Africa File: Al Qaeda–Linked Militants Take Control in Northern Mali

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Key Takeaway: Al Qaeda’s Sahel branch, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), is filling the security vacuum in northern Mali following the French withdrawal in 2022. JNIM is establishing itself as the primary partner and power broker for former rebel groups and communities in the north, an area where the Malian government has historically lacked presence. These communities face rising violence from both the Islamic State and the Russian Wagner Group, which partners with the Malian government. This trend will likely lead to JNIM establishing de facto control over northern Mali, a takeover that will feed long-term instability in Mali and its neighbors and increase the resources and opportunities available to al Qaeda in Africa.

The French withdrawal created a security vacuum in northern Mali. The end of France’s counterterrorism mission in November 2022 significantly reduced counterterrorism pressure that had disrupted the Salafi-jihadi militants’ freedom of movement. The Malian government has remained largely absent from northern Mali. The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is not designed to serve an active counterterrorism role.

The decrease in French counterterrorism pressure has allowed Salafi-jihadi militants greater freedom of movement. The French counterterrorism operation in Mali ultimately failed to end the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in the Sahel. This is largely because French and Western decision makers did not adequately address the sociopolitical and economic causes at the root of the conflict. Still, the French and European counterterrorism forces exerted enough military pressure to eliminate many terrorist leaders, help protect northern Malian cities, and contain the Islamic State affiliate in the area. The mission’s end has emboldened both JNIM and the Islamic State’s Sahel branch. Members of the Islamic State’s Sahel Province—also known as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS)—gathered in large numbers in northeastern Mali in a show of force when pledging to the new IS emir in December 2022. JNIM’s emir, Iyad ag Ghali, traveled throughout northern Mali in 2023 and made his first public appearance in two years in January.[1]

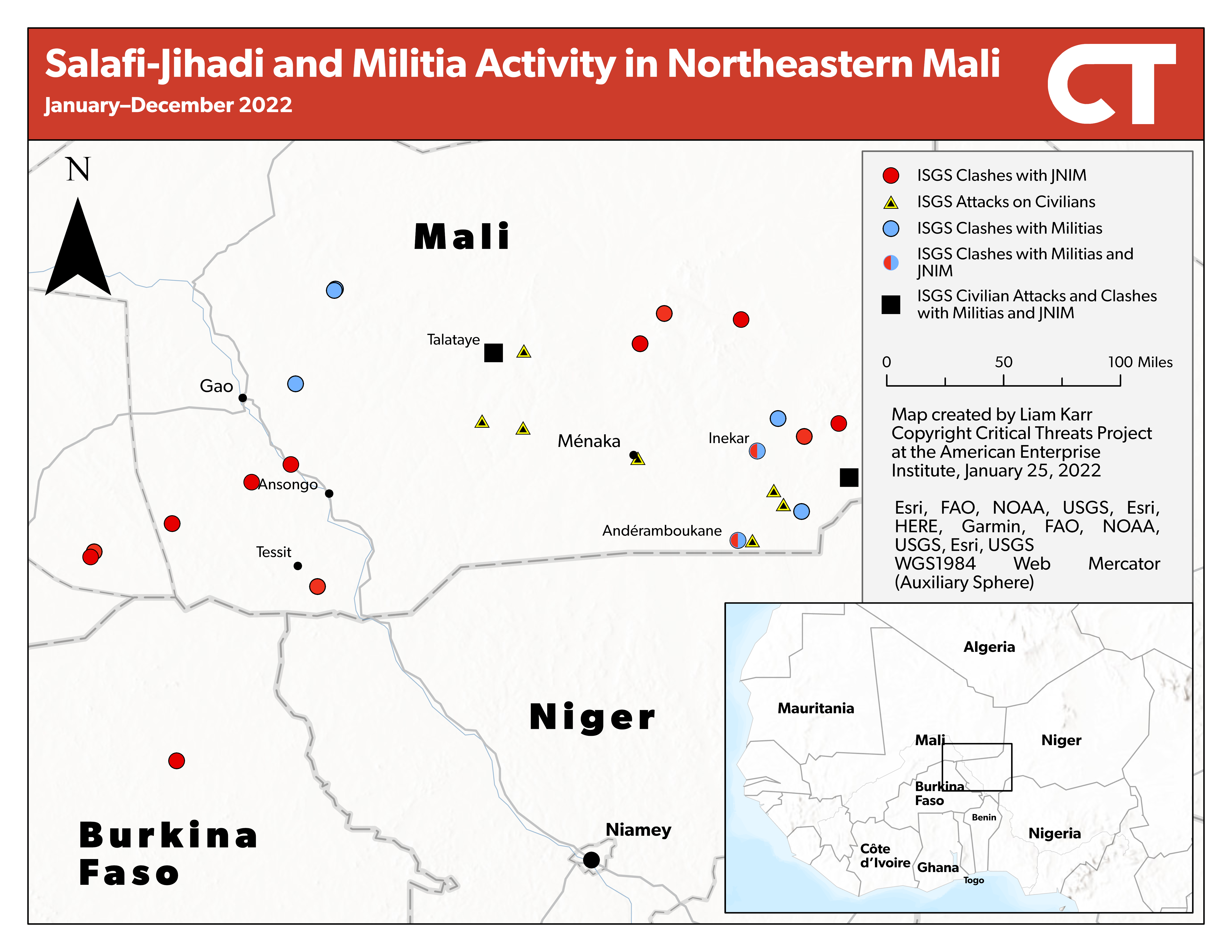

ISGS has capitalized on the lifting of counterterrorism pressure to retaliate against certain ethnic groups and expand its area of operations farther north of the Nigerien border. ISGS has regularly attacked Daoussak Tuareg communities for several years, which led Daoussak militias to partner with French forces in counter-ISGS operations. The French drawdown left these communities without a security partner and vulnerable to ISGS retaliation. ISGS began massacring Daoussak villages and expanding farther north of its typical sphere of influence throughout 2022.

The French withdrawal and its aftershocks have also affected other northern Malian actors with links to JNIM. There are several armed Tuareg groups in northern Mali, most of which fall into three general camps: Salafi-jihadi militants, former pro-separatist rebels, and pro-unionist armed groups. Many of these groups and their leaders have a decades-long history of shared human networks.[2] The Salafi-jihadi groups and pro-separatist groups initially fought on the same side of the northern Mali rebellion in 2012, before the French-led intervention in 2013 helped split the non-jihadist rebels from ag Ghali’s Ansar al Din group. The international community then facilitated an agreement between the various Tuareg rebels and the Malian government in 2015, which remains largely unimplemented. However, ag Ghali has retained contact with the former rebel networks despite their formal distancing.

Dissatisfaction among former pro-separatist rebels has increased with the departure of French forces and the Malian state’s continued absence from northern Mali. Leaders of the pro-separatist factions warned the Malian government that they felt the government was abandoning northern Mali and the 2015 peace agreement as early as July 2022. These leaders escalated by condemning the government’s lack of commitment to the agreement in December 2022 before suspending their participation in the agreement’s monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. The situation has continued to deteriorate in 2023, as the former separatist rebels *withdrew from the Malian constitutional process in January and *left a February meeting with international supporters without consensus on a path forward. The various factions within the pro-separatist movement signed a unification agreement on February 8, indicating that they may be setting conditions to revive their separatist ambitions and even attempt to *carve out an independent state.

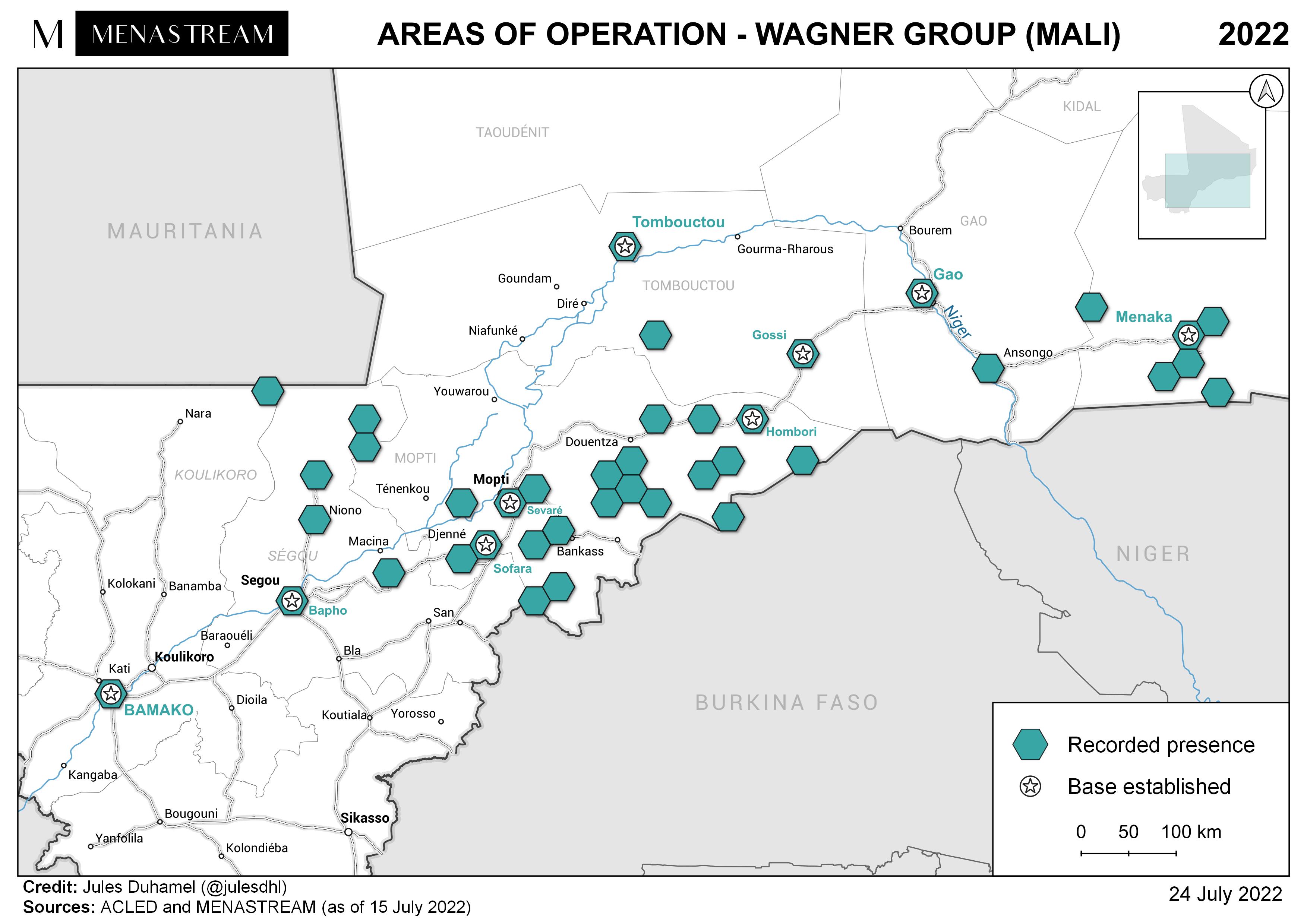

The Malian junta has attempted to compensate for its lack of capacity by hiring Kremlin-linked Wagner Group mercenaries, whose presence has increased violence against civilians to the benefit of Salafi-jihadi militants. Wagner Group mercenaries have directly contributed to the spike in violence against civilians and emboldened Malian forces and officials to disregard human rights concerns since their arrival in 2021. Wagner’s atrocities include several collective punishment massacres under the guise of counterterrorism operations that the UN and other human rights experts say amount to crimes against humanity. Wagner’s primary areas of operation have been in central Mali, but the group also has taken over former French bases in major northern towns such as Gao, Ménaka, and Timbuktu (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Areas of Operation—Wagner Group (Mali)

Source: Jules Duhamel, using data from Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project and Menastream.

JNIM is taking advantage of the deteriorating situation to cultivate partnerships with former rebels and their communities as their only viable protector. JNIM quickly moved to present itself as a security partner and strengthen its ties with Daoussak communities as ISGS attacks approached traditionally JNIM-dominated areas of Ménaka in mid-2022. JNIM and the pro-unionist Daoussak militia groups eventually launched likely coordinated offensives into ISGS-dominated parts of Ménaka (Figure 2). This relationship has continued to deepen. Several Daoussak leaders from Ménaka personally pledged allegiance to JNIM and ag Ghali following January 2023 meetings, formalizing JNIM’s partnership with some Daoussak communities. Ag Ghali also proposed a nonaggression and anti-ISGS pact in meetings with Tuareg leaders in Kidal on January 26, even though ISGS has not yet attacked there.

Figure 2. Salafi-Jihadi Activity and Militia Activity in Northeastern Mali

Source: Liam Karr.

JNIM is also taking on a protector role for northern communities fearing Malian army and Wagner Group violence. JNIM media regularly highlights its attacks on Wagner personnel to pose as a local protector and increase recruitment. Ag Ghali personally promised to protect communities from Wagner and the Malian army in recent meetings with local leaders in northern Mali, despite the limited presence of both forces in the area. The pro-separatist factions have also condemned Wagner’s deployment in Mali.

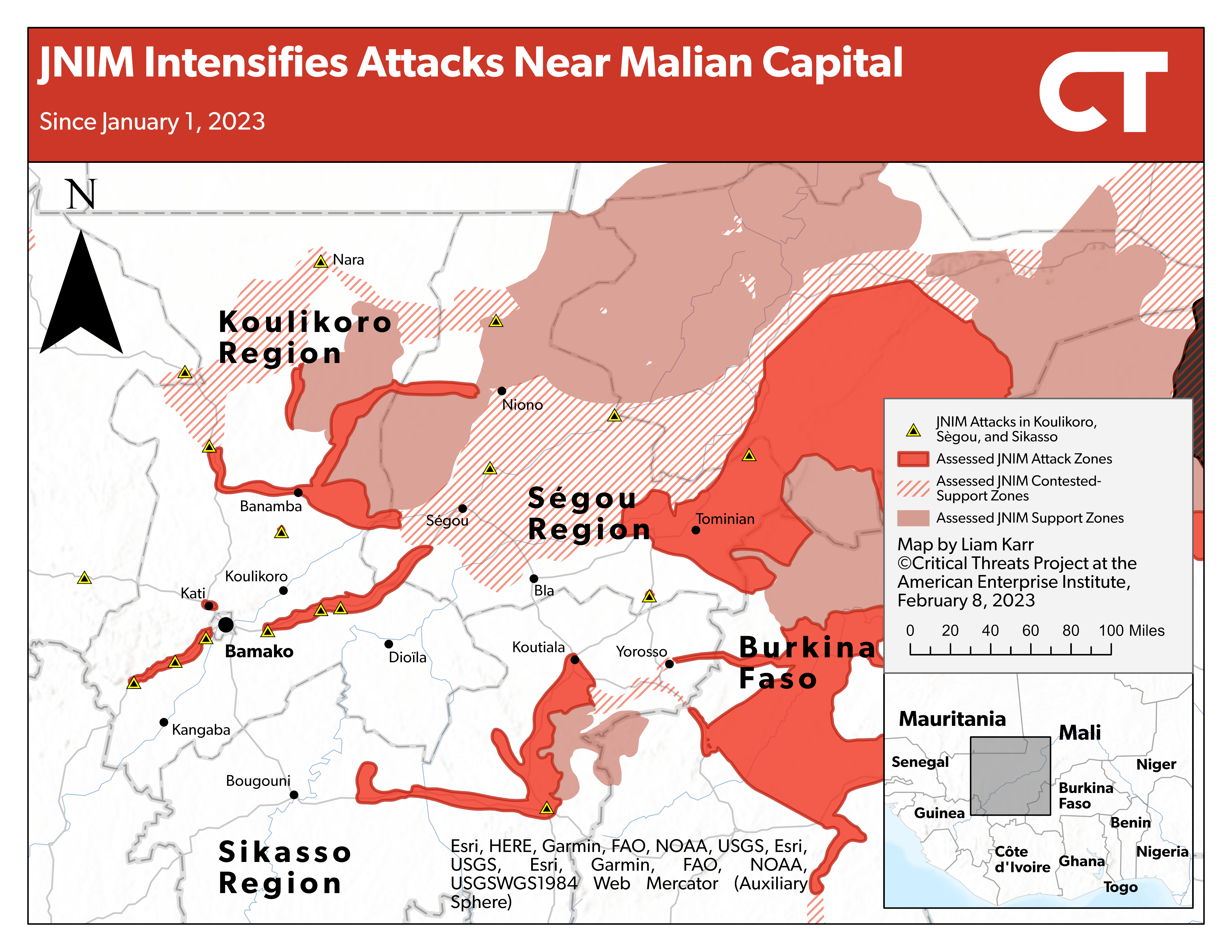

JNIM has simultaneously increased pressure on central and southern Mali, in a likely effort to preoccupy or even destabilize the Malian junta. JNIM has increased the rate and scale of attacks on security installations around Mali’s capital Bamako in the past year. The group carried out near-simultaneous vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) attacks targeting three bases across southern Mali in April 2022, attacked the main Malian army base in southern Mali with another VBIED in June 2022, and began escalating attacks around the capital in January 2023 (Figure 3). These attacks in more politically sensitive areas preoccupy the Malian junta because they are a greater threat to its legitimacy. The military takeover in 2021 stemmed in part from frustration with the previous governments’ inability to contain the JNIM and ISGS insurgencies.

Figure 3. JNIM Intensifies Attacks Near Malian Capital

Source: Liam Karr.

The multifront effort highlights the alignment between JNIM’s subsidiaries. JNIM formed as the merger of four Salafi-jihadi groups with different areas of geographic focus. The subgroup behind the southern offensive is likely the Macina Liberation Front (MLF), which is based in central Mali. Ansar al Din, which Iyad ag Ghali founded, is the active JNIM subgroup in northern Mali. The MLF and Ansar al Din are heavily connected, however. The MLF’s founder was a disciple of Iyad ag Ghali, many of its longtime members fought under Ansar al Din in the 2012 rebellion, and the group initially described itself as Ansar al Din’s “Fulani branch” in 2016, referring to its recruitment among the Fulani ethnic group. The MLF’s offensive has complemented Ansar al Din’s efforts in multiple ways and has helped distract the Malian government from JNIM’s advances in the north. JNIM media has also highlighted the MLF’s attacks in the south as another challenge to the Malian government.[3]

JNIM’s growing partnerships in northern Mali will likely result in the group exerting significant political and military control over the area. JNIM is quickly emerging as the primary power broker in the north. Northern communities will likely have no alternative but to continue some form of cooperation with JNIM, even if the short-term ISGS or Wagner threats subside. The differences and rivalries between JNIM and the various Tuareg factions will likely limit their cooperation, but the fissures between pro-unionist and pro-separatist groups will likely prevent any potential anti-JNIM front without an external driver. JNIM’s influence will likely extend to urban areas of northern Mali for the first time since 2013 in this scenario.

MINUSMA’s presence has been crucial to securing population centers across northern Mali and has helped facilitate what limited central governance and implementation of the 2015 agreement has occurred. The Malian junta has repeatedly undermined MINUSMA, however, which will likely eventually lead the mission’s withdrawal, allowing JNIM free access to urban centers. A collapse of the 2015 agreement would also most likely force a MINUSMA withdrawal and cause a similar outcome.

JNIM would likely use sanctuaries in northern Mali to strengthen its campaign to undermine the Malian government in central and southern Mali. The group will likely be able to use the north as a testing ground for more sophisticated capabilities. It has already begun deploying new technology and tactics against ISGS, such as armored VBIEDs and in-battle drone assistance. JNIM would likely be able to divert these new capabilities and additional resources to support efforts like the MLF’s ongoing campaign in southern Mali with its northern theater secured. These capability boosts would enable JNIM to carry out sophisticated attacks in the south—like its April 2022 VBIED wave—more regularly. The group could also turn these capabilities toward urban areas. It *threatened to target population centers in April 2022 and may have plotted an attack in Bamako in late April. An uptick in attacks in these politically sensitive areas would increasingly undermine the Malian junta’s legitimacy and destabilize the country.

A JNIM-controlled northern Mali may also become a haven for cells plotting transnational terror attacks. In a long-term worst-case scenario, JNIM could use these havens to cultivate transnational attack capabilities. Past patterns show that groups can rapidly pivot from local to transnational aims and that numerous factors push local groups to pursue or support transnational attacks. JNIM will likely not pursue transnational attacks in the short term, but the group has continued to encourage global attacks and never disavowed external terror attack plotting.

In a more likely scenario, JNIM will use northern Mali to support al Qaeda’s activities in neighboring regions, such as the Gulf of Guinea or North African states. JNIM-linked militants are increasingly active in the Gulf of Guinea, and the group may look to increase its efforts to capitalize on local grievances in the northern regions of these countries. JNIM also remains an affiliate of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and has incorporated some former AQIM elements into its coalition. These links would likely lead it to support or even facilitate future al Qaeda–linked efforts to capitalize on any opportunities that arise from instability in North Africa.

[1] SITE Intelligence Group, “JNIM Photo Report Displays Local Malian Tribes Pledging Allegiance to Group in Ménaka,” January 23, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com

[2] Alexander Thurston, Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local Politics and Rebel Groups (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 107, 110, 114, 118, and 130.

[3] SITE Intelligence Group, “JNIM Claims Attack on Malian Gendarmerie Post in Sikasso, Warns ‘Dark Days’ Coming upon Government and Security Forces,” February 4, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; SITE Intelligence Group, “JNIM Claims 5 Attacks in South-Central Mali, Remarks FAMa Only Bold When Fighting Civilians,” February 4, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com