{{currentView.title}}

January 11, 2016

Iran's 2016 elections: The process, the players, and the stakes

The Iranian elections in February 2016 will be a critical turning point for the regime. The parliamentary election will be an indication of how willing the regime is to allow reformists to gain power, as well as a referendum on President Hassan Rouhani’s policies. The Assembly of Experts elected in February will almost certainly choose the successor of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The Islamic Revolution will likely either take a sharp turn or reject change and recommit to the current path for a considerable time.

The United States has a stake in these elections. A big victory for Rouhani and the reformers could indicate a mandate from the Iranian people and at least acquiescence by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the clerics, and the current Supreme Leader to open Iran up to the world more. U.S. policy-makers must avoid the temptation, however, to craft policies that attempt to affect Iran’s domestic political dynamics in the lead-up to the elections. The Guardian Council’s authority to vet candidates undermines the power of Iranian voters to select officials, thus weakening America’s ability to interfere indirectly in elections by cultivating popular support for a particular faction. The U.S. also runs a very high risk of undermining Rouhani’s government and its reformist allies by too ostentatiously seeking to help them. Leaks by senior officials about how the White House is gaming sanctions relief presumably to help Rouhani in the elections are thus damaging for many reasons.[1]

It is impossible to assess with any confidence what the effect of a Rouhani “victory” would be, moreover. Powerful conservative forces have already started to mobilize against reformists using rhetoric that suggests they might try a crackdown if they do not like the results of the election. The oppression following the 2009 elections generated one of the most aggressively anti-Western presidencies in Iran’s recent history.

We will know a lot about the significance of the elections even before they start simply by watching which of the 800 candidates for the Assembly of Experts and the more than 12,000 candidates for Parliament are allowed to run. Iran is a heavily managed democracy. Its constitution empowers the conservative-dominated Guardian Council to review the qualifications of candidates running in elections to Parliament, the presidency, and the Assembly of Experts. The Guardian Council therefore has the power to disqualify large numbers of candidates before they even have the chance to campaign. It has used this power in previous election cycles to disqualify reformist and moderate-inclined candidates disproportionately, and there is little reason to believe it will not do so again.

Parliament: The Check on the Executive Branch

Western analysts often underestimate the importance of elections and representative institutions within the Iranian political system. Iran is a theocracy in which the Supreme Leader is the ultimate decision-maker, and multiple unelected institutions such as the Guardian Council and the IRGC wield considerable influence, to be sure. These bodies are particularly important for foreign policy decision-making, where, understandably, most of America’s attention is fixated. Iranian elections are nevertheless critical inflection points for the regime as a whole because they provide an opportunity to reframe and shift Iran’s domestic political climate. Parliamentary elections are often proving grounds for future presidential candidates and other individuals who hope to champion change within the political system.

Parliament has a number of important powers in the Iranian political system, at least on paper. In addition to drafting legislation for approval by the Guardian Council, Parliament is tasked with oversight over the President’s cabinet, approving the annual budget presented by the President, and ratifying international treaties.[2] In practice, Parliament’s powers in the policy process are curtailed by other institutions, most notably the Guardian Council, which reviews all legislation to ensure conformity with its interpretation of Islamic law. Iran’s weak party system also breeds intense factionalism to the detriment of the legislative process within Parliament.

Parliament is also a tool for shaping the domestic political climate. The conservative and hardline parliamentarians who dominate Parliament have used the podium to relentlessly attack the administration’s policies, pass legislation intended to constrain Rouhani’s policy choices, and question and sometimes initiate impeachment proceedings for members of Rouhani’s cabinet.[3] According to Iranian news outlets, parliamentarians have submitted over 8,000 formal letters to the Rouhani administration on various policy subjects.[4] Parliament has, in particular, taken a vocal approach to intervening in Rouhani’s foreign policy adventures through the National Security and Foreign Policy Parliamentary Commission and then briefly through a commission tasked to review the nuclear deal.[5]

Rouhani and his pragmatic and moderate allies have much to gain in the next elections if they can pick up more seats and help insulate the administration from parliamentary criticism. Rouhani has been able to fend off Parliament’s attacks with varying degrees of success, mostly through the help of Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani, who has faced criticism from hardliners and his fellow conservatives over this perceived alliance.[6] Larijani’s role as Speaker is not a given, however, as he must stand for reelection with the new Parliament. If President Rouhani’s pragmatic allies lose seats in Parliament or even the speakership, Rouhani will face an even more combative Parliament in advancing his agenda ahead of the 2017 presidential elections.

Assembly of Experts: The Kingmakers

The Assembly of Experts is generally considered to have a largely ceremonial role in the Iranian political system.[7] That will likely change in the near future. The Assembly of Experts has the sole constitutional authority to appoint a new Supreme Leader, even though other powerful institutions, namely the IRGC and the Supreme Leader’s Office, will likely play a significant role in this process as well. Articles 107 and 111 of Iran’s Constitution charge the Assembly of Experts with the power to elect, supervise, and dismiss the Supreme Leader, although the extent to which it supervises the Supreme Leader has been hotly debated in the past month.[8] Members are elected for roughly eight-year terms.[9] The Assembly of Experts chosen in this upcoming election cycle is thus likely to make the single most important appointment in the Islamic Republic. It will almost certainly be called upon to choose the successor to the current Supreme Leader, who is 76 years old and has a recent history of medical issues.[10]

The Assembly of Experts also has the potential to transform the power structure of the Islamic Republic itself. Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, an Assembly of Experts member and the current chairman of the Expediency Discernment Council -- an important body that mediates disputes between Parliament and the Guardian Council when the latter vetoes legislation -- reignited debate over the possibility of choosing a “Leadership Council” instead of a single Supreme Leader during an interview in mid-December. While he stated that the Assembly of Experts is creating a list of “individuals who have the qualifications” to become the Supreme Leader, he also emphasized that the Assembly of Experts was considering three potential successors to the office of the Supreme Leader when Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini passed away in 1989.[11] Both the 1979 Constitution and its amended version in 1989 allow for a Leadership Council in a transitional period before the final selection of a new Supreme Leader.[12] Rafsanjani was likely advocating a permanent council of leaders, however, which he had also supported more explicitly in speeches in 2003 and 2008.[13]

The fierce opposition to Rafsanjani’s comments underscores the unlikelihood of an Assembly of Experts with a composition similar to the current one choosing a Leadership Council instead of a single Supreme Leader.[14] The debate surrounding the idea of a Leadership Council nonetheless highlights the importance of the conservative establishment controlling the makeup of the Assembly of Experts. Rafsanjani has put on the table not merely the question of who the next Supreme Leader will be, but whether there will be a single Supreme Leader at all. He has thus added even more incentive for Iran’s conservative establishment in the Guardian Council to use the vetting process to disqualify candidates who are perceived to be at odds with the Supreme Leader’s camp. As Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, one of the Assembly’s most vocal hardliners, noted, the moderates would be successful “even if they achieve a minority” in the Assembly of Experts.[15]

“Supervising” the Elections

The Guardian Council is ultimately responsible for endorsing the final list of qualified candidates for both the Assembly of Experts and Parliament, even though the Interior Ministry, whose head is a member of the President’s cabinet, is also involved at the preliminary stages of reviewing candidates for Parliament. The Guardian Council is generally perceived as being aligned with Khamenei, which is not surprising, given that the Supreme Leader appoints half of the Guardian Council’s members directly and the other half indirectly.[16] The Guardian Council’s current secretary is Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati, a vehemently anti-reformist cleric.

Iran’s election laws grant the Guardian Council sweeping powers to weed out candidates arbitrarily. A handful of qualifications for parliamentary and Assembly of Experts candidates can be found in the electoral laws, but they are ambiguous. For example, parliamentary candidates must possess a “practical belief” in the “sacred order” of the elections and be loyal to the “absolute rule” of the guardianship of the jurist.[17] The Guardian Council’s powers to disqualify candidates are strengthened by the notion of “approbatory supervision,” a poorly defined concept that grants the Council absolute authority to disqualify candidates on arbitrary grounds outside of the listed qualifications in the electoral laws.[18] In essence, this process allows the Guardian Council -- and by extension the Supreme Leader -- to eliminate any candidates who are perceived to be at odds with the status quo.

The Guardian Council has wielded this power quite extensively during recent election cycles, predominantly discriminating against reformist and moderate-inclined candidates. The Guardian Council’s aggressive vetting process is perhaps best exemplified in the case of Rafsanjani himself, whom the Council barred from running in the 2013 presidential election ostensibly on the grounds of his old age.[19] Rafsanjani’s disqualification came as a shock, given his credentials as a former president and parliament speaker. Rumors are already circulating that Rafsanjani will be barred from running for the Assembly of Experts, despite the fact that he is currently a member.[20]

The Vetting Process: A Lesson in Managed Democracy

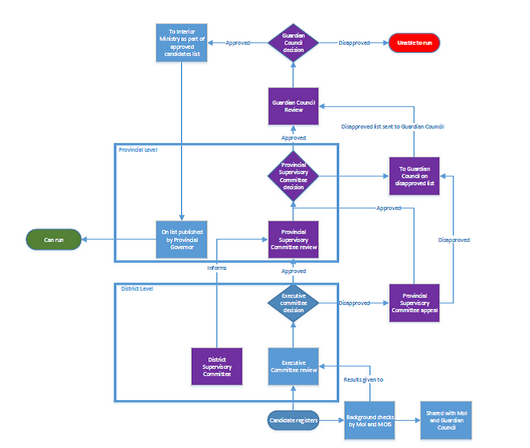

Iran’s electoral system is extremely complex. The bureaucracy tasked with vetting electoral candidates for Parliament is divided along local, provincial, and national lines, and it is characterized by parallel lines of authority and information-flow between the Interior Ministry and the Guardian Council.[21] The process ultimately hands all decisions about which candidates can run to the Guardian Council.

Iran’s parliamentary elections involve three distinct rounds of qualification review, the timelines for which are provided below. Initially, the Interior Ministry submits a national list of prospective candidates to relevant central agencies to begin conducting background checks, including the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Intelligence and Security.[22] The results of these checks must then be shared with the Interior Ministry and the Guardian Council within five days.[23] The Interior Ministry must then pass on the findings to Executive Committees, which are comprised of local representatives tasked with implementing the first round of qualification review.[24]

The Executive Committees are chaired by the county or district governor (appointed by the Interior Ministry) and consist of a few local officials and several citizens of the district.[25] The Executive Committees review the candidate’s qualifications, inform candidates of their decision by January 5, and send the entire vetted list of candidates -- including all candidates who have been disqualified -- to the Provincial Supervisory Boards, which are managed by the Guardian Council.[26] Candidates can submit an appeal to the Supervisory Boards at this stage if they have been disqualified by the Executive Committees. This process has been completed, and initial reports show that a very high proportion of candidates who registered have passed the first stage of vetting.[27]

The Provincial Supervisory Boards conduct their reviews from January 10-16.[28] These institutions vet the lists of candidates, review any accompanying documentation from the Executive Board review, and hear any appeals from disqualified candidates. The Provincial Supervisory Boards also use information collected by local Guardian Council representatives, the so-called District Supervisory Committees. The Guardian Council’s supervisory infrastructure in the elections can therefore rely upon a separate stream of information to circumvent the Ministry of Interior’s review process in the Executive Committees.[29]

Guardian Council Spokesman Nejatollah Ebrahimian remarked on December 28 that that the Guardian Council’s “representatives” had already begun to record the “behavior” of electoral candidates.[30] This process ensures that the Guardian Council bureaucratic superstructure can effectively override the decisions of the Interior Ministry. One senior Iranian official, the IRGC Cultural Deputy no less, highlighted the potential source of tension between these two institutions:

The Interior Ministry must show how much it will adhere to the Constitution…If the Executive Committees do not consider these issues in their review, it is clear that [the Interior Ministry] does not adhere to the Constitution…If the Interior Ministry does not act according to its legal duty, the Guardian Council must act. We cannot let Parliament be occupied by infiltrators along with counter-revolutionaries.[31]

Once finished, the Provincial Supervisory Boards will send the entire vetted list of candidates to the Guardian Council for the final stage of the vetting process.

The Guardian Council conducts its review from January 17 to February 5.[32] It will review the qualifications of the remaining candidates and confirm or reject the disqualifications issued from the Provincial Supervisory Boards, the Executive Committees, or both.[33] The Guardian Council will disclose to the electoral candidates a finalized list of candidates and supporting legal evidence by February 6.[34] The Guardian Council will then investigate and review any complaints and submit a finalized list of candidates to the Interior Ministry by February 16, which will then be published by provincial governors by February 17.[35] The full timeline for these stages of the vetting process in the February 2016 parliamentary elections follows below.

First round of review for parliamentary candidates:

1.December 26 – January 4: Executive committees examine candidates’ qualifications.

2.January 5: Executive committees inform candidates about the results of their review.

3.January 6 – 9: Candidates who have been disqualified in this first round of review can protest their disqualification to provincial supervisory boards.

Second round of review for parliamentary candidates:

4.January 10 – 16: Provincial supervisory boards conduct investigations into the disqualification of candidates who have filed complaints. Provincial supervisory boards then send a finalized list of vetted candidates to the Guardian Council.

Third round of review for parliamentary candidates:

5.January 17 – February 5: The Guardian Council reviews and creates another list of qualified candidates.

6.February 6 – 8: Candidates whose qualifications have been dismissed by the Guardian Council can file a complaint to the Guardian Council.

7.February 9 – 15: The Guardian Council investigates the complaints.

8.February 16: The Guardian Council submits a finalized list of candidates to the Interior Ministry.

9.February 17: Provincial governors publish the finalized list of candidates.

10.February 18 – February 24: Candidates campaign.

11.February 26: Election Day.

Elections for the Assembly of Experts are less complex, at least on paper. The Guardian Council appears to be primarily responsible for determining the qualifications for candidates in the Assembly of Experts, which are both religious and political in nature according to law. Candidates must show that they can interpret Islamic law, display a “belief” in the Iranian political system, and do not possess an “anti-political or social background.”[36] The timeline for the Assembly of Experts elections in February is as follows:

1.January 5: The Guardian Council administered a written exam to assess candidates’ qualifications in Islamic jurisprudence. Current members of the Assembly of Experts who are running for reelection or individuals who passed the test in previous elections are not required to take the exam. The Guardian Council has also stipulated that candidates who do not have a seminary education are not allowed to take the test and are therefore disqualified from participating in elections.[37] After the Guardian Council permitted 537 of the 801 registered candidates in the ongoing elections to take the exam this year, only 400 candidates ultimately chose to take it.[38]

2.January 26: The Guardian Council will tell candidates the results of their preliminary review by this date.[39]

3.January 31 – February 9: The Guardian Council will review any appeals and release the finalized list to the Interior Ministry, which will then publish it.[40]

4.February 11 – February 24: Candidates campaign.[41]

5.February 26: Election Day.

Guardian Council members have signaled that the Guardian Council will be rigorously reviewing religious qualifications in this cycle. One such member, Ayatollah Mohammad Momen, noted on December 15 that simply possessing the rank of mujtahid “is not enough for the Assembly of Experts” and added that “the religious knowledge of candidates must be proven to Guardian Council members.”[42] A mujtahid is an Islamic scholar recognized as capable of interpreting legal issues untouched by the Quran, and this rank has generally represented the standard for candidates running for the Assembly of Experts. Momen’s comment indicates that the review of members’ religious qualifications will continue at least as stringently as in the past.

The View from the Guardian Council

Vetting procedures are under unusual strain in the current election cycle. Iranian news outlets reported that 12,123 candidates registered for the parliamentary elections – almost triple the number of candidates in the previous parliamentary elections in 2012.[43] The number of candidates in the elections for the Assembly of Experts has nearly doubled from 493 in the last election to 801 this year, nearly nine times the total number of available seats in the body.[44]

Tehran’s hardliners have reacted to the increase in the number of candidates with unease. The large number of candidates -- many of whom are reportedly newcomers to the Iranian political scene -- has fueled hardliners’ fears that reformist-inclined individuals are trying to expand their influence. To an extent, their fears are justified. A sizeable number of parliamentary candidates have documented ties to the reformist camp, particularly President Khatami’s administration.[45] There are also a number of moderate candidates for the Assembly of Experts who might challenge the hardliners’ hold on the Assembly of Experts.[46] Guardian Council Secretary Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati cited the increase in candidates and noted:

Do all 800 people who registered for the Assembly of Experts consider themselves clergymen? Aren’t some of them incapable of clearly reading even one phrase in Arabic, the Quran, or a single book of religious jurisprudence?…It is the same for those who registered their candidacies for Parliament![47]

Senior officials in the Guardian Council have signaled their readiness to disqualify reformists, or the so-called “seditionists,” who might challenge the status quo. A key factor in the Guardian Council’s review appears to be any alleged links to the reformist Green Movement protests in 2009, which officials often call simply “the sedition.” Several days after the registration period closed, the Guardian Council’s spokesman cast a wide umbrella over unacceptable acts for candidates by stating bluntly that they must not have “partnered or cooperated in the illegal acts that occurred” during the Green Movement protests.[48] Guardian Council Secretary Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati also reaffirmed the Guardian Council’s intent to disqualify individuals linked to the Green Movement and lauded vetting procedures as “the right of the people” due to its ability to weed out “unqualified” candidates; he praised the Iranian people’s ability to “put out the fires of the sedition” as well.[49]

The hardliners have expressed concern that the increase in candidates will strain the Guardian Council’s ability to conduct a “just and fair” qualifications review during the “severe time restrictions” of the elections.[50] Their concerns are likely driven by political calculations. Senior officials know that the mass disqualification of candidates will likely come with a sizeable political cost if the review process is perceived as rushed. Moderate and pragmatic-minded politicians — not to mention President Rouhani -- have repeatedly warned that the vetting process, while important, must not prevent elections from being “healthy and lively.”[51] Khamenei also has his own priorities for the elections. In addition to ensuring that Rouhani does not become too powerful, he likely also seeks to avoid any repeat of the 2009 election protests and the resulting controversy that damaged the regime’s legitimacy.

There is also the potential that Rouhani and his allies might push back against any mass disqualification of candidates. Rouhani publicly criticized the Guardian Council’s interference in the elections during a speech on August 19, presumably in an effort to curtail any extensive vetting procedures. Rouhani claimed that that the Guardian Council should be the “eyes” rather than the “hands” in elections, although his comments were quickly condemned by nearly the entire top strata of Iran’s political elite, including prominent Guardian Council and Assembly of Experts members, the Judiciary Head, IRGC Commander Major General Mohammad Ali Jafari, and the Supreme Leader himself. [52] Khamenei lectured, “The Guardian Council is the regime’s discerning eye in elections…The Guardian Council’s oversight in the elections is approbatory and effective. This is their right, it is their legal right, it is their rational right; some objections [to the Guardian Council’s rights] are gratuitous.”[53]

Rouhani has toned down his comments on the Guardian Council since his August 19 challenge. During a speech on December 7, Rouhani opined that he recognizes and supports the Guardian Council’s role as defined in the Constitution, a veiled criticism of the Council’s increasingly aggressive vetting procedures in recent years.[54] He added that his administration will cooperate with the Guardian Council in order to hold “open and competitive elections” and will investigate any “administrative violation.”[55] Rouhani’s efforts to force greater accountability upon the election process are unlikely to have a great impact on the final decision-making process. The nearly unanimous condemnation of Rouhani’s August 19 remarks illustrates that the prevailing opinion among Tehran’s political elite is overwhelmingly in support of the Council’s extensive authority to disqualify candidates -- and against any efforts to curtail it.

Conclusion

It is generally difficult to predict Iranian elections. All signs nonetheless suggest that the Guardian Council will ensure that the Assembly of Experts does not stray far from Khamenei’s camp. The Council will also undoubtedly prevent at least some reformist-inclined candidates from running for Parliament. It remains to be seen whether the Guardian Council will also use the vetting process to disproportionately disqualify Rouhani’s pragmatic allies in Parliament. If so, Rouhani will face an even more intransigent Parliament when trying to advance his agenda before the 2017 presidential elections.

In the meantime, Washington must avoid the temptation to play factional politics in Tehran by trying to curry political support for a particular faction or politician. The structure of the election process offers a clear example as to why. The key power centers in Tehran are able to dilute and manage grassroots pressure through a complicated bureaucracy that reaches all the way down to the local level. America’s perceived support of a politician or bloc would likely only strengthen public support for the opposing faction, given the dynamics of Iran’s political culture.

The moderates in Tehran also face considerable challenges after the Guardian Council’s vetting process. Rouhani’s allies will likely rely on the administration’s economic and foreign policy record to muster public support during the elections, but Rouhani’s record as “economic savior” has been under fire in recent months due to the country’s deepening economic slowdown.[56] Rouhani’s post-nuclear deal economic policies, and what they might do to entrenched economic interests in the country, have also been divisive, even among Rouhani’s own allies.[57] In addition to these policy challenges, moderate candidates for both Parliament and the Assembly of Experts have no strong organizational structure and face considerable and already apparent pressure from the regime.[58]

Given these realities, simply gaining a foothold in the Assembly of Experts and increasing the number of their seats in Parliament would be a realistic victory for the moderates. This alone might leave Rouhani and his allies better positioned in the factional balance of power that dominates decision-making in Tehran.