Africa File: Islamic State withdraws from northern Mozambique town, but challenges remain

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

An Islamic State affiliate relinquished control of Palma in northern Mozambique after inflicting dozens of casualties, displacing thousands, and looting money and supplies. While Mozambican security forces have returned to Palma, they lack the capability to secure the area or recapture significant terrain from the militants, who have held another coastal town since August 2020. The Palma attack marks a step change for the Mozambique insurgency but it is not an anomaly for Sub-Saharan Africa, where Salafi-jihadi groups are on the offensive in multiple countries.

In this Africa File:

- Mozambique. Islamic State–linked militants withdrew from Palma in Mozambique’s far north after more than a week, but subsequent attacks are likely. Mozambique’s military faces several challenges that will prevent it from recapturing significant terrain.

- Somalia. Al Shabaab is attacking bases in areas surrounding Somalia’s capital to increase its freedom of movement on key roads. Somalia’s political crisis is ongoing and unlikely to end following a controversial two-year extension of the president’s mandate.

- Ethiopia. Fighting is ongoing in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region and Eritrean troops remain present. Tensions are high between Ethiopia and both Sudan and Egypt.

- Libya. The Libyan National Army commander and his external backers launched an effort to gain popular support before Libyan elections in December 2021.

- Sahel. Al Qaeda’s Mali affiliate attempted a large attack on a UN base in northern Mali. A peace agreement between Salafi-jihadi militants and ethnic-based militias may be breaking down in central Mali.

- Lake Chad. The Islamic State’s West Africa Province is attacking aid workers to seize resources while sustaining operations on multiple fronts.

Latest publications:

- Mozambique. Emily Estelle discussed the Islamic State in Mozambique on BBC World News. Watch here, or listen to a recent radio interview here. Estelle and Jessica Trisko Darden recently published a report on Mozambique, including a forecast and recommended policy response. Read the report here, and view the interactive graphic here.

Read Further On:

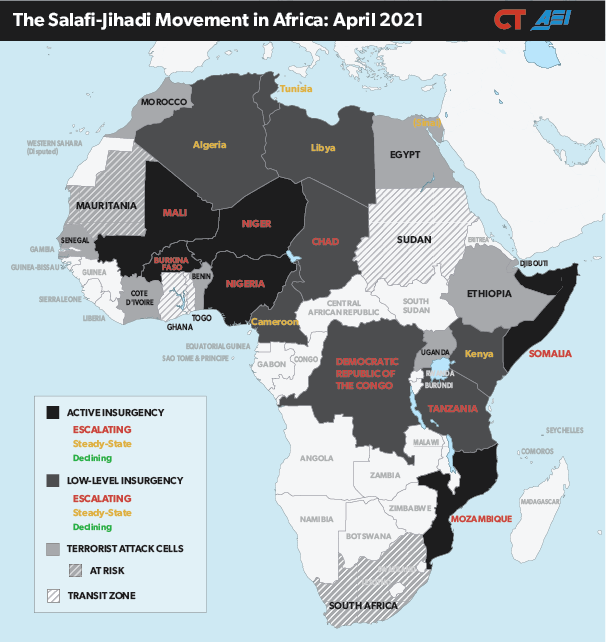

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: April 2021

Source: Authors.

Overview: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated April 1, 2021

The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is active across northern, eastern, and western Africa and is expanding and deepening its presence on the continent. This movement, like any insurgency, draws strength from access to vulnerable and aggrieved populations. Converging trends, including failing states and regional instability, are creating favorable conditions for the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion. Meanwhile, counterterrorism efforts rely on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding, and on states and local authorities that have demonstrated an inability to govern effectively.

West Africa. The Salafi-jihadi movement has spread rapidly in West Africa by exploiting ethnic grievances and state weaknesses that include human rights abuses, corruption, and ineffectiveness. An al Qaeda affiliate co-opted the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and has continued to expand southward through the Sahel region into central Mali and the peripheries of Burkina Faso. An Islamic State–linked group is active in the same area, particularly western Niger. Sahel groups have not yet plotted attacks outside West Africa but have sought to drive Western security and economic presence out of the region while building lucrative smuggling and kidnapping-for-ransom enterprises. An al Qaeda–linked group in Mali is infiltrating governance structures, advancing an overarching Salafi-jihadi objective, and expanding into Gulf of Guinea countries. West Africa has become an area of focus for transnational Salafi-jihadi organizations, with rival jihadists now fighting for dominance in the Sahel.

The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate is based in northwest Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—and conducts frequent attacks into neighboring Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Boko Haram and an al Qaeda–linked splinter group are also active in this region.

East Africa. Al Shabaab, an al Qaeda affiliate and the dominant Salafi-jihadi group in East Africa, is vocal about its intent to attack US interests and has begun to plot international terror attacks. The group enjoys de facto control over broad swathes of southern Somalia and can project power in the Somali federal capital Mogadishu and regional capitals, where it regularly attacks senior officials. It seeks to delegitimize and replace the weak Somali Federal Government (SFG)—a task made easier by endemic political dysfunction and corruption in Mogadishu. Al Shabaab’s governance ambitions extend to ethnic Somali populations in Kenya and Ethiopia, and the group conducts regular attacks in eastern Kenya.

Al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from eroding security conditions in East Africa. Ethiopia’s destabilization is already having regional effects, including weakening counter–al Shabaab efforts in Somalia. The drawing down of the US and African Union counterterrorism missions in Somalia will also reduce pressure on al Shabaab.

The Islamic State has also penetrated the region. Islamic State branches are now active in northern Somalia, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Mozambique, bordering Tanzania, where its affiliate seized a second Mozambican port in March 2021. The Islamic State foothold in Mozambique marks the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion into southern Africa.

North Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups in North Africa are at a low point, but the fragility and grievances that led to their rise remain. The Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent security vacuums allowed Salafi-jihadi groups to organize and forge ties with desperate and coerced populations. The Islamic State’s rise brought a peak in Salafi-jihadi activity in North Africa, particularly from its branches in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Counterterrorism pressure has weakened Salafi-jihadi groups across North Africa in the past five years. The insurgencies in Libya and the Sinai are active but contained, and terrorist attacks across the region have decreased. Libya’s political and security crisis will continue to create opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups, and severe instability or collapse in any North African state would likely bring the Salafi-jihadi threat back to the surface.

East Africa

Mozambique

The Islamic State in Mozambique (IS-M)[i] temporarily withdrew from Palma but retains a position of strength in northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province. IS-M overran Palma from March 24 to April 2, displacing more than 14,500 people from the town and tens of thousands more in Palma district. This civilian displacement adds to the more than 700,000 people already displaced from Cabo Delgado province due to fighting since 2017. Militants killed at least 87 people, including about a dozen foreigners, during the Palma attack, and approximately 20,000 people remain missing. The attack also disrupted a multibillion-dollar offshore liquified natural gas project run by the French company Total.

Mozambican security forces launched a failed operation to recapture Palma on March 28. They then claimed to regain control of Palma on April 4, after militants withdrew from the city to the surrounding bush. Total’s contractors accused Mozambican police and soldiers of looting facilities in Palma following the militants’ withdrawal.

Mozambique’s military is ill prepared to counter IS-M. The Mozambican security forces’ vulnerabilities include a lack of weapons training. A disruption in air support will also hinder operations in northern Mozambique. A contract between Mozambique’s interior ministry and South African private military contractor Dyck’s Advisory Group (DAG) expired on April 6. DAG provided air support to Mozambican forces and worked to evacuate civilians during the Palma attack. Mozambique now *plans to provide its own air support through Mozambican pilots trained to fly helicopters by South African defense contractor Paramount, through a contract with Mozambique’s defense ministry.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC), an intergovernmental block of South African countries, *met in Mozambique’s capital from April 8 to 9 to discuss the Cabo Delgado crisis. Zimbabwe’s president said the group agreed to mobilize a SADC brigade to intervene in the conflict. The Mozambican government has not confirmed this discussion, however, and Mozambique’s president said on April 8 that Mozambique will not accept foreign support on certain issues over fears of compromising Mozambique’s sovereignty. The SADC agreed to meet again on April 29.

Forecast: IS-M militants will likely exploit DAG’s absence by targeting Mueda, a town housing the Mozambican military’s main base in Cabo Delgado province. DAG forces targeted militants between Mueda and Namacande in November 2020. IS-M has not yet attacked Mueda, but it ambushed a military vehicle traveling from Nangade town to Mueda in early March and attacked army posts near Mueda in mid-March. (As of April 14, 2021.)

Somalia

Al Shabaab is attacking bases in the Lower Shabelle region to increase its freedom of movement on the roads toward Somalia’s capital Mogadishu. Al Shabaab targets the SFG in Mogadishu in an ongoing campaign to weaken and destabilize the SFG, which faces an ongoing political crisis after failing to hold federal presidential elections in February.

Al Shabaab conducted complex attacks in the Lower Shabelle region’s Barire and Awdheegle towns in early April. The towns have bridges that provide access into Mogadishu and host Somali National Army (SNA) bases whose missions include preventing al Shabaab from crossing into Mogadishu with explosive-laden vehicles. Al Shabaab detonated suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs) at the SNA bases in Barire and Awdheegle on April 3. Militants then clashed with troops at Barire before the SNA regained control of the base. Al Shabaab prevented reinforcements from arriving at the bases by targeting soldiers with a SVBIED near Lafole, about 22 miles east of Barire, the day of the attack. Al Shabaab circulated photos of the damage and casualties it caused at Barire on April 5.[ii]

Al Shabaab previously controlled Barire and nearby villages. Militants damaged Barire’s bridge in September 2017. It remained unrepaired at least until June 2019. African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and SNA forces *recaptured Barire from al Shabaab in April 2019. Security forces have clashed with al Shabaab in the area since.

The controversial extension of the Somali president’s term is unlikely to end the country’s political crisis. The SFG failed to hold federal presidential elections in early February and has been *unable to organize elections since. Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo” signed a law on April 13 that extends his presidential mandate for two years. This comes after Somalia’s Lower House of Parliament voted on April 12 to hold direct federal presidential elections in 2023. Somalia’s Upper House of Parliament deemed the vote unconstitutional. The vote has already caused tension among security personnel. Mogadishu’s police chief attempted to unilaterally suspend Parliament to prevent the vote but the country’s police commissioner relieved him of duty.

Ethiopia

Fighting in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region is concentrated north of the regional capital Mekelle. Ethiopian federal forces claimed victory over the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in November 2020 when they seized Mekelle. Fighting has continued since, however. Eritrean forces have continued deploying to Tigray to support fighting the TPLF. Eritrea’s continued involvement in Tigray contradicts Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s promise in late March that Eritrean forces would withdraw from the region. Limited reporting indicates that Eritrean forces most recently deployed to Tigray through Rama, an Ethiopian town along the Eritrean-Ethiopian border, around April 12. This latest deployment of Eritrean forces moved northward from Rama toward Axum and Adwa towns, northwest of Mekelle.

Ethiopia simultaneously faces ongoing tensions with Sudan. Sudan and Ethiopia’s border tensions have continued since December 2020, when Sudanese forces took advantage of Ethiopia’s distraction with the Tigray conflict to seize disputed land. The tensions most recently *caused Sudan to request that the UN replace Ethiopian soldiers with soldiers from another nation to the peacekeeping mission in Sudan’s disputed Abyei territory on April 6. This occurred on the same day that Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt failed to reach an agreement on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) during talks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sudan and Egypt rejected Ethiopia’s *request to share data on GERD operations on April 10 as Ethiopia unilaterally plans a second filling of the GERD this July. A possible military conflict between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan over natural resources would further threaten Ethiopia’s and eastern Africa’s stability.

North Africa

Libya

Libyan National Army (LNA) commander Khalifa Haftar and his external backers launched an effort to gain popular support before Libyan elections in December 2021. Haftar may be planning to run as a presidential candidate in the UN-facilitated elections, which aim to create a unified Libyan government. Haftar *announced that the LNA’s Military Investment Authority will construct three new cities in the Benghazi area that will include roughly 20,000 housing units designated for families of “martyrs” who died fighting for the LNA. This announcement comes as Benghazi, the largest city in LNA-controlled eastern Libya, is experiencing an uptick in violence. Signs of fragmentation in the LNA, including within its leadership, indicate that Haftar’s position has become more vulnerable since the end of his attempted takeover of Tripoli in June 2020 and the formation of the new transitional government in February 2021. Haftar hosted a meeting with new armed forces officers, including heads of the LNA land, sea, and air forces, on April 5, signaling an effort to solidify his position.

Haftar is leveraging his external ties to maintain influence and gain popular support in eastern Libya. The ambitious city-building plan likely reflects support from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a longtime LNA backer, though the LNA has also amassed significant resources by embedding itself into the eastern Libyan economy. Haftar also leveraged his ties with Russia and the UAE to facilitate the delivery of thousands of Russian Sputnik COVID-19 vaccines into Libya in an effort to gain popular support. Libya’s interim Government of National Unity (GNU) also announced that it *coordinated with Turkey on April 12 to bring thousands of Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines into Libya. Haftar may also be trying to strengthen relations with Egypt, which has historically supported the LNA but has signaled willingness to work with the transitional government. Haftar announced publicly that he wants to give Libyan citizenship to 10 million Egyptians. Egypt will benefit from resettling millions in Libya as the country is dealing with a rapidly growing population and limited resources. Several Benghazi municipal leaders *met with an Egyptian delegation to discuss reopening a consulate in Benghazi on April 8.

West Africa

Sahel

French-backed UN forces thwarted a large-scale Salafi-jihadi attack on a UN base. Chadian peacekeepers in the UN’s Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) killed at least 40 Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) members on April 2. JNIM militants attacked a MINUSMA base in Aguelhoc in northern Mali, and MINUSMA forces repelled the attack with assistance from the French Operation Barkhane. MINUSMA Chief Mahamat Saleh Annadif claimed that the soldiers killed a JNIM lieutenant Abdullah ag Albaka in the attack, however, photos indicate that the body in question is JNIM militant Abu Khaled al Tunisi, who is much younger than Albaka. JNIM militants *wore Chadian army uniforms in an attempt to obscure their identities during the attack. Aguelhoc residents *called on MINUSMA to relocate the base, fearing that it will attract another JNIM attack.

A peace agreement between JNIM and ethnic militias may be breaking down. The pastoralist Fulani and the agriculturalist Dogon ethnic groups compete for access to land and water in central Mali. Violence between the Fulani and Dogon has escalated since 2015, when Salafi-jihadi groups, most notably JNIM, began attacking the Dogon and fueling a cycle of retaliatory attacks. Salafi-jihadi militants have stoked the Fulani-Dogon clashes while presenting themselves as a potential security guarantor. JNIM has exploited local violence to gain access to local communities by promising protection and allying with vulnerable Fulani populations.

JNIM has recently intensified its efforts to cement its position in central Mali through a combination of military pressure and negotiations. A majority-Fulani JNIM subgroup, the Macina Liberation Front (MLF), besieged the village of Farabougou in central Mali’s Niono region in October 2020, and the Malian Army has since *claimed to have liberated the town. Members of Mali’s High Islamic Council (HIC), an independent religious body, facilitated an oral *cease-fire agreement between Dogon militias and MLF militants on March 14. The agreement states that residents of Niono will be allowed to move freely for one month and that the MLF will release a dozen prisoners. Dogon militias will in exchange allow Salafi-jihadi militants to enter and preach in Niono villages.

The leader of the powerful Dogon militia group Dan Na Ambassagou, Youssof Toloba, claimed on April 5 that he and his men will not abide by the peace agreement and vowed to continue the fight against JNIM militants. The Dan Na Ambassagou is active throughout central Mali and may encourage Dogon militias within Niono to reject the cease-fire agreement. Toloba’s statement builds on early signs of cracks in the cease-fire. MLF militants clashed with Dogon militias in Niono’s Dogofry village on March 15, one day after the cease-fire announcement.

Lake Chad

The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) is attacking aid workers to seize resources. ISWA militants *loaded their vehicles with supplies after attacking several aid warehouses carrying relief supplies in Damasak town in Borno state on April 10. ISWA has conducted several attacks against aid workers in Borno since December 2020. The April 10 raids were part of a larger attack against a Nigerian military camp, indicating that ISWA entered the town with plans to target both Nigerian security forces and aid workers.

ISWA is sustaining its operations on multiple fronts. ISWA conducted attacks in Cameroon, *Niger, and Chad throughout April while continuing its primary campaign in Borno.

[i] This insurgent group goes by many names, and the group itself has not declared one. CTP refers to the group as the Islamic State in Mozambique (IS-M). This choice should not be taken as an overstatement of the group’s relationship to Islamic State leadership nor as a dismissal of the complications inherent in assessing a group’s ideology, composition, or affiliations. For more on naming, see page 5 in Emily Estelle and Jessica Trisko Darden, Combating the Islamic State’s Spread in Africa: Assessment and Recommendations for Mozambique, Critical

Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, February 24, 2021, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/combating-the-islamic-states-spread-in-africa-assessment-and-recommendations-for-mozambique.

[ii] SITE Intelligence Group, “Shabaab Provides Photo Report Documenting Suicide Raid on Somali Base in Barire, Incites Fighters to ‘Redouble Jihad’,” April 5, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.