{{currentView.title}}

November 20, 2024

Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

You can read regular in-depth analyses on ISSP and JNIM in the Sahel in CTP’s weekly Africa File.

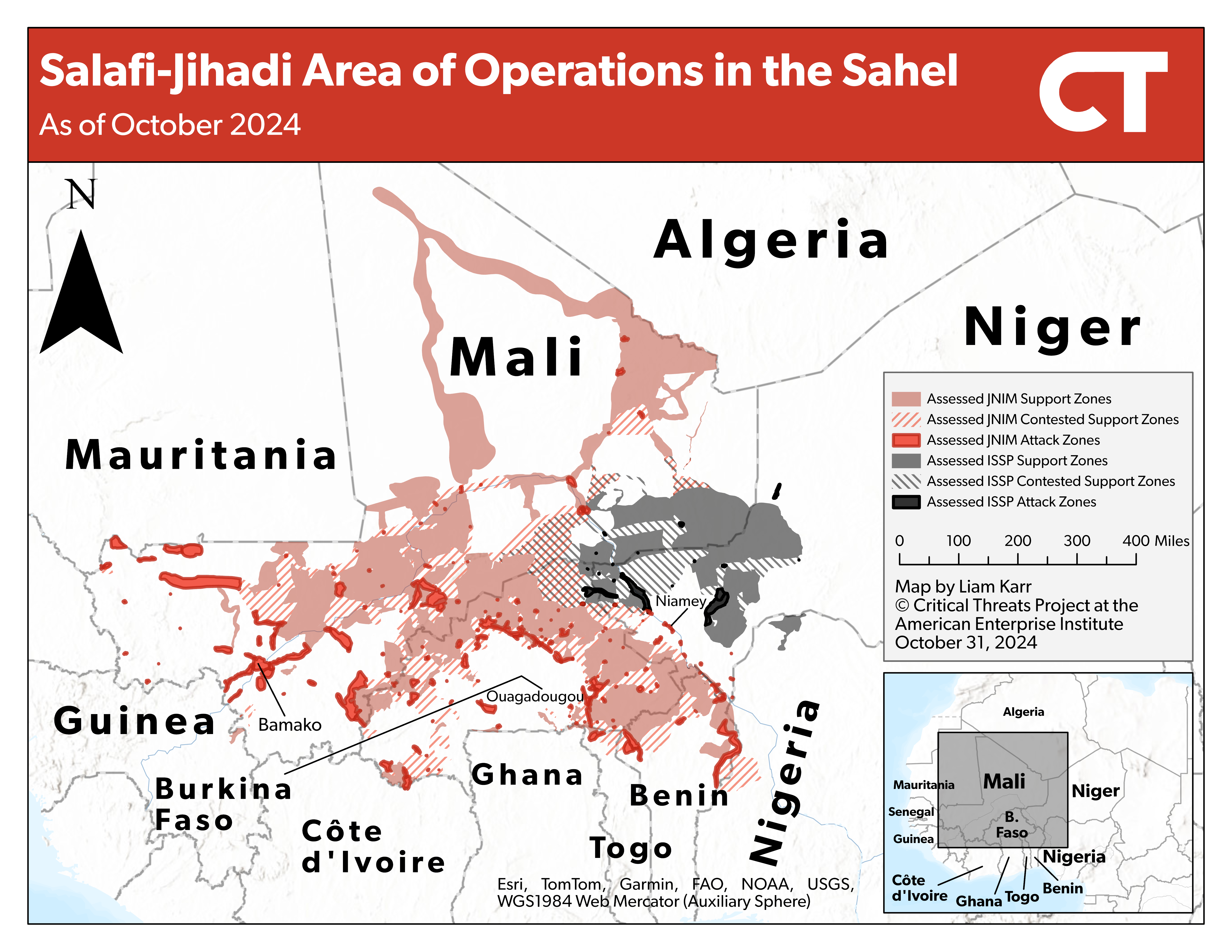

Al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates are expanding rapidly in West Africa’s Sahel region, taking advantage of long-running grievances and state incapacity. The predominant groups are Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), which is an affiliate of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISSP), previously known as Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. Salafi-jihadi activity first spiked in the Sahel when AQIM and local partners co-opted a rebellion in northern Mali and attempted to establish an emirate. A French-led intervention rolled back this initial takeover, but Salafi-jihadi groups have continued to proliferate and expand in the past decade, particularly throughout central Mali and Burkina Faso. JNIM and ISGS have also begun to operate in the border regions of the Gulf of Guinea states in recent years.

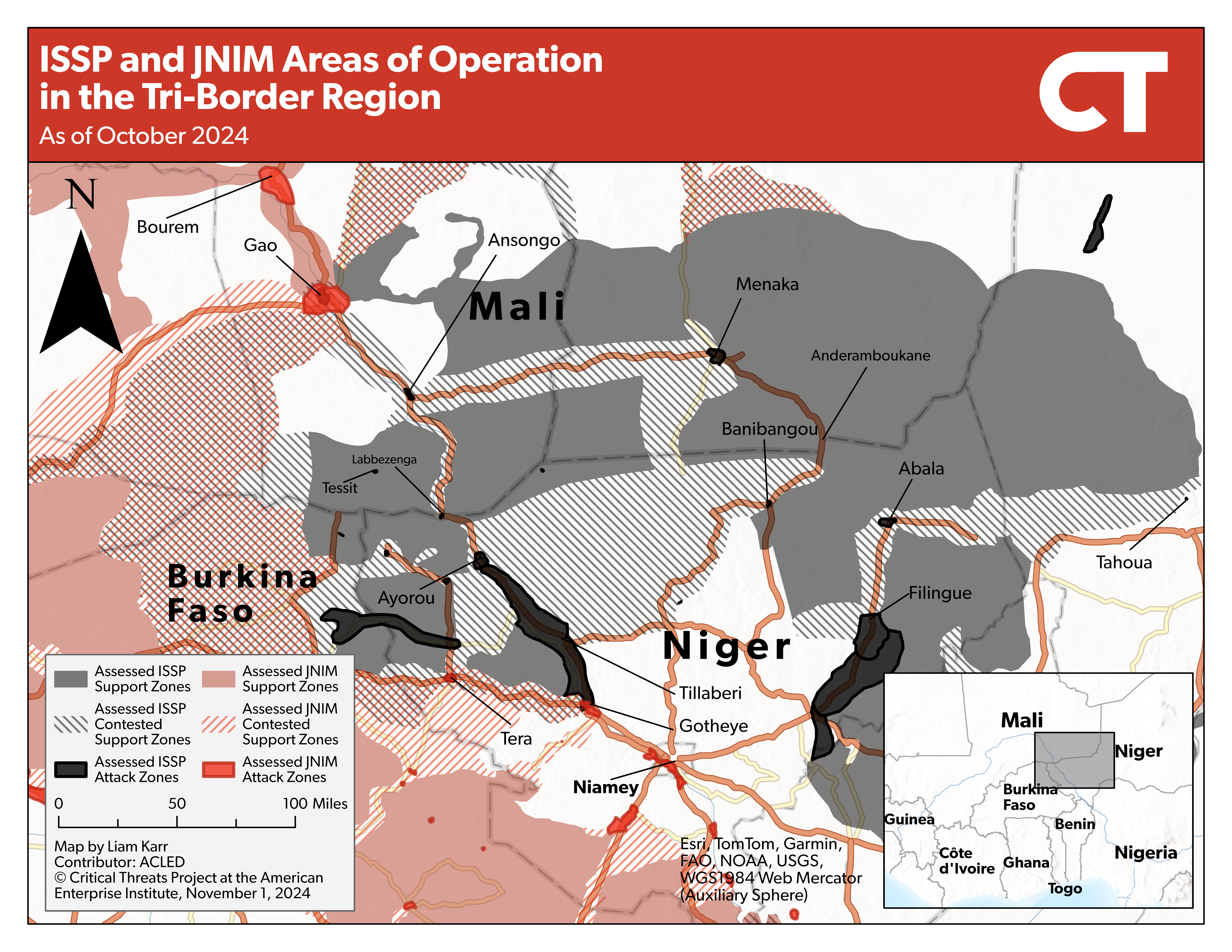

Map updated November 1, 2024

Attack Zone: An area where units conduct offensive maneuvers.

Contested Support Zone: An area where multiple groups conduct offensive and defensive maneuvers. A group may be able to conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces but has inconsistent access to local populations and key terrain.

Support Zone: An area where a group is not subject to significant enemy action and can conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces.

Control Zone: An area where a group exerts largely uncontested physical or psychological pressure to ensure that individuals or groups respond as directed. Control zones are a subset of support zones.

Methodology Note: The Critical Threats Project adapts its mapping definitions for insurgencies from US military doctrine, including US Army FM 7-100.1 Opposing Force Operations. Our maps are assessments and reflect analysts’ judgment based on current and historical open-source information on security incidents, political and governance activity, and population and geographic factors. Please contact us for more information on specific maps.

Prior Versions

Table of Contents

November 2024 Update

The latest update reflects extensive changes based on the strengthening of the regional al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates—Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) and IS Sahel Province (ISSP), respectively. There has been significant political upheaval in the central Sahel since the last update, in 2022. Burkina Faso and Niger experienced coups that installed junta governments, joining Mali’s junta, which took power in 2021. The new juntas cut ties with Western partners, leading to the withdrawal of thousands of French, UN, and US troops, whom a fraction of Russian soldiers have attempted to replace. The juntas have also adopted highly militarized counterinsurgency strategies that have failed to address underlying issues with the Western-backed approach of the last decade while simultaneously spreading indiscriminate violence and abuses that further fuel the insurgencies. These capacity and strategy blunders have contributed to the rapid growth of JNIM and ISSP capabilities, reach, and control. JNIM carried out its first attack in the Malian capital in nearly a decade and attacked the suburbs of the Nigerien capital. Meanwhile, ISSP’s growth has elevated the group’s role as a regional hub and increases the risk of the branch eventually supporting global IS activity, including financially or logistically facilitating attacks in Europe.

Western partners have shifted their focus to insulating coastal West Africa against spillover from the Sahel. The continued strengthening of Salafi-jihadi insurgents in the Sahel threatens to overwhelm this containment strategy. Furthermore, the political challenges with the authoritarian and anti-Western central Sahel juntas create challenges for the coastal countries and their Western partners by limiting coordination with these countries at the epicenter of the conflict.

Figure 1. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Figure 2. High-Casualty Salafi-Jihadi Attacks in the Sahel

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Background: The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Sahel

The Salafi-jihadi movement in the Sahel has roots in the Algerian Salafi-jihadi movement of the early 2000s, from which al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) emerged. AQIM gained influence in the Sahel throughout the 2000s, eventually infiltrating and co-opting a 2012 rebellion driven by long-running ethnic grievances in partnership with Ansar al Din, which is based in northern Mali. A French-led response rolled back AQIM and its allies’ conquest of northern Mali in 2013. Thousands of French and UN troops remained in the Sahel over the following decade in an effort to stem the resurgence of these insurgents.

Four Salafi-jihadi groups merged to create JNIM in 2017: AQIM’s Sahara Emirate, Ansar al Din, the Macina Liberation Front, and al Murabitoun. A fifth group, based in Burkina Faso, Ansar al Islam, is a de facto member of the group despite not formally being part of the merger. The group maintains a top-down hierarchy that orients its strategy and coordinates between the different subgroups. However, it also gives the subgroups significant operational freedom to best exploit their local contexts—such as appealing to local ethnic constituencies. JNIM has embedded itself in local governance structures and implemented various forms of shadow governance through local agreements across the Sahel. JNIM is most active in Mali and Burkina Faso, though it is present in Niger and expanding into the northern Gulf of Guinea states.

ISSP formed when a faction of an AQIM splinter group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2015. The Islamic State did not recognize ISSP as a formal province until March 2022. ISSP is most active in the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. ISSP and JNIM, unlike other al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates globally, did not initially fight each other. However, the two groups have engaged in phases of conflict since 2020. JNIM and French military pressure substantially weakened ISSP in 2020, but ISSP has significantly strengthened since the departure of French forces in 2022.

JNIM and to a lesser extent ISSP are gradually expanding south, toward the coastal Gulf of Guinea states. Overlapping issues—including climate change, poor governance, and communal tensions—are enabling the Salafi-jihadi movement to embed in local communities.

Regional Campaign Updates

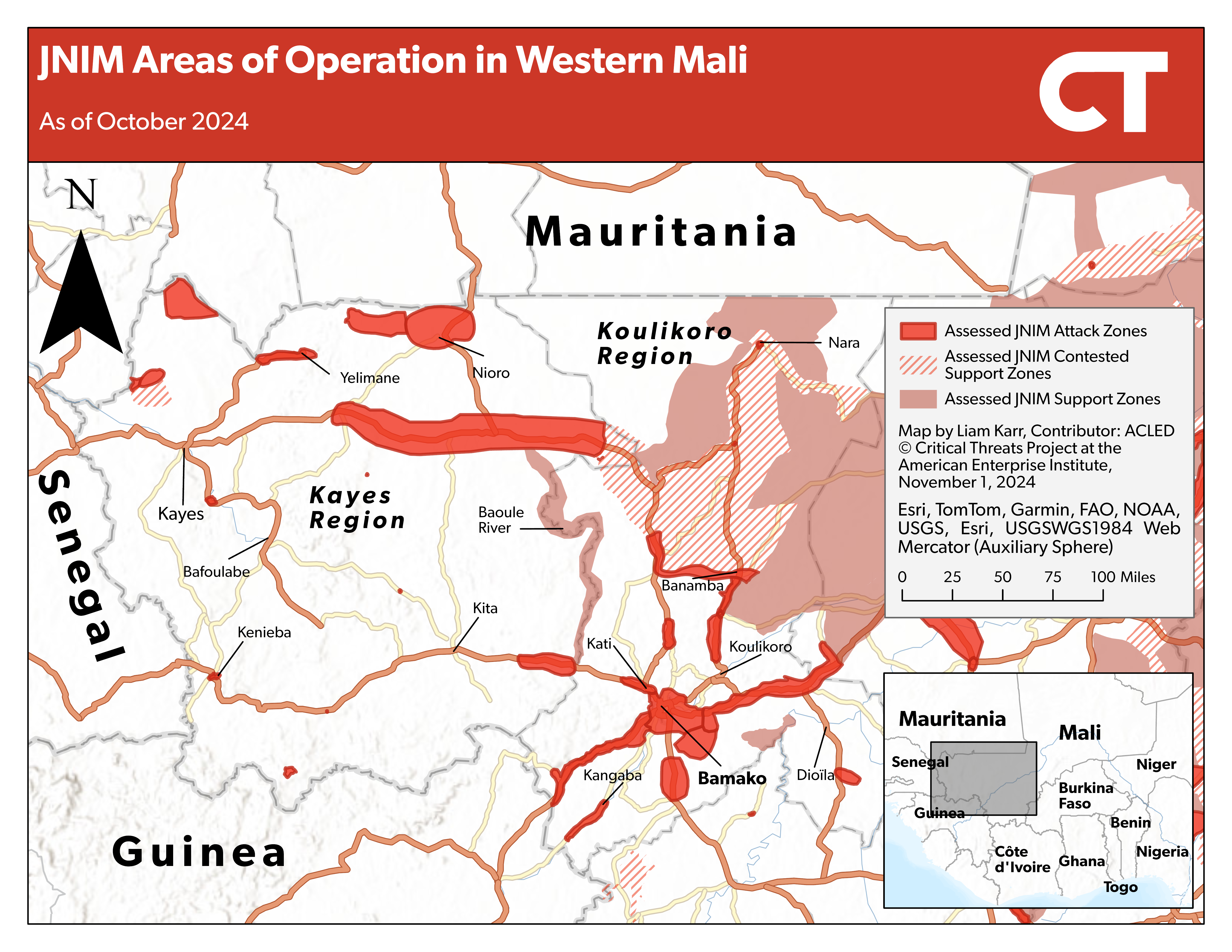

Western Mali

JNIM has increased the rate and geographic scope of its attacks in western Mali as it targets customs posts and roads connecting western Mali to Bamako. Since 2023, JNIM is on pace to average over twice as many attacks per year in the Kayes region as it conducted in 2022. The group conducted 21 attacks in 2023 and is on pace for nearly 25 attacks in 2024 after conducting only 10 attacks in 2022. JNIM has also carried out its first attacks in Kenieba cercle near the Guinean and Senegalese borders.[i]

The group has focused the majority of its attacks on border posts around the periphery of the Kayes region and roadways in eastern Kayes that connect to Bamako. JNIM has conducted at least 15 attacks within 30 miles of the Malian border in the Kayes region since the beginning of 2023.[ii] The group has likely taken advantage of the porous border security in West Africa to establish rear support zones that could help it expand further into the interior of the Kayes region.

JNIM activity near the border creates opportunities for self-sustainment. JNIM loots money and weapons from the customs posts and gendarmerie posts in some of these attacks. The group’s growing presence along the border puts it near smuggling lines involved in the illicit gold, drug, arms, and human trafficking networks that use routes connecting western Mali to coastal West Africa. JNIM has historically used its positions along illicit routes in northern Mali and Burkina Faso to generate revenue.

JNIM has also targeted roads connecting the Kayes region to Bamako, likely as part of a broader campaign to degrade Malian lines of communication around Bamako that began in early 2023. The group carried out at least 15 attacks along major roadways in eastern Kayes that lead to Bamako since the beginning of 2023. The group has attacked security forces and civilians along the RN1 road, which connects Bamako to Kayes city, and RN24, which connects Bamako to the district capital, Kita, at least six times each.[iii]

Figure 3. JNIM Areas of Operation in Western Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Southern Mali

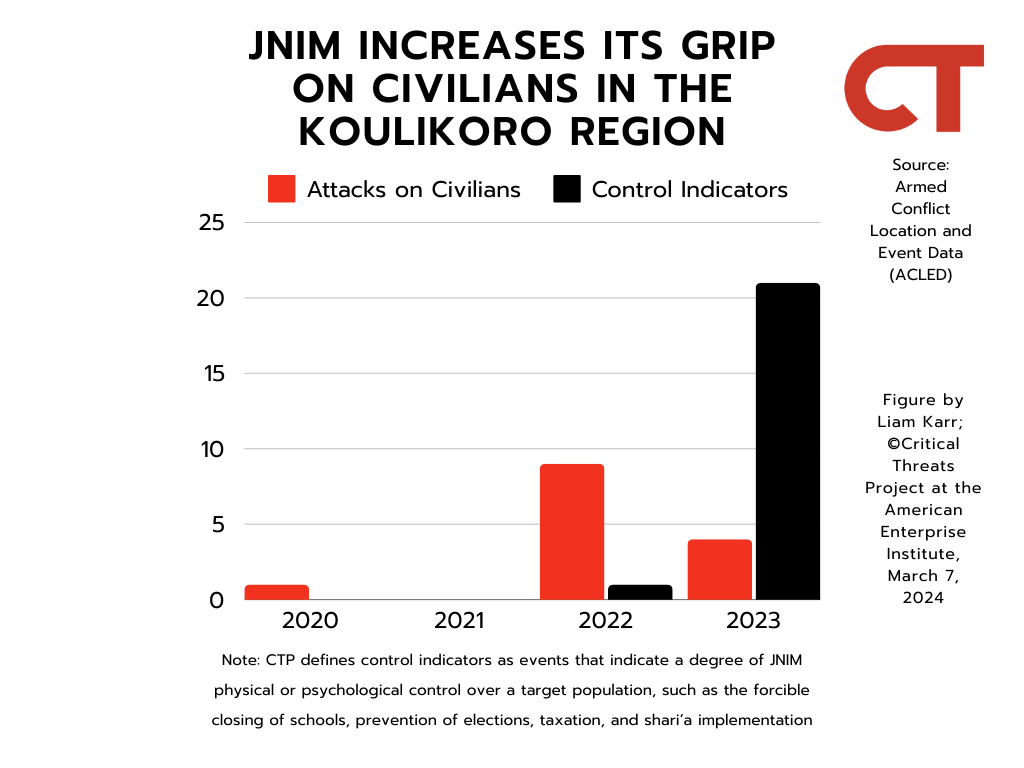

JNIM has consolidated support zones in northern Koulikoro region and western Segou region, which it uses to degrade Malian lines of communication, isolate bigger population centers, and expand southward toward Bamako. JNIM controls most rural areas of northern Koulikoro and along the Koulikoro and Segou regional border north of the Niger River. JNIM control in these areas is characterized by zakat taxation, school closures, voting prevention, and targeted abductions of local leaders with no government response. Malian counterterrorism activity in this area has also significantly declined since the beginning of 2023. Security forces initiated 22 engagements in 2022, compared with only six in 2023 and ten so far in 2024. Nearly half these security force engagements since the beginning of 2023 have been drone strikes, further illustrating the lack of state control on the ground in the area.[iv]

Figure 4. JNIM Increases Its Grip on Civilians in the Koulikoro Region

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

JNIM is using these support zones to increase pressure on nearby roadways and population centers by launching more complex and severe attacks. For example, JNIM organized two separate complex attacks involving suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs) targeting Malian military bases in northern Koulikoro in February and May 2024, respectively. JNIM also used a suicide motorcycle-borne improvised explosive device (IED) in an ambush in December 2023. The group had not conducted such sophisticated attacks in southern Mali since 2022. Security forces still regularly patrol the main roadways through the area but are subject to frequent JNIM IED and ambush attacks.[v] These attacks degrade Malian forces’ will and capacity to pressure JNIM’s rural havens and enable the group to replenish its arsenal with looted weapons, further strengthening its position in the area.

Figure 5. JNIM Areas of Operation in Southern Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Bamako Area

JNIM has significantly increased the rate and geographic spread of its attacks around Bamako since the beginning of 2023. The group also carried out its first attack in Bamako in nearly a decade in September 2024 as part of a campaign to symbolically challenge the Malian junta and build pressure around the capital. JNIM conducted 19 attacks in southwestern Koulikoro in 2023 and is on pace to carry out 17 attacks in 2024. These numbers are more than double the eight attacks the group carried out in 2022. A JNIM cell with rear basing along the Guinean border also carried out the group’s first attacks in the Kangaba region in March 2024 during a short attack spree. The severity of attacks around Bamako has not significantly changed, with fatalities remaining relatively low except for a major attack in February 2024 that killed at least 20 soldiers.[vi] CTP assessed that the group’s growing support zones in northern Koulikoro are enabling these attacks. JNIM carried out its first attack in the capital since 2015 on September 17, when it attacked a gendarmerie school and the main Malian air base in Bamako, killing more than 70 security force personnel. The group has almost exclusively targeted security forces in these attacks.

CTP has assessed since early 2023 that the increase in attacks around—and now in—Bamako is likely part of a concerted campaign to symbolically challenge the Malian junta and degrade Malian lines of communication. The choice to almost exclusively target security forces and not civilians indicates that the primary aim of the campaign is to erode the legitimacy and morale of the junta, its supporters, and the security forces by highlighting JNIM’s presence and capabilities near the capital while framing itself as a protector against the junta’s human rights abuses. JNIM has regularly highlighted the proximity of several of these attacks to Bamako and framed them as a challenge to the junta’s authority and a sign of the junta’s failure to contain the group.[vii] JNIM also took several measures that signal its September attack on Bamako was also primarily meant to undermine the junta. It once again only attacked clear military targets, published footage showing militants burning the presidential plane, and timed the attack to coincide with Mali’s Independence Day and a conference with officials from Burkina Faso and Niger.

Central Mali

JNIM expanded its preexisting support zones north of Macina city in northeastern Segou region that extend into the neighboring Timbuktu region. The group signed at least five peace agreements with the local communities and militias between August and October 2023. Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) has not recorded any clashes in the area since the agreements.[viii]

Figure 6. JNIM Areas of Operation in Central Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Burkina Faso-Mali Border

JNIM expanded its sanctuaries along the border of northwestern Burkina Faso and central Mali after short-lived counterterrorism offensive from security forces on both sides of the border in the first half of 2023. JNIM has consolidated control across a significant swath of the central Mali border with northwest Burkina Faso, specifically the rural northern portions of Burkina Faso’s Boucle du Mouhoun and Nord regions and most of Mali’s Koro region. There has been a general lack of activity across these areas outside of Burkinabe and Malian airstrikes that lacked ground components, highlighting the lack of government control in the areas. JNIM also forcibly evicted several small villages on the Burkinabe side of the border and taxed small settlements in Mali.[ix]

JNIM is using these strengthened rural support zones to isolate and pressure government-held population centers. The group has carried out fewer attacks every year since 2022, and security forces are seemingly ceding the area by conducting fewer operations and drone strikes to contest the group. JNIM embargoed Koro city in early 2024 and blocked all roads surrounding the town before voluntarily lifting the embargo after striking a deal with local leaders in February 2024. The ability to enforce such a siege underscores the group’s control around the town, and the resulting deal that ended the siege will presumably only bolster this control. ACLED has recorded one event across the Koro, Loroum, and Sourou districts on the border of Burkina Faso and Mali since the end of July, and it was a local agreement between JNIM and the local populations in a village.[x]

Figure 7. JNIM Areas of Operation Along the Mali-Burkina Faso Border

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

JNIM has taken advantage of a lack of security force resistance to strengthen its havens parts of the western Burkinabe border with southern Mali’s Sikasso region. JNIM has operated along this segment of the border with relative impunity throughout 2023 and 2024. The group closed multiple schools, regularly set up taxation checkpoints, controlled the movement of civilians, and coerced the local population with abductions on the Malian side of the border across a significant portion of Yorosso cercle. The group is less visibly active on the Burkinabe side of the border in the rural areas of northern Kenedougou province but still carries out sporadic punitive attacks against civilians. Burkinabe and Malian security forces have not responded to JNIM’s predation on civilians in either of these areas, further indicating that the area is a support zone.[xi]

JNIM is using these support zones to target roadways and degrade lines of communication between western Burkina Faso and southern Mali, which could impede regional trade. JNIM had already been sporadically attacking security forces on both the Burkinabe and Malian segments of the N9 road, which connects Bamako and Ouagadougou via Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, and Koutiala, Mali. The support zones may be bolstering this attack campaign and enabling JNIM to conduct more regular and more severe attacks on the N9. The group has carried out 10 attacks so far in 2024, surpassing its yearly total of nine attacks in 2022 and 2023. Six of its attacks in 2024 have involved IEDs, including a complex ambush in May, compared with just three such attacks in 2022 and 2023 combined. JNIM carried out its first attacks along the N8 road, which connects Bamako and Ouagadougou via Bobo Dioulasso and Sikasso, Mali, in 2023.[xii]

The N8 and N9 roads are particularly critical because they are the main two transit corridors between Bamako and Ouagadougou. These transit corridors facilitate trade between Burkina Faso and Mali, and Mali and littoral countries such as Ghana and Togo that rely on Burkina Faso to reach Mali. This threat is especially acute given the Alliance of Sahel States’s plans to leave the Economic Community of West African States, which would eliminate free trade provisions with remaining member states. Burkina Faso and Mali have already begun negotiating bilateral trade deals with Togo to mitigate this possibility, but a lack of control over these transit corridors would complicate that effort.

Northern Mali

Malian forces and their Russian auxiliaries launched a successful offensive to take control of separatist Tuareg rebel–held towns in northern Mali during the second half of 2023. However, they have failed to degrade JNIM’s remote support zones in northern Mali. Malian and Russian forces began fighting separatist Tuareg rebels for control of vacated UN bases as UN forces withdrew from Mali in the second half of 2023. The junta launched an offensive on the Kidal region in the fourth quarter of 2023, which had been a historical rebel and JNIM stronghold for more than a decade. Malian and Russian forces took control of Kidal city and smaller bases in Aguelhok and Tessalit by the end of 2023.

JNIM had support zones in this area and was previously able to maintain a lower profile due to its significant ties to the Tuareg rebels that controlled the area. The factions’ leaders have relationships dating back to at least the 1990s.[xiii] JNIM subgroup Ansar al Din initially fought alongside the Tuareg separatist rebels during the 2012 Tuareg rebellion. However, the Salafi-jihadi militants sidelined the more secularist rebels and expanded their offensive into central Mali, which prompted the French military intervention in 2013 and helped formally split the separatist rebels from the al Qaeda–linked insurgents with a 2015 peace agreement. The groups have kept in contact in subsequent years after Ansar al Din became part of JNIM in 2017, made informal ceasefire agreements in their shared support areas, maintained significant areas of operation and membership overlap, and operationally coordinated against ISSP since 2021.

The increase in security force presence in northern Mali has contributed to an increase in the rate and severity of JNIM activity in response. JNIM more than quadrupled its monthly rate of attacks in northern Mali from July through November 2023 during the Malian-Russian offensive on Kidal compared with the first half of 2023.[xiv] The group also conducted at least three attacks involving suicide VBIEDs against Malian forces in northern Mali from September through November 2023 after not conducting any such attacks against security forces in the area nearly five years. The group similarly conducted nearly twice as many attacks against security forces during a Malian-Russian offensive in Kidal in June and July 2024 as it did in the entirety of the first five months of 2024.[xv]

Figure 8. JNIM Areas of Operation in Northern Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Malian and Russian forces have degraded JNIM’s support zones around major population centers like Kidal but have done so by indiscriminately attacking suspected civilian collaborators. ACLED recorded that over 90 percent of engagements involving Malian forces and their Russian auxiliaries in northern Mali has involved targeting civilians. These operations have seemingly degraded JNIM’s support zones and ability to attack major population centers. JNIM has carried out only three attacks targeting Kidal city in 2024 after conducting 15 in the last quarter of 2023.[xvi] The group has also been less active around other base towns, such as Aguelhok and Anefis.

However, security forces have so far been unable to degrade JNIM’s support zones and capabilities in more remote areas of the Kidal region despite voluntarily prioritizing other areas of Mali. JNIM carried out a massive ambush in late July that halted a monthslong operation to clear insurgent support zones in remote areas northeast of Kidal city that began in June. The attack involved at least two suicide VBIEDs and destroyed a Malian-Russian convoy after the Tuareg rebels had forced the convoy to retreat from the town of Tinzaouten, near the Algerian border, in late July. The attack killed over 100 Malian and Russian soldiers. The group was able to muster the resources for this attack despite the UN reporting that JNIM had willingly prioritized central Mali over northern Mali in 2024. CTP assessed after the attack that security forces face several challenges to degrading JNIM’s support zones in this area, including long-term capacity issues that make them over-reliant on air support and the porous Algerian border.

Tri-Border (Liptako-Gourma) Area

ISSP established dominance over JNIM along the Malian-Nigerien border, enabling ISSP to consolidate control over areas around the regional capitals Gao and Menaka and focus on expanding these zones across the border into Niger. ISSP launched an offensive against civilians suspected to be hostile to the group and JNIM in northeastern Mali in the second half of 2022 following the withdrawal of French forces from Mali. The fighting killed over 700 IS and JNIM fighters by the time IS had largely cleared JNIM from the Menaka region and areas south of Gao city by the end of July 2023. The UN reported that this amounted to ISSP doubling the area under its control between 2022 and the first half of 2023.

ISSP began increasing political and governance efforts in these areas during the spring of 2023, implementing various economic, health, infrastructure, judicial, and security initiatives. These policies included regulating water tower usage, reopening weekly markets, financing health services, and providing security patrols around towns and for traders traveling to nearby markets. ISSP also carried out shari’a punishments at least five times in the Gao and Menaka regions between June and November 2023.[xvii] The group has also besieged Mali’s easternmost regional capital, Menaka town, causing a humanitarian crisis as the town grapples with inflation and refugees that fled ISSP’s violence.

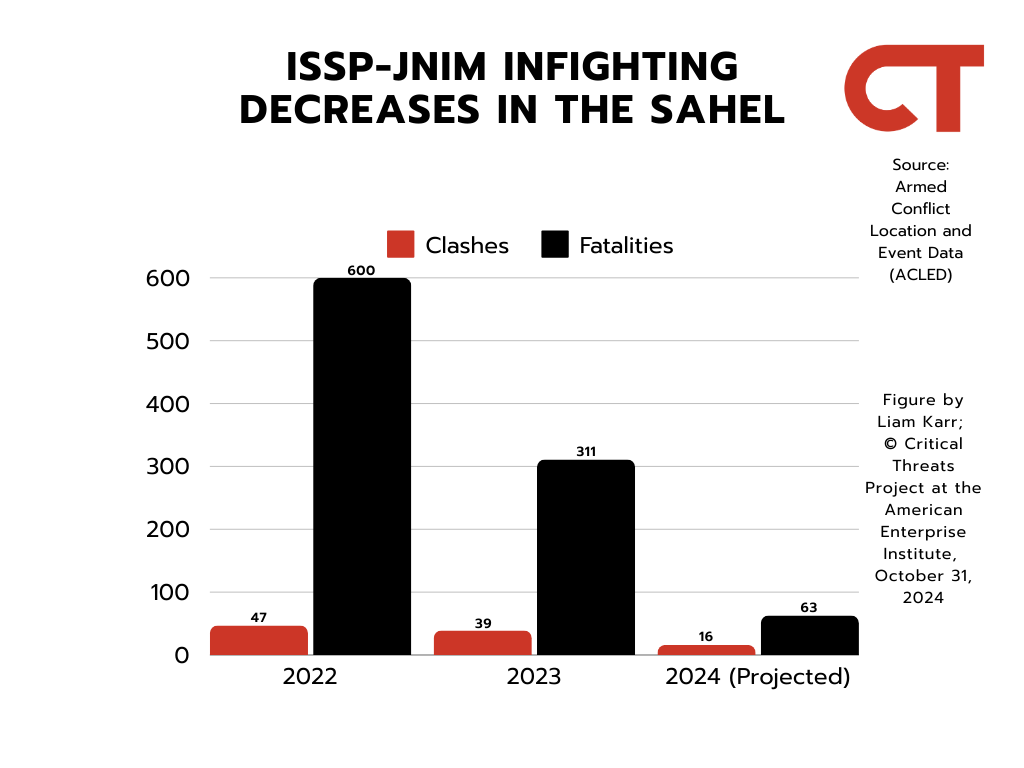

ISSP and JNIM have continued to clash in the tri-border area of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, but their battles have decreased in frequency and severity since 2022. The overall number of IS and JNIM fatalities resulting from fighting between the two groups halved between 2022 and 2023, from 600 to just over 300. This trend has continued through 2024, as the groups are on pace to end the year with less than 100 fatalities from infighting. Attacks have also become less frequent, decreasing from 47 in 2022, to 39 in 2023, and only 14 so far in 2024. Attacks are also shifting further south and west due to ISSP’s gains in Menaka and Ansongo. The two groups have only clashed in Ansongo cercle and the Menaka region in two small clashes since July 2023.[xviii]

Figure 9. ISSP and JNIM Areas of Operation in the Tri-Border Region

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Figure 10. ISSP-JNIM Infighting Decreases in the Sahel

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

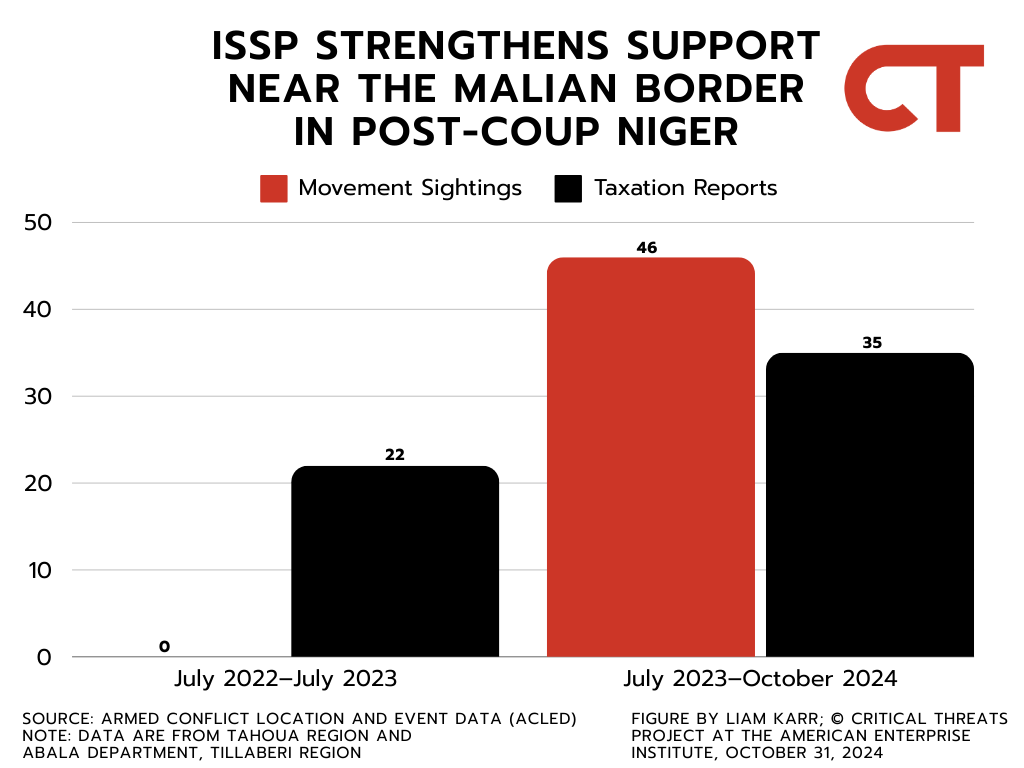

Northwestern Niger

ISSP is consolidating control over a growing hub in the northeastern Tillaberi region that extends into the neighboring Tahoua region, across the border into Mali, and around Niamey’s eastern flank. ISSP is consolidating control over a large area covering part of the Tahoua region and extending west into Tillaberi’s Abala department. ACLED recorded 45 instances of ISSP movement in this area in the first year of junta rule after recording no such activity in the previous year. CTP cannot verify whether a methodological or source change in the ACLED database contributed to this change. However, ACLED recorded other insurgent movements in the year before the coup, indicating this is a genuine development.[xix]

Increased reports of zakat extortion and religious regulation since the July 2023 coup support the assessment that ISSP is consolidating control in these areas. ISSP was already extorting civilians throughout Tahoua in the year before the coup, but this activity increased by 30 percent according to ACLED. ISSP began taxing civilians in Abala more extensively under the junta, as the reported instances jumped from two in the year before the coup to nine in the first year of junta rule. ISSP also dictated local Eid celebrations in northern Abala in April 2024 and claimed to carry out shari’a punishments near the Mali-Niger border.[xx]

Figure 11. ISSP Strengthens Support near the Malian Border in Post-Coup Niger

Note: Data are from Tahoua region and Abala department, Tillaberi region.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

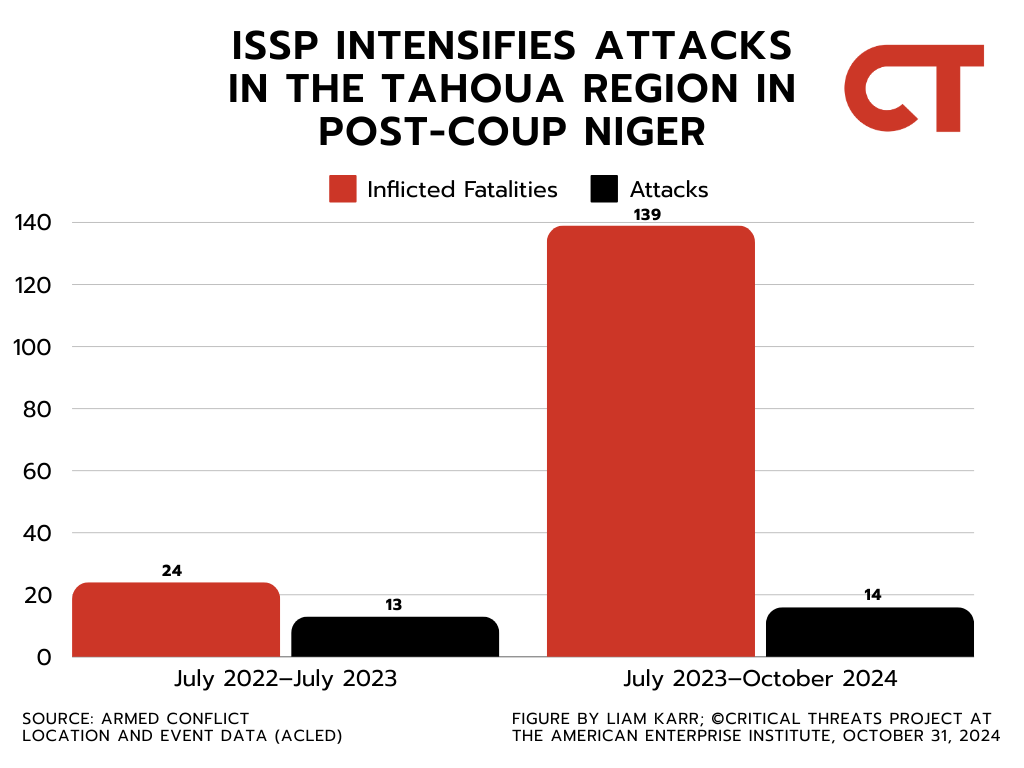

ISSP has also carried out increasingly lethal attacks against the Nigerien military in Tahoua, likely to keep security forces out of these support zones. Nigerien security force fatalities in Tahoua more than tripled under the first year of junta rule.[xxi] This spike is mostly due to a massive ISSP ambush in October 2023, which local sources claimed killed over 100 soldiers and involved sophisticated weaponry such as suicide VBIEDs. All these factors indicate that the area is part of or near an ISSP support zone, which would be required to stage such an attack.

Security forces have decreased their rate of activity in Tahoua, likely due to a lack of capacity and will. Nigerien security forces in Tahoua reportedly refused to leave their bases after the deadly October ambush, presumably contributing to the decrease in activity in the region. The 1,500 French troops that withdrew from Niger were also focused on supporting Nigerien soldiers to degrade ISSP along the Malian border. The 1,100 US personnel in Niger before the coup conducted intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support for these operations. The Nigerien junta has increased its activity in other areas of Niger along the Burkinabe border, indicating it is prioritizing those areas and cannot compensate for the capacity cuts following the French and US withdrawals.[xxii]

Figure 12. ISSP Intensifies Attacks in the Tahoua Region in Post-Coup Niger

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Southwestern Niger

ISSP is increasingly extending its support zone in northwestern Niger farther south down Niamey’s eastern flank into the Dosso region. ISSP carried out its first-ever attacks on the road connecting the department capitals Balleyara and Filingue in the past year.[xxiii] ISSP already had a quiet presence near the borders with Tillaberi, Tahoua, and northeastern Dosso before the coup and carried out occasional zakat extortion. The reported instances of zakat extortion have decreased since the coup, but these reports moved farther west near Loga, which is closer to Niamey.[xxiv] Meanwhile, the group has enjoyed much greater freedom of movement throughout Dosso and faced little resistance in the areas where it had been collecting zakat before. These trends indicate that it has consolidated a degree of control in the area, which would contribute to suppressed reports coming out of the area.

Figure 13. ISSP and JNIM Areas of Operation in Southwestern Niger

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

JNIM is making inroads into southwestern Niger along two axes and encroaching on Niamey despite strong government efforts to degrade its havens along the Burkinabe border. JNIM launched an offensive against security forces and local militias in Gotheye department between Gotheye city and the Samira mine near the Burkinabe border in early 2024. The campaign has subsided since February, but JNIM has regularly attacked Nigerien security forces attempting to reach Samira since April.[xxv] This activity pattern indicates that JNIM has established some control, degraded local militias, and is now trying to keep security forces from reentering the area.

This offensive contributed to an increase in both the number of attacks and fatalities in the area in the post-junta period. JNIM significantly increased IED attacks targeting security forces traveling the road in the area, attacked local communal militias, and expanded attacks closer to Gotheye city than it had previously. One of the militia clashes in February killed at least 34 militiamen, which is more than six times the total number of casualties across Gotheye in the year before the coup.[xxvi]

JNIM is also heavily contesting the Ouro Gueladjo area between the department capitals of Torodi and Say. JNIM was already present in the area before the coup and had evicted several nearby villages in early July 2023. JNIM has since significantly increased IED and ambush attacks on security forces in the vicinity of Ouro Gueladjo.[xxvii] These attacks signal a JNIM effort to isolate the security forces in the town and protect the support zones established in July 2023. The continued pace of JNIM attacks further indicates that the group has been successful and that security forces have not degraded its capabilities in the area.

CTP assessed in April 2024 that JNIM aims to consolidate support zones in this area to amplify pressure surrounding Niamey. JNIM’s attack campaigns near Samira and Ouro Gueladjo are near key roads leading to the capital. JNIM has already used its havens around Ouro Gueladjo and the Torodi district to attack the RN6 connecting Torodi town and Niamey. Militants can use the same havens they use to attack Ouro Gueladjo to facilitate attacks on the RN27, which connects Say and Niamey. JNIM support zones in the Gotheye department would also enable the group to conduct attacks along the RN1 or RN4 highways that run along the Niger River and connect several department capitals in northwestern Niger to Niamey.

JNIM activity around Niamey mirrors the group’s pattern of activity around the Malian capital in the year before its September attack on Bamako. JNIM attacked a security post in the Niamey suburbs in October and had already carried out three attacks within five miles of the Niamey administrative limits in 2024.[xxviii] JNIM had waged a similar attack campaign around Bamako since early 2023 but had not prioritized attacking the capital until September 2024. The group had also similarly consolidated support zones roughly 75 to 200 miles north of the Malian capital that CTP assessed JNIM used to support these attacks and eventually the cell in Bamako.

Eastern Burkina Faso

JNIM has expanded its rural support zones across eastern Burkina Faso, enabling it to besiege isolated population centers and carry out increasingly deadly attacks against resisting security forces and civilians. Burkinabe forces have almost entirely relied on drone strikes to disrupt JNIM fighters otherwise moving freely through forested or rural areas of eastern Burkina Faso, including roads leading into the park complexes on the border with Benin and Togo. There has been a lack of recorded activity across rural portions of the Est region north of Fada N’Gourma and along the border of the Sahel region despite JNIM remaining active in areas surrounding these likely support zones. JNIM also forcibly evicted civilians, extorted taxes, and carried out coercive attacks against civilians with little to no contestation from Burkinabe forces south of Noumounou between the N19 road and the Nigerien border.[xxix]

JNIM is using these support zones to besiege government-held population centers. The group has regularly used these siege tactics across Burkina Faso and Mali to isolate areas hosting or cooperating with state security forces and coerce them into noncooperation with the government. The sieges have caused mass inflation, the collapse of health services, deteriorating infrastructure, and food insecurity.

Figure 14. JNIM Areas of Operation in Eastern Burkina Faso

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

JNIM activity in the area has become increasingly deadly as it targets large Burkinabe convoys trying to resupply and reinforce these areas and overwhelms weakened and isolated towns. JNIM has initiated exponentially fewer engagements in southeastern Burkina Faso since 2022. However, fatalities have exponentially increased, indicating that JNIM attacks are becoming larger and deadlier because of this campaign. JNIM-initiated engagements resulted in the deaths of 424 civilians, insurgents, and soldiers in 2022. This number nearly tripled to 1,288 in 2023 and is on track to reach nearly 1,800 in 2024.[xxx] This is reflected in an exponentially growing number of high-casualty events across the area. Local communities had previously engaged JNIM in dialogue to lift the sieges in exchange for certain concessions, but junta leader Ibrahim Traoré has rejected this approach in favor of mobilizing civilians against the insurgents.[xxxi] The result has been greater violence against civilians perceived to be resisting the insurgents.

Figures 15-16. JNIM Intensifies Attacks in Southeastern Burkina Faso

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

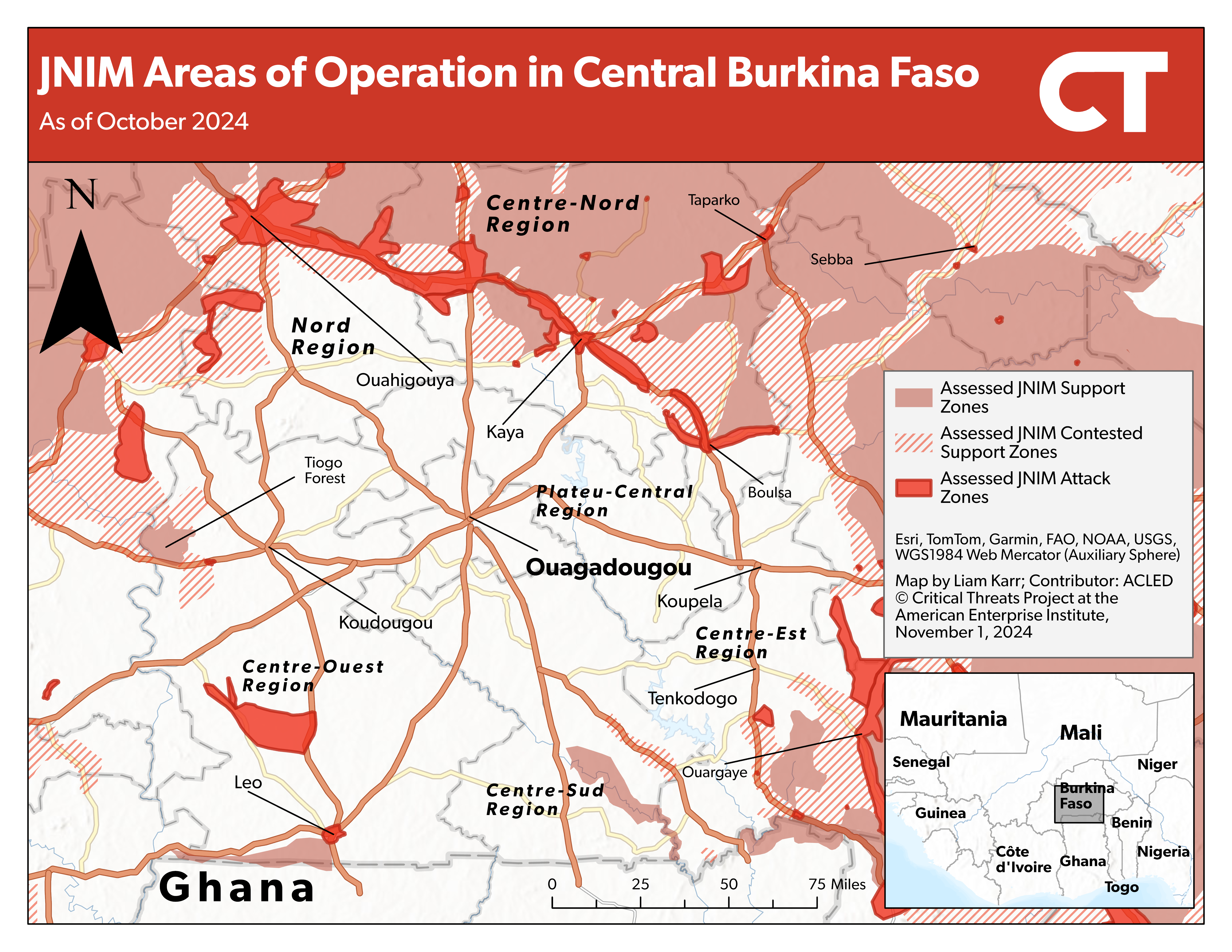

Central Burkina Faso

Burkinabe forces and their civilian auxiliaries degraded JNIM’s efforts to establish a foothold west of Koudougou, the Centre-Ouest regional capital that is 50 miles west of Ouagadougou. Security forces significantly increased their operations in 2023 to contest increased JNIM activity in the Centre-Ouest region in 2022 into the first half of 2023. JNIM conducted 17 attacks across the Centre-Ouest region in 2022 and 20 attacks in the first half of 2023. Many of the attacks in 2022 targeted high-value targets, such as gendarmerie bases and important local officials. The group also began attacking communications infrastructure and closing schools in late 2022. This pattern indicates an effort to erode the local fabric and create space for JNIM to insert itself as the de facto authority in the area.

Security forces and the local population responded by launching several counterinsurgent operations between March and May. Burkinabe forces conducted 12 operations during this period, including a series of engagements that were part of “Operation Npoupo” in late May. Soldiers and civilian auxiliaries claimed to have killed nine militants and destroyed five bases across seven localities in Operation Npoupo. Burkinabe forces have since kept up sporadic pressure on the group’s remaining havens around the Tiogo forest, contributing to JNIM only carrying out 15 attacks since the end of May 2023.[xxxii]

Figure 17. JNIM Areas of Operation in Central Burkina Faso

Source: Liam Karr

JNIM’s growing strength in rural northern Burkina Faso has enabled it to employ its siege strategy to increase pressure around the Centre-Nord regional capital Kaya, which is the lynchpin for Burkinabe security forces that shields Ouagadougou and lies roughly 60 miles north of the capital. Security forces have almost exclusively relied on drone strikes and long-range artillery to contest JNIM in rural areas of the Centre-Nord region north of the N15 road that runs east–west across the region.[xxxiii] JNIM is also besieging several towns north of the N15. Towns like Barsalogho, Bourzanga, and Pensa face regular attacks by JNIM, and security forces stationed in these towns are frequently ambushed when they attempt to travel outside their towns.[xxxiv] This has included massive JNIM attacks that highlight its strength in the surrounding rural areas. JNIM attacked Barsalogho on August 24 and massacred civilians that security forces had mobilized to dig trenches around the town. Most sources said the attack killed between 200 and 400 civilians.

CTP assessed in July that JNIM likely aims to consolidate uncontested control over these areas, which would set conditions for the group to begin a campaign to neutralize Burkinabe security forces stationed in Kaya. Kaya is a strategic point in north-central Burkina Faso that houses the main military base in the region between JNIM-contested territory and the capital, Ouagadougou. JNIM has already increased the intensity of its attacks along the N3 road northeast of Kaya in May and June.[xxxv] JNIM consolidating control north of the N15 will enable the group to similarly degrade government activity along the N15 road. The increasingly severe activity around Kaya follows JNIM’s broader pattern of besieging towns—including provincial capitals—around Burkina Faso.

[i] Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[ii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[iii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[iv] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[v] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[vi] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[vii] SITE Intelligence Group, “JNIM Claims Simultaneous Attacks on Malian Gendarme Posts in Koulikoro,” January 10, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; SITE Intelligence Group, “In New Year's ‘Gift’ to Malian Government, JNIM Claims Two Simultaneous Attacks Near Capital City,” January 4, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com

[viii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[ix] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[x] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xi] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xiii] Alexander Thurston, Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local Politics and Rebel Groups (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 107, 110, 114, 118, and 130.

[xiv] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xv] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xvi] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xvii] Author’s database of significant activity (SIGACT). Available by request. SITE Intelligence Group, “Spotlighting ‘Sahel Province’ in an-Naba 405, IS Reports Expansion of Advocacy Efforts and Execution of German Forces’ Office Employee in Mali,” August 25, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com

[xviii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xix] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xx] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxi] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxiii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxiv] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxv] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxvi] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxvii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxviii] SITE Intelligence Group, “JNIM Claims Attack Outside Nigerien Capital, Strikes on VDP Militia in Burkina Faso and FAMA and PMC Wagner Group in Mali,” January 15, 2024, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED), available at www.acleddata.com

[xxix] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxx] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxxi] https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/2021/12/16/can-local-dialogues-jihadists-stem-violence-burkina-faso; https://acleddata.com/2024/03/26/actor-profile-volunteers-for-the-defense-of-the-homeland-vdp; https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/burkina-faso/313-armer-les-civils-au-prix-de-la-cohesion-sociale; https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230413-general-mobilisation-declared-in-burkina-faso-after-series-of-jihadist-attacks

[xxxii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxxiii] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxxiv] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.

[xxxv] ACLED database, available at www.acleddata.com.