{{currentView.title}}

July 13, 2020

Iran’s entrenchment of strategic infrastructure in Syria threatens balance of deterrence in the Middle East

Contributors: John Dunford, Katherine Lawlor, Brandon Wallace

Iran is realigning its force posture in Syria to retain and expand its deterrence, freedom of action, and leverage with the US, Israel, and Russia. The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) began moving some of its forces in Syria away from the front lines in the spring of 2020 while expanding and consolidating its footprint in eastern Syria. This shift offers Tehran more secure bases more directly under its control to threaten Israel and the US as instability risks some of its positions in Iraq and Lebanon.

The IRGC has increased efforts to establish advanced weapons capabilities and command infrastructure in Syria since early 2019. Iran has been building a military and proxy network in Syria since the Syrian civil war broke out in 2011. Iranian and Iranian-backed forces have since expanded their military presence into an arc stretching from eastern Syria, along the Iraqi border, through central Syria to south and southwestern Syria, along the Israeli and Lebanese borders.

Iran’s strategic presence has allowed Iranian and Iranian-backed forces to move troops and equipment from Iraq to Lebanon. Iran increasingly sees Syria as more than a safe passage to Lebanon, however. Iran’s expanded presence in southern Syria since 2018 has given Iranian forces direct access to Israel not reliant on positions in Lebanon.

Iranian forces have been constructing a new heavily fortified base at Abu Kamal in eastern Syria since the summer of 2019. Iran has been expanding its military presence in Deir ez Zor province since 2017, when an Iranian, Russian, and Syrian Arab Army offensive took control of the area from the Islamic State. The Abu Kamal base is the first military facility of this scale that Iranian forces have built in Syria. The base has a new level of fortification, featuring a 400-foot-long underground tunnel and housing facilities for thousands of troops. Its underground storage facilities and large personnel encampment represent a long-term effort to entrench Iranian-controlled military assets and personnel in Syria.

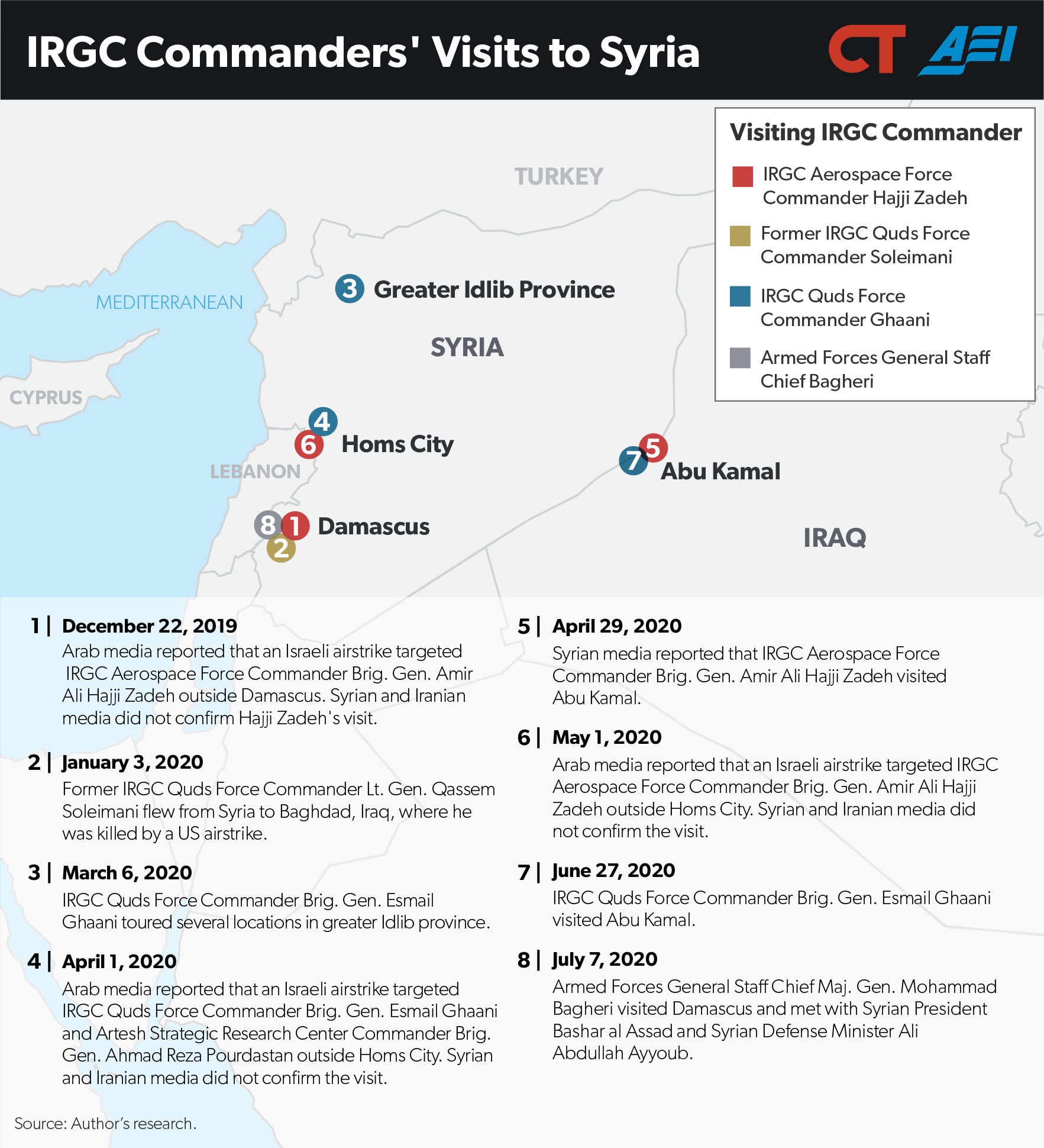

The newly outfitted Abu Kamal base in Deir ez Zor province along Syria’s border with Iraq has become an increasingly important command and control node over the past few months. Lebanese Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah confirmed Abu Kamal’s growing importance in a *speech on May 13, acknowledging that Iranian-backed fighters were moving from the front lines to Abu Kamal. IRGC Aerospace Force Commander Amir Ali Hajji Zadeh and IRGC Quds Force Commander Brig. Gen. Esmail Ghaani, Lt. Gen. Qassem Soleimani’s successor, visited Abu Kamal in April and June, respectively. At least 400 fighters from Liwa al Muntadhir, an Iranian proxy Shia militia group from Iraq, reportedly deployed to Deir ez Zor province in early March. Iran’s most trusted Iraqi Shia militia groups have been active in Syria alongside a host of Iranian-backed Pakistani and Afghan foreign fighters for many years, but a new deployment to Syria is rare. A growing troop presence in Abu Kamal likely indicates Iranian forces intend to expand a newly fortified strategic command and control node along the Iraq border.

The base will likely also give Iran a safe platform to expand advanced weapons capabilities in Syria. Hajji Zadeh, who is responsible for the development of Iran’s missile and drone programs, reportedly visited Syria in the past six months. Hajji Zadeh has been involved in technology sharing abroad, visiting Venezuela at least once likely to share drone technology. Arab media has reported that Hajji Zadeh visited various locations in Syria several times since December 2019.[i] Syrian media confirmed Hajji Zadeh visited Abu Kamal at the end of April 2020. Israeli airstrikes additionally targeted *Safira and *Maysaf in May and June, locations linked to missile and chemical weapons development, suggesting that the Iranians were bringing new strategic capabilities to those locations.

Iranian consolidation to eastern Syria likely results from a confluence of factors. Competition with Russia to solidify economic and political advantages has grown as Syria potentially enters a reconstruction phase. Iraq’s turbulent political situation since the fall of 2019 has challenged Iran’s military and political influence there. Economic collapse in Lebanon confronts Iran’s most important proxy, Lebanese Hezbollah, with challenges that may reduce its reliability and even its own stability in Lebanon. Israel has steadily increased the frequency and scale of its aerial attacks on Iranian infrastructure in Syria. The Iranian regime, lastly, faces unprecedented economic strain caused by the US maximum pressure campaign, mounting stagflation (inflation without economic growth), and the COVID-19 pandemic. All these factors likely make establishing a stable and secure Iranian base in eastern Syria, not dependent on Iranian positions or proxies in Lebanon or Iraq, attractive.

Instability in Iraq and Lebanon makes Syria especially important to Tehran. Syria has become a more important base to house advanced weapons capabilities and regional command and control centers due to the uncertainty faced by Iranian allies in Iraq and Lebanon.

Iranian repositioning in Syria is likely a partial hedge against political change in Iraq. Iraq’s Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi submitted his resignation in November 2019 after nearly two months of anti-government protests and a bloody security crackdown. Months of political instability followed as Iraqi politicians sought to balance US and Iranian influence to pick a new candidate for prime minister. The new prime minister, Mustafa al Kadhimi, has already shown a proclivity to side with the US and has conducted dramatic and unusual efforts to rein in Iranian militia proxies. An expanded Iranian force presence along the Iraqi border in Syria gives Iran’s proxy militias in Iraq some insurance against such efforts.

The March 2020 US withdrawal from its base on the Iraq-Syria border at al Qaim facilitates this insurance policy. US forces at al Qaim could have observed and interfered with Iranian ground movements to and from Abu Kamal and could have reinforced Iraqi troops that Kadhimi might have used to disrupt such movements should he so choose. The withdrawal of those forces has made Iran’s ground route to Abu Kamal and the rest of Syria more secure, likely giving the Abu Kamal base and Iran’s positions in eastern Syria even greater importance than they previously had.

Lebanon’s devolving political and economic conditions additionally make securing strategic depth in Syria more important. Lebanon faces instability on a scale not seen since the end of its civil war. Protests against government mismanagement and ineffectiveness erupted in Lebanon in the fall of 2019, quickly taking on anti-Iranian and anti-Hezbollah overtones.

Hezbollah and the rest of the Lebanese government were unable to address the grievances or manage the protests. The accession of Hezbollah ally, Hassan Diab, to the premiership in January 2020 has deprived the group of the facade from behind which it had been developing its political influence since 2009. Lebanon’s currency has devalued by more than half in June alone, causing exorbitant food prices and increased blackouts. The collapse of Lebanon’s economy and continued corruption in the Hezbollah-aligned government, further threatens Hezbollah’s position, particularly since the group has now assumed more formal responsibility for the country’s fate.

These developments in Lebanon likely change Iranian leaders’ calculus when considering whether they can use Hezbollah’s weapons arsenal to threaten or attack Israel. The resulting conflict with Israel could restabilize Hezbollah in Lebanon as happened after the 2006 war, but it could also trigger the collapse of the Lebanese state and the unraveling of Hezbollah’s control over it. Even if Iran’s leaders are willing to run that risk—and can convince or cajole Hezbollah into taking the same view—the risk itself could still undermine Hezbollah’s deterrent effectiveness in the eyes of Israeli leaders.

Advanced weapons capabilities in Syria allow Iran to sidestep the new complexities its allies in Lebanon face. Iranian forces have tried to launch *weaponized drones from Syrian territory to target Israel previously. Neither the US nor Israel retaliated against those attacks by hitting targets in Lebanon on a large scale, of course, establishing the precedent that Iran risks only the forces in Syria by conducting attacks from Syria.

The expansion of the IRGC footprint in eastern Syria can also help mitigate command and control challenges in the “Axis of Resistance” after Soleimani’s death. Soleimani had personal relationships with leaders throughout Iran’s Axis of Resistance that the new Quds Force commander, Ghaani, cannot maintain in the same way. Ghaani does not speak fluent Arabic and had focused on non-Arab Quds Force efforts, leaving him with fewer personal connections in the Levant. Soleimani, whom Iran’s supreme leader called a “living martyr,” had a unique status among IRGC partners in the Levant—a standard Ghaani cannot meet.

The death of Kataib Hezbollah leader Muhandis, killed in the Soleimani strike, also challenges Iran’s influence and control over militia groups in Iraq. Muhandis, though an Iraqi politician and commander, was an Iranian citizen who spoke Persian, making him a pillar of Iranian influence in Iraq. Muhandis, like Soleimani, was also a revered figure among Iran’s most ideologically committed proxies in Iraq. Kataib Hezbollah in particular has borne a heavy cost for Iran, taking multiple US and Israeli airstrikes and becoming a target for US sanctions. Some of its members may have demanded a bloodier retribution for Soleimani and Muhandis’ death than the pragmatic approach Iranian leaders instead adopted. Kataib Hezbollah announced that Kadhimi’s nomination for prime minister in April was a declaration of war even as known Iranian Quds Force officials and former Iranian ambassadors to Iraq *publicly *endorsed it. Iranian English language media outlets *falsely reported that Kataib Hezbollah supported Kadhimi, possibly to cover up a lapse in command and control. This unusual divergence in messaging likely reflected real tensions. Tehran’s commitment to increasing strategic assets in eastern Syria directly controlled by the IRGC may give the IRGC greater ability to manage such tensions and more directly oversee its proxies in Syria and Iraq.

Iran’s consolidation in eastern Syria also gives Tehran leverage as tensions with Russia rise. Iran is escalating efforts to build strategic infrastructure likely in response to tension between Russia and Bashar al Assad, Iran’s allies in the Syrian civil war. Russian media published rare articles *criticizing Assad in April, emphasizing corruption and the failing economy. Iranian media subsequently *implied that Russia has condoned Israeli airstrikes on Iranian-backed, pro-Assad forces in Syria, a previously taboo topic for Iranian media. Russia and Iran have even engaged in tactical struggles for control over troops in southeastern and southern Syria over the past few months.

Moreover, Iran’s relationship with Assad has itself been challenged recently. An Iranian official fiercely *denied rumors that Iran and Russia had a secret deal to pull support for Assad in May. The rumors and anti-Assad regime protests in southern Syria criticizing the presence of Iranian militias, which Russia has shown little interest in subduing, may also stoke tensions. The worsening economic conditions in Syria further destabilize the country and could strain the Assad-Iran relationship even more, particularly as Tehran faces its own economic crisis and Iranian officials pressure for a return on their $30 billion investment in the country.

Advanced weapons and command infrastructure give Tehran assets in Syria to leverage during Syria’s reconstruction even if Syria transitions to less Iran-friendly leadership. Expanded force presence in Abu Kamal offers military leverage over oil assets in surrounding Deir ez Zor province in the medium term. The Syrian Parliament and Oil Ministry *drafted legislation giving Iran oil rights in Abu Kamal in May, the first step toward Iran’s first major oil deal in the country. Iran and Russia continue to battle over rights to strategic naval and land bases, phosphate and oil exploration rights, and major reconstruction projects. Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah officials have indicated they *value the Abu Kamal-al Qaim border crossing as a transit point for longer-term economic trade in postwar Syria. New economic challenges to Iran from the US maximum pressure campaign and the COVID-19 pandemic and to Hezbollah-controlled Lebanon from economic collapse incentivize Iran to solidify economic interests in Syria.

Iran’s campaign to increase weapons capabilities directly under IRGC control and entrench command and control capabilities in Syria will have a lasting effect on the balance of deterrence in the Middle East. The regime is reacting opportunistically to regional political and economic challenges to safeguard its long-term investment in Syria and expand strategic deterrence in the region. Protests and the subsequent unrest in the key Iranian strongholds of Lebanon and Iraq since the fall of 2019, which sparked similar unrest inside Iran in November 2019, posed a near existential threat to Iran’s strategic depth and consequently the Islamic Republic itself. The instability in Iran’s key theaters incentivized regime decision makers to renew and expand strategic assets and deterrence. Iran additionally faces new pressure amid economic hardship to secure economic incentives from its near decade-long involvement in Syria. Iranian forces are building up advanced weapons capabilities to have a new level of fortification against enemy attacks that can be used to strike at multiple points in the Levant. The newly fortified Abu Kamal compound will be a key strategic base for Iran to expand its military, economic, and political influence in the region and maintain its strategic depth.

Iranian leaders may be more willing to exercise their strategic capabilities in Syria in the fall if the UN arms embargo does not lift in October and the US president-elect in November does not demonstrate a commitment to reducing US sanctions. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s increasing isolation and a new hard-line-majority Iranian Parliament could also contribute to more aggressive regime calculus in coming months. Economic pressure and regional instability have not stopped Iranian efforts to militarily entrench in Syria in the past year. Iran instead has increased efforts to secure strategic depth by building new and more advanced military facilities in Syria. US policymakers must reckon with the leverage and capabilities those facilities give the Islamic Republic going forward.

[i] Arab media *reported that Israeli airstrikes targeted Hajji Zadeh in Damascus on December 22, 2019. IRGC Spokesman Brig. Gen. Ramazan Sharif *immediately denied reports Hajji Zadeh was killed in the strike, but Hajji Zadeh did not speak or *appear on camera to deny reports in December until four days later, possibly indicating Hajji Zadeh was indeed in Syria at the time of the Israeli strike. Similar Arab reporting suggested Hajji Zadeh was also *targeted just outside western Homs city in western Syria on May 1 a few days after Syrian media confirmed that Hajji Zadeh was in the border city of Abu Kamal. Syrian and Iranian media did not confirm reports Hajji Zadeh was in Homs in May 2020 or Damascus in December 2019.