidates include Government of National Accord (GNA) Minister of Defense Salah al Din Nimroush, GNA Minister of Interior Fathi Bashagha, and the head of the east Libya–based parliament, Aguila Saleh. UNSMIL is convening a meeting of Libyan representatives to vote for the candidates from February 1 to February 5.

Foreign forces remain likely spoilers to a political resolution in Libya. UN Secretary General António Guterres urged foreign fighters to leave Libya by January 23 in cooperation with the UN’s October cease-fire and ongoing peace process. Foreign forces remain present, however, and are growing increasingly entrenched in the country. The internationally recognized GNA is partnering with Turkey for military training. The Wagner Group, a Russian private military company closely linked to the Kremlin, supports the Libyan National Army (LNA) and is building a large network of defensive positions in central Libya between Sirte and al Jufra air base, signaling Wagner’s intent to sustain its presence.

Forecast: Foreign militaries will deepen their footholds in Libya while jockeying for their preferred candidates to emerge as transitional leaders. Fighting between rival factions—whether between the GNA and LNA or within either coalition—will likely resume in the coming months. Renewed fighting would lift pressure from Salafi-jihadi militants in southwestern Libya and could create opportunities for the Islamic State to emerge from its current dormant status.

The current political process also creates an incentive for the Islamic State to attack if it retains the capability. The Islamic State in Libya has previously targeted state ministries in Tripoli during periods of potential progress as part of a larger effort to prevent the formation of a functional Libyan state. (Updated February 1, 2021)

[i] “Shabaab Claims Killing Western Officer, 4 Somali Special Forces in Blast Near Baledogle Airfield,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 18, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[ii] “Shabaab Claims Killing Western Officer, 4 Somali Special Forces in Blast Near Baledogle Airfield,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 18, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[iii] “In Formal Statement, Shabaab Identifies Former Top Somali General as Primary Target in Afrik Hotel Raid,” SITE Intelligence Group, February 1, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[iv] “ISWAP Claims Suicide Bombing Amid Flurry of Military Activity in Borno and Yobe States,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 11, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[v] “ISWAP Claims Killing at Least 20 in Counter-Offensive in Borno, Reports Attack in Diffa,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 18, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[vi] “Boko Haram Leader Shekau Derides New Military Chiefs Appointed by Nigerian President,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 28, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.