More Protests, No Progress: the 2018 Iran Protests

Key Findings

The protests don't threaten the regime now, but they might someday

Although the Iranian protest movement does not remotely threaten the regime, an evolved protest scene will undoubtedly shorten the life span of the Islamic Republic

Protesters are not unified under a nationwide movement

Economic problems, government mismanagement, and ethnic, labor, sectarian, and environmental issues have driven distinct and overlapping demonstrations, but they have not cohered into a unified protest movement capable of overthrowing the regime

The protest scene evolved and became more complex in 2018

Iran’s protest scene is evolving and has become more complex and demographically encompassing since the late-December 2017 widespread riots known as the Dey Protests

Introduction

The Iranian protest movement does not remotely threaten the regime, despite its dramatic expansion this year. The protesters cannot challenge the regime’s security forces until they become more organized, acquire weapons, and garner more support among the middle class and security forces. Defections from the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and the Basij Resistance Organization are a crucial—and thus far absent—indicator that regime survival is seriously at risk. However, the potential for this protest movement to evolve into a threat is real, particularly as reimposed US sanctions begin to bite. The regime’s future depends on whether Iranians become willing to risk and lose their lives in large numbers to protest their governments’ policies. It is still too soon to tell.

As predicted, Iran’s protest scene has become more complex and demographically encompassing since the late-December 2017 widespread riots known as the Dey Protests.[1] Many different protest movements with varying objectives have spread across Iran since then (Figure 1). Economic problems, government mismanagement, and ethnic, labor, sectarian, and environmental issues have driven distinct and overlapping demonstrations. These protests have not, however, cohered into a unified movement against the regime.

Protests have been disorganized, unarmed, and generally short-lived. The largest and most violent protests were spontaneous, lacking organization and direction. Protesters are also overwhelmingly reluctant to risk their lives during violent protests and have succumbed to police pressure with relatively few casualties.

No central leadership controls when, where, or over what issues demonstrations occur; how long they last; or what the protesters do. A limited semblance of organization sometimes emerges after the beginning of many protests. Popular social media channels, many of which are run by anti-regime groups based outside Iran, post protest locations and times.[2] However, these posts have limited effect, and the channels’ organizers are disconnected from on-the-ground protesters.

This lack of coordination contrasts with the massive Iranian Green Movement protests after the fraudulent 2009 elections. The 2009 protests lasted long enough for organization to develop organically, whereas 2018 protests lasted mere days between periods of inactivity. Activists also rallied around then-presidential candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi in 2009, but no such figurehead exists in 2018.

The 2009 protesters were also ahead of the regime in digital communications,[3] but the government has since studied protesters’ communication methods and cracked down on social media without inflaming larger portions of the population. The regime’s ban of Viber after the 2009 protests and the spring 2018 ban of Telegram severely hindered protest organization.[4] Regime security forces have also cut off telephone lines, deployed jammers, and temporarily banned popular social media applications such as Instagram.[5] Bans on Instagram and WhatsApp may become permanent.[6] These bans might spur additional protests as the government stymies Iranians’ civil liberties and freedom of communication—but will make it harder for those protests to become organized.

On the other hand, this lack of organization could pose a long-term threat. Disorganized protests make predicting future flare-ups difficult. There are also no leaders for the regime to target and thus weaken the movement. Protest movements will therefore burn slowly and could explode without warning.

The regime understands that more violent protests will inevitably occur, and security forces are girding for a fight with their own people. The Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL) has equipped local police with armored vehicles and heavy weaponry. Parliament increased the Law Enforcement Forces’ (LEF) current Persian calendar year budget by over 200 percent, including a 400 percent increase for weapons and armaments following the 2018 Dey Protests.[7] The MODAFL delivered 12 unmanned aerial vehicles and six helicopters to the LEF on October 9, making good on a March 2018 cooperative agreement to equip the LEF with high-end military equipment.[8] The regime may continue militarizing its police during the current Persian calendar year.

However, current trends and disparate reports are promising for Iran’s protest scene. Social media channels unveiling the identities of officials involved in protest suppression have become more popular with tens of thousands of followers. Groups such as Rasuyab (“weasel finder”) frequently disseminate the personal information of IRGC officials, Basij members, and plain-clothes officers.[9] Private information such as cell phone numbers, addresses, and social media profiles are publicized so that protesters can defame and publicly shame regime officials.

Iranian protests will continue. The regime’s neglect of its people and inability to address protester grievances will fuel future demonstrations. This ultimately bodes ill for regime security. The reimposition of US sanctions lifted under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) places additional pressure on Iran’s heavily stressed economy. Iranian political leadership, especially those close to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the IRGC, have weaponized worsening economic protests to attack reformists and politically destroy President Hassan Rouhani.[10]

These attacks on Rouhani and his policies will prove self-defeating. Reformists support financial reforms to reintegrate Iran into the global international community, reduce government and IRGC control of the economy, create transparency, and generally create a functioning, undistorted market in Iran. These are the only economic policies likely to improve or even stabilize economic conditions.

High unemployment and inflation rates have only worsened since the May 8 US withdrawal from the JCPOA and reimplemented sanctions.[11] The Iranian rial has devalued from 35,000 rials to the dollar in September 2017 to roughly 130,000 today.[12] Most wages and salaries have not increased at the same pace against the rial’s plummeting value and growing inflation rates.[13] Protests will therefore persist and likely expand.

Regime hard-liners will gain only a limited reprieve by their attempts to redirect popular anger against the US and Rouhani. Their own policies of empowering the IRGC economically, pursuing autarky, and hoping to replace Western economic interactions with agreements with China, Russia, and third world countries will fail, significantly increasing the basis for popular grievances over time while making themselves the only ones the people have left to blame.

The Critical Threats Project (CTP) at the American Enterprise Institute has analyzed social media posts and videos from major protest movements since the Dey Protests. The most noteworthy protests are detailed below. CTP will continue to closely follow Iran’s turbulent protest scene and offer analysis as it evolves.

Notes

[1] Mike Saidi, “Iranian Anti-Regime Protests and Security Flaws: A Dataset,” Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, January 12, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/2017-2018-iranian-anti-regime-protests-and-security-flaws-a-dataset.

[2] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, August 2, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/19640.

[3] For example, protesters sent mass text messages to Tehran cell phone users during the Iranian Green Movement. See Golnaz Esfandiari, “The Twitter Devolution,” Foreign Policy, June 8, 2010, https://foreignpolicy.com/2010/06/08/the-twitter-devolution/.

[4] Entekhab, “Viber ham belakhareh filter shod” [Viber has finally been blocked too], May 14, 2014, http://www.entekhab.ir/fa/news/161368; and Mizan Online, “Dastour-e Ghazaayi-e dar khoosoos-e masdood saazi-e payaam resaan-e Telegram saader shod” [Judiciary order was issued regarding the blocking of the Telegram messenger], April 30, 2018, www.mizanonline.com/fa/news/416168.

[5] Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), “Masdood kardan-e Telegram va Instagram maghtaee ast. Ehtemaalan jomeh-ye een hafteh rafe-e ensedaad me shavad” [Telegram and Instagram’s block is temporary. The block will likely be removed Friday of this week], January 3, 2018, http://www.irna.ir/fa/News/82784430.

[6] Mike Saidi, “Iranian Regime Officials Prepare to Ban Telegram,” Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, April 25, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/threat-update/iranian-regime-officials-prepare-to-ban-telegram.

[7] Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Iran News Round Up,” March 27, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/iran-news-round-up/iran-news-round-up-march-27-2018.

[8] Tasnim News Agency, “Vezaarat-e Defaa 12 farvand-e pahpaad va 6 farvand-e baalgard beh nirouy-e entezami tahveel daad” [The Ministry of Defense delivered 12 drones and six helicopters to the Law Enforcement Forces], October 8, 2017, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1397/07/16/1847844; and Tasnim News Agency, “Emzaay-e tafaahom nameh-ye hamkaaree beyn-e vezaarat-e defaa va nirouy-e entezami” [Ministry of Defense and Law Enforcement Forces sign a cooperative agreement], March 3, 2018, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1396/12/12/1670919.

[9] Rasuyab, Telegram channel, https://t.me/rasuyab.

[10] Mike Saidi, “Iran’s Hardliners Are Going After the Entire Rouhani Administration,” Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, August 28, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/irans-hardliners-are-going-after-the-entire-rouhani-administration.

[11] International Monetary Fund, “Chapter 1: Global Prospects and Policies,” in World Economic Outlook: Challenges to Steady Growth, October 2018, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Iss-ues/2018/09/24/world-economic-outlook-october-2018.

[12] Radio Farda, “Rial Problems,” August 17, 2018, https://en.radiofarda.com/a/rial-problems/29438780.html; Bonbast, https://www.bonbast.com/; and Reuters, “As Iran Rial Hits Record Low, Police Crack Down on Money Changers,” February 14, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-economy-rial/as-iran-rial-hits-record-low-police-crack-down-on-moneychangers-idUSKCN1FY1YJ?il=0.

[13] Alef, “Joziyaati az afzaayesh-e mojaddad hooghoogh-e kaarkonaan dar saal-e jaary” [Details on the renewed increase to workers’ wages in the current year], August 23, 2018, https://www.alef.ir/news/3970616124.html.

Economic Protests

Merchant-Class Protests in Tehran. Iranian merchants, colloquially referred to as bazaaris, in Tehran staged the most high-profile and effective demonstrations since the Dey Protests. The Tehran bazaari protests, which briefly spread to other large cities such as Esfahan and Shiraz, resulted in political change, including the removal of five Rouhani administration officials since July 2018.[14] The nature of that change resulted partly from the disillusionment of the bazaari class with Rouhani and the reformist political grouping and partly from the effectiveness of hard-line politicians in channeling protest pressure in their favor.

Tehran’s protests erupted after the Iranian rial plummeted to an all-time low of 90,000 rial on June 24. Shopkeepers took to the streets. The first shops to close were in the working-class cell phone and electronic plazas in downtown Tehran. The tightly packed Charsou and Aladdin shopping malls—teeming with shopkeepers closely monitoring the rial’s value and whose livelihoods depend on the stable prices of imported goods—closed their shops and filled the streets.[15] Protesters, by unconfirmed estimates numbering 20,000, marched toward the parliament building in downtown Tehran (Figure 2).[16]

Tehran’s LEF soon intervened and confronted protesters approaching the parliament building. Protesters attempted to destroy public property and fight police, despite the LEF’s heavy presence. Many protesters threw rocks at police. Social media accounts showed videos of dump trucks intentionally unloading rocks in the streets for protesters to throw.[17] Protesters set fire to at least two police kiosks.[18] One report claimed that protesters used knives and a net to fight with police forces.[19] LEF anti-riot forces employed tear gas and paintballs to disperse and control the large crowds.[20]

The Tehran bazaari protests soon fizzled. Tehran and other major Iranian cities experienced similar economically focused protests throughout the summer after other dips in the rial’s value.[21] Similar protests will likely continue as the rial devalues further.

Hard-liners used the protests to renew their attacks against Rouhani and members of his “economic team” over long-standing and systemic financial disagreements.[22] Hard-line parliamentarians have led a campaign to interpellate senior Rouhani administration officials and have impeached Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare Minister Ali Rabiei and Economic Affairs and Finance Minister Masoud Karbasian.[23] Hard-liners also drove the removal of former Central Bank of Iran Gov. Valiollah Seif and the nominal resignation as government spokesman of Rouhani’s close ally, Mohammad Bagher Nobakht.[24]

Hard-liners also moved against other high-profile administration officials including First Vice President Eshagh Jahangiri and even Rouhani himself.[25] Parliamentarians questioned Rouhani during a plenary session on August 28 and expressed overwhelming dissatisfaction with Rouhani’s handling of the economy.[26] However, Rouhani’s questioning failed to engender a formal parliamentary interpellation hearing or his impeachment, despite hard-liner efforts.

The Tehran bazaari protests also resulted in powerful responses from Iranian celebrities. Sirvan Khosravi, a famous Iranian pop star, canceled a concert amid hearing news of the Tehran protests.[27] Khosravi, who has over 1.8 million followers on Instagram, is one of a handful of Iranian pop artists in the Islamic Republic who has received a work permit from the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance.[28] Khosravi said following the bazaari protests that “when all the business have closed down and shut down their businesses and the breadwinners don’t bring home anything other than shame, then I will cancel my concert.”

The bazaari protests rightly received much attention in the Iran analytical community because they mobilized a large swath of Iran’s commercial class, which played a key role during the 1979 Islamic Revolution.[29] Iranian merchants supported late Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and mobilized against the US-backed Shah during the revolution. Bazaaris are traditionally politically conservative but pragmatically support sound fiscal policies over ideology. A renewal of massive, anti-regime protests would greatly benefit from bazaari participation and could threaten one of the Islamic Republic’s major economic arteries.

Widespread Trucker Strikes. The trucker strikes in the of summer of 2018 were the most geographically ubiquitous of the Iranian protest movements in the past year, far surpassing the extent of the late-December 2017 Dey Protests (Figure 3).[30] The trucker strikes were also arguably the most threatening to the regime of the 2018 protest movements, especially compared with other labor-related movements. Their widespread nature, duration, and effect on dependent industries threatened vital economic trade and business. The strikes also exhibited a level of organization and deliberation that other protest movements failed to copy.

Thousands of Iranian truck drivers went on strike starting on May 21 in over 240 different towns and cities.[31] Truckers cited concerns over expensive costs for spare parts, low fares, poor insurance benefits, and high fuel costs.[32] The trucker strikes mostly subsided within weeks but still continued, albeit on a smaller scale.

Social media videos showed hundreds of truck drivers refusing to transport goods and parking their empty semis on the side of highways. The trucker strikes are also noteworthy because they spurred similar strikes among transportation-focused guilds—namely, bus and taxi drivers.[33] Regime officials agreed to raise truckers’ fares by 20 percent.[34] Truck drivers dismissed the offer and called for a raise of at least 35 percent.[35]

Trucker strikes became so serious that several large businesses and industrial centers—such as the mines in Mahallat, Markazi Province, and transportation companies in Tehran and Qazvin—shut down for several days (Figure 4).[36] Widespread videos on social media also highlighted the impact on fuel availability around the country because truckers refused to haul goods.[37]

Hundreds of vehicles would line up for gas due to the scarcity resulting from truckers refusing to make shipments.[38] Truckers, in some instances, coerced fellow truckers to join the movement, sometimes resorting to violence and threats.[39] This violence prompted police to begin escorting vehicles, primarily fuel-carrying semis, to ensure key goods were delivered without being subject to trucker violence.[40]

A recent round of widespread trucker strikes renewed on September 22, with truckers largely citing the same grievances.[41] The manager of the Imam Khomeini Port transportation terminal in Khuzestan Province noted that only 300 trucks were operating, when the normal daily average is over 2,000.[42] Truckers reportedly called for a 70 percent increase in fares.[43] Judiciary spokesperson Hojjat ol Eslam Gholam Hossein Ejei announced that “stern punishments” await those who use violence and weapons to disrupt the transportation of goods.[44] Fars Province Prosecutor General Ali al Ghasi Mehr stated that police arrested 35 protesters in Fars Province. Al Ghasi also admonished protesters that they can later be prosecuted and charged with “spreading corruption on Earth,” an indictment that carries the death sentence in Iran.[45]

Regime attempts to punish protesters by detaining them, withholding pay, and potentially executing them will likely dissuade protesters from future strikes for a time. But these actions will not appease truckers’ demands. The continuation of trucker strikes, and the expansion of labor-related protests across Iranian industries, threaten the movement of key goods and could potentially spark ancillary protests.

Notes

[14] Eterazebazar, Telegram post, June 27, 2018, https://t.me/Eterazebazar/2108; and Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Iran News Round Up,” August 24, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/iran-news-round-up/iran-news-round-up-august-24-2018.

[15] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 24, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/15938; and Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 24, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/15925.

[16] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 25, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16113; and Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 25, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16057.

[17] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 25, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16076.

[18] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 25, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16071.

[19] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 26, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16303.

[20] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 25, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16030; Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 27, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16497; and Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 26, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16379.

[21] Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Iran News Round Up,” August 6, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/iran-news-round-up/iran-news-round-up-august-6-2018.

[22] Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Iran News Round Up,” June 29, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/iran-news-round-up/iran-news-round-up-june-29-2018.

[23] Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) News Agency, “Baa 129 raey-e moaafegh; esteezaah-e Rabiei raey aavard” [With 129 votes for; Rabiei’s impeachment got passed], August 8, 2018, http://www.iribnews.ir/fa/news/2197380; and Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting News Agency, “Karbasian az vezaarat-e eghtesaad barkenaar shod” [Karbasian was dismissed from the Economic and Financial Affairs Ministry], August 26, 2018, http://www.iribnews.ir/fa/news/2212325.

[24] Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Iran News Round Up,” July 26, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/iran-news-round-up/iran-news-roundup-july-26-2018. The US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control designated Seif as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist in May 2018 for securing illicit funds and capital for the IRGC Quds Force. For more information, see US Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Targets Iran’s Central Bank Governor and an Iraqi Bank Moving Millions of Dollars for IRGC–Qods Force,” press release, May 15, 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0385; and Donya-e Eqtesad, “Estefaay-e Nobakht az maghaam-e sokhangouy-e dolat” [Nobakht’s resignation from the position of government spokesperson], August 1, 2018, https://donya-e-eqtesad.com/%D8%A8%D8%AE%D8%B4-%D8%AE%D8%A8%D8%B1-64/3421264-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%B9%D9%81%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D9%86%D9%88%D8%A8%D8%AE%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D8%B2-%D9%85%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%B3%D8%AE%D9%86%DA%AF%D9%88%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%84%D8%AA.

[25] Alef, “Hajji Babaei: raees-e team-e eghtesaady-e keshvar yani moaaven-e avval baayad javaabgou baashad” [Hajji Babaei: The head of the nation’s economic team meaning Jahangiri needs to be accountable], August 16, 2018, https://www.alef.ir/news/3970525032.html.

[26] Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, “Iran Parliament Censures Rouhani in Sign Pragmatists Losing Sway,” Reuters, August 28, 2018, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-iran-economy-rouhani/rouhani-vows-to-defeat-anti-iranian-officials-in-the-white-house-idUKKCN1LD0AC.

[27] Sirvankhosravi, Instagram post, June 25, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bkc7A66ArXm/?hl=en&taken-by=sirvankhosravi.

[28] Sirvankhosravi, Instagram channel, https://www.instagram.com/sirvankhosravi/.

[29] Kevan Harris, “The Bazaar,” in The Iran Primer, ed. Robin Wright (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2010), https://iranprimer.usip.org/resource/bazaar.

[30] Mike Saidi and Dan Amir, “A Comprehensive Look at the Iranian Anti-Regime Protests,” Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, February 22, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/a-comprehensive-look-at-the-iranian-anti-regime-protests.

[31] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, May 28, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/14040.

[32] BBC Persian, “Etesaab-e saraasari-e kamyondaar haa dar Iran vaared-e dovvomin rouz shod” [The widespread trucker strikes entered their second day], May 23, 2018, http://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-44222542.

[33] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, May 31, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/14298.

[34] Iranian Labour News Agency (ILNA), “Afzaayesh-e keraayeh-e kaamyon beyn-e 15 ilaa 20 darsad” [Increase in trucker fares between 15 to 20 percent], May 24, 2018, https://www.ilna.ir/%D8%A8%D8%AE%D8%B4-%DA%A9%D8%A7%D8%B1%DA%AF%D8%B1%DB%8C-9/626245-%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B2%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B4-%DA%A9%D8%B1%D8%A7%DB%8C%D9%87-%DA%A9%D8%A7%D9%85%DB%8C%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A8%DB%8C%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%B5%D8%AF.

[35] Radio Farda, “Dahomin rouz-e etesaab-e raanandegaan-e kaamyon dar Iran” [The 10th day of Trucker strikes in Iran], May 31, 2018, https://www.radiofarda.com/a/b3-iran-truck-taxi-drivers-strike-day-10/29262175.html.

[36] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, May 26, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/13927; and Peykeiran, “Sherkat haay-e haml o naghl ostaan-e Tehran niz beh etsaabaat-e saraasari peyvastand” [Tehran Province transportation companies also joined the widespread strikes], YouTube video, May 29, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cBz_IvU_98U.

[37] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 2, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/14380.

[38] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, May 23, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/13653.

[39] Iranian Students’ News Agency (ISNA), “Raanandegaan-e motarez az taraddod-e kaamyondaaraan dar sath-e jaadeh haa jelougiri mee konand” [Protesting drivers are preventing truckers’ commutes on the street level], May 26, 2018, https://www.isna.ir/news/97030502205.

[40] Gharashmish, “Escort-e taanker-e haml o naghl tavassot-e nirouy-e entezaami Garmeh” [The escort of transportation tankers via the LEF in Garmeh], YouTube video, May 23, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uwfRcVMuioM.

[41] Eterazebazar, Telegram post, September 22, 2018, https://t.me/Eterazebazar/8435.

[42] Manotoofficial, Instagram post, September 23, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BoD4b8qBdZv/?hl=en&taken-by=manotoofficial.

[43] Manotoofficial, Instagram post, September 24, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BoGwC9jhHbZ/?hl=en&taken-by=manotoofficial.

[44] Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), “Ejei: hokm-e edaam baraay-e 3 mofsed-e eghtesaadi saader shodeh ast” [Ejei: The adjudication of three death sentences has been issued for three economic corrupters], September 30, 2018, http://www.irna.ir/fa/News/83049339.

[45] Tasnim News Agency, “Dastgeer-e 35 nafar az ekhlalgaraan-e jaadeh haay-e Fars” [The arrest of 35 disrupters of roads in Fars], September 29, 2018, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1397/07/07/1839647.

Service-Provision and Ecological Protests

Water-Related Protests in Khuzestan. Iranian Arabs in one of the Islamic Republic’s most resource-rich provinces took to the streets in the most violent protests of the summer (Figure 5). Protesters gathered on June 29 in a main city square in Khorramshahr, Khuzestan Province, over water-related issues. Demonstrators accused local officials of mismanaging crucial water resources. Protesters also complained of a lack of drinking water.[46] Khuzestan Province is subject to some of Iran’s worst droughts and dust storms.[47] Many contend that the region’s lack of water is less ecological than it is man-made.[48] Poorly implemented and extensive dam projects and government-approved water diversion programs have left many towns and villages without adequate water.[49]

The protests gained traction and turned violent in the evening of June 29. Protesters reportedly set fire to and temporarily shut down a major bridge. Khorramshahr protesters also purportedly set fire to the Iran-Iraq War Sacred Defense War Memorial.[50] This action was notable because Khorramshahr fought for the regime against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and suffered greatly in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq War. Senior regime officials, including IRGC commanders, often visit the site.[51]

Social media reports of armed protesters with AK-47s were later confirmed by hard-liner parliamentarian Javad Karimi Ghodousi.[52] Ghodousi stated that armed protesters sought to harm the regime as a part of a Saudi-led “plot” and clashed with regime security forces.[53] Initial reports claimed that at least one protester died during the evening fighting. Later it was revealed that the alleged protester death was a hoax. A local regime loyalist claimed to have died and circulated fallacious photographs on the internet.[54] The ploy may have been intended to weed out anti-regime supporters during the protest on social media for detention at a later time.

Iranian Arabs in the oil-rich city of Abadan held protests on August 31 in solidarity with the Khorramshahr protests.[55] The Khorramshahr protests also received additional attention after famous Iranian songwriter Mohsen Chavoushi released a song called “Khouzestan” in response to the water-related protests there.[56] Chavoushi described the people of Khuzestan as “oppressed” and “wronged” by the lack of rain and the dryness of the province’s Karun River. The regime later barred him from songwriting.

Water-related protests continued on July 7 in different cities in Iran, most notably in Borazjan, Bushehr Province. Protesters there gathered in one of the city’s main squares to protest the local mismanagement of water and the resulting lack thereof.[57] Disparate reports claimed that city officials cut off water to Borazjan residents on July 3.[58] Bushehr Province Water and Sewage Company Managing Director Kay Ghobad Yakideh stated that Borazjan had been receiving less than half of its allocated amount of water.[59] Borazjan parliamentarian Mohammad Bagher Saadat elucidated that the water crisis had been occurring for 55 days.[60]

Water-related protests will continue to break out because the regime is failing to remedy systemic problems. Iran’s environmental condition and water resource mismanagement will exacerbate the ongoing water crisis. This may lead to a mass migration of Iranians, potentially sparking a refugee crisis in the tens of millions in coming years.[61]

Notes

[46] Tavaana, Instagram post, June 29, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bkna4tHgFZW/?taken-by=tavaana.

[47] Freedom Messenger, “Mardom-e Khuzestan khaak tanaffos mee konand / Ahvaz 29 Dey 1396” [The people of Khuzestan are breathing in dust / Ahvaz January 19, 2018], YouTube video, January 19, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgIFFWscvps.

[48] Seth M. Siegel, “Forget the Politics. Iran Has Bigger Problems,” Washington Post, May 16, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/democracy-post/wp/2017/05/16/forget-the-politics-iran-has-bigger-problems/?utm_term=.6eb065e82b63.

[49] US Department of State, Outlaw Regime: A Chronicle of Iran’s Destructive Behavior, Iran Action Group, September 25, 2018, 42, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/286410.pdf; and Babak Dehghanpisheh, “Water Crisis Spurs Protests in Iran,” Reuters, March 29, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-security-water-crisis/water-crisis-spurs-protests-in-iran-idUSKBN1H51A5.

[50] Amadnews.official, Instagram post, June 30, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BkqgNzfFS9_/?taken-by=amadnews.official.

[51] Mashregh News Agency, “Baazdeed-e farmaandehaan arshad az baagh-e mouzeh-ye defaa-e moghaddas” [Senior commanders visit Sacred Defense Museum], December 27, 2017, https://www.mashreghnews.ir/news/813912.

[52] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, June 30, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/16844.

[53] Alef, “Bazdaasht-e 30 terrorist-e mosallah dar aashoub haay-e akheer-e Khorramshahr” [The arrest of 30 armed terrorists in the recent Khorramshahr riots], July 17, 2018, https://www.alef.ir/news/3970426061.html.

[54] Aparat, “Koshteh shodan-e Mohammad Ansari dar Khorramshahr” [Mohammad Ansari’s killing in Khorramshahr], June 30, 2018, https://www.aparat.com/v/iD9zK.

[55] Manotoofficial, Instagram post, June 30, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BkpZ1GDhGcK/?taken-by=manotoofficial.

[56] Mohsen Chavoushi, “Khouzestan,” Radio Javan, 2018, MP3, https://www.radiojavan.com/mp3s/mp3/Mohsen-Chavoshi-Khouzestan.

[57] Freedommessenger67, Instagram post, July 7, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bk8dFVTFhiC/?taken-by=freedommessenger67.

[58] Balatarin, “Tazaahoraat-e mardom-e Borazjan dar eteraaz beh bi kefaayati masoulaan-e jomhuri-e eslami” [Demonstrations of the people of Borazjan in protest over the incompetency of the Islamic Republic’s leaders], June 2018, https://www.balatarin.com/topic/2018/7/8/1018479.

[59] Balatarin, [Demonstrations].

[60] Balatarin, [Demonstrations].

[61] Arash Karami, “Iran Official Warns Water Crisis Could Lead to Mass Migration,” Al-Monitor, April 28, 2015, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/04/iran-water-crisis-mass-migration.html.

Religious, Cultural, and Political Protests

Tehran’s Gonabadi Dervish Protests. Gonabadi Dervishes, a Sufi Muslim minority group with nearly five million adherents in Iran, staged a sit-in in northern Tehran in front of a police precinct on February 19 after security officials arbitrarily arrested a fellow adherent.[62] Officials did not disclose the reason behind the detention. LEF permitted the peaceful protest to continue for several hours before mobilizing to shut it down, even though the Interior Ministry had not issued a required permit for the protest. The protests soon turned violent as LEF anti-riot forces and protesters began to engage in intense street fighting that carried on late into the night.[63]

The Gonabadi Dervish protests saw, in at least two instances, protesters use vehicles to run over police officers.[64] These actions resulted in the death of at least five security officials and injuries to at least 30.[65] Regime officials blamed the Gonabadi for the attack. The Tehran public prosecutor announced that Mohammad Salas, a Gonabadi Dervish accused of killing three officials, was put to death on June 18.[66] The circumstances and uncertainty around Salas’ execution were contentious. Many contend that Salas was not the driver at the time of the incident.[67]

The continuation of protests among non-Shi’a religious minorities in Iran poses a special challenge to the regime. Religiously focused, antidiscrimination protests may spread to other oft-targeted religious minorities, including Sunnis in western and southeastern Iran. Anti-regime groups use the detention of religious minorities in the Islamic Republic as a pretext to launch attacks against regime security forces. Pakistan-based Sunni Baloch Army of Justice kidnapped 12 Iranian security officials in southwestern Sistan and Baluchistan Province on October 16.[68] The Army of Justice issued a list of demands on October 28 and called for the “release of a large number of Baloch youngsters” from jail.[69]

Kazeroun Protests. Thousands in Kazeroun, Fars Province, gathered on April 16 to protest a legislative bill designed to divide Kazeroun County into smaller counties. Kazeroun-based parliamentarian Hossein Reza Zadeh pushed for the bill ostensibly to permit more localized administration for citizens.[70] Proponents of the bill argued Kazeroun has become too large for proper administrative governance. Opponents of the plan expressed concerns that dividing the county will destroy the community’s cultural identity.

Early reports noted that over 5,000 people gathered for protests on April 17.[71] The mid-April protests soon restarted on May 16, the first day of the holy month of Ramadan. Protesters cited a lack of follow-up from political leadership on pending legislation to divide their county. The protests quickly turned violent. The Kazeroun protests were the most deadly incident for protesters since the Dey Protests, with at least three local citizens dead.[72] Fars Province Gov. Esmaeil Tabadar only confirmed the death of one protester from the violence between protesters and regime security forces.[73]

The violence and intensity of the protests led to the deployment of reinforcement forces from Shiraz, Fars Province. Telegram and Instagram channels showed the deployment of over 40 anti-riot trucks driving toward Kazeroun to confront protesters and likely transfer detainees to an alternate site outside the city.[74] Prisons and local detention centers are common gathering locations for protesters. Reports also cited the use of advanced police weaponry to neutralize protesters, including vehicles equipped with high-powered lights designed to blind protesters.[75] At least six armored vehicles reportedly deployed toward Kazeroun after the protests, likely to reinforce local security in the event of additional violent protests.[76]

The Kazeroun protests resulted in intense street fighting between protesters and anti-riot forces.[77] Protesters set fire to police property, including two police trucks.[78] Photos submitted on various social media channels also showed that protesters injured several LEF personnel.[79] Security officials consequently instituted a curfew and blocked the city’s internet and telephone lines following the May 16 protests.[80] Protesters also set fire on May 18 to a local branch of Mehr Bank, which is tied to the Basij Organization and the IRGC.[81]

Commander IRGC Brig. Gen. Gholam Reza Jalali of the Passive Defense Organization—an Armed Forces General Staff (AFGS) organ responsible for dealing with anti-regime propaganda and “nonmilitary” threats—denied the reports of protester deaths from the Kazeroun demonstrations.[82] Jalali claimed that anti-regime organizations photoshopped images from protests in Egypt and Bahrain to sow doubt and confusion in Iranian public opinion.[83] Photos and videos from the nightly protests and funeral posters show otherwise.[84]

Notes

[62] Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, “Information About the Gonabadi Dervishes,” March 30, 2015, https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=455524&pls=1; and VOA Farsi, “Tajammo-e eteraazi daravish gonabadi dar khiyaabaan-e paasdaaraan-e Tehran/ neshastan moghaabel kalaantari” [Gonabadi Dervishes gather for protest in Tehran’s Pasdaran St. / sitting across from the police precinct], YouTube video, February 19, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ac5ELi7Ibh8.

[63] Manotoofficial, Instagram video, February 19, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BfYnx4HBtAz/?hl=en&taken-by=manotoofficial.

[64] Bbcpersian, Instagram post, February 19, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BfY0b6WDhOI/?hl=en&taken-by=bbcpersian.

[65] Young Journalist Club (YJC), “Joziyaat-e jenaayat-e daravish-e gonabadi dar khiyaaban-e paasdaaraan / shahaadat-e 3 mamour naajaa va 2 basiji” [Details of the Gonabadi Dervishes’ wrongdoing in Pasdaran St. / The martyrdom of three LEF agents and two Basijis], March 1, 2018, https://www.yjc.ir/fa/news/6445620.

[66] Young Journalist Club (YJC), “Edaam-e Mohammad Salas, aamel shahaadat 3 mamour-e naajaa” [Mohammad Salas’ execution, the one who carried out the martyrdom of three LEF agents], June 18, 2018, https://www.yjc.ir/fa/news/6445620.

[67] BBC Persian, “Mohammad Salas edaam shod” [Mohammad Salas was executed], June 18, 2018, http://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-44517462.

[68] Edelaatnews, Telegram post, October 16, 2018, https://t.me/edaalatnews/4318.

[69] Edelaatnews, Telegram post, October 20, 2018, https://t.me/edaalatnews/4388.

[70] Radio Zamaneh, “Janjaal bar sar-e taghsim-e shahrestaan-e Kazeroun dar ostaan-e Fars” [Controversy over the division Kazeroun County in Fars Province], April 17, 2018, https://www.radiozamaneh.com/391117.

[71] Bbcpersian, Instagram post, April 17, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bhq3q-VDhx4/?hl=en&taken-by=bbcpersian.

[72] Freedommessenger67, Instagram post, May 16, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi2gpSplYcO/?taken-by=freedommessenger67.

[73] Iranian Students’ News Agency (ISNA), “Ostaandaar-e Fars taeeid kard: koshteh shodan yek nafar dar tajammoaat-e Kazeroun / Ozaa taht-e control ast” [Fars Province Governor confirms: The killing of one person in the Kazeroun gatherings / The situation is under control], May 17, 2018, https://www.isna.ir/news/97022715258.

[74] Freedommessenger67, Instagram post, May 16, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi2k07OF0bC/?taken-by=freedommessenger67.

[75] Freedommessenger67, Instagram post, May 20, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi_5v5-l1-3/?taken-by=freedommessenger67.

[76] Sedaiemardom, Telegram post, July 9, 2018, https://t.me/sedaiemardom/17591.

[77] Freedommessenger67, Instagram post, May 19, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi9fvfql0nW/?taken-by=freedommessenger67.

[78] Freedommessenger67, Instagram post, May 17, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi4JBhslz9S/?taken-by=freedommessenger67.

[79] FreedoMessenger, Telegram post, May 17, 2018, https://t.me/FreedoMessenger/26694.

[80] FreedoMessenger, Telegram post, May 17, 2018, https://t.me/FreedoMessenger/26656.

[81] Bbcpersian, Instagram post, May 18, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi6q_uvD4Cd/?taken-by=bbcpersian.

[82] Khamenei_ir, Instagram post, October 29, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BpiEeljFr4i/?hl=en&taken-by=khamenei_ir.

[83] Asr-e Iran, “Sardaar Jalali: modeereeat-e afkaar-e omoumee dar haadeseh-ye Kazeroun az jens-e amaleeaat-e ravaani boud / Baa photoshop tasaaviri az noghaat-e mokhtalef-e jahaan maanand Mesr va Bahrain beh shahr haay-e Iran mortabet mee kardand” [IRGC Commander Jalali: The management of public opinion over the Kazeroun event had a psychological-operation quality to it / With the photoshopping of images, they were relating different points of the world like Egypt and Bahrain to Iranian cities], July 8, 2018, http://www.asriran.com/fa/news/619480.

[84] Freedommessenger67, Instagram post, May 19, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bi-PVW9lhq7/?taken-by=freedommessenger67.

Khuzestan’s Emergence as Crucial Flashpoint for Protests

Ahvazi Arabs Protest Ethnic Discrimination. Iranian Arabs, an oft-targeted ethnic minority in Iran, took to the streets of Ahvaz, Khuzestan Province, on March 28 after state media, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), broadcasted a controversial segment from a children’s TV show on March 22.[85] The segment included a map of Iran’s various ethnic minorities but failed to include Iranian Arabs wearing traditional Arab garb.

Protesters assembled in front of IRIB’s office and demanded an official apology from state TV. As the protests continued, protesters soon began to voice other grievances. Human Rights Activists News Agency reported that protesters complained of water issues, unemployment, and inadequate Arabic-language education and demanded the establishment of independent Arabic-language media outlets.[86] The Ahvazi Arab protests continued for weeks.

Anti-Arab Protests. Khuzestan also experienced anti-Arab protests in late September 2018. Iranians in southwestern Iran were protesting Iraqi tourists in Iran. Many Iranians accused Iraqis of pilfering local markets and using desirable exchange rates to purchase Iranian goods and products, oftentimes leaving nothing for local Iranians.[87] The emergence of anti-Arab protests in Abadan and Khorramshahr in late September may result in additional protests among Iranian Arabs in Khuzestan Province.[88]

Western observers often overlook social and ethnic grievances when examining Iran’s protest movements. Ethnic issues undoubtedly comprise a smaller share of the space. Iranian ethnic minorities in southwestern, northwestern, and southeastern Iran have for decades been targets of regime discrimination. The regime considers such secessionist movements, often led by anti-regime militant groups such as the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK) and al Ahvaziyeh, a major threat to internal security.

The continuation of ethnically motivated protests among Arabs, Kurds, and Sunni Baloch, compounded by the notoriously poor economic conditions in many minority-dominated provinces, will make anti-regime and separatist groups more attractive and could provide the groups with members it would otherwise fail to recruit. Violence along Iranian borders with Pakistan and Iraq has increased significantly since May 2017.[89] The regime must address both endemic economic and social issues to abate this emergent and ever-increasing threat.

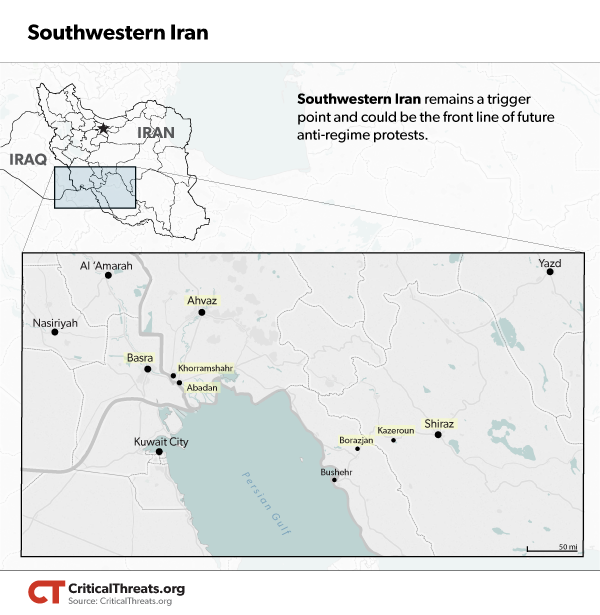

Khuzestan Province remains an especially alarming flashpoint (from the regime’s standpoint) for violent anti-regime protests. The contrast between the vast economic resources in Khuzestan and the high unemployment, poverty, drought, dust storms, and other poor living conditions make it fertile ground for demonstrations. Additionally, and most alarmingly for regime security officials, anti-regime separatist groups operate in the province, such as al Ahvaziyeh and the Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham (ISIS).

Insurgents can capitalize on the social, economic, and cultural marginalization among Iranian Arabs to recruit and attack the regime. The anti-Arab protests in Abadan and Khorramshahr in early September, along with the complementary anti-Iranian protests in Basra, Iraq, also serve as points of exploitation for radical insurgents and ISIS.[90] The recent ISIS attack in Ahvaz on an armed forces parade on September 22 supports this notion.[91] ISIS likely leveraged the porous southern border between Iran and Iraq to smuggle arms and personnel for the attack, since Khuzestan is a main smuggling point for much of Iran’s illicit drug and firearms trade.

Khuzestan remains a trigger point in Iran’s protest scene and is a dangerous nexus for the regime. Khuzestan could become a front line in any nationwide armed conflict between future protesters and regime security forces.

Notes

[85] Shabtabnews, Instagram post, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bg6ArqRgMEY/?taken-by=shabtabnews.

[86] Human Rights Activists News Agency, “Tadaavom eteraaz-e khiyaabaani sharvandaan-e Arab dar Ahvaz pas az yek hafteh / Asaamee-e baazdaasht shodegaan” [The continuation of street protests by Arab citizens in Ahvaz after one week / The names of the arrested], April 5, 2018, https://www.hra-news.org/2018/hranews/a-14799/.

[87] Asr-e Iran, “Vooroud-e Aazaad-e Iraqi haa beh Khorramshahr va Abadan / Taseeraat mosbat va manfi” [The free entry of Iraqis into Khorramshahr and Abadan / The positive and negative effects], July 22, 2018, http://www.asriran.com/fa/news/622306.

[88] Manotoofficial, Instagram post, September 7, 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BnblLUih5Zf/?hl=en&taken-by=manotoofficial.

[89] Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Threat Update,” July 24, 2018, https://www.slideshare.net/CriticalThreats/2018-0724-ctp-update-and-assessment?ref=https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/threat-update/irans-hardliners-may-call-for-the-parliamentary-questioning-of-increasingly-senior-members-of-the-rouhani-administration.

[90] Tamer El-Ghobashy and Mustafa Salim, “Chanting ‘Iran Out!’ Iraqi Protesters Torch Iranian Consulate in Basra,” Washington Post, September 7, 2018, https://wapo.st/2wVJp6S?tid=ss_tw&utm_term=.1778373d6831; and Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Iran File: ISIS and IRGC Cycle of Violence Likely to Escalate,” October 3, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/iran-file/iran-file-ISIS-and-IRGC-cycle-of-violence-likely-to-escalate.

[91] Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute, “Iran News Round Up,” September 24, 2018, https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/iran-news-round-up/iran-news-round-up-september-24-2018.

Conclusion

Iran’s protest scene remains turbulent and will continue to generate increasingly violent demonstrations. However, future protests will unlikely existentially threaten the regime in the near term. The protests detailed above never required the deployment of regular IRGC conventional or militarized Basij battalions. The deadliest protests elicited low-level IRGC and Basij involvement. For the most part, particularly in larger cities, LEF anti-riot forces and local Basij units successfully quelled protests quickly and with little bloodshed.

Iranian protests encompass many grievances and span many different kinds of issues, yet they all rapidly become political. Economic protests tend to be political and quickly devolve into anti-regime protests subsequently. Ethnic and cultural protests quickly turn political. Ongoing and political rights–focused movements such as the anti-hijab protests transformed into heavily publicized anti-regime demonstrations.[92] Iranian protests’ proclivity to adopt a political and oftentimes anti-regime tone is a worrisome indicator for the Islamic Republic.

As long as the regime continues to deprioritize Iranians’ economic well-being, use unemployment and economic turmoil for political attacks and internal power struggles, and discriminate against ethnic and religious minorities, protests will continue. Iranian leaders’ inability to implement key financial reforms and address long-standing protester grievances will lead to the intensification of protests.

However, protests are far from affecting the regime change. As Iran’s protest scene continues to evolve and potentially be hijacked by armed, openly anti-regime groups, the regime may see itself one day confronted with a movement it cannot quickly or easily suppress. The end is not near for the regime, but an evolved protest scene will undoubtedly shorten the life span of the Islamic Republic.

Notes

[92] Thomas Erdbrink, “Tired of Their Veils, Some Iranian Women Stage Rare Protests,” New York Times, January 29, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/29/world/middleeast/head-scarf-protests-iran-women.html.

About the Author

Mike Saidi is an analyst and the Iran team lead for the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute

About Our Technology Partners

The conclusions and assessments in this report do not reflect the positions of our technology partners.

Neo4j is a highly scalable native graph database that helps organizations build intelligent applications that meet today’s evolving connected data challenges including fraud detection, tax evasion, situational awareness, real-time recommendations, master data management, network security, and IT operations. Global organizations such as MITRE, Walmart, the World Economic Forum, UBS, Cisco, HP, Adidas, and Lufthansa rely on Neo4j to harness the connections in their data.

Ayasdi is on a mission to make the world’s complex data useful by automating and accelerating insight discovery. The company’s Machine Intelligence software employs Topological Data Analysis to simplify the extraction of knowledge from even the most complex data sets confronting organizations today—converting data into business impact.

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve US strategic objectives. ISW is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, public policy research organization.

Ntrepid enables organizations to safely conduct their online activities. Ntrepid’s Passages technology leverages the company’s platform and 15-year history protecting the national security community from the world’s most sophisticated opponents. From corporate identity management to secure browsing, Ntrepid products facilitate online research and data collection and eliminate the threats that come with having a workforce connected to the Internet.

Linkurious’ graph visualization software helps organizations detect and investigate insights hidden in graph data. It is used by government agencies and global companies in anti–money laundering, cybersecurity, or medical research. Linkurious makes today’s complex connected data easy to understand for analysts.

Praescient Analytics is a veteran-owned small business based in Alexandria, Virginia. Our aim is to revolutionize how the world understands information by empowering our customers with the latest analytic tools and methodologies. Currently, Praescient provides several critical services to our government and commercial clients.

AllSource uses satellites, airplanes, drones, social media, weather, news feeds, and other real time data services to deliver Geospatial Intelligence produced by advanced software and analysis.

Hanzo empowers organizations with legally defensible investigation, capture, and preservation of dynamic web content. Its powerful tools are trusted by global corporations, international nonprofits, and government agencies to provide the most efficient and confident capture from the broadest and most complex data sources.