{{currentView.title}}

June 06, 2024

2024 Iranian Presidential Election Tracker

This landing page provides context on how the Iranian election works, information about who is running, and updates on the latest developments. Follow the daily Iran Update published by the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute in partnership with the Institute for the Study of War for further analysis.

Iran will hold a snap presidential election on June 28, 2024. The election will replace Ebrahim Raisi, who died in a helicopter crash in northwestern Iran, and bring to power a new president for a four-year term. Influential factions and powerbrokers have already begun maneuvering to promote their preferred candidates in the race. The Iranian supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, and his inner circle will now begin engineering the election, as they have done in previous electoral cycles, to ensure that a loyal ideologue becomes the next president.

The role of the presidency in the Iranian political system is complex and significantly weaker than other presidential systems around the world. The supreme leader—not the president—is Iran’s ultimate political authority and commander-in-chief. The supreme leader makes most major decisions, including determining Iran’s domestic agendas and overall strategic orientation. The president conversely manages day-to-day affairs and the economy and has almost no control of the Iranian military and security apparatus.

The president is nevertheless important in that they are a figurehead for the Iranian state and advise the supreme leader on a wide range of issues. The president, for instance, serves ex officio on key policy bodies, such as the Supreme National Security Council, Supreme Economic Coordination Council, Supreme Cultural Revolution Council, and Supreme Cyberspace Council. This access allows the president to influence and shape major decisions so long as they adhere to the parameters that the supreme leader sets.

The next Iranian president is particularly important because of the role they will probably have in determining the next supreme leader. Khamenei is presently 85 years old and could very well die during the next president’s term. The president in this scenario would have opportunities to influence whichever succession candidates emerge. The president could even become a contender for succession themselves if they are a cleric. Such a move has precedent, given that Khamenei was president before becoming supreme leader in 1989.

CTP-ISW did not report on the Iranian presidential election on June 30.

Some senior IRGC commanders have emphasized in recent days the need for the Iranian political establishment, particularly hardliners, to accept and support Iranian President-elect Masoud Pezeshkian in order to preserve political stability. Former IRGC Commander Major General Mohsen Rezaei said on July 10 that Pezeshkian should be considered part of “the revolution front,” which is a reference to parts of the hardline camp.[iii] Rezaei further stated that those who support the regime and Islamic Revolution must also support Pezeshkian. IRGC Aerospace Force Commander Brigadier General Amir Ali Hajji Zadeh similarly on July 11 called on supporters of runner-up presidential candidate Saeed Jalili to respect Pezeshkian’s victory and avoid criticizing the electoral process.[iv] Hajji Zadeh described Pezeshkian as “the president of the entire nation and of every Iranian.” Hajji Zadeh also noted that former President Ebrahim Raisi’s death could have triggered a “major crisis” but that the regime averted such a crisis and conducted two rounds of voting within a week “without the smallest problem.” Rezaei’s and Hajji Zadeh’s statements are consistent with CTP-ISW's previous assessment that Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei prioritized regime legitimacy and stability over installing his preferred candidate in the election.[v]

Iranian President-elect Masoud Pezeshkian is apparently considering nominating Abbas Araghchi as his foreign affairs minister, underscoring Pezeshkian’s intent to seriously pursue nuclear negotiations with the West. IRGC-affiliated media reported on July 10 that Pezeshkian’s advisers "have almost reached the final conclusion” to nominate Araghchi, citing an unspecified source.[xiv] The source claimed that Araghchi has advised Pezeshkian on his conversations with unspecified Axis of Resistance and regional officials in recent days. Araghchi played a prominent role in the nuclear negotiations with the West under the Hassan Rouhani administration and served as Rouhani's deputy foreign affairs minister for policy between 2017 and 2021.[xv] It is unclear whether the Iranian Parliament, which is currently dominated by hardliners, would approve Araghchi as foreign affairs minister. It is furthermore unclear whether Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei would permit Araghchi to pursue nuclear negotiations with the West in a manner meaningful different from the Ebrahim Raisi administration if the Iranian Parliament does approve him as foreign affairs minister. Khamenei implicitly criticized Pezeshkian’s support for increasing Iranian engagement with the West in a speech on June 25.[xvi]

Iranian President-elect Masoud Pezeshkian appears to be associating himself with members of the moderate Hassan Rouhani administration, which was in power from 2013-21. Pezeshkian identified former Foreign Affairs Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif as one of his close advisers and supports while running for the presidency.[xi] Zarif served in the Rouhani administration and played a prominent role in negotiating the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.[xii] Rouhani’s Information and Communications Technology Minister Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi has separately been advising Pezeshkian throughout his campaign.[xiii] Pezeshkian has since winning the presidential elections met other members of the Rouhani administration, such as Rouhani himself and former Economic Affairs and Finance Minister Ali Taib Nia.[xiv] The connection between Pezeshkian and the Rouhani administration could indicate that Pezeshkian will draw from this network to build his cabinet. That Pezeshkian may be rallying support from Rouhani’s circles would be unsurprising given that Pezeshkian has not historically appeared to have a prominent support base independently. Pezeshkian will remain considerably constrained in his capacity as president, regardless of support from Rouhani and his network.

Masoud Pezeshkian held a phone call with Russian President Vladimir Putin on July 8, marking one of his first known call with a foreign official as president-elect.[xv] Pezeshkian advocated for the continued expansion of Russo-Iranian ties on the call.

Post-election statements by both President-elect Masoud Pezeshkian and the supreme leader indicate that the Pezeshkian administration will not change the regime’s trajectory. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei stated his desire for Pezeshkian to continue the policies of former president Ebrahim Raisi in a message on July 6 following the presidential election.[viii] Pezeshkian issued a statement to the people of Iran on July 6 following the election thanking Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei for opening the field for “participation and competition.”[ix] Pezeshkian has repeatedly reiterated his commitment to enforcing Khamenei’s policies throughout his campaign. Pezeshkian also prayed at the tomb of first Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini on July 6 after the election to “renew his allegiance to Khomeini’s ideals.”[x] Masoud Pezeshkian will be sworn in as the ninth president of the Islamic Republic of Iran on August 4 or 5, according to a member of Iran’s parliament presiding board.[xi]

Moderate politician Masoud Pezeshkian won the Iranian presidential runoff election on July 5.[i] Iranian media reported that Pezeshkian received over 16 million votes, while his opponent, ultraconservative hardliner Saeed Jalili, received approximately 13.5 million votes.[ii] Pezeshkian and Jalili won approximately 10.4 million and 9.5 million votes respectively in the first round of voting on June 28.[iii] The Iranian Election Headquarters announced that voter turnout in the runoff presidential election was 49.8 percent, marking an approximately 10 percent increase from the first round of elections on June 28.[iv] Pezeshkian will be inaugurated on an unspecified date between July 22 to August 5.[v]Pezeshkian’s presidency will mark a departure from hardline President Ebrahim Raisi’s presidency. Pezeshkian has repeatedly criticized Raisi’s presidency in recent weeks.[vi]

Pezeshkian previously served as a senior health official in the reformist Mohammad Khatami administration from 2000-2005 and as a parliamentarian from 2008 to 2024.[vii] Pezeshkian hails from Mahabad, West Azerbaijan Province, and is fluent in Azeri and Kurdish.[viii] Pezeshkian is trained as a physician and served as a medic during the Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988.[ix] He later served in the reformist Khatami administration as health and medical education minister.[x] Pezeshkian is currently a parliamentarian representing East Azerbaijan Province and has held this role for 16 years.[xi] He served as a deputy parliament speaker in 2016.[xii] Pezeshkian was disqualified from running in the 2021 presidential election, making his recent qualification and subsequent presidential win noteworthy.[xiii]

Pezeshkian will likely attempt to pursue nuclear negotiations with the West, although it is unclear to what extent Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei will permit him to do so. Pezeshkian called for increasing international engagement with Western actors and endorsed a return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) throughout his campaign.[xiv] Mohammad Javad Zarif, the foreign affairs minister under reformist president Hassan Rouhani who helped negotiate the JCPOA in 2015, has played a prominent role in Pezeshkian’s campaign, suggesting that Pezeshkian is committed to resuming negotiations.[xv] Pezeshkian separately supported resolving issues with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).[xvi] The FATF blacklisted Iran in February 2020 for failing to implement anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing policies.[xvii] The Supreme Leader has previously expressed foreign policy and nuclear views that promote domestic production over economic engagement with the West, making it unclear to what extent Khamenei will permit Pezeshkian to engage with Western actors.[xviii] Khamenei has also indirectly criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign and has called on him to “continue [former hardline president Ebrahim] Raisi’s path” in his presidency.[xix]

Pezeshkian’s presidency is unlikely to generate meaningful changes within the regime. Pezeshkian supports regime policies like mandatory veiling. Pezeshkian has previously critiqued the Noor Plan—a 2024 Iranian law enforcement plan that often violently enforces veiling—but continues to support mandatory veiling within Iran and has argued that the regime must reform the way it educates girls so that they do not question the need to veil.[xx] Pezeshkian has also boasted about his role in enforcing mandatory veiling in hospitals and universities shortly after the Islamic Revolution.[xxi] Pezeshkian has repeatedly reiterated his commitment to enforcing Khamenei’s policies throughout his campaign. The president also lacks the authority to pursue policies different from the supreme leader’s edicts, even if the president aims to pursue policies separate from the supreme leader.[xxii]

Pezeshkian’s presidency suggests that Khamenei prioritized the regime’s legitimacy over his individual legacy in this instance. Khamenei implicitly criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign policies and espoused Jalili’s nuclear and foreign policy views in a speech on June 25, which suggested that Khamenei preferred Jalili over Pezeshkian.[xxiii] Khamenei previously paved the way for his preferred candidate, Ebrahim Raisi, to win the August 2021 presidential election.[xxiv] The fact that Khamenei allowed Pezeshkian to win the election suggests that Khamenei prioritized preserving the Islamic Republic’s veneer as a “religious democracy” over installing a president who more closely aligns with his hardline stances on domestic and foreign issues.

It is particularly noteworthy that Khamenei allowed Pezeshkian to win given that the next Iranian president may oversee Khamenei’s succession. Khamenei is currently 85 years old and has almost certainly begun to consider who will succeed him. That Khamenei allowed Pezeshkian to win suggests that he believes Pezeshkian could maintain order in the regime and Iranian society during a potential succession crisis. It also suggests that Khamenei prioritizes regime survival over having a president in power whose views and policies directly align with his own.

Khamenei may have calculated that manipulating the July 5 election results could stoke widespread unrest. The regime previously engineered the election results between reformist Mir Hossein Mousavi and hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009, which galvanized a months-long anti-regime protest wave.[xxv] The regime might be particularly wary of public unrest given that it recently suppressed the 2022-2023 Mahsa Amini movement and that much of the Iranian population still holds sociocultural, political, and economic grievances against the regime.[xxvi]

Moderate politician Masoud Pezeshkian won the Iranian presidential runoff election on July 5.[i] Iranian media reported that Pezeshkian received over 16 million votes, while his opponent, ultraconservative hardliner Saeed Jalili, received approximately 13.5 million votes.[ii] Pezeshkian and Jalili won approximately 10.4 million and 9.5 million votes respectively in the first round of voting on June 28.[iii] The Iranian Election Headquarters announced that voter turnout in the runoff presidential election was 49.8 percent, marking an approximately 10 percent increase from the first round of elections on June 28.[iv] Pezeshkian will be inaugurated on an unspecified date between July 22 to August 5.[v]Pezeshkian’s presidency will mark a departure from hardline President Ebrahim Raisi’s presidency. Pezeshkian has repeatedly criticized Raisi’s presidency in recent weeks.[vi]

Pezeshkian previously served as a senior health official in the reformist Mohammad Khatami administration from 2000-2005 and as a parliamentarian from 2008 to 2024.[vii] Pezeshkian hails from Mahabad, West Azerbaijan Province, and is fluent in Azeri and Kurdish.[viii] Pezeshkian is trained as a physician and served as a medic during the Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988.[ix] He later served in the reformist Khatami administration as health and medical education minister.[x] Pezeshkian is currently a parliamentarian representing East Azerbaijan Province and has held this role for 16 years.[xi] He served as a deputy parliament speaker in 2016.[xii] Pezeshkian was disqualified from running in the 2021 presidential election, making his recent qualification and subsequent presidential win noteworthy.[xiii]

Pezeshkian will likely attempt to pursue nuclear negotiations with the West, although it is unclear to what extent Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei will permit him to do so. Pezeshkian called for increasing international engagement with Western actors and endorsed a return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) throughout his campaign.[xiv] Mohammad Javad Zarif, the foreign affairs minister under reformist president Hassan Rouhani who helped negotiate the JCPOA in 2015, has played a prominent role in Pezeshkian’s campaign, suggesting that Pezeshkian is committed to resuming negotiations.[xv] Pezeshkian separately supported resolving issues with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).[xvi] The FATF blacklisted Iran in February 2020 for failing to implement anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing policies.[xvii] The Supreme Leader has previously expressed foreign policy and nuclear views that promote domestic production over economic engagement with the West, making it unclear to what extent Khamenei will permit Pezeshkian to engage with Western actors.[xviii] Khamenei has also indirectly criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign and has called on him to “continue [former hardline president Ebrahim] Raisi’s path” in his presidency.[xix]

Pezeshkian’s presidency is unlikely to generate meaningful changes within the regime. Pezeshkian supports regime policies like mandatory veiling. Pezeshkian has previously critiqued the Noor Plan—a 2024 Iranian law enforcement plan that often violently enforces veiling—but continues to support mandatory veiling within Iran and has argued that the regime must reform the way it educates girls so that they do not question the need to veil.[xx] Pezeshkian has also boasted about his role in enforcing mandatory veiling in hospitals and universities shortly after the Islamic Revolution.[xxi] Pezeshkian has repeatedly reiterated his commitment to enforcing Khamenei’s policies throughout his campaign. The president also lacks the authority to pursue policies different from the supreme leader’s edicts, even if the president aims to pursue policies separate from the supreme leader.[xxii]

Pezeshkian’s presidency suggests that Khamenei prioritized the regime’s legitimacy over his individual legacy in this instance. Khamenei implicitly criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign policies and espoused Jalili’s nuclear and foreign policy views in a speech on June 25, which suggested that Khamenei preferred Jalili over Pezeshkian.[xxiii] Khamenei previously paved the way for his preferred candidate, Ebrahim Raisi, to win the August 2021 presidential election.[xxiv] The fact that Khamenei allowed Pezeshkian to win the election suggests that Khamenei prioritized preserving the Islamic Republic’s veneer as a “religious democracy” over installing a president who more closely aligns with his hardline stances on domestic and foreign issues.

It is particularly noteworthy that Khamenei allowed Pezeshkian to win given that the next Iranian president may oversee Khamenei’s succession. Khamenei is currently 85 years old and has almost certainly begun to consider who will succeed him. That Khamenei allowed Pezeshkian to win suggests that he believes Pezeshkian could maintain order in the regime and Iranian society during a potential succession crisis. It also suggests that Khamenei prioritizes regime survival over having a president in power whose views and policies directly align with his own.

Khamenei may have calculated that manipulating the July 5 election results could stoke widespread unrest. The regime previously engineered the election results between reformist Mir Hossein Mousavi and hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009, which galvanized a months-long anti-regime protest wave.[xxv] The regime might be particularly wary of public unrest given that it recently suppressed the 2022-2023 Mahsa Amini movement and that much of the Iranian population still holds sociocultural, political, and economic grievances against the regime.[xxvi]

Iran held its second round of its presidential election between ultraconservative hardliner candidate Saeed Jalili and moderate candidate Masoud Pezeshkian on July 5.[xi] The Iranian Election Headquarters extended the voting deadline from 1800 to 0000 local time, likely to try to increase voter turnout.[xii] This action is not unprecedented; the regime has previously extended voting hours during both presidential and parliamentary elections, including during the June 28 first round presidential election.[xiii] The Interior Ministry will likely announce the final election results in the morning local time of July 6. CTP-ISW will publish analysis of the results on July 6.

Recent Iranian polls show that moderate Masoud Pezeshkian is leading over ultraconservative hardliner Saeed Jalili in the Iranian presidential race.[i] The runoff election will occur on July 5. The Iranian Students Polling Agency (ISPA) published a poll on July 4 showing that Pezeshkian has a 5.6 percent lead over Jalili.[ii] ISPA notably predicted accurately that Pezeshkian and Jalili would win the highest and second highest number of votes, respectively, in the first round of voting on June 28.[iii] ISPA also correctly predicted that pragmatic hardliner Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf would receive significantly less votes than Pezeshkian and Jalili.[iv] The July 4 ISPA poll is consistent with CTP-ISW's observation on July 1 that Pezeshkian appears to be gaining momentum ahead of the July 5 runoff election.[v]

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei must decide whether he will permit Pezeshkian to win the election if Pezeshkian wins the most votes. Khamenei recently expressed foreign and nuclear policy views on June 25 that closely align with Jalili’s views, suggesting that Khamenei endorses Jalili.[vi] Khamenei furthermore indirectly criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign policies on the same date.[vii] Khamenei’s opposition to some of Pezeshkian’s policies could lead him to directly intervene in the upcoming election and install Jalili as president.

July 3

The two Iranian presidential candidates—ultraconservative Saeed Jalili and reformist Masoud Pezeshkian—discussed economic issues in their final debate before the upcoming runoff election.[i] The debate occurred on July 2. The runoff election will occur on July 5. Below are the key takeaways from what Jalili and Pezeshkian said in the debate.

- Saeed Jalili. Jalili continued to downplay the importance of nuclear negotiations with the West and relief from international sanctions in order to improve the Iranian economy. Jalili argued that Iran should instead prioritize increasing energy exports and pursuing an autarkic agenda. He also noted the importance of attracting foreign investment but did not explain how to do so without sanctions relief. Jalili separately criticized Pezeshkian’s understanding of economic issues and questioned his competence.

- Masoud Pezeshkian. Pezeshkian tried to garner support from hardliners by reiterating his subordination to the supreme leader and voicing support for some hardline policies. Pezeshkian vowed to continue implementing the Strategic Action Plan, which is a law that the hardliner-dominated Parliament passed in 2020 to increase uranium enrichment and restrict international inspectors’ access to Iranian nuclear sites. The moderate-reformist bloc has criticized the law as an obstacle to advancing nuclear negotiations with the West.

Iranian reformist presidential candidate Masoud Pezeshkian appears to be gaining momentum ahead of the runoff presidential elections on July 2. Several recent polls demonstrate that Pezeshkian is maintaining his lead over hardline candidate Saeed Jalili.[i] Pezeshkian received 10.4 million votes and Jalili received around 9.5 million during the first round of elections on June 28.[ii] Former presidential candidate and pragmatic hardliner Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf’s campaign head Sami Nazari Tarkarani also endorsed Pezeshkian on July 2.[iii] This endorsement may divert some of 3.4 million votes Ghalibaf received during the first round of elections to Pezeshkian, thus advantaging Pezeshkian.[iv] Pezeshkian also performed strongly in a July 1 economic debate against Jalili. Members of Jalili’s own faction criticized Jalili’s poor performance, in contrast.[v] Details on this debate are included in the following paragraphs.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei must determine if he will permit Pezeshkian to win the election if Pezeshkian maintains his lead over Jalili. Khamenei expressed foreign and nuclear policy views on June 25 that closely align with ultraconservative hardline presidential candidate Saeed Jalili’s views, suggesting that Khamenei endorses Jalili.[vi] Khamenei also indirectly criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign policies on the same date.[vii] This suggests that Khamenei may decide to prevent Pezeshkian from becoming president. Raisi’s 2021 election suggests that Khamenei is comfortable engineering elections to advantage his preferred candidate.[viii] The Guardian Council denied the candidacies of several prominent politicians in the 2021 elections and Raisi therefore faced no significant competition in the race.[ix]

It is unclear, however, how and if Khamenei will advantage Jalili if Pezeshkian is able to generate increased support and win the election this week. The regime engineered the election results between reformist Mir Hossein Mousavi and hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009, galvanizing a months-long anti-regime protest wave.[x] Khamenei would risk further deteriorating regime legitimacy and possibly kickstarting unrest if Pezeshkian garners increased support in the coming days and Khamenei decides to undermine Pezeshkian’s ability to win the election.

The two remaining presidential candidates, reformist Masoud Pezeshkian and hardliner Saeed Jalili, discussed the economy in the first debate of the election’s second round on July 1.[xi] Both candidates reiterated previous economic talking points on their agenda from the first round.[xii]

- Masoud Pezeshkian (reformist): Pezeshkian emphasized the importance of increased public participation in the economy, including by women and minority groups. Pezeshkian also emphasized the importance of high voter turnout rates for the final election on July 5. He probably calculates that a greater voter turnout will improve his chances at election.[xiii] Pezeshkian said that international sanctions cause Iran’s economic issues in part, but that the government’s failure to fully implement economic policy also contributes to Iran’s economic woes.[xiv] Pezeshkian said that improving the economy also requires pragmatism in diplomatic relations with the world, noting that Iran will ”never...cancel all sanctions” and that loosening sanctions depends on ”what we give [diplomatically] and what we get [diplomatically]“ and whether Iran wants to ”solve [its] problem with the world or not.”[xv] Pezeshkian also noted the value of strong management within government.

- Saeed Jalili (ultraconservative hardliner): Jalili focused on how the next government can create more employment opportunities.[xvi] Jalili agreed with Pezeshkian that greater participation in the economy is better.[xvii] Jalili proposed finding alternative trade partners to alleviate sanctions’ impact on the Iranian economy.[xviii] This suggestion presumably means that China, Russia, and other US adversaries. Jalili did not suggest returning to nuclear negotiations as a way to improve the Iranian economy or relations with foreign countries.[xix] Jalili criticized Pezeshkian for placing too much of the blame on the Iranian government for the failure of JCPOA and not enough on the other parties involved.[xx]

Hardline presidential candidate Saeed Jalili will likely win the Iranian presidential election in the runoff race on July 5. No candidate received the majority of votes needed to win the Iranian presidential election on June 28 and Iran will hold a runoff election between the two most popular candidates—ultraconservative Saeed Jalili and reformist Masoud Pezeshkian—on July 5.[i] Pezeshkian received 10.4 million votes while Jalili received around 9.5 million. The second most prominent hardline candidate—Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf—received around 3.4 million votes in the first round of elections on June 28, which was not enough to compete in the runoff election.[ii] At least some Ghalibaf voters will presumably back Jalili in the runoff election, however, giving Jalili a significant advantage over Pezeshkian. Pezeshkian has also struggled to consolidate support among Iranian youth, a key voter demographic for the reformist faction.[iii] Pezeshkian is unlikely to garner enough support to win against Jalili, especially since social media users have circulated statements in recent days of Pezeshkian boasting about his role in enforcing unpopular policies such as mandatory veiling.[iv]

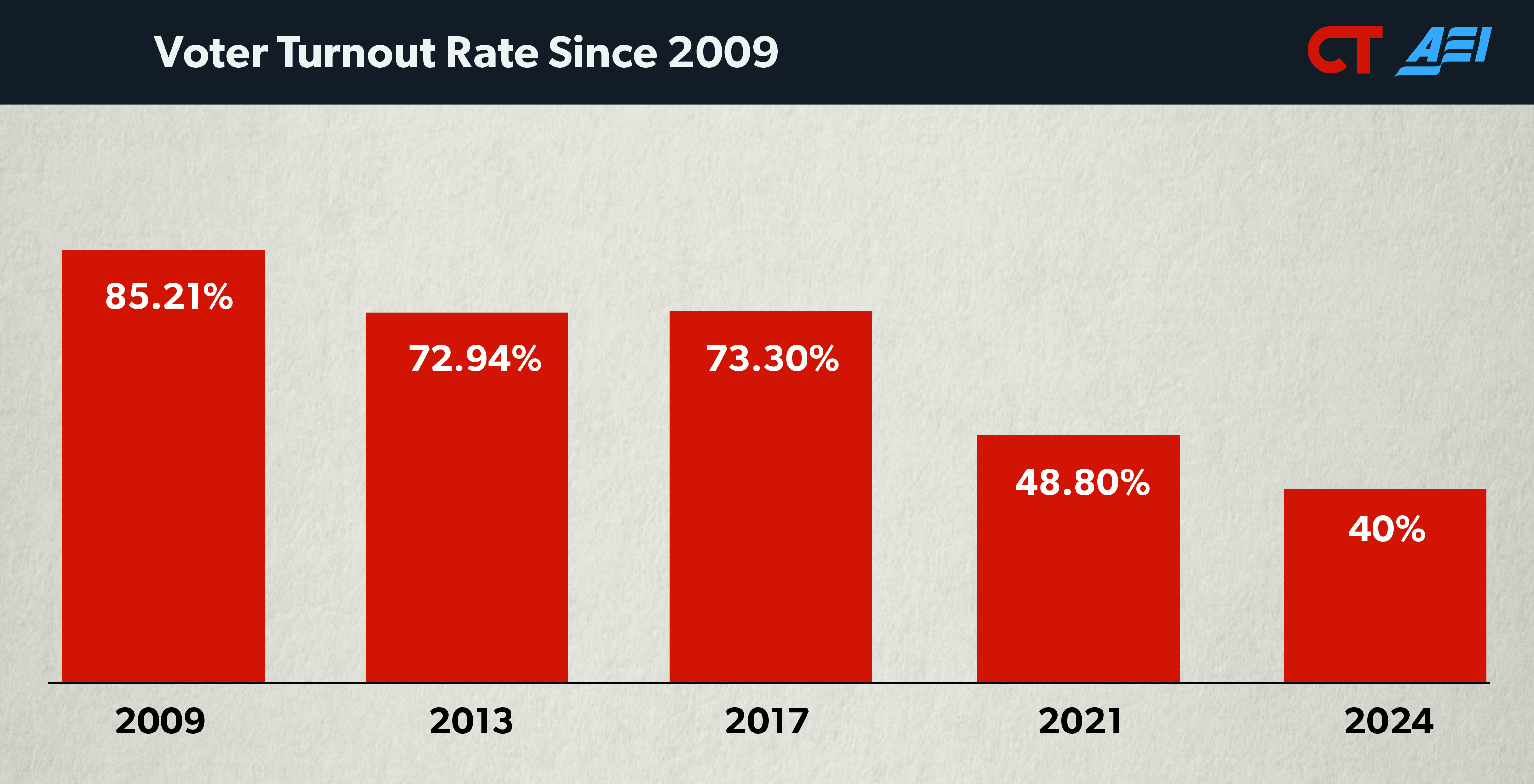

The Iranian regime is attempting to frame the July 5 presidential runoff elections as a fair and competitive race, despite Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei indicating a preference for hardline candidate Saeed Jalili. Khamenei has repeatedly expressed concern about low voter turnout rates in recent years and views participation in Iran’s presidential elections as a demonstration of Iran’s democratic legitimacy.[v] Iranian regime officials during this election cycle have attempted to reinforce the regime’s democratic legitimacy by boasting that Pezeshkian’s candidacy illustrated the legitimacy of Iran’s electoral process.[vi] Some Iranian university students confronted Pezeshkian in a meeting on June 16, framing his candidacy as an effort on the part of the regime to contribute to an “illusion of democracy” and an attempt by the regime to legitimize the elections.“[vii] The June 28 voter turnout rate was nevertheless unprecedently low at 40 percent, with the lowest recorded rates in Kermanshah, Kurdistan and Tehran provinces.[viii] It is noteworthy that a significant percentage of anti-regime protests during the Mahsa Amini movement occurred in Kurdistan and Tehran provinces, suggesting continued disillusionment with the Iranian regime in these regions.[ix]

Khamenei and segments of Iran’s clerical establishment have indirectly demonstrated a preference Jalili in recent days, making a Pezeshkian win unlikely regardless of how many votes he receives. Khamenei expressed foreign and nuclear policy views on June 25 that closely align with ultraconservative hardline presidential candidate Saeed Jalili’s views, suggesting that Khamenei endorses Jalili.[x] Khamenei also indirectly criticized Pezeshkian’s campaign policies on the same date, making it unlikely that Khamenei will permit him to become president. Segments of the Iranian clerical establishment may also back Jalili. Reformist-affiliated Entekhab News posted a screenshot on July 1 that it claimed showed coordination among Iranian clerics to campaign for Jalili in villages and cities across Iran.[xi] Entekhab also circulated reports on July 1 that the influential Qom Seminary in Iran will close this week for its students and teachers to help improve voter turnout. Entekhab suggested that the Qom Seminary closures corroborated reports of clerics campaigning for Jalili.[xii] It is likely, if the Qom Seminary closures are indeed connected with reports of clerics campaigning, that students and teachers will disperse to their hometowns—specifically rural areas—to generate support for Jalili. Rural and sparsely populated areas have historically served as a bastion of support for the regime and its hardline policies.[xiii] Roughly 35 percent of the Iranian population lives in rural areas and political engagement in these areas could furthermore improve voter turnout rates while benefiting Jalili.[xiv]

The Supreme Leader will risk further deteriorating regime legitimacy in the unlikely event that Pezeshkian garners enough votes to win the election. Khamenei has criticized Pezeshkian’s policies and echoed Jalili’s nuclear and foreign policies, indicating that Khamenei endorses Jalili over Pezeshkian. It is therefore unlikely that Khamenei will permit Pezeshkian to win, regardless of whether Pezeshkian receives the majority of votes. Raisi’s 2021 election suggests that Khamenei is comfortable engineering elections to advantage his preferred candidate.[xv] The Guardian Council denied the candidacies of several prominent politicians in the 2021 elections and Raisi therefore faced no significant competition in the race. It is unclear, however, how Khamenei will advantage his preferred candidate if Pezeshkian is able to generate increased support and win the election this week. The regime engineered the election results between reformist Mir Hossein Mousavi and hardline Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009, galvanizing a months-long anti-regime protest wave.[xvi] Khamenei will risk further deteriorating regime legitimacy and possibly kickstarting unrest in the unlikely event that Pezeshkian garners significant support in the coming days.

No candidate received the majority of votes needed to win the Iranian presidential election on June 28.[i] Iran will hold a runoff election between the two most popular candidates—ultraconservative Saeed Jalili and reformist Masoud Pezeshkian—on July 5.[ii] Jalili will likely win the runoff vote and become the next Iranian president. The Iranian regime reported that Pezeshkian received the most votes at around 10.4 million, while Jalili received around 9.5 million.[iii] Jalili will likely receive significantly more votes in the runoff election since there will be no other hardline candidates splitting the hardline vote. The second most prominent hardline candidate—Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf—received around 3.4 million votes, which was not enough to compete in the runoff election. At least some Ghalibaf voters will presumably back Jalili in the runoff election, giving him a significant advantage over Pezeshkian.

Jalili would run an ultraconservative hardline government similar to late-President Ebrahim Raisi. Such a president would likely exacerbate the economic and socio-cultural issues frustrating large swaths of the Iranian population. Jalili is a deeply ideological regime loyalist who has long supported extreme domestic and foreign policies. Western and Iranian opposition outlets reported that some Iranian hardliners, including senior officers from the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, tried to prevent Jalili from running for president, feeling that his views are too radical.[iv] Jalili downplayed the importance of external engagement to improve the Iranian economy during the presidential debates, suggesting that he might instead favor an autarkic agenda.[v] Jalili also voiced support for Iran’s “nuclear rights” and criticized the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in the debates.[vi] These comments are particularly concerning given that Iran has in recent months expanded its nuclear program significantly and begun running computer simulations that could help build a nuclear weapon.

The presidential election on June 28 saw unprecedently low voter turnout, highlighting widespread disillusionment with the Iranian regime. The Iranian Interior Ministry announced that around 25.5 million votes were cast, which is around 40 percent of the Iranian electorate.[vii] Notwithstanding the possibility that the regime inflated these numbers, they reflect a notable drop-off from the roughly 48.5-percent turnout for the Iranian presidential election in 2021.[viii]

Iran held its presidential election on June 28.[i] Iran will likely have to hold a runoff election on July 5 given that neither of the two hardline frontrunners—Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and Saeed Jalili—withdrew from the election before the first round of voting on June 28. Four candidates—pragmatic hardliner Ghalibaf, ultraconservative hardliner Jalili, reformist Masoud Pezeshkian, and hardliner Mostafa Pour Mohammadi—participated in the June 28 election. The Iranian constitution stipulates that a candidate must win over 50 percent of the vote to become president.[ii] Senior hardline Iranian officials have repeatedly called in recent weeks on the hardline candidates to coalesce around a single candidate.[iii] These calls were driven by concerns that splitting the hardline vote across numerous candidates could inadvertently advantage the sole reformist candidate, Pezeshkian. Two unspecified Iranian officials confirmed to the New York Times on June 28 that Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Quds Force Commander Brigadier General Esmail Ghaani called on Jalili to withdraw from the race during an emergency meeting with Jalili and Ghalibaf in Mashhad, Iran, on June 26.[iv] Ghaani reportedly stated that Ghalibaf is better qualified than Jalili to run the government because of his “military background and pragmatic outlook.”[v] Ghaani’s characterization of Ghalibaf as “pragmatic” is consistent with recent Western reports that some IRGC factions are trying to prevent Jalili from winning the election because they regard him as “too hardline.”[vi] Ghaani’s intervention also highlights hardliners’ concerns that Pezeshkian could pose a real threat to Jalili and Ghalibaf in the election. The New York Times later deleted its report about Ghaani’s meeting with Jalili and Ghalibaf without providing an explanation.

Preliminary reports suggest that most Iranians did not participate in the June 28 election. The Iranian Election Headquarters extended the voting deadline twice until 2200 local time, likely to try to increase voter turnout.[vii] This action is not unprecedented; the regime has previously extended voting hours during both presidential and parliamentary elections.[viii] The decision to extend the voting deadline nevertheless highlights that voter turnout likely did not reach the regime’s desired level during the regular voting hours. The Interior Ministry, which runs elections in Iran, reportedly estimated a voter turnout of less than 30 percent by 2000 local time.[ix] A Tehran-based researcher similarly claimed that turnout only reached approximately 35 percent by 2115 local time.[x] CTP-ISW cannot independently verify these reports. Opposition media separately circulated videos of poll workers sleeping at empty voting centers and reported that the regime forced prisoners in Kurdistan Province to vote to boost voter turnout statistics.[xi]

Iranian hardliners have made only limited progress toward uniting behind a single candidate ahead of the Iranian presidential election on June 28. Remaining divisions among the hardliners by the time of the vote significantly increases the likelihood of a runoff election. Two hardline candidates—Amir Hossein Ghazi Zadeh Hashemi and Ali Reza Zakani—have withdrawn from the race since June 26 in order to help unify their faction.[i] Neither candidate was especially popular, however, making it unclear that their exits will meaningfully affect the vote. The two most prominent hardline candidates (Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and Saeed Jalili) remain in the race and have refused to withdraw in support of the other at the time of this writing. Ghalibaf and Jalili both staying in the election ensures that they will split at least some of the hardliner vote. It will also likely prevent either from reaching the majority needed to win—unless the supreme leader and his inner circle manipulate the vote blatantly to favor either candidate. Iran will hold a runoff election between the two most popular candidates on July 5 if no one wins the majority.[ii]

Some hardliners, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, appear concerned that the sole reformist candidate, Masoud Pezeshkian, could win the vote outright. Khamenei indirectly criticized Pezeshkian on June 25 for supporting engagement with the West, indicating Khamenei’s opposition to him.[iii] The Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), which is run by hardliners, additionally cancelled one of Pezeshkian‘s rallies at the last minute on June 26, further indicating that some in the regime view him as a serious contender for the presidency.[iv] The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) has separately tried to unite the hardline camp against Pezeshkian, according to unverified social media rumors. IRGC Quds Force Commander Brigadier General Esmail Ghaani reportedly met with Ghalibaf and Jalili in Mashhad on June 26 to form a consensus between them.[v] Ghaani clearly failed, if this reporting is accurate. But his intervention is nonetheless remarkable and possibly unprecedented, reflecting hardliners’ serious concerns about Pezeshkian.

Hardline candidate Amir Hossein Ghazi Zadeh Hashemi withdrew from the Iranian presidential election on June 26.[i] Hashemi did not appear to have a serious chance at winning and withdrew to avoid splitting votes across too many hardline candidates.[ii] It is unclear, however, whether his withdrawal will meaningfully benefit the two hardline frontrunners, Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and Saeed Jalili. An unspecified hardline Iranian source told the Middle East Eye on June 25 that Hashemi supports Jalili and hopes to receive a political appointment if Jalili becomes president.[iii] Hashemi’s withdrawal follows repeated calls from senior hardline officials in recent weeks for the hardline faction to coalesce behind a single candidate.[iv] These calls are driven by concerns that splitting the hardline vote across numerous candidates could inadvertently advantage the sole reformist candidate, Masoud Pezeshkian.

Iranian presidential candidates reiterated their economic policies during the final debate of the upcoming election.[v] This debate occurred on June 25 and focused on the economy. Below are the key takeaways from what the three presumed frontrunners said.

- Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf (pragmatic hardliner): Ghalibaf again framed his candidacy as a continuation of the Ebrahim Raisi administration.[vi] Ghalibaf claimed that he would increase workers’ salaries to match rising inflation and criticized other candidates’ lack of managerial experience.

- Saeed Jalili (ultraconservative hardliner): Jalili identified employment rates and inflation as the greatest issues facing the Iranian economy.[vii] Jalili notably did not mention the role of international sanctions in this context. Jalili also called for deepening economic ties with China and increasing non-oil exports.

- Masoud Pezeshkian (reformist): Pezeshkian vowed to implement the seventh five-year development plan, which is a Raisi-era agenda aimed at increasing economic growth, minimizing government debt, and optimizing the state budget.[viii] Pezeshkian also said that he would focus on external economic engagement and secure sanctions relief.

Upon reviewing Iranian polling data, CTP-ISW has concluded that recently published polls cannot accurately or meaningfully predict who will win the upcoming Iranian presidential election. Most of the polls include large percentages of voters who have not yet decided for which candidate they will vote. A June 24 Iranian Students Polling Agency poll, for example, showed that 30.6 percent of respondents had not decided for which candidate they would vote.[ix] A June 26 Parliamentary Research Center poll similarly showed that 28.5 percent of respondents had not decided which candidate they will support.[x] The large percentage of undecided voters makes it extremely difficult for these polls to accurately predict the election outcome given that candidates need to win the majority vote to win the race.

Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei expressed foreign and nuclear policy views on June 25 that closely align with ultraconservative hardline presidential candidate Saeed Jalili’s views, possibly indicating that Khamenei endorses Jalili in the upcoming election. Khamenei’s views also signal the supreme leader’s opposition to reformist candidate Masoud Pezeshkian. Khamenei expressed strong opposition to mending ties with the United States during a speech on June 25, which mirrored similar statements made by Jalili in a foreign policy debate on June 24.[i] Jalili defended Iran’s “nuclear rights” and criticized the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) during the debate.[ii] Khamenei also indirectly criticized Pezeshkian, stating that politicians who are “attached to America” cannot be “good managers.”[iii] Pezeshkian expressed support for improving relations and resuming nuclear negotiations with the West during the June 24 foreign policy debate.[iv] Pezeshkian stated that “no country in history has been able to achieve prosperity and growth by closing its borders and wanting to work alone.”[v] Khamenei’s criticisms of Pezeshkian may also stem from the fact that Pezeshkian has closely coordinated his presidential campaign with Mohammad Javad Zarif, who served as Iran’s foreign affairs minister under former moderate President Hassan Rouhani. Pragmatic hardliner Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf also expressed support for nuclear negotiations during the June 24 debate, which is consistent with recent reports from Iranian opposition outlets that advisers to Ghalibaf have approached Western diplomats in recent weeks.[vi]

Khamenei’s possible endorsement of Jalili would diverge from some Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) factions’ support for pragmatic hardline candidate Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf. The Telegraph reported in early June 2024 that some senior IRGC commanders, including former IRGC Air Force Commander Hossein Dehghan, are supporting Ghalibaf.[vii] An IRGC member told the Telegraph that some IRGC factions are trying to prevent Jalili from winning the election because they regard him as “too hardline.”[viii] IRGC Aerospace Force Commander Brigadier General Amir Ali Haji Zadeh separately stated on June 24 that Iran’s next president must have “strong executive management” experience.[ix] Some Western commentators and analysts have interpreted Haji Zadeh’s statement as an implicit endorsement of Ghalibaf given Ghalibaf’s experience serving as Iran's parliament speaker since 2020.[x] Ghalibaf has decades-old ties to many senior IRGC officers dating back to their time fighting in the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s.[xi] Ghalibaf is also part of a close circle of current and former IRGC officers who have repeatedly come together in times of domestic crisis to interfere in Iranian domestic politics.[xii]

Khamenei’s explicit opposition to engagement with the West also challenges recent Western reports that incorrectly suggested that Iran is seeking to renew nuclear talks with the West. Iranian Permanent Representative to the UN Saeed Iravani stated that the JCPOA is “not perfect” but is the “best option” during a UN Security Council meeting on June 24.[xiii] Some Western media outlets incorrectly interpreted Iravani’s statement as signaling the Iranian regime’s readiness to renew nuclear negotiations. Iravani’s statements were instead consistent with repeated statements by regime officials blaming the current state of the JCPOA on the United States and E3 (the United Kingdom, France, Germany). Iravani accused the United States of “unilaterally and illegally” withdrawing from the JCPOA and accused the E3 of “failing” to fulfill their JCPOA obligations.[xiv] Jalili additionally accused the United States and the E3 of lacking “sincerity and determination” to revive the JCPOA.

Iranian presidential candidates discussed socio-cultural issues during the third debate for the upcoming election. None of the presumed frontrunners (Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, Saeed Jalili, and Masoud Pezeshkian) suggested that they would support fundamental changes to long-standing regime policies. All three frontrunners indicated support for the mandatory hijab law and did not suggest that they would support easing restrictions on women’s dress code.[x] That none of these candidates challenged the regime policy reflects their subordination to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who has expressed opposition repeatedly to changing the hijab requirement. Khamenei has described veiling as an “irrevocable, religious necessity.”[xi] The frontrunners did debate slightly how to enforce the mandatory hijab law.

- Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf (pragmatic hardliner). Ghalibaf emphasized that all regime bodies—not just the national police force—should encourage and enforce the hijab requirement.[xii] Ghalibaf claimed that some regime bodies have supported the police insufficiently in enforcing the mandatory hijab law, leading to violent confrontations between the regime and unveiled women. Ghalibaf also expressed support for a recent hijab enforcement bill that Parliament is considering currently. The legislation codifies legal punishments, including fines and salary cuts, for women who violate the hijab requirement.[xiii]

- Masoud Pezeshkian (reformist). Pezeshkian emphasized his opposition to using violence to enforce the mandatory hijab law but did not propose changing the law itself.[xiv] Pezeshkian described regime treatment of unveiled women as immoral. Pezeshkian also argued that the regime could stop women from questioning the need to veil by changing how it educates girls in mosques and schools. This statement mirrors similar remarks from Khamenei calling for greater emphasis on indoctrinating Iranian youth in order to resolve social issues.[xv]

- Saeed Jalili (ultraconservative hardliner). Jalili avoided addressing the hijab issue directly and instead focused on criticizing the West. Jalili accused the West of hypocrisy for condemning Iran for treating women harshly while ignoring the deaths of Palestinian women in the Gaza Strip.[xvi]

The frontrunners’ comments on the mandatory hijab law reflect their efforts to appeal to certain demographics. Pezeshkian has consistently tried to rally Iranian youth who are frustrated with the harsh enforcement of the hijab requirement. Jalili contrastingly tried to pander to hardline, anti-Western voters in order to distinguish himself from Ghalibaf.

The frontrunning candidates separately expressed support for ongoing censorship and internet restrictions in Iran. Ghalibaf and Pezeshkian both claimed that they support internet freedom but added that censorship is necessary during “crises.”[xvii] Ghalibaf emphasized the need to “carefully and intelligently monitor” the internet and expressed support for building the national intranet, which would increase regime control of the Iranian domestic information space.[xviii] Jalili praised regime efforts to develop indigenous communications and social media platforms as alternatives to Western platforms.[xix]

Iranian presidential candidates discussed government management and service provision during the second debate for the upcoming election.[i] The debate occurred on June 20. The candidates spoke in generalities without describing substantive policies to address domestic issues for much of the debate. Below are the key takeaways from what the three presumed frontrunners said in the debate.

- Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf (pragmatic hardliner): Ghalibaf presented the most discrete policy positions among the frontrunners. Ghalibaf reiterated readiness to negotiate with the West in order to secure relief from international sanctions.[ii] He discussed increasing wages to match inflation and launching a ”multi-layered” social security insurance program.[iii] Ghalibaf also reiterated support for foreign currency investment in Iran. Ghalibaf separately advocated for building a border wall dividing Iran from Afghanistan and Pakistan.[iv]

- Saeed Jalili (ultraconservative hardliner): Jalili discussed resolving domestic issues but downplayed the importance of external economic interaction. Jalili discussed increasing food subsidies, managing energy consumption, and preventing brain drain.[v] Jalili also hesitated to endorse negotiations with the West and dismissed the need for Iran to adhere to international anti-corruption and transparency standards. Jalili separately criticized the Iranian healthcare system.

- Masoud Pezeshkian (reformist): Pezeshkian emphasizes his subordination to the supreme leader, as he has done repeatedly throughout his campaign.[vi] His rhetoric reaffirms that, if elected, he would be constrained by whatever political boundaries the supreme leader sets just as every Iranian president is. Pezeshkian expressed support for loans and public works projects for rural communities. He also emphasized the importance of countering corruption and promoting education.[vii]

Iranian reformist presidential candidate Masoud Pezeshkian is continuing to struggle to consolidate support among Iranian youth ahead of the June 28 election. Pezeshkian promoted reformist ideals such as increased international engagement and freedom of thought during a meeting with Esfahan University students on June 19.[xi] This meeting marked Pezeshkian’s second meeting with university students—a key voter demographic—since June 16.[xii] Pezeshkian called on Iranian students to vote in the upcoming election, warning that boycotting the election could lead to greater restrictions and repression.[xiii] A Esfahan University student accused Pezeshkian of participating in the election to increase voter turnout and claimed that 90 percent of Iranian youth intend to boycott the election.[xiv] The student added that many Iranian youth do not care who becomes president because they oppose the regime as a whole.[xv] Another Esfahan University student questioned Pezeshkian’s ability to challenge mandatory hijab enforcement.[xvi] These statements follow a similar statement by Sharif University students on June 16 that questioned impact of the Iranian president on regime decision-making and called on Pezeshkian to withdraw from the election if he cannot guarantee meaningful change.[xvii]

Iranian presidential candidates discussed the economy in the first debate for the upcoming election.[i] The debate occurred on June 17. Below are the key takeaways from what the three presumed frontrunners said in the debate.

- Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf (hardliner): Ghalibaf expressed openness to nuclear negotiations with the West in order to remove sanctions from the economy.[ii] Ghalibaf suggested that a phased agreement could work to secure sanctions relief. Ghalibaf’s comments are consistent with reports from Iranian opposition outlets saying that advisers to Ghalibaf have approached Western diplomats in recent weeks. CTP-ISW noted at the time that the outreach is possibly meant to set conditions for the resumption of nuclear negotiations if Ghalibaf becomes president.[iii] Ghalibaf also lamented that economic agreements that Iran has signed with China and Russia have not yet been operationalized.[iv] Ghalibaf separately identified inflation as one of the most pressing economic issues.

- Saeed Jalili (hardliner). Jalili contrastingly downplayed the importance of nuclear negotiations with the West.[v] Jalili criticized past Iranian presidents, specifically Hassan Rouhani, for relying on international agreements to solve economic issues. Jalili instead promoted an agenda focused on autarkic policies and self-sufficiency. Jalili attributed issues, such as inflation and the struggling private sector, to resource mismanagement.

Masoud Pezeshkian (reformist). Pezeshkian advocated for expanding economic diplomacy with regional and extra-regional countries.[vi] Pezeshkian asserted that Iran needs economic interaction with other countries in order to grow its economy. He specifically called for Iran to increase its exports and foreign investment. Pezeshkian separately stated that international sanctions have been a “disaster” for Iran, which is consistent with his historic support for the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.[vii]

The dates and topics of the upcoming Iranian presidential debates are as follows:[viii]

June 20 |

“justice-oriented services to the government,” |

June 21 |

Culture and “social cohesion,” |

June 24 |

Iran’s role in the world, |

June 25 |

The economy |

Iranian reformist presidential candidate Masoud Pezeshkian appears to be struggling to consolidate support among Iranian youth, a key voter demographic.[xx] Pezeshkian promoted reformist ideals such as increased international engagement and looser social restrictions during a discussion with Tehran University students on June 16.[xxi] Pezeshkian also stressed his subordination to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, discouraging students from criticizing Khamenei or his role within the regime. A group of Sharif University students read a statement that questioned the utility of the Iranian presidency and called Pezeshkian’s campaign a ”colorful deception” after Pezeshkian’s talk.[xxii] The students stressed that Iranian presidents do ”not have the ability to influence the decisions of" the supreme leader and that ”there is no guarantee that [Iranian presidents have] authority in internal decisions.” The students called on Pezeshkian to withdraw from the election unless he could guarantee meaningful change within the regime, saying that failing to withdraw would contribute to ”the illusion of democracy.” Pezeshkian is currently attempting to balance his subordination to Khamenei with his reformist agenda, as CTP-ISW has previously noted.[xxiii]

The Sharif University students’ statements—while not emblematic of all individuals in this demographic—are demonstrative of the increased disillusionment of Iranian youth in recent years. The Sharif University students’ criticisms of Pezeshkian’s campaign is indicative of a widening gap between the Iranian reformist party—who are dedicated to preserving the Islamic Republic and serving its Supreme Leader—and a key voter demographic. Iranians between ages 10 and 24 encompassed roughly 20 percent of the country’s population in 2021 and Iranian youth has historically favored candidates pursuing moderate or reformist agendas.[xxiv] Iranian youth and specifically university students have led anti-regime protest movements in recent years. These protest movements have openly criticized the regime’s core principles, including Velayat-e Faqih, and in some cases called for the regime’s collapse.[xxv] The response of this group of university students highlights the widening gap between Iranian youth and students and Pezeshkian and other Iranian reformists.

A hardline Iranian cleric and parliamentarian claimed on June 17 that unspecified hardline presidential candidates have agreed to withdraw from the election if they perform poorly in upcoming presidential debates.[xxvi] Iran will hold five televised debates beginning on June 17.[xxvii] Reza Taghavi claimed that four unspecified ”trusted institutions” will rate the hardline candidates based on their performance in the debates and that “some candidates” have agreed to withdraw in support of the candidate with the best performance.[xxviii]

Taghavi’s claim follows repeated statements from hardline officials calling on the hardline camp to reach a “consensus” ahead of the June 28 election.[xxix] These calls are driven by concerns that the five hardline candidates risk splitting the vote and inadvertently advantaging the sole reformist candidate, Masoud Pezeshkian.

Iranian hardliners are debating and negotiating amongst themselves to unite their faction behind a single candidate in the Iranian presidential election. The faction is concerned that the five hardline candidates risk splitting the vote and inadvertently advantaging the sole reformist candidate, Masoud Pezeshkian. Some hardliners are urging Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf or Saeed Jalili to withdraw in support of the other.[xxiii] Other hardline officials and media outlets are expressing concerns that that the faction is too divided to win the race.[xxiv] Ali Reza Zakani, who is a hardline candidate and the Tehran City mayor, stated on June 13 that candidates who are behind in electoral polls should withdraw in favor of more popular contenders.[xxv]

Iranian Parliament Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf is framing his candidacy in the presidential election around improving the Iranian economy. Ghalibaf has discussed in recent days the need to improve economic conditions in Iran and chose “service and progress” as his campaign slogan.[i] Ghalibaf also emphasized the need to increase production in the automotive, energy and housing industries and advocated against price fixing.[ii] Ghalibaf affirmed that he will implement the seventh five-year development plan, which is a Raisi-era document focused partly on curbing inflation, optimizing the state budget, and resolving government debts.[iii] Ghalibaf’s emphatic support for the five-year development plan indicates that he is trying to frame his candidacy as least partly as a continuation of the policies of late-President Ebrahim Raisi.

Ghalibaf appointed Ali Nikzad—a hardline, ethnically Azeri parliamentarian—as his campaign manager on June 10.[iv] Nikzad previously worked in Raisi’s presidential campaigns in 2017 and 2021.[v] An Iranian opposition outlet suggested that Ghalibaf hired Nikzad to garner support from the Iranian Azeri population and rural, conservative communities. The outlet also suggested that hiring Nikzad could be meant to balance against reformist candidate Masoud Pezeshkian, who is an ethnic Azeri as well. Nikzad and Pezeshkian have both represented heavily Azeri constituencies in Parliament.

Iranian reformist presidential candidate Masoud Pezeshkian is trying to balance his relatively moderate agenda with his need to maintain the approval of the Iranian supreme leader. Pezeshkian emphasized the Iranian president’s subordination to the supreme leader in his first televised interview on June 10, stating that “the general policies of the supreme leader are clear, and any administration that governs must implement [these general policies].”[xxii] Pezeshkian made these comments in the context of implementing Iran’s next five-year development plan. Iran’s five-year development plan is a document that outlines Iran’s budget and development policies throughout a five-year period. Pezeshkian separately promoted reformist ideas in an interview with a reformist newspaper on June 11, illustrating the precariousness with which Pezeshkian must balance his subordination to the supreme leader and his reformist agenda.[xxiii] Pezeshkian defended Iranians’ right to protest, noting that “all protests stem from injustice. . . you can’t take the rights of an individual away and tell them to be quiet” and advocated for a less aggressive veiling enforcement policy. Pezeshkian’s June 10 comments stressing the supreme leader’s role in setting Iran’s policies are not uncharacteristic of a reformist candidate.

Most—if not all—actors in the Iranian political spectrum are ultimately dedicated to preserving the Islamic Republic and serving its supreme leader. Pezeshkian likely seeks to generate support by discussing popular reforms supported by Iranian youth, including economic engagement with the West and mandatory veiling. Pezeshkian—and any other reformist—must work within the system to implement reforms, all of which would need to be approved by the supreme leader. This means that the reformist camp works from an inherent disadvantage because reforms promised by a presidential candidate will not be implemented unless the reforms have the supreme leader’s approval, and he is less likely to grant to reformist policies. Hardliners do not have the same restrictions because their policies are more likely to be green lit by the supreme leader.

Voter participation in Iranian presidential elections have significantly decreased in recent years due to decreased political representation and election engineering.[xxiv] It is unclear if Pezeshkian, the sole reformist candidate, will instill greater confidence in the integrity of the regime’s electoral system and improve voter turnout. The Guardian Council—the regime entity responsible for vetting and approving presidential candidates—boasted on June 11 that the “unpredictable” list of approved candidates demonstrated the equity with which candidates were reviewed.[xxv] The council heavily engineered the 2021 presidential elections to favor former President Ebrahim Raisi.[xxvi] It is unlikely that Pezeshkian's participation in the 2024 elections will repair the damage done by the 2021 election engineering or improve voters' trust and subsequent participation in the process.

The Iranian Guardian Council approved a pool of six candidates that included mostly hardliners for the upcoming 2024 presidential election. The six approved candidates include five hardliners and one reformist on June 9 for the upcoming presidential election.[i] The Iranian regime likely approved the sole reformist candidate to feign political diversity and therefore increase voter participation. Iranian officials have emphasized the need for ”competitive” and ”participatory” elections.[ii] Iran recorded record low voter turnout in its March 2024 parliamentary election, though the real voter turnout was likely even lower than the officially recorded turnout.[iii] The Guardian Council approved the following individuals to run for president:

- Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf (Hardliner). Ghalibaf is a hardline politician who has served as Iran’s parliament speaker since 2020.[iv] Parliamentarians recently re-elected Ghalibaf as parliament speaker on May 28.[v] Ghalibaf is a long-time member of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), having served as the IRGC Air Force commander between 1997 and 2000.[vi]He is a very well-connected politician who maintains close personal relationships with the highest echelons of the IRGC dating back to the Iran-Iraq War.[vii] Ghalibaf also served as Iran’s police chief between 2000 and 2005.[viii] This marks Ghalibaf’s fourth bid for the presidency.[ix]

- Saeed Jalili (Hardliner). Jalili is a hardline politician and diplomat who currently serves as a member of the Expediency Discernment Council.[x] Jalili previously served as the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and chief nuclear negotiator from 2007 to 2013.[xi] Jalili currently serves as the Supreme Leader’s representative to the SNSC.[xii] This marks Jalili’s third bid for the presidency.[xiii]

- Amir Hossein Ghazi Zadeh Hashemi (Hardliner). Hashemi is a hardline politician who has served as vice president and the head of the Martyrs and Veterans Affairs Foundation in the Raisi administration from 2021 to the present.[xiv] Hashemi served as a representative for Mashhad in parliament from 2008 to 2021.[xv] Hashemi ran for president and lost in 2021.[xvi]

- Ali Reza Zakani (Hardliner). Zakani is a hardline politician who has served as the mayor of Tehran since 2021.[xvii] The Guardian Council barred Zakani from running in the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections.[xviii] Zakani competed in the 2021 presidential election but ultimately withdrew his candidacy in support of Raisi.[xix] Zakani previously headed the Student Basij Organization during the crackdown on student protesters in July 1999.[xx]

- Mostafa Pour Mohammadi (Hardliner). Pour Mohammadi is a hardline politician and cleric from Qom.[xxi] Pour Mohammadi served as the Justice Minister under President Hassan Rouhani from 2013 to 2017.[xxii] Pour Mohammadi notoriously served with former President Ebrahim Raisi on the 1988 ”Death Commission,” which approved the executions of thousands of political prisoners.[xxiii]

- Masoud Pezeshkian (Reformist): Pezeshkian is the sole reformist politician the Guardian Council permitted to run in the 2024 presidential election. Pezeshkian is an ethnic Azeri who has represented Tabriz, near the Iran-Azerbaijan border, from 2008 to present.[xxiv] Pezeshkian was initially disqualified from running in the 2024 parliamentary elections, but the Guardian Council later permitted him to run. Pezeshkian has criticized the Iranian government over the issue of hijab enforcement.[xxv] Pezeshkian announced that Mohammad Javad Zarif would serve as his foreign minister should he be elected president.[xxvi]

The candidacy of five Iranian hardliners risks an electoral challenge for the hardline camp, wherein the hardline votes could be split amongst the five candidates. The hardline camp may split its votes amongst the five hardline candidates, which would benefit the sole reformist candidate.[xxvii] It is likely that some hardline candidates will withdraw from the election to prevent the vote from splitting. The moderate-reformist camp, by comparison, appears relatively united. Reform Front Spokesperson Javad Emam stated on June 8 that reformist politicians would not participate in the upcoming presidential election unless one of their candidates—including Masoud Pezeshkian—was approved.[xxviii] Multiple elements of the reformist camp expressed support for reformist candidate Masoud Pezeshkian on June 10.[xxix]

The Guardian Council did not approve the candidacy of some high-profile politicians, including former Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani and adviser to the supreme leader Vahid Haghanian.[xxx] The disqualification of Larijani illustrates the increased isolation of the once-prominent Larijani family from the regime.[xxxi] The Guardian Council also disqualified a close aide to supreme leader, Vahid Haghanian.[xxxii] The disqualification of Haghanian illustrates that the regime is going as far as to reject elements of its own government that it has trusted for decades. These disqualifications emphasize the regime’s commitment to engineering who will be the next president by limiting the pool of approved candidates.

Iranian Parliament Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf’s advisers have spoken to Western diplomats in recent weeks, possibly to set conditions for the resumption of nuclear negotiations if he becomes president. An Iranian opposition outlet reported on June 10 that Ghalibaf’s advisers have talked to US and European diplomats over the past two weeks, citing an unspecified European diplomat.[xxxiii] The advisers have emphasized Ghalibaf’s willingness to “improve Iran’s relations with the rest of the world” and to “cleanse” the Iranian regime of “radical elements” during the advisers’ conversations with foreign officials.[xxxiv] The advisers have also emphasized that Ghalibaf would play a significant role in stabilizing the Iranian regime following Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s death.[xxxv] Ghalibaf is one of six candidates the Guardian Council approved to compete in the June 28 presidential election.[xxxvi] Ghalibaf is a pragmatic hardliner who has previously called for limited political and economic reforms within the framework of the Islamic Republic.[xxxvii] Ghalibaf may be trying to signal to Western governments that his administration would be more willing than the hardline Ebrahim Raisi administration to conduct nuclear negotiations and conclude a new nuclear deal.

Iranian hardline officials are continuing to try to promote an electoral consensus among hardliners ahead of the June 28 presidential election. These efforts probably seek to avoid infighting between Iranian hardliners that could provide an opening for a more moderate candidate to win the presidency. Former IRGC Commander Mohsen Rezaei called for “synergy and unity” among hardliners in a Twitter (X) post on June 5.[i] Rezaei similarly called for a "consensus” among "revolutionary forces” during a meeting with Martyrs and Veterans Affairs Foundation President Amir Hossein Ghazi Zadeh Hashemi and Parliamentary Economic Committee Chairman Mohammad Reza Pour Ebrahimi on June 4.[ii] Hardline politician Gholam Ali Haddad Adel separately called on hardliners on June 6 to support a single candidate in the upcoming election.[iii] Haddad Adel warned that hardliners could suffer a “defeat” in the election if they support a “plurality of candidates.”[iv] Haddad Adel added that supporting a “plurality of candidates” could lead to a repeat of the 2013 presidential election in which a reformist candidate, Hassan Rouhani, won the presidency.[v]

Former IRGC Commander Mohsen Rezaei appears to be trying to promote an electoral consensus among hardliners ahead of the June 28 Iranian presidential election. Rezaei met with Martyrs and Veterans Affairs Foundation President Amir Hossein Ghazi Zadeh Hashemi and Parliamentary Economic Committee Chairman Mohammad Reza Pour Ebrahimi on June 4 to promote a "consensus” among "revolutionary forces” ahead of the upcoming election.[xiii] The June 4 meeting comes shortly after Rezaei and Interim President Mohammad Mokhber met with Parliament Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and expressed support for his candidacy.[xiv] Hashemi is reportedly part of a political faction that supports Roads and Urban Development Minister Mehrdad Bazrpash for president.[xv] It is possible that Rezaei is attempting to rally the hardline camp behind Ghalibaf.

Senior officials tied to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) are supporting Iranian Parliament Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf in the Iranian presidential election. Iranian media reported on June 4 that former IRGC Commander Mohsen Rezaei and Interim President Mohammad Mokhber recently met with Ghalibaf and expressed support for his candidacy.[xviii] Their backing alleviated Ghalibaf’s “doubts” about running, according to the Iranian reports.[xix] The Telegraph similarly reported that IRGC factions, including former IRGC Air Force Commander Hossein Dehghan, are supporting Ghalibaf.[xx] Dehghan is currently a senior adviser for defense industrial policy to the Iranian supreme leader. The Telegraph reported that individuals close to Dehghan ”are contacting everyone they know” to improve Ghalibaf’s chances. Ghalibaf—like Rezaei and Dehghan—is himself a former IRGC commander. Ghalibaf headed the IRGC Air Force from 1997 to 2000. He also has deep personal ties dating back to the Iran-Iraq War to many senior officers in the Iranian security establishment.[xxi]

Ghalibaf and other prominent figures are apparently focused on preventing Saeed Jalili in particular from winning the election. The Telegraph reported that some IRGC factions are trying to prevent Jalili from winning because they consider him too extreme politically.[xxii] Jalili serves as one of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s personal representatives to the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and was the SNSC secretary from 2007 to 2013. A former official from the Iranian Interior Ministry told the Telegraph that individuals close to Ghalibaf oppose Jalili and “are contacting everyone they know to block Jalili.” An Iranian opposition outlet similarly reported in May 2024 that elements in the regime tried to convince Khamenei to prevent Jalili from competing in the election.[xxiii] These elements included Ghalibaf as well as other hardliners, such as Expediency Discernment Council Chairman Sadegh Amoli Larijani and senior adviser to the supreme leader Ali Shamkhani. These elements also included some moderates, such as Ali Larijani, who is the brother of Sadegh.

Ghalibaf and Jalili were previously at odds during the Mahsa Amini protest movement in Iran in late 2022. Ghalibaf accused Jalili of adopting too harsh a stance vis-a-vis the protests and exacerbating frustrations among disaffected Iranian youth.[xxiv] Ghalibaf contrastingly called for limited economic and political reforms to address protester grievances. Ghalibaf could use this contrast to appeal to more moderate elements in the Iranian political establishment.

Two factions from the Ebrahim Raisi administration are vying for the Iranian presidency, according to Iranian media.[xxv] These factions revolve around Culture and Islamic Guidance Minister Mohammad Esmaili and Roads and Urban Development Minister Mehrdad Bazrpash, both of whom registered as candidates for the election. Esmaili’s faction includes Planning and Budget Organization Director Davoud Manzour and Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare Minister Solat Mortazavi. Bazrpash’s faction includes Martyrs and Veterans Affairs Foundation President Amir Hossein Ghazi Zadeh Hashemi.