Africa File: Burkina Faso Coup Signals Deepening Governance and Security Crisis in the Sahel

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Key Takeaway: Burkina Faso’s latest coup on September 30 indicates that the governance and security crisis in West Africa’s Sahel region continues to deepen. Salafi-jihadi groups linked to al Qaeda and the Islamic State have exploited cyclical violence and anti-government grievances to root themselves in local communities and steadily expand in the Sahel over the past decade. The fallout from the Burkina Faso coup, like the 2020 and 2021 coups in Mali, will likely further reduce counterterrorism pressure and worsen the conditions that lead to Salafi-jihadi expansion.

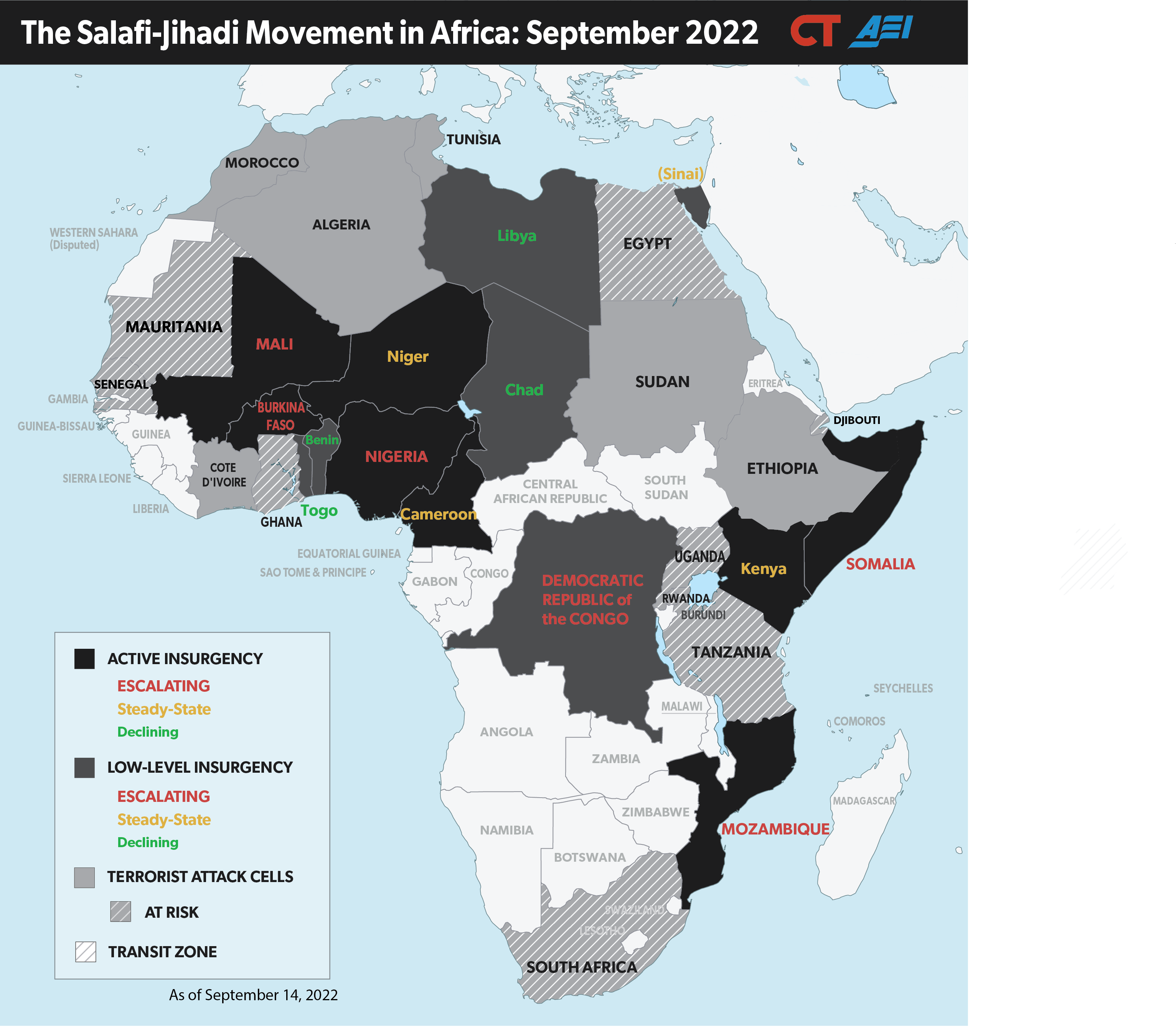

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: September 2022

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

Members of the Burkinabe military overthrew its government for the second time in 2022. Lt. Col. Paul-Henri Damiba took power on January 24 as part of a junta that suspended Burkina Faso’s constitution, dissolved the government, and arrested President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré. Capt. Ibrahim Traore overthrew Damiba’s government in a similar fashion nine months later on September 30. Damiba resigned on October 2, after several days of isolated skirmishes between pro- and anti-coup forces in the capital.

Salafi-jihadi activity in Burkina Faso helped create conditions for the coups, and major attacks preceded both military takeovers. Salafi-jihadi groups have rapidly expanded across Burkina Faso since 2016, causing massive internal displacement. The insurgency, which began in part as a reaction to security force abuses, has also led security forces and local ethnically based militias to increase violence against civilians—a dynamic that allows Salafi-jihadi groups to appeal to and impose themselves on vulnerable populations.

Two major militant attacks in northern Burkina Faso that altogether killed over 200 people in June and November 2021 sparked the protests that set conditions for the coup. Lt. Col. Damiba’s junta subsequently failed to prevent large-scale massacres on Burkina Faso’s periphery, where militants now hold more territory than they did when Damiba took power. This lack of progress,* alongside inter-military power struggles, led to the September coup. The coup occurred less than a week after militants attacked a supply convoy in northern Burkina Faso, killing at least 37 Burkinabe soldiers and civilians and wounding dozens more.

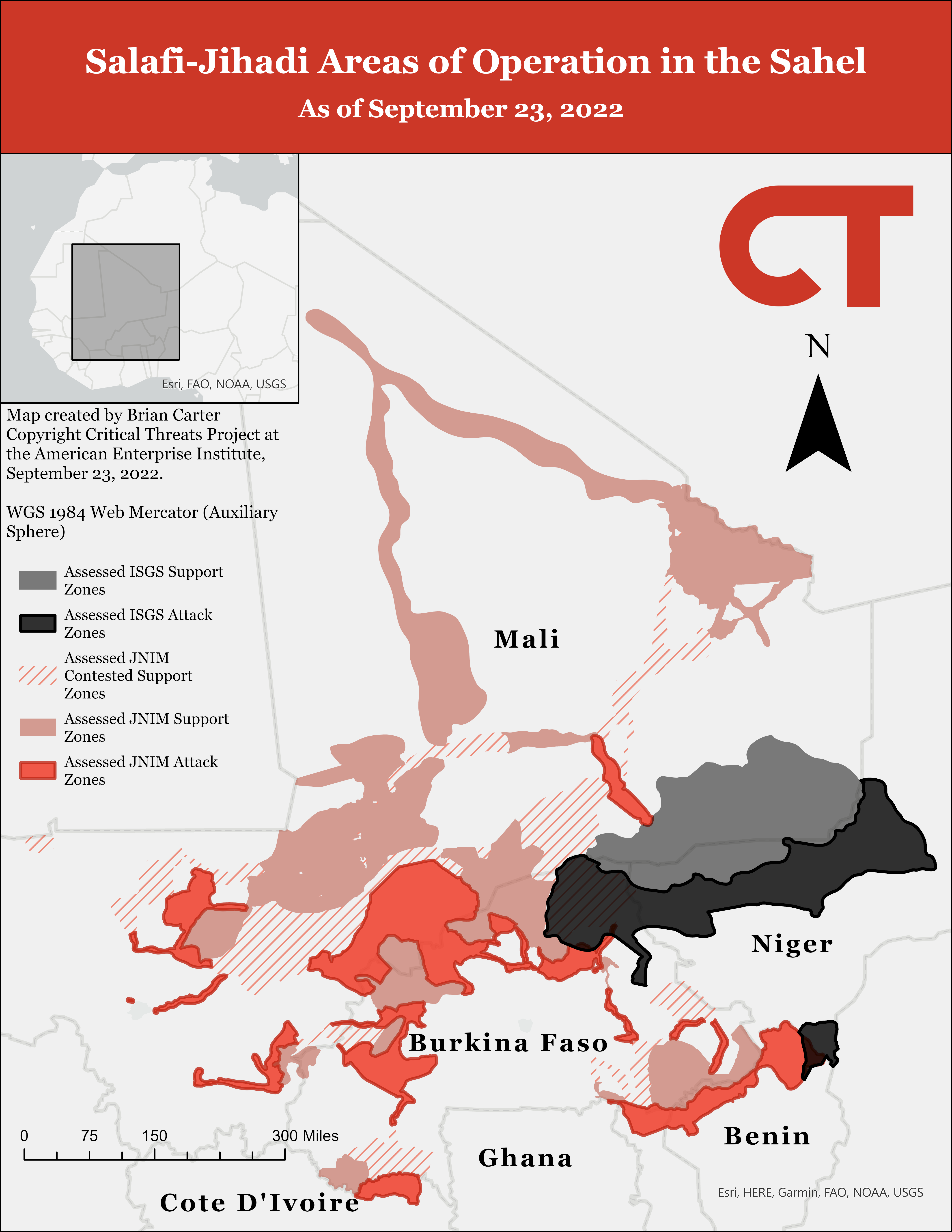

Burkina Faso’s latest coup comes as Salafi-jihadi militants consolidate control in their core terrain and spread to new areas. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) is active across Mali and Burkina Faso. JNIM is currently engaged in campaigns to isolate* population centers and implement its version of shari’a through shadow governance in rural areas. The Islamic State Sahel Province, more commonly known as Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS), operates primarily in the tri-border region of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. ISGS aims to consolidate control of population centers it has besieged* to carve out a territorial holding. Both groups are also taking advantage of growing local grievances and security vacuums, especially along Burkina Faso’s borders, to expand into the littoral Gulf of Guinea states.

Figure 2. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

Note: JNIM is Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen. ISGS is Islamic State Greater Sahara. For an interactive map of JNIM and ISGS’s area of operations, click here.

Source: Brian Carter.

Neighboring Mali has also faced increased instability following successive coups that have significantly weakened regional counterterrorism efforts. Members of the military overthrew the civilian government in August 2020. The coup followed months of nonviolent protests demanding the resignation of the Malian president due to corruption and instability stemming from the jihadist insurgency. A group of officers then overthrew the transitional government in May 2021 to consolidate its power.

The junta has taken an aggressive approach to affirming its sovereignty, leading to splits from its regional partners. Mali withdrew from the G5 Sahel joint counterterrorism force in May 2022, formalizing an ongoing lack of cross-border coordination. The junta recently angered its Ivorian neighbors and other regional partners by imprisoning 49 Ivorian peacekeepers it accused of being “mercenaries” in July 2022. Poor regional counterterrorism cooperation allows militants to maintain support zones in border areas, enabling cross-border operations and recruitment.

The junta’s takeover and decision to hire Russian Wagner* Group mercenaries in 2021 quickly soured relations with France and other European countries. The deteriorating partnership accelerated and expanded the planned withdrawal of French forces and some European special operations troops from Mali in August 2022. The Malian junta also imposed airspace restrictions on the remaining European forces in the United Nations peacekeeping mission, which has caused these forces to suspend operations and could trigger their withdrawal. Departing European partners are taking critical intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and medevac services with them. The loss of these capabilities gives militants increased freedom of movement and likely increases Malian army casualties.

The arrival of Wagner mercenaries also increased violence against civilians in conflict-affected areas of Mali. The junta reportedly pays Wagner Group $10 million per month to provide military training and protection for senior Malian officials. Wagner’s presence has increased the number and severity of violent incidents against civilians in its area of operations, which is spreading across Mali.

The new Burkinabe junta will likely seek different security partners, which could have similar effects on counterterrorism efforts as did the Malian coups. Russian information operations in the Sahel have exacerbated long-standing anti-colonial grievances against France and boosted pro-Russian sentiment. These trends were evident among coup supporters in Burkina Faso. The new junta leaders and influential Burkinabe politicians say they will diversify Burkina Faso’s security partners, including seeking a closer relationship with Russia. Wagner Group founder Yevgeny Prigozhin has also openly supported Traore, the September coup’s leader.

One of the junta’s first major actions was anti-French. It falsely accused* France of sheltering ousted President Damiba, sparking protestors to attack the French embassy and a French government-run cultural center in Ouagadougou. Protestors also attacked a French cultural center in Burkina Faso’s second largest city, Bobo Dioulasso. The new junta will likely continue to distance itself from France. This policy could restrict French support* and special forces based near Burkina Faso’s capital—and joint operations with Burkinabe forces.

Increased Russian involvement—especially the deployment of Wagner Group mercenaries—would likely challenge international counterterrorism support as it did in Mali. US intelligence assessed in July 2022 that the Wagner Group was mostly likely to expand into Burkina Faso as its next country. The US State Department spokesperson said the US had not seen any evidence of Burkinabe negotiations with Wagner but warned the new junta against seeking support from the group on October 4. Russia’s faltering invasion of Ukraine makes greater Wagner Group activity in West Africa unlikely, however. Wagner Group may already be encountering problems paying its forces in Mali and said on October 5 that all new recruits will be sent to Ukraine. The Burkinabe junta has also caveated its position on Russia to maintain good relations with other states by saying it wants to increase cooperation with all other partners, such as the US, and “not necessarily [just] Russia.”

The Burkinabe coup also threatens counterterrorism* coordination* between Niger and Burkina Faso, which has increased throughout 2022. Niger and other regional partners sanctioned Mali and Guinea following their coups to help expedite a return to civilian rule. A stronger Burkinabe-Russian relationship could also complicate relations with Niger, which hosts American and French troops. However, the Burkinabe junta has so far tried to maintain regional ties by agreeing to uphold a commitment to return to constitutional order by July 2024 and meeting a delegation of regional partners led by a former Nigerien president.

Weak and militarized governance will worsen relations between civilians and the military and help the Salafi-jihadi movement expand in the Sahel. The Malian junta has taken an overly forceful approach to counter militants and has permitted military abuses against civilians. Wagner Group’s presence has exacerbated this trend. Burkinabe coordination with Russian mercenaries would almost certainly increase violence against civilians if it occurred.

Militarized responses to JNIM and ISGS will increase jihadist recruitment and penetration of communities in the Sahel. Both groups have used previous cycles of retribution throughout the Sahel to impose their governance and present themselves as defenders of local communities. These communities have increasingly turned to JNIM and ISGS as they have lost confidence in local or national-level authorities and their allies to provide security. JNIM* and ISGS have already publicly responded to Wagner atrocities to gain legitimacy and brand themselves as local protectors.[1]

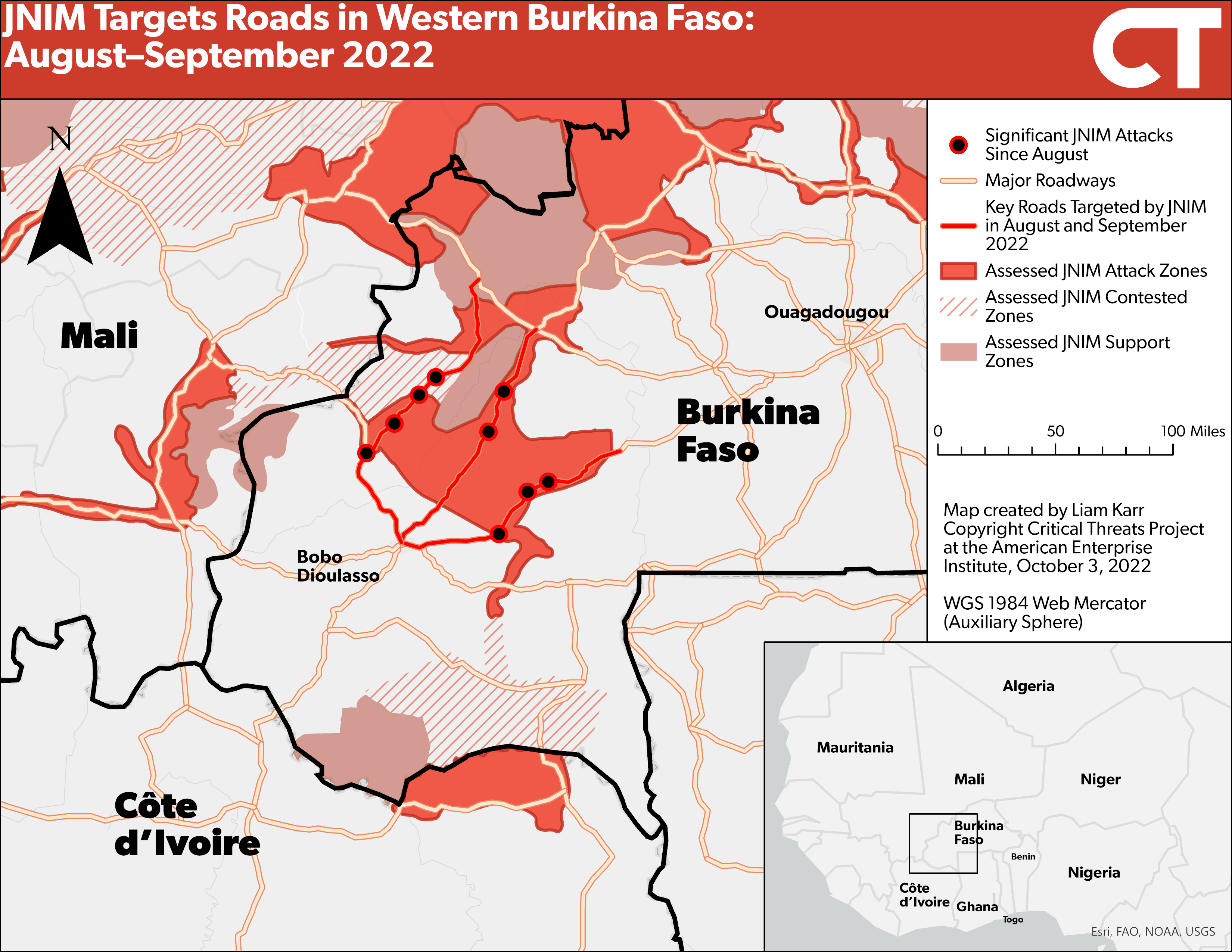

Instability in Burkina Faso may aid ongoing JNIM campaigns to consolidate its control of peripheral areas in Burkina Faso. JNIM has been using its havens along the Malian border and in rural Burkina Faso to target key ground lines of communication in western Burkina Faso, which connect the country’s northwest to its second largest city and economic capital, Bobo Dioulasso. The group escalated this campaign in early August, when it attacked* the Tuy provincial capital in Hauts-Bassins region for the first time. JNIM also rapidly* collapsed* the Banwa provincial government* in Boucle du Mouhoun in early September.

Figure 3. JNIM Targets Roads in Western Burkina Faso: August–September 2022

Note: JNIM is Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen.

Source: Liam Karr.

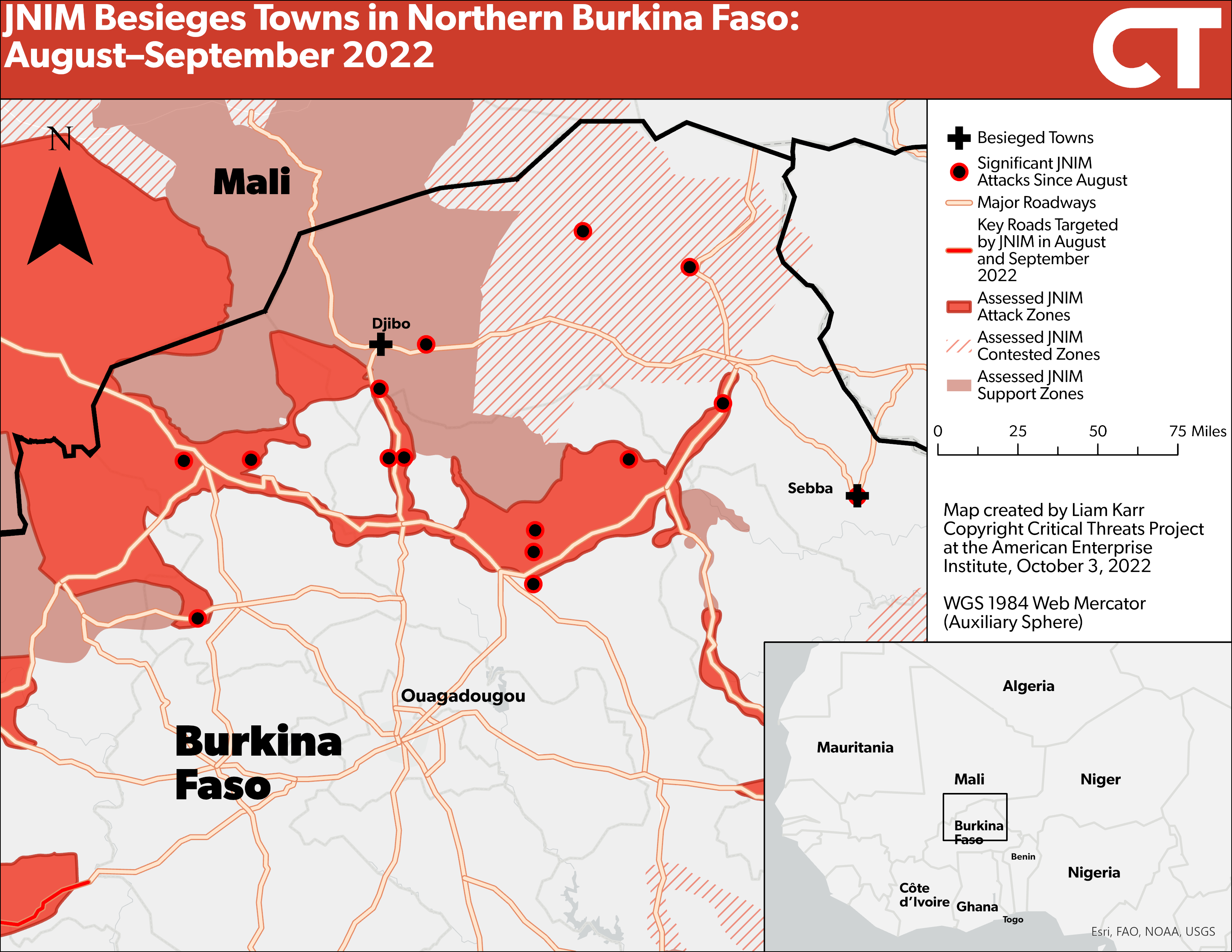

JNIM is also waging a campaign targeting ground lines of communication in northern Burkina Faso that is in a more advanced stage. The group has cut or severely restricted major roadways, consolidated control over rural areas, and besieged major population centers in northern Burkina Faso’s Sahel region. The persistent siege has forced these towns to the verge of humanitarian disaster and fanned the discontent* among security forces that led to the September coup.

Figure 4. JNIM Besieges Towns in Northern Burkina Faso: August–September 2022

Note: JNIM is Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen.

Source: Liam Karr.

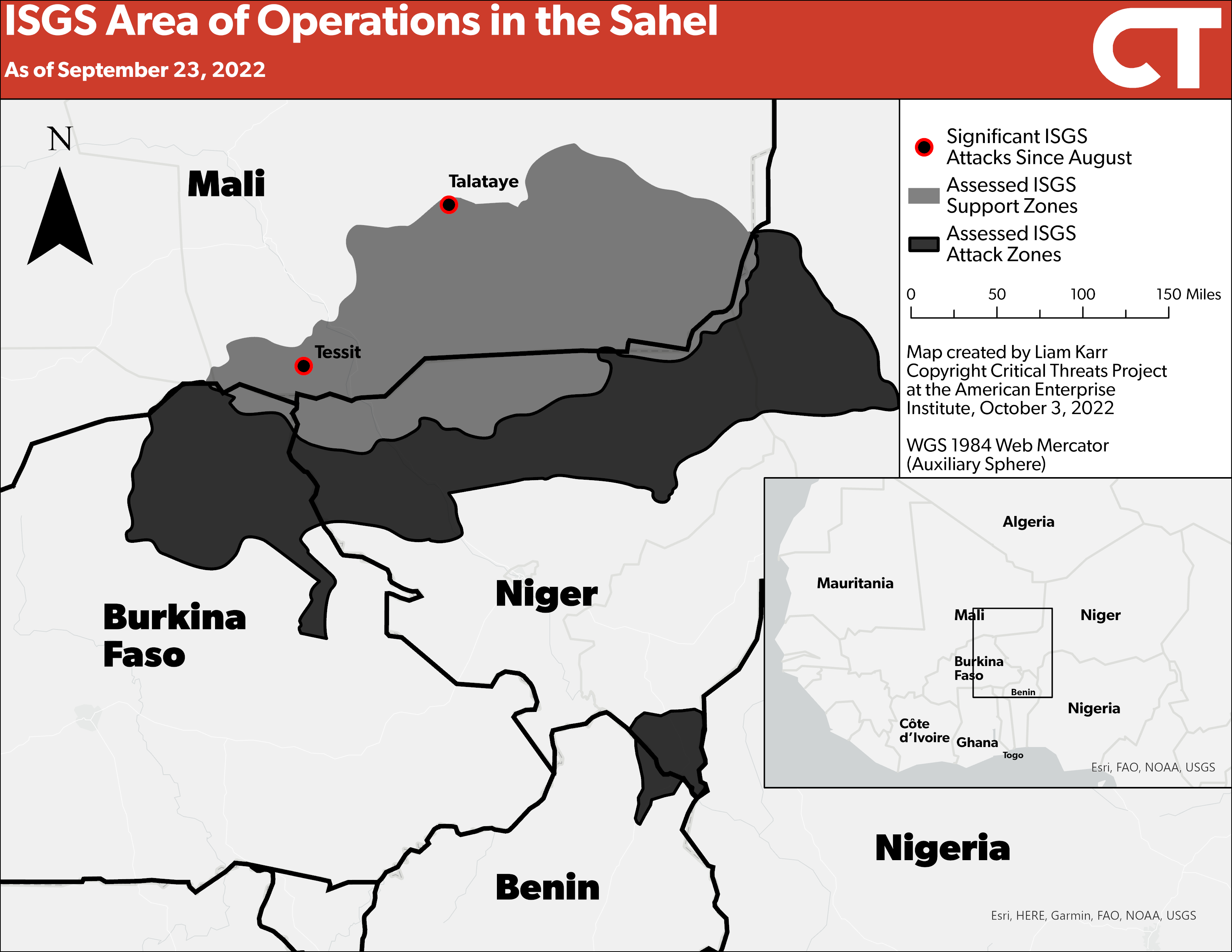

ISGS is strengthening and could benefit from instability that causes decreased counterterrorism coordination in the tri-border region. ISGS used surveillance drones to coordinate a complex attack in Tessit in northern Mali’s Gao region on August 10, overrunning* the town and killing at least 45 Malian soldiers and officials.[2] ISGS also killed at least 30 civilians and dozens of militants when it overran an anti-ISGS coalition of militia fighters aligned with the Malian government and JNIM fighters in the town of Talataye, nearly 150 miles northeast of Tessit, on September 6.[3] A Malian commander urged* citizens in the surrounding areas to flee on September 15, because militants were going to overtake the areas as there was “no security is there to stop them.” The Malian junta will likely continue to avoid joint operations, while the Burkina coup risks the remaining Nigerien-Burkinabe cooperation in the area.

Figure 5. ISGS Area of Operations in the Sahel as of September 23, 2022

Note: ISGS is Islamic State Greater Sahara.

Source: Liam Karr and Brian Carter.

Worsened security in Burkina Faso will likely enable Salafi-jihadi groups to intensify their expansion into Gulf of Guinea states. Salafi-jihadi groups have intensified attacks in littoral countries since the beginning of 2021. JNIM surged attacks in Côte d’Ivoire in early 2021, attacked* in Benin for the first time in 2021, and claimed first attacks in Togo amid a spike in likely JNIM violence in the country in July 2022. ISGS retroactively announced its presence in the littorals when it claimed two early July 2022 attacks in Benin in a September al Naba publication.[4] Salafi-jihadi groups use their havens in Burkina Faso as key transit points for their cross-border operations into littoral countries. Decreased counterterrorism cooperation and continued security vacuums along Mali and Burkina Faso’s peripheries will allow militants to conduct cross-border operations more easily in these countries.

The Gulf of Guinea states face some of the same internal challenges that Salafi-jihadi groups have capitalized on across the Sahel. The littoral states have been unable to quash incipient Salafi-jihadi insurgencies in their peripheries, although their governments have currently contained the violence on a much smaller scale than in Burkina Faso and Mali. The low-scale insurgencies persist in part due to farmer-herder conflict in the northern parts of the littoral states that create the intercommunal tensions that militants can manipulate. Ivorian security forces have also indiscriminately arrested ethnic Fulani civilians, creating security force abuses for jihadists to exploit. The littoral states have some advantages that may allow them to contain Salafi-jihadi activity. They are more politically stable than Burkina Faso and Mali, have demographic barriers to Salafi-jihadi expansion, and, in some cases, have more positive perceptions of security forces. Long-term militant havens in Burkina Faso will nonetheless challenge its littoral neighbors by facilitating simmering cross-border insurgencies in their sometimes-restive northern regions.

[1] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Reveals Responsibility for Attacks in Benin, Marking Expansion of ‘Sahel Province’ to Another Country,” September 15, 2022. Available by subscription at www.Siteintelgroup.com.

[2] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Reveals Responsibility for Attacks in Benin, Marking Expansion of ‘Sahel Province’ to Another Country.”

[3] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Reveals Responsibility for Attacks in Benin, Marking Expansion of ‘Sahel Province’ to Another Country.”

[4] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Reveals Responsibility for Attacks in Benin, Marking Expansion of ‘Sahel Province’ to Another Country.”