Africa File: Political crises rock Chad and Somalia; Islamic State insurgency robs Mozambique of billions

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Political crises in Chad and Somalia risk expanding into larger conflicts while lifting pressure from Salafi-jihadi groups in several African regions. Longtime Chadian President Idris Deby was killed amid fighting with rebel groups. The Chadian military has moved to take control of the country, including cracking down on protests against military rule. Chad is a base for Western counterterrorism forces and a regional troop contributor whose domestic instability will disrupt operations against Salafi-jihad groups in Mali and the Lake Chad Basin.

Unrest has also seized Somalia’s capital following the president’s attempt to extend his term by two years. The country’s security forces are fragmenting, and rival factions have staked out positions in the capital. Former allies pressured the president to abandon the term extension on April 27, possibly averting an immediate conflict, but Somalia’s political crisis will not be easily resolved. Meanwhile, al Shabaab—al Qaeda’s East Africa affiliate—has already exploited the crisis to bolster its positions in the Somali countryside.

Salafi-jihadi insurgencies are already exacting a steep cost in Africa in both lives and dollars. The French company Total suspended a multibillion-dollar investment in Mozambique this week due to an Islamic State–linked insurgency in the country’s north. The loss of the project—the largest source of private investment in Africa—is a devastating blow to Mozambique’s pursuit of economic growth. As CTP Research Manager Emily Estelle recently argued in Foreign Policy, “Africa’s rise to prosperity could be the defining story of the coming decades. But that won’t happen if hundreds of thousands lives under Salafi-jihadi dominance, with huge swathes of terrain becoming permanent terrorist havens, and millions displaced by violence.”

In this Africa File:

- Lake Chad. Domestic instability is disrupting Chadian involvement in regional counterterrorism efforts. The Islamic State’s West Africa Province is escalating sophisticated attacks on security forces in Nigeria.

- Sahel. An Al Qaeda–linked group is intensifying its efforts to control populations in central Mali by clashing with rival armed groups.

- Somalia. Somalia’s president backed away from an attempted power grab as rival factions grapple for control of Mogadishu, leaving al Shabaab to fill security vacuums outside the capital.

- Mozambique. A multibillion-dollar natural gas project was suspended in northern Mozambique following escalating attacks by an Islamic State–linked group.

- Ethiopia. Ethiopia’s June elections are a flashpoint for insecurity that threatens the country’s cohesion.

- Tunisia. The murderer of a French policewoman may have been in contact with a Tunisia-based Salafi-jihadi group.

Latest publications:

- Africa. Emily Estelle writes in Foreign Policy that Salafi-jihadi insurgencies in African countries get short shrift in Western policy circles. She argues that, as Salafi-jihadi groups notch success after success in Africa, political and policy challenges are preventing policymakers from seeing the threat clearly. But the spread of Salafi-jihadi insurgencies undercuts other US policy goals in Africa and, most importantly, robs millions of Africans of future prosperity and peace. Read the piece here.

- Chad. Rahma Bayrakdar assessed the implications of Chad’s domestic instability for the Salafi-jihadi movement in West Africa. Read the warning update here.

Read Further On:

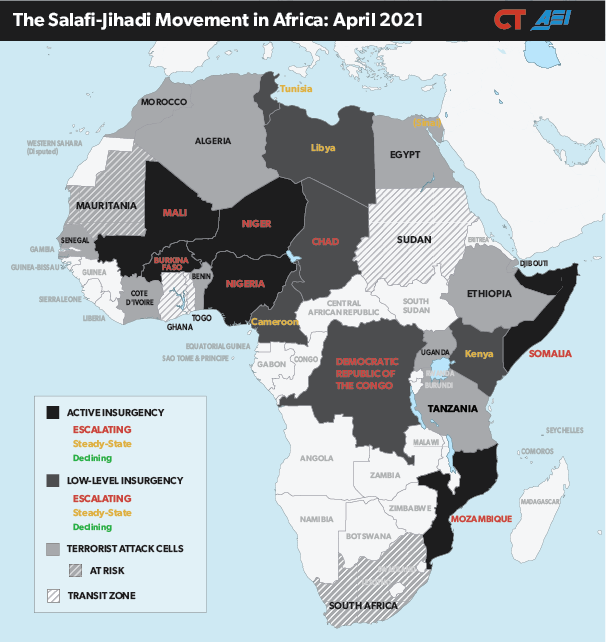

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: April 2021

View full image.

Source: Emily Estelle.

Overview: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated April 27, 2021

The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is active across northern, eastern, and western Africa and is expanding and deepening its presence on the continent. This movement, like any insurgency, draws strength from access to vulnerable and aggrieved populations. Converging trends, including failing states and regional instability, are creating favorable conditions for the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion. Meanwhile, counterterrorism efforts rely on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding, and on states and local authorities that have demonstrated an inability to govern effectively.

West Africa. The Salafi-jihadi movement has spread rapidly in West Africa by exploiting ethnic grievances and state weaknesses that include human rights abuses, corruption, and ineffectiveness. An al Qaeda affiliate co-opted the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and has continued to expand southward through the Sahel region into central Mali and the peripheries of Burkina Faso. An Islamic State–linked group is active in the same area, particularly western Niger. Sahel groups have not yet plotted attacks outside West Africa but have sought to drive Western security and economic presence out of the region while building lucrative smuggling and kidnapping-for-ransom enterprises. An al Qaeda–linked group in Mali is infiltrating governance structures, advancing an overarching Salafi-jihadi objective, and expanding into Gulf of Guinea countries. West Africa has become an area of focus for transnational Salafi-jihadi organizations, with rival jihadists now fighting for dominance in the Sahel.

The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate is based in northwest Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—and conducts frequent attacks into neighboring Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Boko Haram and an al Qaeda–linked splinter group are also active in this region.

New instability in Chad, whose security forces are engaged in counterterrorism efforts in Mali and the Lake Chad basin, may lift pressure from Salafi-jihadi groups in both theaters.

East Africa. Al Shabaab, an al Qaeda affiliate and the dominant Salafi-jihadi group in East Africa, is vocal about its intent to attack US interests and has begun to plot international terror attacks. The group enjoys de facto control over broad swathes of southern Somalia and can project power in the Somali federal capital Mogadishu and regional capitals, where it regularly attacks senior officials. It seeks to delegitimize and replace the weak Somali Federal Government (SFG)—a task made easier by endemic political dysfunction, corruption, and now open conflict in Mogadishu. Al Shabaab’s governance ambitions extend to ethnic Somali populations in Kenya and Ethiopia, and the group conducts regular attacks in eastern Kenya.

Al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from eroding security conditions in East Africa. Ethiopia’s destabilization is already having regional effects, including weakening counter–al Shabaab efforts in Somalia. The drawing down of the US and African Union counterterrorism missions in Somalia will also reduce pressure on al Shabaab.

The Islamic State has also penetrated the region. Islamic State branches are now active in northern Somalia, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Mozambique, bordering Tanzania. The insurgency caused the French company Total to shutter a multibillion-dollar natural gas project in northern Mozambique that was the continent’s largest private investment. The Islamic State foothold in Mozambique also marks the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion into southern Africa.

North Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups in North Africa are at a low point, but the fragility and grievances that led to their rise remain. The Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent security vacuums allowed Salafi-jihadi groups to organize and forge ties with desperate and coerced populations. The Islamic State’s rise brought a peak in Salafi-jihadi activity in North Africa, particularly from its branches in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Counterterrorism pressure has weakened Salafi-jihadi groups across North Africa in the past five years.

The insurgencies in Libya and the Sinai are active but contained, and terrorist attacks across the region have decreased. Libya’s political and security crisis will continue to create opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups, and severe instability or collapse in any North African state would likely bring the Salafi-jihadi threat back to the surface.

West Africa

Lake Chad

Domestic instability is disrupting Chadian involvement in regional counterterrorism efforts, benefiting Salafi-jihadi groups that are already on the offensive in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin. Chad faces an unpredictable political and security crisis. The country’s longtime president, Idris Deby, died on April 20 from wounds sustained during clashes with rebel groups north of the Chadian capital, N’Djamena, on April 19. A council of military officers established a transitional government and named President Deby’s son, Mahamat Kaka, interim president on April 20 in violation of the country’s constitution. Chadian opposition parties *denounced the coup.

Chad’s military leaders named Albert Pahimi Padacke, a former prime minister and Deby ally, as prime minister of the transitional government on April 26 over the objections of opposition leaders. Chadian security forces have killed at least two civilians protesting against the military takeover as of April 27.

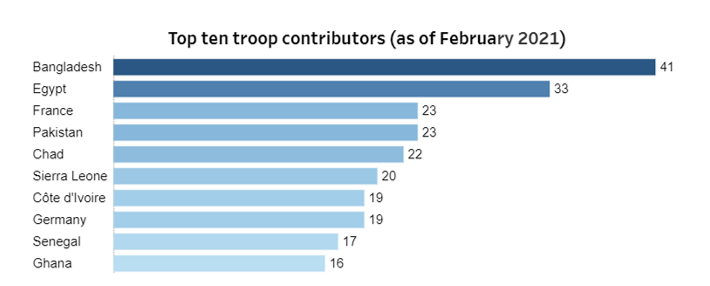

The withdrawal of Chadian forces, which are the most effective Sahelian force participating in regional counterterrorism efforts, will lift pressure from Salafi-jihadi groups in the Lake Chad and Sahel regions. Events in Chad may already be drawing Chadian forces away from the UN counterterrorism mission in Mali; 1,200 Chadian soldiers joined MINUSMA in March but are now *preparing to return home. Chad is one of the top troop contributors to MINUSMA with a contribution of nearly 1,500[1] soldiers before the March deployment. (See Figure 2.)

Internal unrest also threatens Chad’s border security and may benefit the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) and Boko Haram, both of which are active on the Chad-Nigeria border. The Chadian presence along its Lake Chad border since 2015 has prevented sustained incursions by ISWA or Boko Haram, but a domestic crisis that draws forces away from this region could allow Salafi-jihadi militants to secure a foothold on Chadian terrain. ISWA claimed an attack that killed 12 Chadian soldiers in western Chad’s Lac province near the Nigerian border on April 26, 60 miles north of Chad’s capital, N’Djamena. ISWA will likely conduct future attacks in this area given its ability to retreat to its base across the border in Nigeria. The Chadian army may not be able to repel future ISWA border attacks if soldiers are relocated to protect N’Djamena. Read more about how the crisis in Chad threatens West Africa counterterrorism efforts here.

Figure 2. Top 10 Troop Contributors to MINUSMA

Source: UN Nations Peacekeeping, “MINUSMA Fact Sheet,” February 2021, https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusma.

ISWA is expanding its area of operations in northeastern Nigeria. ISWA militants attacked a Nigerian military base and killed over 30 Nigerian soldiers in Mainok in northeastern Nigeria’s Borno state on April 25.[2] The militants entered Mainok in military camouflage and mine-resistant vehicles. The militants set fire to part of the town before retreating due to Nigerian airstrikes.

ISWA militants have been attacking regularly in the area between the Nigeria-Niger border and the Borno regional capital Maiduguri since December 2020. Targeting Mainok, which is located roughly 30 miles west of Maiduguri, may indicate the group’s plans to surround and isolate the city. ISWA’s use of military vehicles paired with its increasing use of explosive capabilities, such as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices, indicates that the group will continue to inflict high casualties on Nigerian security forces even at fortified bases.

Sahel

An al Qaeda–linked group is intensifying its efforts to control populations in central Mali by clashing with rival armed groups. Members of the pastoralist Fulani and the agriculturalist Dogon ethnic groups compete for access to land and water in central Mali. Violence between the Fulani and Dogon has escalated since 2015, when Salafi-jihadi groups, most notably al Qaeda–linked Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), began attacking the Dogon and fueling a cycle of retaliatory attacks. Salafi-jihadi militants have stoked the Fulani-Dogon clashes while presenting themselves as a potential security guarantor. JNIM has exploited local violence to gain access to communities by promising protection and allying with vulnerable Fulani populations.

JNIM has recently intensified its efforts to cement its position in central Mali through a combination of military pressure and negotiations. A majority-Fulani JNIM subgroup, the Macina Liberation Front (MLF), is attempting to impose its will on Djenne and the surrounding areas in Mopti region by force. MLF militants have been gathering rice from villagers in Djenne as part of the zakat (religious tax). Dozo hunters seized a portion of the rice in mid-February.

Dozo are traditional hunters in central and southern Mali and the surrounding regions whose ranks include Dogons and members of other ethnic groups. The MLF has since *clashed with Dozo hunters in Djenne. MLF militants killed seven Dozos in their most recent attack in Djenne and burned part of the town on April 21. The MLF has also targeted nearby villages after civilians *fled the fighting in Djenne. The MLF’s involvement in Djenne *disrupted an inter-community peace agreement from August 2019.

The MLF is also facing resistance in Niono, 128 miles west of Djenne in Segou Region. The leader of the powerful ethnic Dogon militia group Dan Na Ambassagou announced on April 5 that he and his men will not abide by a March 14 peace agreement between MLF and a Dogon militia in Niono and vowed to continue fighting JNIM. Da Na Ambassagou, which operates throughout central Mali, has been clashing with the MLF since. MLF militants attacked a Da Na Ambassagou position in Mopti Region’s Bandiagara on April 23–24. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. April 2021 MLF Activity in Central Mali: Key Locations

Source: Authors.

Salafi-jihadi militants kidnapped and killed foreign journalists and a wildlife expert in eastern Burkina Faso. Unidentified militants kidnapped at least two Spanish journalists and an Irish wildlife advocate who were filming a documentary in a national park bordering Benin on April 26. Burkinabe authorities found the journalists’ bodies the next day. JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) both operate in eastern Burkina Faso and have kidnapped foreigners in the Sahel region. The Associated Press reported on an alleged JNIM audio recording claiming the attack, but neither JNIM nor ISGS have released photos or videos of the incident at time of writing.

East Africa

Somalia

Political and security trends in Somalia are lifting pressure from al Qaeda’s East African affiliate al Shabaab. Al Shabaab has demonstrated an intent to conduct external attacks, including a 9/11-style attack on the US. Security trends in Somalia favor the group as the US troop withdrawal and drawdown of Ethiopian forces contributing to counterterrorism efforts in Somalia will reduce pressure on al Shabaab. A political and security crisis is now rocking Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, following the president’s attempt to extend his term until 2023.

Somalia’s president backed away from an attempted power grab as rival factions grapple for control of Mogadishu. SFG President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo” abandoned an attempt to extend his term by two years on April 27. The SFG had failed to hold elections amid political deadlock with the leaders of federal member states. President Farmajo’s term expired in February.

Farmajo’s support base deteriorated rapidly in the past week, with senior political and security leaders—including the prime minister and other former allies—turning against his attempt to hold onto power. Somalia’s armed forces have fragmented during the political crisis, with soldiers fighting for anti-Farmajo clan leaders taking control of strategic parts of the city. Rival forces clashed in Mogadishu on April 25. The hostilities included *clashes between Turkish-trained SFG units and hundreds of Somali National Army (SNA) soldiers that defected from their positions in Middle Shabelle region to oppose Farmajo in Mogadishu. Fear of a larger conflict has driven some civilians to flee the city.

Al Shabaab has sought to capitalize on the political turmoil by targeting police and government officials in Mogadishu. Somalia’s police commissioner fired Mogadishu’s police chief on April 11 for attempting to prevent the parliamentary vote to extend Farmajo’s term. Al Shabaab has been attempting to inflame existing security sector tensions by escalating attacks on strained police forces. Al Shabaab *claimed to attack at least two police stations in Mogadishu’s Mohamud Harbi and Bar Ubah neighborhoods on April 14. Suspected al Shabaab militants *killed a Wardhigley district official on April 16, the same day SNA troops clashed with security forces loyal to the fired police chief.

Al Shabaab seized a town after security forces left for Mogadishu. SNA forces withdrew from Ba’adweyne town in central Somalia’s Mudug region on April 14 to *focus on political tensions in the capital. Al Shabaab seized the town on April 15, filling the security vacuum, and may seek to *seize other towns in the area.

Mozambique

French company Total indefinitely suspended its operations in northern Mozambique due to the deteriorating security situation. Total declared force majeure and confirmed the withdrawal of all its personnel from the Afungi peninsula site on April 26. Islamic State–linked militants overran a coastal town near the Total site in northern Mozambique in late March. The Total project is the largest private investment in Africa and was meant to drive Mozambique’s economic growth in the coming decades. The International Monetary Fund had projected 38 percent economic growth for Mozambique in 2021 in a 2016 forecast but has now revised its forecast down to just 2.1 percent to account for the disruption of natural gas plans and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s June elections are a flashpoint for insecurity that threatens the country’s cohesion. The Ethiopian federal government delayed planned elections from August 2020 to June 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The election delay was a catalyst for the current conflict between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Ethiopian federal government in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region.

The elections are also raising political tensions between the federal government and other regional states. Political parties in Somali regional state suspended election activities in mid-April, joining Oromia regional state parties that had already announced boycotts. A failure to hold elections in Oromia would delegitimize Abiy’s administration and heighten existing tensions among Oromo groups, the federal government, and neighboring states. The elections are also a source of tension among regional states, as evidenced by a dispute between Somali and Afar regional state officials over *polling *station sites.

Eritrea admitted to its military presence in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region for the first time. Eritrea’s information minister acknowledged on April 16 that Eritrean forces are present in Ethiopia, saying that Eritrea and Ethiopia have agreed that Eritrean forces will withdraw. The minister’s statement is likely a reaction to an April 15 statement by a UN official noting that Eritrean troops, which have been accused of human rights abuses, have not yet left Tigray despite international pressure and a promise by the Ethiopian prime minister. Eritrean forces have been present in Tigray at least since November 2020 to support Ethiopian federal forces against the TPLF.

North Africa

Tunisia

The murderer of a French policewoman may have been in contact with a Tunisia-based Salafi-jihadi group. A Tunisian man living in France, Jamal Qarshan, stabbed and killed a French policewoman near Paris on April 23. A French officer shot and killed Qarshan at the scene. Qarshan *called a suspected Salafi-jihadi group member living in Sousse in northeastern Tunisia before the attack. Tunisian authorities arrested the contact and are investigating his relation to Qarshan.

French authorities are looking through Qarshan’s *phone and computer to determine whether he received outside help. French authorities claim that Qarshan likely self-radicalized and found Salafi-jihadi propaganda on his phone. Qarshan had watched Salafi-jihadi propaganda shortly before the attack. Qarshan’s relatives claimed he was depressed and seeing a psychiatrist in Paris.

Counterterrorism pressure in Tunisia and neighboring Libya has reduced Salafi-jihadi activity in Tunisia in recent years. Militants linked to al Qaeda and the Islamic State retain a haven in a mountainous region in western Tunisia bordering Algeria, where they conduct regular defensive attacks targeting security patrols. Covert Salafi-jihadi networks remain active in Tunisia’s more populated coastal regions. Three Islamic State militants killed a Tunisian National Guard officer and wounded another in Sousse on September 6, 2020.

[1] UN Nations Peacekeeping, “Troop and Police Contributors,” February 28, 2021, https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/troop-and-police-contributors.

[2] SITE Intelligence Group, “ISWAP Claims 14 Deaths in Attack on Nigerian Military Post in Mainok, Capturing Multiple Vehicles and Weapons,” April 27, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.