Africa File: Islamic State overruns northern Mozambique port

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

An Islamic State affiliate dramatically escalated its campaign in Mozambique last week, overrunning Palma in the country’s far north. The takeover gives Salafi-jihadi militants control of a second port and has intensified the country’s already dire humanitarian crisis. The attack’s targets included foreign personnel of a nearby liquefied natural gas project.

Islamic State militants are on track to gain a permanent foothold on Africa’s eastern coastline. Mozambique’s military lacks the capability and man power to wage an effective counterinsurgency campaign in the remote region bordering Tanzania. Recently announced US and Portuguese efforts to train partner forces in Mozambique will not have a significant effect given these structural weaknesses.

Salafi-jihadi militants are also gaining ground in the Sahel region in West Africa. An Islamic State affiliate has resumed a campaign of high-profile attacks targeting civilians and security forces in Mali and western Niger. This group is poised to capitalize should political unrest destabilize Niger, which suffered a coup attempt on March 31.

Meanwhile, al Qaeda’s Sahel branch is expanding southward into coastal states on the Gulf of Guinea and Atlantic coasts. Militants can now conduct raids from bases in Burkina Faso into Côte d’Ivoire, underscoring Burkina Faso’s rapid deterioration. Burkina Faso was among the most secure countries in this region until 2017, but a Salafi-jihadi insurgency has since displaced more than one million people.

In this Africa File:

- Mozambique. Islamic State–linked militants conducted a coordinated attack to seize a second port in northern Mozambique.

- Somalia. Al Shabaab is seeking to expand its area of influence in southwestern Somalia. It also targeted Somali government election talks and called for attacks in Djibouti.

- Ethiopia. Eritrean troops will remain in Tigray region despite international pressure. Tensions between Ethiopia and Egypt are rising over Ethiopia’s Nile dam.

- Sahel. Islamic State militants resumed regular large-scale attacks on civilian targets in Niger, which also faces political unrest following an attempted coup. Al Qaeda’s Sahel affiliate is expanding into coastal West African states.

- Libya. The Libyan National Army coalition is fragmenting in Benghazi, creating conditions that may favor the reemergence of Salafi-jihadi groups.

Latest publications:

- Mozambique. Emily Estelle discussed the Islamic State in Mozambique on BBC World News. Watch here, or listen to a recent radio interview here. Estelle and Jessica Trisko Darden recently published a report on Mozambique, including a forecast and recommended policy response. Read the report here, and view the interactive graphic here.

- Ethiopia. CTP is publishing updates on the Ethiopia crisis. Sign up to receive the latest updates by email here. Read Jessica Kocan’s latest update here and Emily Estelle’s background on the conflict here.

Read Further On:

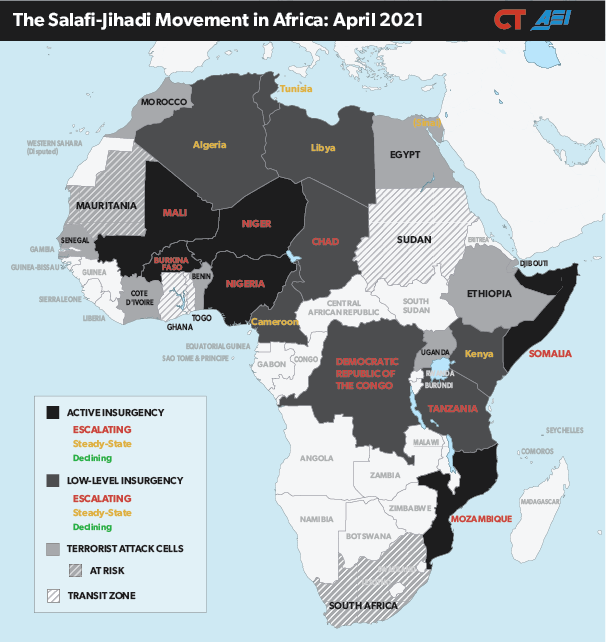

Figure 1. The Salafi-jihadi Movement in Africa: April 2021

Source: Emily Estelle.

Overview: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated April 1, 2021

The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is active across northern, eastern, and western Africa and is expanding and deepening its presence on the continent. This movement, like any insurgency, draws strength from access to vulnerable and aggrieved populations. Converging trends, including failing states and regional instability, are creating favorable conditions for the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion. Meanwhile, counterterrorism efforts rely on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding, and on states and local authorities that have demonstrated an inability to govern effectively.

West Africa. The Salafi-jihadi movement has spread rapidly in West Africa by exploiting ethnic grievances and state weaknesses that include human rights abuses, corruption, and ineffectiveness. An al Qaeda affiliate co-opted the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and has continued to expand southward through the Sahel region into central Mali and the peripheries of Burkina Faso. An Islamic State–linked group is active in the same area, particularly western Niger. Sahel groups have not yet plotted attacks outside West Africa but have sought to drive Western security and economic presence out of the region while building lucrative smuggling and kidnapping-for-ransom enterprises. An al Qaeda–linked group in Mali is infiltrating governance structures, advancing an overarching Salafi-jihadi objective, and expanding into Gulf of Guinea countries. West Africa has become an area of focus for transnational Salafi-jihadi organizations, with rival jihadists now fighting for dominance in the Sahel.

The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate is based in northwest Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—and conducts frequent attacks into neighboring Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Boko Haram and an al Qaeda–linked splinter group are also active in this region.

East Africa. Al Shabaab, an al Qaeda affiliate and the dominant Salafi-jihadi group in East Africa, is vocal about its intent to attack US interests and has begun to plot international terror attacks. The group enjoys de facto control over broad swathes of southern Somalia and can project power in the Somali federal capital Mogadishu and regional capitals where it regularly attacks senior officials. It seeks to delegitimize and replace the weak Somali Federal Government (SFG)—a task made easier by endemic political dysfunction and corruption in Mogadishu. Al Shabaab’s governance ambitions extend to ethnic Somali populations in Kenya and Ethiopia, and the group conducts regular attacks in eastern Kenya.

Al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from eroding security conditions in East Africa. Ethiopia’s destabilization is already having regional effects, including weakening counter–al Shabaab efforts in Somalia. The drawing down of the US and African Union counterterrorism missions in Somalia will also reduce pressure on al Shabaab.

The Islamic State has also penetrated the region. Islamic State branches are now active in northern Somalia, the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Mozambique, bordering Tanzania, where its affiliate seized a second Mozambican port in March 2021. The Islamic State foothold in Mozambique marks the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion into southern Africa.

North Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups in North Africa are at a low point, but the fragility and grievances that led to their rise remain. The Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent security vacuums allowed Salafi-jihadi groups to organize and forge ties with desperate and coerced populations. The rise of the Islamic State brought a peak in Salafi-jihadi activity in North Africa, particularly from its branches in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Counterterrorism pressure has weakened Salafi-jihadi groups across North Africa in the past five years. The insurgencies in Libya and the Sinai are active but contained, and terrorist attacks across the region have decreased. Libya’s political and security crisis will continue to create opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups, and severe instability or collapse in any North African state would likely bring the Salafi-jihadi threat back to the surface.

East Africa

Mozambique

The Islamic State in Mozambique (IS-M)[i] conducted a coordinated attack to seize a second port in northern Mozambique. IS-M militants overran Palma, a port city in the far north of Cabo Delgado province near the Tanzanian border. Palma is 50 miles north of Mocimboa da Praia, a port that IS-M seized in August 2020.

The attack on Palma demonstrated a new degree of sophisticated attack planning for IS-M, likely includingpreparations throughout the rainy season in the first three months of 2021. IS-M members gradually infiltratedweapons into the city in backpacks and embedded themselves among community members by wearing military and police uniforms. The group launched the attack in Palma on March 24 with roughly 120 militants. A similarly sized reinforcement arrived the next day. The total attacking force is a large proportion of the group’s estimated 1,000 militants, indicating the attack’s importance to IS-M. The militants targeted a local police station and a military base, likely to hinder the security forces’ response and possibly to seize additional ammunition and weapons. IS-M militants based in neighboring Tanzania also crossed the border into Mozambique to support fighters on March 25. Islamic State media officially declared IS-M’s control of Palma on March 29.[ii] The use of old photos in Islamic State media indicates ongoing challenges with IS-M’s media capability.

IS-M retains control of Palma at time of publication. The Mozambican military has struggled to mount a response. Mozambican Special Forces launched an operation to recapture Palma on March 28 but failed. The head of Dyck Advisory Group, a South African private military contractor that has been involved in the counter–IS-M fight and that worked to evacuate civilians from Palma during the attack, said that Mozambican forces did not join the fight for several days.

Palma presents IS-M with several strategic benefits. Access to the sea will increase the group’s access to food, which has become limited in Cabo Delgado during the conflict. IS-M targeted food trucks during the Palma attack, beheading drivers. Palma’s location 50 miles south of the Tanzanian border may also reflect efforts to strengthen IS-M’s operations in the border region. IS-M has many Tanzanian members and conducted its first cross-border attack into Tanzania in October 2020.

The Palma attack is also a major blow to foreign investment in Mozambique’s hydrocarbon industry. French oil and gas company Total manages a logistical center about five miles from Palma to support its multibillion-dollar gas project on the Afungi peninsula. Total has evacuated about 1,000 workers since the attack, which caused dozens of foreign casualties.

The Palma attack also worsens the already severe humanitarian crisis in northern Mozambique. The attack killeddozens of locals and foreigners, though the exact number of casualties remains unknown, and displaced more than 8,000. The World Food Programme is working to assist 50,000 people affected by the fighting in Palma, which was home to roughly 70,000 residents. Some residents have fled to Mueda, about 110 miles south of Palma, and others to Pemba. However, approximately 6,000 to 10,000 people were waiting to be evacuated from Palma and Afungi as of March 30. The insurgency has displaced approximately 670,000 people to date since IS-M began staging attacks in Cabo Delgado province in 2017.

Forecast: Mozambique’s military will struggle to recapture Palma as it has Mocimboa da Praia. The Palma takeover further limits Mozambican military access to Cabo Delgado province, and moving troops to the area will pose a huge logistical challenge. The Mozambican military’s small size also reduces its ability to conduct effective counterinsurgency. Clearing the city will be particularly difficult as militants hide in civilian homes. (As of April 1, 2021)

Somalia

Political and security trends in Somalia are lifting pressure from al Qaeda’s East African affiliate. The US troop withdrawal and drawdown of Ethiopian forces contributing to counterterrorism efforts in Somalia will reduce pressure on al Shabaab. The Somali Federal Government (SFG) simultaneously faces a constitutional crisis after failing to hold federal presidential elections on February 8, before the president’s mandate expired.

Al Shabaab continues to target the SFG’s electoral negotiations but is not the primary cause of the delayed agreement. The SFG failed to hold presidential elections over disagreements with Somali federal states on the electoral process. Several *political issues are disrupting negotiations between the SFG and the Jubbaland and Puntland State presidents. Al Shabaab has attempted to further delay electoral meetings by threatening security at meeting locations. The group targeted Halane base camp, the proposed meeting location between the SFG and member states in the Somali capital of Mogadishu, in early March. The group most recently *fired mortars toward Halane on March 25. The SFG *held a meeting with state representatives at Halane on March 29 despite the al Shabaab threat.

Al Shabaab is seeking control over agricultural supply routes by expanding its area of influence in southwestern Somalia. Al Shabaab *prevented commercial vehicles from entering Jowhar, the administrative capital of Middle Shabelle region, in mid-February. Al Shabaab levies taxes on businesses and vehicles operating in the city, which is nominally controlled by Somalia’s Hirshabelle State. Al Shabaab is likely attempting to control a road that links Jowhar to Mahaday town, 16 miles north of Jowhar. Mahaday is an agricultural town with multiple roads used to transport crops to surrounding villages. Al Shabaab *attempted an attack on a Somali National Army (SNA) base in Mahaday town on March 15 and claimed to capture the town. The SNA claimed to repulse the attack, but residents said al Shabaab retains control of neighboring villages. The group attacked a Burundian African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) base near Mahaday on *March 21 and *April 1.

Forecast: Al Shabaab will attempt another advance on Mahaday town to gain control of the local trade and economy in the southern Middle Shabelle region. Al Shabaab briefly *seized Mahaday in 2016 before AMISOM forces drove the militants out of the town. (As of April 1, 2021)

Al Shabaab threatened attacks on US interests in Djibouti. Al Shabaab’s leader, Ahmad Umar, *called on Djiboutian citizens to target French and American interests in the country and to conduct lone-wolf attacks on March 27.[iii] Al Shabaab will likely be unable to conduct large-scale attacks in Djibouti, however. Al Shabaab’s activity in Djibouti has historically been limited. The group deployed two suicide bombers to a restaurant in the Djiboutian capital in May 2014. The attack targeted French soldiers, injuring several soldiers and killing one Turkish national. The group has not conducted any significant attacks in Djibouti since, likely in part due to improved security measures.

The US and France are among the countries with significant military bases in Djibouti. US Africa Command’s Combined Joint Task Force–Horn of Africa trains Djiboutian soldiers and most recently engaged with Djibouti’s new signal battalion for the first time during a field training exercise from March 15 to March 18.

Ethiopia

Eritrean troops will remain in Tigray. Eritrean troops have been in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region since the conflict began in November 2020. Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed promised on March 26 that Eritrean forces would withdraw from Tigray, likely in response to pressure from the US and UN to address Eritrean troop abusesagainst civilians in Tigray.

Eritrean troops do not appear to be withdrawing from the region, however. Eritrean troops sent reinforcements into Ethiopia through a border town on March 27. Abiy and the Eritrean president reportedly agreed to integrate Eritrean forces into the Ethiopian military. If true, this agreement signals Abiy’s intent to preserve Eritrean forces’ presence in Ethiopia while obscuring it from international observers.

Tensions between Ethiopia and Egypt over distribution of the Nile River’s water supply are rising. Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al Sisi said on March 30 that Egypt’s share of the Nile River is “untouchable,” a warning to Abiy’s administration, which plans to begin its second filling of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam this July. Ethiopia’s unilateral decision has caused Sudan and Egypt to call for international mediation in the ongoing dispute. A military confrontation is possible should Cairo perceive an existential threat to its water supply that cannot be resolved through negotiations. Such a conflict would draw in Sudan and destabilize eastern Africa while layering another threat to Ethiopia’s stability and cohesion.

West Africa

Sahel

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) resumed regular large-scale attacks on security and civilian targets in Mali and Niger. ISGS militants attacked villages in western Niger, killing 137 civilians, on March 21. The militants also claimed an attack that killed 22 Malian soldiers on the same day.

The recent spate of attacks indicates that ISGS has regained attack capability after a decrease in attacks in late 2020 due to clashes with rival Salafi-jihadis and pressure from counterterrorism forces. ISGS began clashing with al Qaeda–linked Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) in late 2019 and fighting has continued since. JNIM expelled ISGS from Mali’s southern border in September 2020. French-led Operation Barkhane *focused its operations on ISGS throughout 2020, further weakening ISGS, before shifting its focus toward JNIM in October 2020.

ISGS responded to pressure by increasing its activity in western Niger’s Tillaberi region, where a security vacuum and ethnic tensions have allowed the group to operate for years. JNIM is not competing for a presence in Tillaberi, giving ISGS the opportunity to regroup without a threatening competitor. ISGS gained resources by collecting zakat (religious tax) and participating in cattle raiding and pillaging villages throughout western Niger.

ISGS may also benefit from growing ties to the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA), the Islamic State’s affiliate operating in Lake Chad. ISWA may have provided ISGS with reinforcements to conduct the March 21 attack in Niger. (ISGS is formally part of ISWA under the Islamic State’s organization, but ISGS and the Lake Chad ISWA branch function as separate organizations.)

ISGS is targeting civilians and security forces to deepen its presence near the Niger-Mali border. ISGS killed 58 civilians returning from a livestock market in Tillaberi on March 15. ISGS has exploited ethnic tensions to ally with several ethnic groups in Niger and established a support zone in the region. The group has been conducting attacks against civilians of the Fulani ethnic group to obtain resources. A JNIM subgroup has historically recruited from aggrieved Fulani communities and presented itself as a defender of the Fulani community. JNIM quickly deniedresponsibility for the March 21 attack and denounced the targeting of civilians. JNIM presents itself as more lenient than ISGS by eschewing large-scale attacks on civilians.

ISGS militants also ambushed Malian soldiers in southern Mali’s Tessit region on March 15, killing 33 soldiers. The group also claimed an attack on Malian soldiers in Tessit less than a week later on March 21. These attacks indicate that ISGS has established a reliable support zone in Niger from which it can repeatedly attack into Mali.

A coup attempt indicates that Niger is at-risk for a political crisis, which could destabilize the country and provide greater opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups already active there. A Nigerien military unit attempted to seize the Nigerien capital, Niamey, and the presidential palace on March 31. Nigerien security forces arrested the soldiers involved in the coup and claimed the situation is under control.

President-elect Mohamad Bazoum will be sworn into office on April 2, marking Niger’s first democratic transition of power. ISGS extended its area of operations into areas previously considered safe near Niamey in 2020 and would likely seek to exacerbate unrest by attacking in the capital region.

Al Qaeda’s Sahel affiliate is expanding into littoral West Africa. About 60 heavily armed militants attacked an army post in northeastern Côte d’Ivoire’s Kafolo town on March 29, killing at least two Ivorian soldiers. This is the *third attack on Kafolo in less than a year. Al Qaeda–linked JNIM is likely responsible for this attack.

The militants’ ability to attack across the border and retreat into Burkina Faso underscores the high level of freedom of movement that Salafi-jihadi militants enjoy in the country’s perimeter. Burkina Faso was among the most secure countries in this region until 2017. Violence largely perpetrated by Salafi-jihadi groups has since displaced more than one million people.

Recent al Qaeda–linked attacks into Côte d’Ivoire reflect a shift in tactics and intent from prior attacks, notably a high-profile al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) attack on a resort in the Ivorian capital Abidjan in March 2016. This attack targeted a location frequented by Westerners in a bid to remove Western presence from West Africa and to punish Côte d’Ivoire for contributing troops to the UN mission in Mali. JNIM’s recent cross-border attacks into Côte d’Ivoire reflect an effort to expand its support zones beyond its traditional area of operations.

The Côte d’Ivoire attack is the latest example of JNIM’s efforts to expand into West African coastal states. Beninese rangers countered a JNIM operation in northwestern Benin on March 25. The militants had entered Benin from Burkina Faso. Similarly, Senegalese security forces *dismantled a JNIM cell near the Senegal-Mali border in January 2021.

AQIM and JNIM leaders *met in February 2020 to discuss the expansion of al Qaeda’s operations beyond Mali to establish a greater foothold in West Africa. Pro–al Qaeda media has begun to emphasize the group’s expansion, releasing a map in December 2020 and again on March 1 that indicated the group’s presence in Côte d’Ivoire compared to a prior map displaying the group only in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger months before.[iv] Access to West Africa’s Atlantic coast creates opportunities for al Qaeda and its affiliates to exploit transportation and communication lines that may aid the group in future attacks.

Forecast: JNIM will likely continue conducting sporadic, small-scale attacks in Mali’s bordering countries, including Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, to deter security forces and increase freedom of movement in border regions. (As of April 1, 2021)

North Africa

Libya

An uptick in violence in Benghazi indicates that the Libyan National Army (LNA) coalition is fragmenting. Violence is increasing in Benghazi, the largest city in LNA-controlled eastern Libya, coinciding with the installation of Libya’s new interim government, the Government of National Unity (GNU). The LNA is a militia coalition under the leadership of Khalifa Haftar. Haftar’s power has lessened since mid-2020 when his forces withdrew from western Libya after a failed attempt to unset the GNU’s predecessor.

Rising violence in Benghazi reflects conflict between factions aligned or previously controlled by the LNA to varying degrees. Factions that have supported the LNA, including tribes, are pushing back against elements of the LNA that have overstepped.

Benghazi civilians called on the LNA to investigate extrajudicial killings on March 15, including the death of Hanan Barasi from November 2020. Barasi was an activist and lawyer who openly criticized the LNA and Haftar. These calls for accountability came as tribes that had historically supported the LNA announced their support for the GNU on March 17.

Tribal leaders also called on the GNU to conduct an investigation after Benghazi police *discovered eight bodies with headshot wounds on March 18. The LNA’s Saiqa Brigade, led by Mahmoud al Werfalli, is likely responsible for these killings. Werfalli carried out similar execution-style killings against detainees in eastern Libya and was wanted by the International Criminal Court for committing war crimes, including executing prisoners of war.

Unidentified gunmen assassinated Werfalli in Benghazi on March 24 less than a week after Benghazi police discovered the bodies. Benghazi police *arrested two suspects in connection with Werfalli’s assassination, including Hanan al Barasi’s *daughter, less than a day after the assassination, indicating that the suspects may be scapegoats.

LNA commander Khalifa Haftar’s son, Saddam Haftar, may be responsible for Werfalli’s death, indicating infighting within the LNA coalition. Members of Werfalli’s tribe have accused the LNA General Command of assassinating Werfalli. The gunmen may have assassinated Werfalli to regain support from local tribal leaders and other LNA commanders who opposed Werfalli.

Inter-militia violence will likely reshape the political and security situation in eastern Libya. Werfalli commanded a loyal group of thousands of fighters that will likely escalate attacks in retaliation for his death. The Saiqa Brigade stressed its loyalty to Haftar in its statement mourning Werfalli’s death. However, the brigade may conduct retaliatory attacks against tribal leaders or other brigades that opposed Werfalli.

Werfalli’s assassination and the escalating violence in Benghazi will likely continue to fragment the LNA and its supporters, as well as eastern tribes. This fragmentation will likely cause a security vacuum because the GNU lacks the forces required to extend security to Benghazi. Militias on the ground will likely continue their operations even if the GNU attempt to de-escalate the situation on a political level.

The newly installed GNU faces other security challenges, including deteriorating security in Libya’s capital. Violence and assassinations have increased in Tripoli since the GNU took office, including clashes between several Tripoli militias that had been loosely affiliated with the GNU’s predecessor, the Government of National Accord.

The destabilization of Benghazi will create conditions for latent Salafi-jihadi networks to resume activity in the city. The LNA fought a prolonged battle to oust Al Qaeda– and Islamic State–linked groups from Benghazi in 2016–17. The destabilization of Benghazi would allow Salafi-jihadi militants to emerge from their current dormant state and reestablish footholds in the seams of the renewed conflict. Salafi-jihadi groups have previously made common cause with other militias, including against the LNA, and may reprise this strategy should conflict break out in Benghazi. Militants based elsewhere in Libya, notably the southwest, may also seek to return to coastal Libya by establishing cells in the east under cover of unrest.

[i] This insurgent group goes by many names, and the group itself has not declared one. CTP refers to the group as the Islamic State in Mozambique (IS-M). This choice should not be taken as an overstatement of the group’s relationship to Islamic State leadership nor as a dismissal of the complications inherent in assessing a group’s ideology, composition, or affiliations. For more on naming, see page 5 in the report, “Combating the Islamic State’s Spread in Africa: Assessment and Recommendations for Mozambique,” https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/combating-the-islamic-states-spread-in-africa-assessment-and-recommendations-for-mozambique.

[ii] “IS Formally Announces Control Over Mozambican City of Palma, Killing Over 55 Including Foreign Nationals,” SITE Intelligence Group, March 29, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[iii] “Shabaab leader labels Djibouti ‘Center of Enemy Plots,’ Calls to Attack American and French Interests,” SITE Intelligence Group, March 27, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[iv] “Pro-AQ Media Unit Follows-up on Alleged JNIM Projectile Attacks on French-EU Bases, Gives Map of Fighter Presence,” SITE Intelligence Group, December 1, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.