Africa File: Mali–Wagner Group deal threatens counterterrorism gains in the Sahel

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Key takeaway: The lifting of counterterrorism pressure in West Africa’s Sahel region will allow Salafi-jihadi groups to intensify their efforts to take control of civilian populations and establish enduring havens in northern and central Mali. Strained relations between the French government and Mali’s postcoup government are complicating France’s planned drawdown of its counterterrorism mission. The Malian government’s pursuit of a security deal with Russian private military company Wagner Group will further disrupt counterterrorism efforts. The Mali-Wagner deal would advance Russia’s objectives in Africa, which include undermining and replacing French influence.

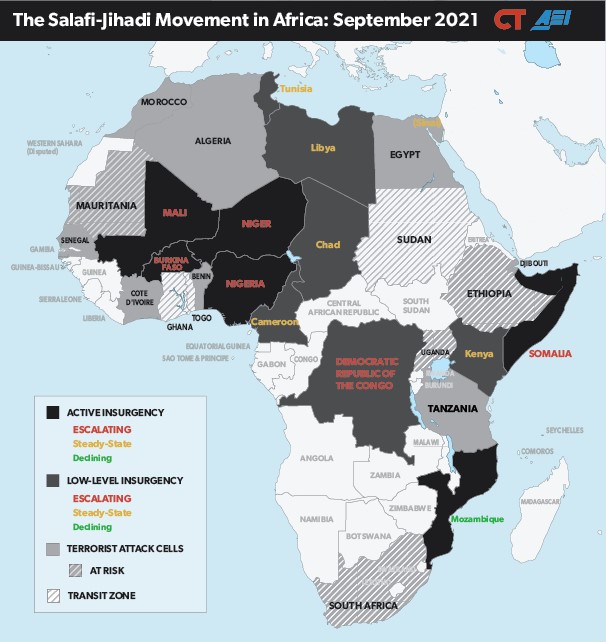

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: September 2021

View full map.

Source: Authors.

Read an overview of the Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa here.

French-Malian relations have become strained as Mali’s military junta consolidates power and France ends its counterterrorism mission in Mali. The junta ousted Mali’s civilian leaders in August 2020. The officers staged a second coup to solidify their power in May 2021, installing the coup’s leader as transitional president. French President Emmanuel Macron asserted that France will not work with Mali unless it transitions to democracy. France also suspended joint operations with the Malian military in June 2021. France resumed joint operations in July but has continued to pressure the junta to hold elections.

The planned French drawdown has also strained French-Malian relations. France plans to reduce Operation Barkhane, its counterterrorism mission in Mali, from 5,000 to 2,500 troops by early 2022. Barkhane will hand off some responsibilities to Task Force Takuba, a smaller European special operations mission. The remaining 2,500 French troops will support Task Force Takuba and Sahelian partners. France withdrew forces from several positions in northern Mali as part of the planned drawdown in early September 2021.

Malian officials have described this initial drawdown as “abandonment.” Malian officials are *skeptical about the French drawdown, suggesting France may “leave vast territories unprotected” and that Mali needs a “plan B,” a reference to the proposed deal with Russian private military company Wagner Group. French officials denied accusations of acting unilaterally, citing consultations between France, Mali, and other Sahelian countries. Mali’s transitional prime minister said Mali sought outside assistance to “to fill the gap” caused by the French drawdown in northern Mali. He also *accused France of “offering” Kidal in northeastern Mali to the Salafi-jihadi group Ansar al Din.

The Malian government will likely sign a security deal with Kremlin-backed private military contractor Wagner Group. Wagner Group will train the Malian military and protect senior Malian officials under the deal. Malian media *reported that Wagner Group will also protect two gold mines and one magnesium mine. Wagner may have deployed some personnel to Mali in August. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov confirmed that the Malian government reached out to “private Russian companies” in response to the planned reduction of French forces in Mali. Lavrov *discussed security cooperation with the Malian foreign minister at the UN General Assembly on September 24.

The Malian junta is pursuing the Wagner deal to retain power amid *international *pressure to hold elections, which it has sought to postpone. Mali’s Transitional Council, led by the 2020 coup leaders, has taken other steps to preserve its position, including passing two bills to protect coup participants from prosecution and imprisoning the former transitional president and prime minister in May 2021. The junta likely seeks to *use a deal with Wagner to resist French pressure and *solidify its hold on power by diversifying its ties to foreign militaries. Mali’s foreign minister signaled on October 12 that the junta may *delay elections, citing security concerns and foreign interference.

The reported Wagner Group deal does not include counterterrorism support. The Wagner Group will provide only 1,000 troops under the deal, and they will focus on training, personal protection, and infrastructure security. Even if Wagner offered a “plan B” to replace the French counterterrorism mission, it is unlikely to match the level of capability of French forces in Mali. The French mission will downsize to 2,500 troops by 2022 under the current drawdown plan, with an additional 600 European special operations forces under Task Force Takuba. The French presence brings additional capabilities, including US logistical and intelligence support.

France may accelerate its drawdown from Mali due to the Wagner Group’s presence. The French foreign minister said Wagner Group’s presence is “incompatible” with the French presence in Mali. The French defense minister *said that the international community will not support Mali in counterterrorism in the event of a Mali-Wagner deal. France may stop joint military operations with the Malian military or even accelerate its drawdown in response to the Wagner Group’s presence in Mali.

European resistance to a Mali-Wagner deal may also cause other European countries to contribute fewer forces to Task Force Takuba or the UN mission in Mali. Smaller troop contributions could render Task Force Takuba unable to backfill withdrawing French forces. Estonia *stated it would withdraw its 95 soldiers if the deal goes through. Germany *called the agreement between Wagner and Mali “contradictory” to international efforts, while the United Kingdom said it is closely reviewing the situation. The French defense minister also traveled to the Czech Republic to discuss cooperation in the Sahel, likely indicating an attempt to preserve the Czech commitment to Takuba in response to the Wagner deal.

The Mali-Wagner deal benefits Russia, which is taking advantage of strained French-Malian relations to advance its campaign of challenging French influence in Africa. Prior Kremlin-backed security and influence missions have targeted the Central African Republic, Guinea, and Madagascar, where Russia perceived France as unwilling or unable to contest growing Russian influence. Russia’s strategic objectives in Africa include countering Western influence and reestablishing Russia as a global power, including through expanding the Russian or Russian-backed military footprint through security assistance. Reports that Wagner—which functions as a Kremlin foreign policy tool—is recruiting Russians for the Mali mission indicate a high level of official Kremlin support for the Mali deal.

The Mali deal also advances Russian economic and resource-acquisition objectives in Africa. Russian objectives in Africa include *creating new revenue for Kremlin associates through the exploitation of natural resources. Mali has gold deposits in the west and south and unexploited *manganese and uranium deposits in the north. Russia has a shortage of manganese, an important industrial mineral. Russia may also seek to increase its influence in the Sahel because of the uranium mines in Mali’s neighbor Niger, though the Kremlin is unlikely to be able to challenge the strong French-Nigerien military and economic relationship under current conditions.

A diplomatic crisis between France and Algeria may also complicate the French mission in the Sahel and reflects a broader weakening of French influence in northwestern Africa. Algeria closed its airspace to French military air traffic after French President Emmanuel Macron questioned whether Algeria existed “before French colonization” on October 2. France also halved the number of visas granted to Algerians in 2021. The airspace closure has required military aircraft to take a more circuitous route to French positions in the Sahel. This wrinkle alone does not derail Operation Barkhane but signals the fragility of French positions, including its primary base in Niger, should the France-Algeria and France-Mali relationships continue to deteriorate.

Russia is positioned to capitalize on strained Algerian-French relations. Russia is expanding military relations with Algeria by selling weapons and equipment. Russia and Algeria held their first-ever joint exercise in the Russian Caucasus on October 3.

Forecast

Salafi-jihadi groups will exploit decreased counterterrorism pressure to expand and deepen their control of populations in northern and central Mali. Al Qaeda’s Sahel affiliate Jama’a Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) seek to impose their harsh version of governance and have expanded into central Mali and northern Burkina Faso in recent years. Counterterrorism pressure has inhibited these groups’ more ambitious plans but has not addressed the conditions that allow them to gain traction—leaving both JNIM and ISGS well prepared to expand should this pressure lift.

In the most likely case, French forces will accelerate their drawdown and European partners will reduce their deployments to Mali, complicating the transition and creating gaps among counterterrorism forces in the Sahel. An accelerated drawdown would create vacuums as France repositions assets. France closed three bases in northern Mali in early September as part of its planned drawdown. (See Figure 2.) European and Malian forces are currently *slated to *replace the French forces at the three northern bases. European concern over a Wagner-Mali deal may jeopardize this effort.

Figure 2: French Operation Barkhane Troops Withdraw from Mali Bases

View full map.

Source: AEI’s Critical Threats Project and Andrew Lebovich, “Mapping Armed Groups in Mali and the Sahel: Operation Barkhane,” European Council on Foreign Relations, May 2019, https://ecfr.eu/special/sahel_mapping/.

Salafi-jihadi groups would capitalize on this reduced pressure to consolidate their positions and possibly surge attacks during the transition period. One potential outcome is a surge in attacks along the Malian-Nigerien border, where ISGS is active and has been targeting civilians and security forces.

In a more dangerous case, French forces will withdraw entirely without sufficient backfill from Task Force Takuba. The Malian junta could cut ties with France to capitalize on increased domestic animosity toward the presence of French forces. Seventy percent of Bamako’s population approves of the Wagner deal and 8 percent of the population favors French forces, according to a recent survey. Likewise, French domestic pressure could push the French government to withdraw more rapidly, particularly if French forces suffer further casualties in Mali and the Malian government continues to issue anti-France statements.

Salafi-jihadi groups would gain significant freedom of movement in the Malian countryside in this scenario. JNIM would likely prioritize entrenching itself in local societies and establishing governance, including a shari’a court system. It may also feel emboldened to increase pressure on the Malian government and regional forces to withdraw from northern and central Mali by conducting terror attacks in Bamako and other Sahelian capitals. Both JNIM and ISGS would also intensify ongoing efforts to expand their networks into neighboring coastal states.