Africa File: The Islamic State comes to Mozambique

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

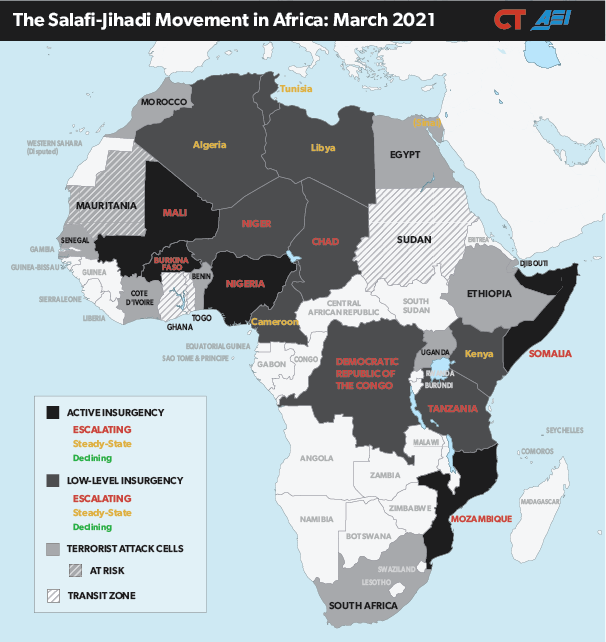

The global Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is spreading in Africa. An Islamic State–linked group in northern Mozambique is the latest case of a Salafi-jihadi group co-opting and expanding a local conflict. This insurgency, like those in Mali and Somalia, promises to spread into neighboring countries and deliver an enduring haven to extremist militants with regional and global ambitions while exacting a steep humanitarian toll.

Salafi-jihadi threats embedded in local conflicts are already plaguing several of Africa’s largest populations and economies. Algeria, Egypt, Kenya, and Nigeria face insurgencies within or across their borders. The Salafi-jihadi insurgency in northern Mozambique risks adding two significant economies—South Africa and Tanzania—to this list of vulnerable countries.

Read the report.

In this Africa File:

- Lake Chad. The destabilization of northeastern Nigeria has led to an uptick in mass kidnappings of schoolchildren. Islamic State militants in Nigeria targeted security forces and aid workers.

- Sahel. An Islamic State affiliate disrupted presidential elections in western Niger.

- Somalia. Al Shabaab doubled attacks in the capital since January amid political unrest.

- Kenya. Al Shabaab is exerting increasing social control in parts of northeastern Kenya.

- Ethiopia. Fighting is ongoing in the Tigray region in northeastern Ethiopia. A related border dispute has also raised tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan.

- Libya. Delays and accusations signal danger for the new Libyan transitional government.

Latest publications:

- Mozambique. Emily Estelle and Jessica Trisko Darden published an assessment of the Islamic State–linked insurgency in Mozambique, including a forecast and recommended policy response. Read the report here, and view the interactive graphic here.

- Ethiopia. CTP is publishing updates on the Ethiopia crisis. Sign up to receive the latest updates by email here. Read Jessica Kocan’s latest update here and Emily Estelle’s background on the conflict here.

Read Further On:

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: March 2021

Source: Emily Estelle.

Overview: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated March 3, 2021

The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is active across northern, eastern, and western Africa and is expanding and deepening its presence on the continent. This movement, like any insurgency, draws strength from access to vulnerable and aggrieved populations. Converging trends, including failing states and regional instability, are creating favorable conditions for the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion. Meanwhile, counterterrorism efforts rely on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding, and on states and local authorities that have demonstrated an inability to govern effectively.

West Africa. The Salafi-jihadi movement has spread rapidly in West Africa by exploiting ethnic grievances and state weaknesses that include human rights abuses, corruption, and ineffectiveness. An al Qaeda affiliate co-opted the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and has continued to expand southward through the Sahel region into central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. Sahel groups have not yet plotted attacks outside West Africa but have sought to drive Western security and economic presence out of the region while building lucrative smuggling and kidnapping-for-ransom enterprises. An al Qaeda–linked group in Mali is infiltrating governance structures, advancing an overarching Salafi-jihadi objective, and seeks to expand into Gulf of Guinea countries. West Africa has become an area of focus for transnational Salafi-jihadi organizations, with rival jihadists now fighting for dominance in the Sahel.

The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate is based in northwest Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—and conducts frequent attacks into neighboring states. Boko Haram and an al Qaeda–linked splinter group are also active in this region.

East Africa. Al Shabaab, an al Qaeda affiliate and the dominant Salafi-jihadi group in East Africa, is vocal about its intent to attack US interests and has begun to plot international terror attacks. The group enjoys de facto control over broad swathes of southern Somalia and can project power in the Somali federal capital Mogadishu and regional capitals where it regularly attacks senior officials. It seeks to delegitimize and replace the weak Somali Federal Government—a task made easier by endemic political dysfunction and corruption in Mogadishu. Al Shabaab’s governance ambitions extend to ethnic Somali populations in Kenya and Ethiopia.

Al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from eroding security conditions in East Africa. Ethiopia’s destabilization is already having regional effects, including weakening counter–al Shabaab efforts in Somalia. The drawing down of the US and African Union counterterrorism missions in Somalia will also reduce pressure on al Shabaab.

The Islamic State has also penetrated the region. Islamic State branches are now active in northern Somalia, the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Mozambique bordering Tanzania, where its affiliate seized a Mozambican port in August 2020 that it still controls. The Islamic State foothold in Mozambique marks the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion into southern Africa.

North Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups in North Africa are at a low point, but the fragility and grievances that led to their rise remain. The Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent security vacuums allowed Salafi-jihadi groups to organize and forge ties with desperate and coerced populations. The rise of the Islamic State brought a peak in Salafi-jihadi activity in North Africa, particularly from its branches in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Counterterrorism pressure has weakened Salafi-jihadi groups across North Africa in the past five years. The insurgencies in Libya and the Sinai are active but contained, and terrorist attacks across the region have decreased. Libya’s war will continue to create opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups, and severe instability or collapse in any North African state would likely bring the Salafi-jihadi threat back to the surface.

West Africa

Lake Chad

The destabilization of northeastern Nigeria has led to an uptick in mass kidnappings of schoolchildren. Gunmen kidnapped hundreds of schoolgirls in northwestern Nigeria’s Zamfara state on February 26. A similar incident occurred on February 17 at a boy’s school in western Nigeria’s Niger state.

The immediate and long-term causes of the kidnappings are ransom, insufficient security, and broader destabilization. *Family members of kidnappees reported receiving ransom demands, and the government likely paid or facilitated ransom payments despite official *denials. Nigerian authorities confirmed the release of the nearly 300 Zamfara state schoolgirls on March 2. Zamfara state officials claimed to offer amnesty and resettlement to the kidnappers in exchange for their surrender and the girls’ release.

The kidnappings are a reaction to insecurity in addition to poverty. Bandits negotiated with Nigerian officials for *greater government protection of civilians on February 27 in exchange for releasing the Niger state students. The bandits claimed that pro-government vigilante groups are the main cause of violence in local communities and asked the government to take greater measures to protect villagers from vigilantes. The bandits also complained about counterterrorism operations that destroyed homes and killed cattle.

Salafi-jihadi militants helped set the example of successful kidnapping for ransom and may also have facilitated recent kidnappings. Boko Haram has conducted several mass kidnappings in Nigeria, including the infamous Chibok girls kidnapping in 2014. More recently, the group claimed responsibility for kidnapping more than 300 students and demanded ransom in December 2020. Boko Haram allied with local bandit gangs to facilitate this kidnapping. Boko Haram is likely not responsible for the February kidnappings and has neither claimed the attacks nor mentioned them in recent *videos.[1]

Another possible link to Salafi-jihadi groups is Ahmad Gumi, a Nigerian Islamic scholar with an indirect link to Ansaru, an al Qaeda–linked group based in northwestern Nigeria. Gumi *facilitated recent negotiations with bandit groups, including the Niger state kidnappers. His involvement may indicate an Ansaru connection to either the kidnappings themselves or the negotiations in northwestern Nigeria.

The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) continued a trend of deploying more advanced explosive attack capabilities against security forces in northeastern Nigeria. ISWA conducted a suicide vehicle-born improvised explosive device (VBIED) attack on a Nigerian military *convoy in northeastern Nigeria’s Borno state on February 21, marking the group’s third VBIED attack since January and continuing an uptick in ISWA’s use of this tactic.[2] The operation and subsequent clashes killed 20 Nigerian soldiers. ISWA media released photos of seized vehicles, some of which will likely be used for future VBIED attacks.[3]

ISWA’s explosive attacks are part of the group’s greater campaign to consolidate its position in Borno state in northeastern Nigeria. The group has been conducting consistent attacks on security forces in Borno state and along the Nigeria-Niger border since January. ISWA recently *attacked a military vehicle carrying the Nigerian army’s counterinsurgency chief on February 28.

ISWA militants again attacked aid workers, likely to gain access to resources. ISWA militants attacked a UN base and a humanitarian hub, trapping 25 aid workers, in Dikwa in Borno state on March 1. The group launched *a second attack in the same location the following day after a Nigerian army *withdrawal. ISWA’s attack claim stated the group took control of the town and torched government and UN buildings in the process.[4] The UN is *evacuating aid workers from Borno state in response to the targeted attacks. The Islamic State designated humanitarian agencies as legitimate targets a few weeks after militants from ISWA’s Sahel branch captured and executed six French aid workers in August 2020. Aid workers tend to be unarmed and assist in transporting supplies to disadvantaged villages. Attacks on aid workers may be intended to gain resources and fit a trend toward increasingly brutal attacks on civilians and propaganda from Islamic State affiliates in West Africa.

Forecast: The rash of kidnappings in northern Nigeria will likely benefit Salafi-jihadi groups even if they are not directly involved. Deteriorating security will strain the state’s already limited resources. ISWA in particular, which has previously presented itself as an alternative security provider, may benefit as it consolidates its position in Borno State. ISWA militants will also continue attacking Nigerian security forces to gain supplies and deny freedom of movement to Nigerian forces in the northeast. (As of March 3, 2021)

Sahel

An Islamic State affiliate disrupted presidential elections in western Niger. An improvised explosive device (IED) attack killed seven electoral commission members and injured three others in western Niger’s Tillaberi region on February 21. The election officials were traveling to monitor the second round of Niger’s presidential elections. The IED may not have targeted these officials’ vehicle individually, but the location of the bombing and its timing indicate an intent to disrupt election administration.

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) is likely responsible for the attack. ISGS is present in western Niger and has been active in northern Tillaberi and in the Niger–Mali–Burkina Faso border region for several years. The group has conducted several attacks outside its traditional area of operations, including in southern Tillaberi near the February 21 attack location. These attacks aim to degrade local and national governance and influence civilian behavior in areas where state security forces are largely absent. ISGS frequently targets local leaders for cooperating with or assisting the Nigerien government. An ISGS attack killed more than 100 civilians in Tillaberi on January 2 during Niger’s first round of voting. Nigerien security forces *shut down some polling stations in Tillaberi’s villages due to the February 21 attack and other violent *incidents likely also related to ISGS.

The February 21 attack occurred as Niger held presidential elections marking the country’s first peaceful transition of power. Niger is a US security partner that faces several security challenges, including Salafi-jihadi insurgencies on its western and southeastern borders.

Nigerien security forces are violently suppressing Nigerien protestors after election results. Niger’s electoral commission declared Mohamed Bazoum, the ruling party candidate, the winner on February 23. Rival candidate Mahamane Ousmane accused the commission of election fraud and claimed he is the true victor. Pro-Ousmane protestors began violent demonstrations in the Nigerien capital, Niamey, for several days afterwards. Violent crackdowns by Nigerien security forces have led to over 400 arrests and at least two deaths. Attacks on election days throughout Niger may have affected results even if the officials conducted the election fairly.

Forecast: Broader political turmoil in Niger would worsen the security vacuum in the country’s west and create an opportunity for ISGS to be more aggressive in its efforts to coerce civilians and destroy local governance. Sustained unrest in Niger, should it occur, will give ISGS access to a more stable territorial base, strengthening the group and perhaps giving it an opportunity to recover from ongoing clashes with its rival, the al Qaeda–linked Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen based in neighboring Mali. (As of March 3, 2021)

East Africa

Somalia

Political and security trends in Somalia are lifting pressure from al Qaeda’s East African affiliate. The US troop withdrawal and drawdown of Ethiopian forces contributing to counterterrorism efforts in Somalia will reduce pressure on al Shabaab. The Somali Federal Government (SFG) simultaneously faces a constitutional crisis after failing to hold federal presidential elections on February 8, before the president’s mandate expired. The SFG has since been unable to reach an agreement with state officials over an electoral process.

Al Shabaab doubled attacks in the Somali capital since January. The group has concentrated attacks in central Mogadishu, primarily targeting security personnel. Al Shabaab claimed responsibility for 12 IED attacks targeting Somali National Army (SNA) positions in the capital on February 21.[5]

Al Shabaab also claimed responsibility for an IED attack targeting the SNA’s deputy commander in Hodan district on March 1. These attacks are part of al Shabaab’s ongoing campaign to destabilize and weaken the SFG. The SFG’s evolving constitutional crisis has created additional security concerns in the capital. SFG forces exchanged gunfire with protesters demonstrating against delayed elections in Mogadishu on February 19. The clash between SFG forces and civilians risks validating al Shabaab’s criticisms of the SFG’s failure to address Somali grievances, which the group portrayed in a documentary series in February.

Political turmoil threatens the cohesion of Somali security forces, though key forces have resisted pressure to enter the political fray so far. A former commander of US-trained Somali special forces (Danab) warned on February 19 that the Somali army is at risk of dissolving along clan lines and political affiliations. The SNA has struggled to create a national identity among members who often maintain loyalty to regional authorities rather than the SFG. The current Danab commander declined the SFG president’s request to deploy to Mogadishu, signaling the pressure that Somali commanders face to turn away from the counter–al Shabaab mission during the political crisis. Turkish-trained Somali police and SNA forces with an internal security focus have so far responded to recent protests in Mogadishu. The appearance of additional SNA units in the capital, particularly their redeployment away from active counter–al Shabaab operations elsewhere in Somalia, would indicate greater politicization in the SNA and growing military involvement in the country’s political crisis.

The SNA also heavily relies on external military support for its counterterrorism effort, namely from the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), which is meant to turn security responsibility to the SFG this year. The UN Security Council extended AMISOM’s mandate on February 25 for an additional two weeks to March 14.

Forecast: Al Shabaab will gain or regain territory in Somalia in the next two months as political unrest continues and counterterrorism efforts stall or falter. (As of March 3, 2021)

Kenya

Al Shabaab is exerting increasing social control in parts of northeastern Kenya. The group has taken over mosques, *intimidated local officials with violence, and targeted communication infrastructure to prevent security forces from responding to attacks since November 2020. Al Shabaab militants most recently *attacked a police station in neighboring Wajir County on February 21 and a Kenyan *soldier in Mandera County on February 27. The group is targeting security forces to increase its freedom of movement and deny protection to local populations.

Ethiopia

Ethiopian federal forces are fighting the Tigray People’s Liberation Front west of the Tigray regional capital. Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed claimed victory in Tigray when Ethiopian federal forces seized Mekelle, Tigray’s capital, in late November 2020. Fighting has continued since, however. Limited available information suggests fighting has been concentrated west of the capital at least since mid-February. Reports include intentional fires destroying civilian homes in Gijet and federal force air strikes in Samre, two towns roughly 35 miles southwest of Mekelle.

Media access in Tigray remains limited as the government pressures the few media personnel now active in the region. International bodies and foreign countries have pleaded with Prime Minister Abiy to allow media access to Tigray as reports of grave humanitarian abuses committed by Ethiopian and Eritrean troops continue to emerge. Abiy’s administration acknowledged that widespread rape occurred during the conflict on February 11. The Ethiopian government *granted restricted media access to seven international news outlets on February 24. The government warned journalists of “corrective measures” if they fail to adhere to its regulations. Ethiopian soldiers have already beaten and arrested two translators for foreign reporters on February 27 and arrested a BBC journalist in Mekelle on March 1. The Ethiopian government released the translators and reporter on March 3 without charges.

The UN Security Council meets to discuss Ethiopia on March 4.

Tensions between Sudanese and Ethiopian forces continue along the shared border. Friction between the two countries began in December 2020 when Sudanese troops took advantage of Ethiopia’s distraction with its Tigray conflict to reclaim disputed land in the Fashqa triangle. The border dispute escalated in mid-February when Sudan’s foreign minister accused Ethiopian forces of encroaching on Sudan’s land.

Ethiopia’s foreign minister similarly accused Sudanese troops of continuing to expand into Ethiopian territory. Ethiopian militiamen, known as shifta, *clashed with Sudanese farmers on February 25, seizing farmland and looting crops in the Fashqa triangle. Sudanese troops *claimed to regain control of agricultural land from shifta on February 28 and *have continued fighting with shifta as of March 3.

North Africa

Delays and accusations are disrupting the Libyan peace process. A UN-facilitated forum appointed the heads of a new transitional government in February. The new prime minister, Abdulhamid Dbeibeh, has not yet named his cabinet despite a February 26 deadline. Accusations of vote-buying and bribing supporters have also marred the process.

A disputed attack on a senior official is an indicator of potential unrest in western Libya. Fathi Bashagha, the interior minister of the former transitional government, was a favored but ultimately losing candidate for a leading position in the new interim government. He accused a Tripoli-based security force of attacking his convoy on February 21. The attacking militia confirmed its involvement in the attack but said in an online statement that Bashagha’s guards *initiated the altercation. A Tripoli-based prosecutor responsible for investigating the event, stated the attack was not an assassination attempt, contrary to Bashagha’s *claims, and ordered the detention of Bashagha’s bodyguards. Bashagha is a key figure in western Libyan security and has made allies and enemies among the regions’ complex web of militias in recent years. The shift to the new transitional government is a potential flash point for the uneasy balance of power in Tripoli and its environs.

Forecast: Libyan militias and foreign militaries will attempt to exert influence through the interim government but may revert to violence should they assess they cannot secure their interests through political channels. Renewed fighting in Tripoli would likely be short-lived, particularly given Turkish military support for certain factions. Internecine fighting in the west could open an opportunity for national rivals to reactivate military campaigns in Libya’s center or south, however, raising the risk of renewed civil war.

Renewed fighting would lift pressure from Salafi-jihadi militants in southwestern Libya and could create opportunities for the Islamic State to emerge from its current dormant status. The current political process also creates an incentive for the Islamic State to attack if it retains the capability. The Islamic State in Libya has targeted state ministries in Tripoli during periods of potential progress as part of a larger effort to prevent the formation of a functional Libyan state. (Updated March 3, 2021)

[1] “Boko Haram Leader Announces Responsibility for Abducted Hundreds of Schoolboys in Katsina,” SITE Intelligence Group, December 15, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[2] “'Amaq Video Shows ISWAP Fighter Involved in SVBIED Operation Near Goniri, Clash with Nigerian Troops,” SITE Intelligence Group, February 22, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[3] “ISWAP Gives Photo Documentation of Aftermath of Multiple Attacks on Nigerian Troops in Borno,” SITE Intelligence Group, March 2, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[4] "ISWAP Claims Taking Control Over 2 Towns in Northeast Nigeria, Torching Government and UN Buildings,” SITE Intelligence Group, March 3, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[5] “Shabaab Claims Wave of 12 Bombings on Multiple SNA Positions in Capital,” SITE Intelligence Group, February 23, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.