{{currentView.title}}

December 04, 2024

Africa File Special Edition: Syria’s Potential Impact on Russia’s Africa and Mediterranean Ambitions

Data Cutoff: December 4, 2024, at 10 a.m.

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here. Follow CTP on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook.

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways: Russia may redeploy Africa Corps units to Syria to reinforce the Assad regime in Syria to prevent Assad’s defeat, which would harm the Kremlin’s strategic objectives in Africa and surrounding waterways such as the Mediterranean and Red Seas. Africa Corps may shore up Syrian regime forces in support and advisory roles but likely lacks capacity to send adequate numbers of troops to change the situation fundamentally. It is too soon to say how far the Syrian rebels can advance and whether they will be able to hold their gains. However, a scenario in which the rebels toppled Bashar al Assad would harm the Kremlin’s strategic objectives to project power in the Mediterranean and Red Seas and threaten NATO’s southern flank from Africa and the Mediterranean. Russia will face logistic challenges that will undermine its Africa operations if it loses its footprint in Syria. Assad’s collapse would additionally damage the global perception of Russia as an effective partner and protector, potentially threatening Russia’s partnerships with African autocrats and its resulting economic, military, and political influence in Africa.

Assessments:

Russia may redeploy Africa Corps units to Syria to reinforce the Assad regime in Syria. Ukraine’s Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) claimed on December 3 that the Kremlin had decided to redeploy “private military contractors, probably Africa Corps” units to Syria in response to the surprise Syrian rebel offensive in late November.[1] The claim did not elaborate on the number of forces or where they would come from. Russia has two military facilities in Syria’s Latakia province that could receive reinforcements: Hmeimim Air Base near Latakia and the Russian Navy base at Tartus. Syrian rebels captured Syria’s second-largest city, Aleppo, on December 1 and advanced south toward Hama City by December 3.[2] Hama is less than 30 miles north of Homs, Syria’s third-largest city; a gateway to the Mediterranean coast; and 90 miles north of the Syrian capital, Damascus.

Figure 1. Syrian Civil War

Source: Institute for the Study of War; Critical Threats Project.

Russia previously redeployed Africa Corps units away from African theaters during Ukraine’s incursion into Russia’s Kursk Oblast in August 2024, establishing a precedent for using Africa Corps personnel to plug manpower gaps in higher-priority theaters.[3] It is unclear how many Africa Corps personnel deployed to Kursk, which countries the Kremlin pulled them from, and whether they have returned to Africa since. The Africa Corps-affiliated “Bear Brigade,” a 100-strong detachment, had redeployed from Burkina Faso to Kursk Oblast as of late August.[4] Some Kremlin-affiliated milbloggers referred to other reinforcements as Africa Corps “reserves” who were still based in Russia and had not yet deployed to Africa.[5]

Figure 2. Africa Corps Deployments in Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

Africa Corps units are the best-positioned Russian assets to redeploy to Syria and reinforce Russian efforts there. Russia has stopped sending supplies through the Black Sea to reach Syria due to the proliferation of Ukrainian air and naval drones, forcing them to take a much longer voyage around Europe via the Baltic.[6] Libya serves as a hub for Africa Corps personnel and heavy equipment, which can reach Syria via the Mediterranean Sea.[7] Russia reinforced the estimated 800 soldiers who were in Libya at the beginning of 2024 with over 1,800 regular Africa Corps units and several hundred special forces by March.[8] The Kremlin sent several shipments from Syria to Libya during this period, amounting to tens of thousands of tons of military equipment.[9] Russia has presumably deployed some of these soldiers and equipment to sub-Saharan Africa or Ukraine throughout 2024, but the remaining assets are best positioned to reach Syria quickly and without drawing resources away from Ukraine or, potentially, the Sahel. The equipment shipments included T-72 tanks and artillery systems that CTP has not recorded appearing in other sub-Saharan theaters and are presumably still in Libya, and the Polish Institute of International Affairs reported that Russia had roughly 1,800 troops across Libya as of May 2024.[10]

Africa Corps may help shore up Syrian regime forces in support and advisory roles but likely lacks the capacity to send adequate numbers of troops to change the situation in Syria fundamentally. Africa Corps units in Mali and Russian veterans who served in Libya in 2019 have experience with the kinds of administrative command support and tactical-level advising that Russian forces have previously provided to help augment regime forces in Syria.[11] Several Africa Corps commanders in Libya even served in Syria before deploying to Libya in 2024.[12]

The Kremlin will likely face capacity and logistic challenges in redeploying sufficient Africa Corps troops to Syria and sustaining its operations in Africa. Russia previously deployed thousands of ground forces to help shore up the Syrian regime after 2015, but CTP has recently assessed that Africa Corps is overstretched after redeploying some units to Ukraine and suffering from recruiting shortfalls.[13] The roughly 2,000 Russian troops in Mali are trying to protect the Malian capital, Bamako, while supporting counterinsurgency operations hundreds of miles away in central and northern Mali.[14] Russian Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-bek Yevkurov recently traveled to Burkina Faso and Niger in late November, promising to expand Russia’s small local contingents of 100–300 soldiers.[15] The 4,000 Wagner Group veterans operating in the Central African Republic (CAR) have not yet signed contracts with the Russian Ministry of Defense and are not integrated into the broader Africa Corps structure.[16] Syrian rebel advances south toward Homs threaten to cut off any Russian reinforcements or supplies sent to Tartus or the Hmeimim Air Base, although it is too soon to say how far the rebels can advance and whether they will be able to hold their gains.

A scenario in which the rebels toppled Assad would harm the Kremlin’s strategic objectives involving Africa and surrounding waterways, such as projecting power in the Mediterranean and Red Seas and threatening NATO’s southern flank. Russia’s activity in Libya and the Sahel supports its objectives of securing access in the Mediterranean and Red Sea, an undertaking that is heavily dependent upon Russia maintaining its naval base in Tartus. Tartus is Russia’s only formal overseas naval base, which it uses to project power into the Mediterranean for various purposes including ostensibly to counter NATO. Russia built up its presence in Tartus before it invaded Ukraine in 2022 to counter, deter, and monitor any NATO threats emanating from the Mediterranean, particularly aircraft carriers, among other things.[17] The base also links Russia’s Black Sea assets to the Mediterranean, although Turkey has severed this link for military vessels by closing the Turkish Straits under the Montreux Convention following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.[18]

Russia has been attempting to secure a naval base in Libya to expand its footprint and power projection around the Mediterranean. The Russian Ministry of Defense has intensified discussions for a Russian naval base in Libya, specifically Tobruk, since assuming control of the Wagner Group’s operations after the death of former Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin in August 2023.[19] Russia reportedly offered air defense systems and pilot training to Libya in exchange for the base, according to a 2023 Bloomberg report.[20] A Russian naval base in Libya would threaten Europe’s and NATO’s southern flank by helping support Russian activity in the Mediterranean Sea and potentially positioning a standing Russian force able to threaten NATO critical infrastructure with long-range cruise missile strikes from the sea.[21]

NATO has increasingly taken note of the unconventional and indirect threats that Russia has created along NATO’s southern flank through its efforts to replace the West in the Sahel. Russia lacks the capability and possibly the intent to immediately capitalize on these opportunities, however.[22] Russia has directly contributed to the drivers of trans-Saharan migration flows to Europe by displacing the West in the Sahel without effectively backfilling Western security assistance. Russia’s growing footprint in the Sahel has positioned it along key nodes on trans-Saharan migration routes.[23] Russian personnel in Africa have contact with traffickers but lack the capacity to heavily impact and weaponize these sprawling and decentralized networks beyond continuing to feed the instability that lies at the root of migration.[24]

Figure 3. Growing Russian Presence on Trans-Saharan Migration Routes in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr; Clingendael; Norwegian Center for Global Analyses.

Local affiliates of transnational terror organizations al Qaeda and the Islamic State have capitalized on the security vacuum to strengthen, increasing the latent threat these groups pose to Europe.[25] The strengthening of these groups is likely an unintended consequence of Russia’s strategy and not an objective of it, since these groups threaten Russia as well.[26]

Russia has long pursued a Red Sea port to protect its economic interests in the region and improve its military posture vis-à-vis the West in the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, but the loss of Tartus would diminish the utility of such a base.[27] The Kremlin increased support for Sudanese Armed Forces in 2024 in exchange for promises to revive a stalled 2017 deal for a Red Sea naval base capable of hosting 300 Russian service members and four ships.[28] Russian media has reported that a base in Sudan would primarily serve as a resupply and stopover hub to enable Tartus to transition from a resupply base to a multipurpose naval base, a goal Russia has previously outlined as a key element of its effort to bolster its Mediterranean power projection.[29] The Royal United Services Institute assessed that a naval base in Sudan would also help position Russia as a bulwark against maritime security threats in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean and serve as a logistics hub for its activity in Sudan.[30] The loss of Tartus would significantly limit the bandwidth of any future Sudan base to fill these various objectives, especially if it assumes Tartus’s role of projecting power into the Mediterranean.

Russia will face logistic challenges that will temporarily undermine its Africa operations if it loses its footprint in Syria. Russia’s bases in Syria have served as the primary staging ground for shipments from Russia that then go on to Libya and eventually sub-Saharan Africa.[31] Syria would presumably serve a similar purpose for any base in Sudan. The loss of Syria would immediately interrupt Africa Corps rotations and resupply efforts. Russia could seek to use its positions in Libya or Sudan as replacements, but it currently lacks formal agreements and facilities in both countries to adequately fill Tartus’s role. Domestic and international political backlash pose obstacles to Russia establishing another highly visible base in the short-term in either country.[32]

Figure 4. Africa Corps Logistics Network in Africa

Source: Liam Karr; Grey Dynamics; Jules Duhamel; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Assad’s collapse would damage the global perception of Russia as an effective partner and protector, potentially threatening Russia’s partnerships with African autocrats and its resulting economic, military, and political influence in Africa. Syria has served as the blueprint for the Russian “regime survival package.”[33] Russia offers military and population control support, economic engagement, information operations, and political cover in international bodies to keep autocrats in power and shield them from international pressure as part of this strategy.[34] Russia expands its military footprint and increases its economic and political hold over target governments as a result. This influence helps the Kremlin gain preferential economic access to mitigate sanctions and add allies in international institutions like the UN.[35] This support undermines democracy more broadly by insulating coup regimes from efforts to encourage a return to civilian rule, which erodes democratic values globally and thereby strengthens the Kremlin’s autocratic narrative.

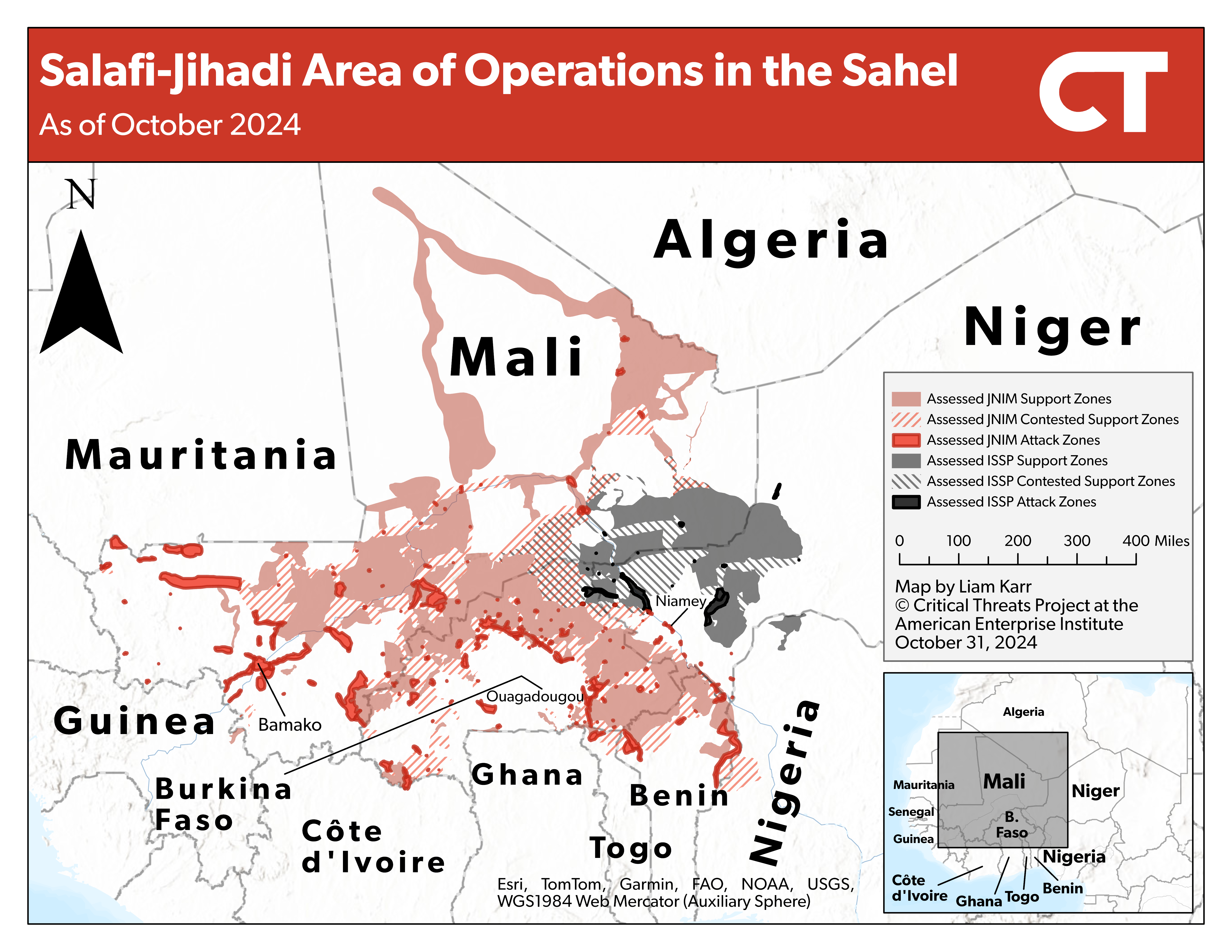

Russia has offered this package to several African allies, including the central Sahelian juntas that are facing an existential threat from strengthening Salafi-jihadi insurgencies. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), attacked the Malian capital, including an air base that houses Africa Corps personnel, for the first time in nearly a decade in September.[36] JNIM also attacked the suburbs of the Nigerien capital, Niamey, in October and is slowly encircling Burkina Faso’s capital.[37] A JNIM spokesperson gave a speech in November warning that JNIM had entered the “second stage” of its jihad and would soon begin capturing city centers.[38] CTP and others have assessed for over a year that ’JNIM and the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) are capable of attacking and overrunning major population centers across the Sahel but have decided not to do so in favor of siege-like tactics.[39]

Figure 5. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

[1] https://t.me/DIUkraine/4942

[2] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce313jn453zo

[3] https://www.businessinsider.com/russia-deploys-africa-corps-ex-wagner-fighters-kharkiv-uk-intel-2024-5

[4] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/08/29/les-paramilitaires-russes-de-la-brigade-bear-quittent-le-burkina-faso_6298336_3212.html

[5] https://t.me/rybar/62587; https://t.me/dva_majors/49167; https://t.me/rybar/62592; https://t.me/rybar/62613

[6] https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/12/first-sign-russian-navy-evacuating-naval-vessels-from-tartus-syria

[7] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/05/10/la-russie-accroit-sa-presence-en-libye-au-grand-desarroi-des-occidentaux_6232547_3212.html

[8] https://alleyesonwagner.org/2024/05/10/mediterranean-sea-objective-for-the-african-corps; https://www.svoboda.org/a/gotovitsya-boljshaya-zavarushka-voennaya-ekspansiya-rossii-v-livii/32939757.html; https://verstka.media/rossiya-naraschivaet-voennoe-prisutstvie-v-livii

[9] https://alleyesonwagner.org/2024/05/10/mediterranean-sea-objective-for-the-african-corps; https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/russia-backs-warlord-tighten-grip-africa-libya-mm93wc6nq

[10] https://alleyesonwagner.org/2024/05/10/mediterranean-sea-objective-for-the-african-corps; https://www.svoboda.org/a/gotovitsya-boljshaya-zavarushka-voennaya-ekspansiya-rossii-v-livii/32939757.html; https://verstka.media/rossiya-naraschivaet-voennoe-prisutstvie-v-livii; https://www.facebook.com/watch/?mibextid=I6gGtw&v=1819410208521809&rdid=MukHZvZxg50LERz1

[11] https://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/The%20Russian%20Military%E2%80%99s%20Lessons%20Learned%20in%20Syria_0.pdf; https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52811093; https://www.csis.org/analysis/moscows-next-front-russias-expanding-military-footprint-libya

[12] https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[13] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-august-2-2024-russian-blunder-in-mali-is-and-jnim-wreak-havoc-in-niger-jnims-border-havens-threaten-togo#Mali; https://t.me/rybar/59081; https://static.rusi.org/SR-Russian-Unconventional-Weapons-final-web.pdf; https://x.com/ChrisO_wiki/status/1780140057124364713

[14] https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[15] https://t.me/milinfolive/136414; https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[16] https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/02/07/africa-corps-wagner-group-russia-africa-burkina-faso; https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[17] https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/12/first-sign-russian-navy-evacuating-naval-vessels-from-tartus-syria

[18] https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/march/turkey-montreux-convention-and-russian-navy-transits-turkish

[19] https://www.wsj.com/world/africa/russia-seeks-to-expand-naval-presence-in-the-mediterranean-b8da4db; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-05/putin-s-move-to-secure-libya-bases-is-new-regional-worry-for-us; https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/italy-fears-russia-plans-nuclear-base-in-libya-qq5djndsh

[20] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-05/putin-s-move-to-secure-libya-bases-is-new-regional-worry-for-us

[21] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-may-16-2024-russian-outreach-across-africa-irans-uranium-aims-is-mozambique-continues-march#Libya; https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/may/kalibrization-russian-fleet; https://jamestown.org/program/russian-military-thought-on-the-changing-character-of-war-harnessing-technology-in-the-information-age; https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/rmsi_research/2; https://www.eastviewpress.com/the-naval-might-of-russia-in-todays-geopolitical-situation

[22] https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/5/pdf/240507-NATO-South-Report.pdf; https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_229634.htm; https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2024-04/060%20GSM%2024%20E%20-%20RUSSIA%20IN%20NATO%27S%20SOUTHERN%20NEIGHBOURHOOD%20-%20FRANCKEN%20REPORT_0.pdf

[23] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-special-edition-russias-africa-corps-arrives-in-niger-whats-next

[24] https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2024-04/060%20GSM%2024%20E%20-%20RUSSIA%20IN%20NATO%27S%20SOUTHERN%20NEIGHBOURHOOD%20-%20FRANCKEN%20REPORT_0.pdf

[25] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-areas-of-operation-in-the-sahel

[26] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68646380; https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/crgggwg158do

[27] https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russias-port-sudan-naval-base-power-play-red-sea; https://gulfif.org/slow-but-persistent-russias-overseas-basing-strategy-in-the-red-sea-and-the-gulf-of-aden; https://www.institute.global/insights/geopolitics-and-security/security-soft-power-and-regime-support-spheres-russian-influence-africa#conclusion-and-recommendations

[28] https://sudantribune.com/article285164; https://jamestown.org/program/will-khartoums-appeal-putin-arms-protection-bring-russian-naval-bases-red-sea; https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/15/russia-sudan-putin-east-africa-port-red-sea-naval-base-scuttled; https://jamestown.org/program/russia-in-the-red-sea-converging-wars-obstruct-russian-plans-for-naval-port-in-sudan-part-three

[29] https://www.mk dot ru/politics/2020/11/12/poyavlenie-rossiyskoy-voennoy-bazy-v-sudane-obyasnil-ekspert.html; https://tass dot com/defense/1222673

[30] https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russias-port-sudan-naval-base-power-play-red-sea

[31] https://www.voanews.com/a/middle-east_russia-expands-military-facilities-syria/6205742.html; https://alleyesonwagner.org/2024/05/10/mediterranean-sea-objective-for-the-african-corps; https://www.svoboda.org/a/gotovitsya-boljshaya-zavarushka-voennaya-ekspansiya-rossii-v-livii/32939757.html; https://verstka.media/rossiya-naraschivaet-voennoe-prisutstvie-v-livii; https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[32] https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[33] https://static.rusi.org/SR-Russian-Unconventional-Weapons-final-web.pdf;

[34] https://static.rusi.org/SR-Russian-Unconventional-Weapons-final-web.pdf; https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-68322230

[35] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-special-edition-russian-diplomatic-blitz-advances-the-kremlins-strategic-aims-in-africa

[36] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce8d996x1r0o

[37] https://www.theafricareport.com/366430/al-qaeda-affiliate-jnim-claims-attack-near-niamey; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-areas-of-operation-in-the-sahel

[38] https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1861478375694454964; https://x.com/lsiafrica/status/1861436414971216252

[39] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-june-27-2024-niger-reallocates-uranium-mine-is-strengthens-in-the-sahel-au-future-in-somalia#Sahel; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-september-19-2024-jnim-strikes-bamako-hungary-enters-the-sahel-ethiopia-somalia-proxy-risks#Mali; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-november-7-2024-niamey-threatened-boko-haram-fallout-in-chad-m23-marches-on-eastern-drc-somalia-jubbaland-tensions#Niger; https://www.institutmontaigne.org/expressions/effondrement-securitaire-au-mali-et-au-burkina-faso-que-peut-il-se-passer-anticiper-la-crise-travers