Islamic State Increases Attacks as Pakistani Taliban Negotiates

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

Key Takeaway: The Islamic State’s Pakistan Province (ISPP) is attempting to recruit from the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) as the TTP negotiates with the Pakistani government. ISPP has increased attacks since negotiations began in November 2021. The group also demonstrated renewed attack capabilities in October 2022, though its overall effectiveness remains limited. Government concessions to the TTP could also benefit ISPP and other Salafi-jihadi groups by increasing their access to safe havens in northwestern Pakistan.

The Islamic State’s Pakistan Province (ISPP) poses a latent threat in South Asia’s crowded militancy landscape but benefits from its integration with more-established groups. The Islamic State established ISPP in May 2019 by dividing the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) into separate branches for Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan. ISPP has since struggled to capitalize on local dynamics and establish footholds. It has likely survived due to its ongoing coordination and overlapping networks with ISKP. The UN reported in May 2022 that ISKP is co-located with the Islamic State’s al Siddiq administrative office, which oversees Islamic State affiliate activities throughout South and Southeast Asia. ISPP and ISKP are also allies with shared networks, and fighter loyalties to ISPP and ISKP are often blurred and fluid. Islamic State central directed ISKP in July 2021 to attack in northwestern Pakistan, where ISPP had previously operated, and ordered ISPP members in the northwest to begin following ISKP orders. ISPP and ISKP have largely maintained this division of operations.

ISPP and ISKP also have some overlying networks with the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an umbrella organization of anti-Pakistan militant groups affiliated with the Afghan Taliban and al Qaeda. ISPP’s current leader is a former TTP commander, and TTP defectors and other Pakistani militants formed ISKP in 2015. The UN reported in January 2020 that ISKP had established informal contacts with the TTP. ISPP, ISKP, and the TTP continue to claim some of the same attacks in Pakistan, which could point to a convergence in their operations and membership.

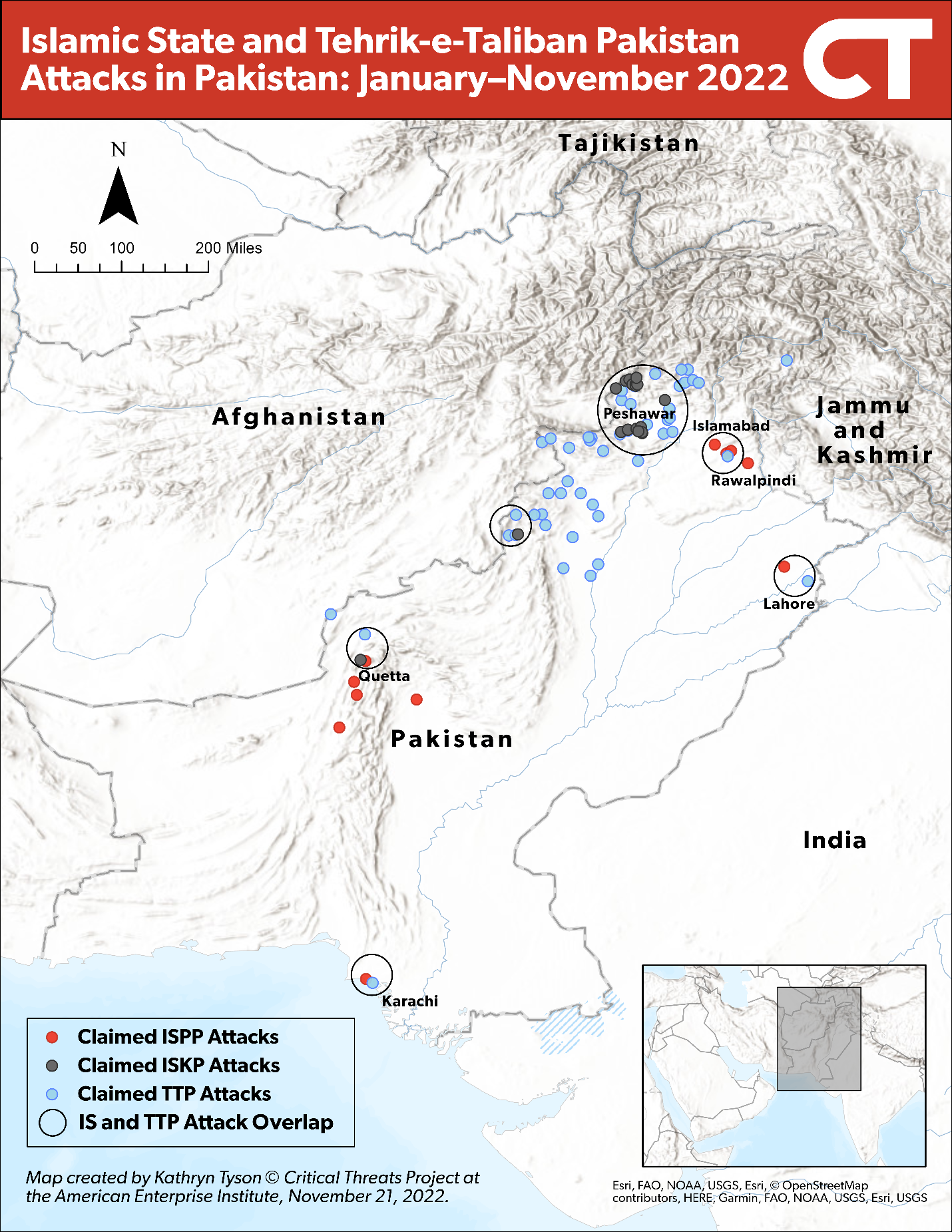

Figure 1. Islamic State and TTP Attacks in Pakistan: January–November 2022

Source: Author.

ISPP increased its rate of attacks in 2022 and has escalated attacks since September 2022. ISPP has claimed 15 attacks in 2022 so far, with eight of these attacks occurring in September and October. The group concentrated attacks in Balochistan province in southwestern Pakistan and Punjab province in eastern Pakistan. It has focused attacks in both provinces in previous years. This September–October surge is the largest number of ISPP attacks since 2019, when the group claimed 15 attacks. ISPP claimed approximately four attacks per year in 2020 and 2021. COVID-19 *lockdowns and a related increase in Pakistani military presence in these two provinces may have contributed to this lull.

ISPP returned to prior attack zones and renewed explosive attacks in October 2022. ISPP claimed to wound four security personnel during what was likely a raid on an ISKP hideout on October 1. This incident was ISPP’s first claimed attack in Karachi since May 2019. ISPP also used an improvised explosive device (IED) in an attack for the first time since May 2020. ISPP claimed it detonated two IEDs targeting alleged Pakistani intelligence agents in Mastung, southwestern Pakistan, on October 14. Most claimed ISPP attacks in 2022 have involved small-arms or grenade attacks. These attacks likely aim to degrade security forces’ abilities to disrupt ISPP or ISKP activities. ISPP also likely seeks to incite sectarian conflict by targeting religious minorities in attacks. The following is a list of ISPP attacks in 2022.

- January 30: An ISPP gunman assassinated a Pakistani policeman in Rawalpindi, Punjab.[i]

- March 8: ISPP detonated a suicide vest targeting Pakistani soldiers in Sibi, Balochistan, killing five soldiers and wounding 25 others.

- April 22: ISPP killed a “Christian” in Rawalpindi, Punjab.

- April 29: ISPP killed likely a Sufi in Mastung, Balochistan.

- April 30: ISPP killed likely a Sufi in Sheikhupura, Punjab.

- June 20: ISPP killed a “Shīʿah” in Islamabad.

- August 9: ISPP fired on a group of “Christians” in Mastung, Balochistan. The attack killed one person and wounded several more.

- September 19: ISPP fired on a Pakistani Counterterrorism Department (CTD) patrol and injured two CTD personnel in Quetta, Balochistan.

- September 30: ISPP killed likely a Sufi in Rawalpindi, Punjab.

- October 1: ISPP threw hand grenades and fired on CTD forces in Karachi, Sindh, and injured four CTD personnel.

- October 13: ISPP militants beheaded a Pakistani “informant” in Mastung, Balochistan.

- October 14: ISPP detonated two IEDs targeting Pakistani “spies” in Mastung, Balochistan. The attack killed three people and injured six others.

- October 21: ISPP killed a Pakistani “intelligence officer” in Rawalpindi, Punjab.

- October 25: ISPP killed a Pakistani police officer in Lahore, Punjab.

- November 12: An ISPP gunman killed a Pakistani “spy” in Qalat, Balochistan.

ISPP’s recent surge may aim to attract militants from other groups, particularly TTP members disillusioned with their group’s willingness to negotiate with the Pakistani government. The TTP and the Pakistani government *reached a temporary cease-fire in November 2021 and an indefinite cease-fire in June 2022. ISPP may be attempting to position itself as the main jihadist alternative to the TTP. ISPP condemned the TTP, al Qaeda, and the Afghan Taliban for abandoning jihad in December 2021 and again in August 2022. This criticism likely referred to the TTP’s negotiations with the Pakistani government, which the Afghan Taliban and members of the al Qaeda–linked Haqqani network have facilitated. ISPP also called on TTP members to disobey TTP leadership supporting negotiations with the Pakistani government, possibly encouraging defections. ISPP could recruit hard-line TTP members who oppose negotiations. ISKP similarly used the 2020 negotiations between the Afghan government and the Afghan Taliban to act as a spoiler and gain recruits. The TTP has reunited 10 splinter factions since 2020 after years of internal fighting, but the group remains decentralized and could split again.

ISKP’s comparative recruiting advantage may dampen ISPP’s ability to attract TTP fighters. ISKP and ISPP are linked groups that coordinate activities and share networks, but their overlap could have unintended trade-offs. ISKP, like ISPP, criticized the TTP over negotiations in July 2022 to attract TTP defectors. ISKP has also successfully recruited from the TTP in the past, and ISKP and the TTP currently operate in the same areas. ISPP and the TTP still likely have some overlapping networks in this region. Both groups claimed two of the same attacks in 2022 in Punjab province, eastern Pakistan. ISKP and the TTP may have more shared networks than ISPP, however. ISKP and the TTP have claimed at least six of the same attacks in 2022. ISKP also has a more active propaganda wing than ISPP and has adopted an aggressive propaganda strategy to attract militants from South and Central Asia.

ISPP has taken new steps to build its base in Pakistan and finance its operations. ISPP launched its first Urdu-language magazine called Yalghar (Invasion) in April 2021 to attract recruits, rally members, and discredit opponents, publishing three issues since 2021. The magazine targets a general Pakistani audience rather than a particular ethnic group or population from a specific region in Pakistan, likely to appeal to a larger pool of potential recruits. The magazine also courts Urdu-speaking fighters from India and Kashmir. ISPP’s use of emerging technologies to solicit donations could also help the group expand in Pakistan. The Yalghar issue in August 2022 included QR codes directing users to Telegram accounts, marking the first pro–Islamic State publication that has marketed QR codes to their audience. ISPP could collect cryptocurrency donations through this Telegram account. The US government has reported instances of other Islamic State branches soliciting cryptocurrency, enabling these groups to expand and disguising their funding efforts.

ISPP poses a lesser threat than other militant groups in Pakistan, but it could expand its footholds if domestic unrest worsens. Public confidence in Pakistani state institutions and the military is declining, and political unrest in Pakistan will likely increase in the coming months. The attempted assassination of former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan on November 3 ignited *protests across Pakistan, including in areas where ISPP has recently attacked. ISPP could capitalize on local distrust for propaganda value and recruitment. ISPP blamed the Pakistani government in August 2022 for record-breaking flooding in Pakistan and called for attacks. ISPP will likely continue to target Pakistani security forces and religious minorities in an effort to undermine Pakistani governance and security and spark sectarian violence.

Concessions to the TTP could present new options for ISPP and the wider Salafi-jihadi movement in Pakistan. Islamabad seeks to dissolve the TTP and transition it into mainstream politics. Pakistani negotiators indicate openness to some TTP demands, including a reduction of Pakistani military forces from northwestern Pakistan. Talks appear to be at a *stalemate and a force reduction is unlikely in the short term, but possible concessions to the TTP in the long term could benefit ISPP and other Salafi-jihadi groups. ISPP and ISKP could take advantage of a decrease in security forces in the northwest to develop stronger interlinkages and resource sharing. ISPP could then use the northwest as a support zone to launch more attacks further south and east. A troop reduction could also provide al Qaeda core and al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent—al Qaeda’s South Asia affiliate—with more options for safe havens. Islamic State and al Qaeda affiliates in other theaters have exploited force drawdowns and reduced counterterrorism pressure to secure havens and launch more cross-border attacks. ISPP and ISKP could attempt to do the same in Pakistan.

[i] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS and TTP Issue Competing Claims of Credit for Killing Policeman in Rawalpindi,” January 31, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.