{{currentView.title}}

May 12, 2023

Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update, May 10, 2023

To receive the Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update via email, please subscribe here. Follow CTP on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook.

Contributor: Will Harvey

Data Cutoff: May 10, 2023, at 10 a.m.

Key Takeaways:

Iraq and Syria. ISIS is expanding its support zones in the Middle Euphrates River Valley (MERV) despite falling attack claims. The US mission in Syria claimed that Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) clearing operations helped to cause falling attack claims, but the SDF often fails to hold terrain following operations, which allows ISIS presence to return. ISIS will use these areas to plot complex attacks against detention facilities. US-led targeted raids against planners for these attacks are insufficient because ISIS is a decentralized, networked organization that does not have a single point of failure. It can reconstitute planning cells.

Somalia. The Somali Federal Government (SFG) has improved security around Mogadishu since February. Al Shabaab has not conducted a mass casualty attack in the Somali capital since late February, after conducting three such attacks between November 2022 and February 2023. The SFG’s central Somalia offensive has likely degraded al Shabaab’s support zones and lines of communication north of Mogadishu that they previously used to support attacks in the city. The SFG has also deployed new Ugandan-trained soldiers in the capital that are degrading al Shabaab’s access to sensitive parts of Mogadishu. Al Shabaab is also likely giving priority to attacking Somali forces farther south to preempt the SFG’s planned offensive in southern Somalia, which is contributing to the decrease in attacks in the capital.

Sahel. The Islamic State affiliate in the Sahel is on course to eclipse its strength at its prior peak in 2020. The group has restrengthened across multiple fronts in the Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger tri-border area since the French drawdown in northern Mali in 2022 and is a threat to US personnel and interests in West Africa. Al Qaeda–linked militants have also increased attacks targeting civilians farther south in the northern regions of Benin and Togo. The Beninese and Togolese governments have responded with increased security measures, which are necessary to degrade the Salafi-jihadi insurgents’ long-standing support zones in the area but risk exacerbating the grievances that drive local support for the insurgency.

Pakistan. Read CTP and ISW’s latest Salafi-Jihadi Movement Update Special Edition on the Protests in Pakistan here.

Assessments:

Iraq and Syria.

The first quarter 2023 inspector general report for the US mission in Syria does not accurately portray the threat ISIS presents in Syria.[1] The report focused heavily on the US-backed SDF-controlled areas of Syria and did not address central Syria’s ISIS presence.[2] Combined Joint Task Force–Operation Inherent Resolve’s (CJTF-OIR) mission in Syria is to “enable the enduring defeat of ISIS,” which must take into account both regime- and SDF-controlled areas.[3] ISIS kinetic activity in northeastern Syria decreased during the first quarter of 2023, but continued ISIS control indicators—such as intimidating locals—suggest that the group is not weakened in northeastern Syria.[4]

ISIS’s campaigns in regime-controlled and SDF-controlled areas are mutually reinforcing, and focusing on one area without addressing ISIS’s presence in other areas will not defeat ISIS. ISIS operations along the Euphrates River seek to create support zones and freedom of movement that permit the group to move forces and assets to and from the central Syrian desert to evade counterterrorism pressure or increase attacks. ISIS also controls territory in the central Syrian desert, where it can train new forces, hide leaders, and rest forces between operations.[5] ISIS moves new recruits from internally displaced persons camps into the desert, and it also moved several leaders into the desert after the 2022 Al Sina’a prison break.[6]

Counter-ISIS operations did not lead to a “steady decline” in ISIS activity in the MERV.[7] CJTF-OIR reported in the first quarter 2023 report that counter-ISIS operations led to a “steady decline” in ISIS activity in the MERV, citing a major SDF-led clearing operation in Raqqa in January 2023, and targeted raids against ISIS planners as evidence.[8] Raqqa primarily acts as a logistics corridor that allows ISIS to move supplies through Raqqa and into the central Syrian desert.[9] ISIS attacks increased by at least a third in the central Syrian desert during the first quarter of 2023 compared to the first quarter of 2022, indicating that these SDF efforts failed to interdict ISIS supply lines.[10] The clearing operation was also counterproductive. The operation captured one ISIS leader, but local media reported the SDF arrested local Raqqawis for protesting the SDF.[11] The SDF also released many of the arrested locals, suggesting that those detained were not ISIS supporters.[12] These efforts are counterproductive because they antagonize the population and make it more difficult for the SDF to present itself as a protector of the population against ISIS. Finally, ISIS operations decreased in the MERV as operations increased in the central Syrian desert, suggesting ISIS may have increased its prioritization of the central Syrian desert in early 2023.[13]

Figure 1. ISIS Support and Contested Support Zones in SDF-controlled Deir ez Zor

Note: CTP defines a contested support zone as an area where multiple groups conduct offensive and defensive maneuvers. A group may be able to conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces but has inconsistent access to local populations and key terrain. CTP defines a support zone as an area where a group is not subject to significant enemy action and can conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces.

Source: Brian Carter.

Targeted raids against ISIS planners are helpful but insufficient while the SDF is failing to secure the population in northeastern Syria. ISIS’s center of gravity lies in its ability to embed itself within the Sunni population.[14] No single ISIS planner or leader constitutes a “single point of failure” for the group, which is a networked, decentralized organization.[15] The SDF’s inability to secure the population allows ISIS to carve out new support zones and embed itself in the population. A local farmer in the MERV told northeastern Syria-focused media outlet NPASyria that he paid ISIS zakat after ISIS threats despite the SDF advising him not to pay.[16] Another farmer reported that ISIS no longer collects zakat through “intermediaries” but instead requests zakat publicly because “no one is able to report [ISIS] . . . for fear of retaliation.”[17] ISIS control indicators—including zakat collection, ordering women to veil, and assassinations—remained steady in the MERV in early 2023 compared to the fourth quarter of 2022, with roughly 20 reports of control activity.[18] ISIS support zones also expanded into new areas while it attempts to coerce the population into cooperating with it in others.[19]

The current United States and SDF counter-ISIS approach—reliant on presence patrols and targeted raids to eliminate key planners and leaders from the battlefield—does not secure the population and will not defeat ISIS.[20] ISIS has likely isolated many SDF elements along key roads and major towns in the MERV, which will very likely allow ISIS to deepen its ties with the MERV’s population. ISIS targets checkpoints and the outskirts of major towns to disrupt the SDF’s ability to patrol rural areas.[21] ISIS is already executing a campaign that aims to deepen its ties with the MERV’s population. Decreases in ISIS activity in certain areas in the MERV are reflective of its continued intimidation of the population. ISIS does not need to conduct attacks against populations or organizations already cooperating with the group. However, local support for ISIS is very brittle and reliant on ISIS coercion. A concerted US-backed SDF campaign to clear and hold areas to secure the population from ISIS fighters could reverse ISIS’s campaign.

Damascus. ISIS detonated a car bomb in Barzeh, Damascus city, targeting regime police on May 10.[22] The car bomb killed one police officer and wounded four others. The attack is the first ISIS attack in Damascus claimed by the group since September 2021.[23]

Figure 2. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Middle East

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

Somalia.

The SFG has improved security around Mogadishu since February. Al Shabaab has not conducted a mass casualty attack in Mogadishu since February 21, after conducting three major attacks there between November 2022 and February 2023.[24] This lull notably includes the Ramadan period, when al Shabaab has previously carried out attacks in Mogadishu and across Somalia.[25] Al Shabaab has carried out five large-scale suicide attacks in response to the SFG’s offensive in central Somalia since September 2022 that have targeted buildings or personnel related to the government offensive.[26]

The central Somalia offensive improved security in Mogadishu by degrading al Shabaab’s havens and lines of communication north of the capital. Somali forces have cleared large swaths of central Somalia since mid-2022, including al Shabaab havens along the main road and river valley in the region north of Mogadishu.[27] Al Shabaab attacks in this area north of Mogadishu decreased by 75 percent between January and May 2023 compared to the period between January and May 2022.[28] The Somali president boasted that people can travel safely between Mogadishu and the Middle Shabelle capital during a town hall on May 1, drawing attention to the improved security situation in the area.[29] The offensive has also liberated towns that were known to house al Shabaab facilities that supported attacks in Mogadishu.[30]

New Ugandan-trained Somali forces are also helping improve security by degrading al Shabaab’s access to parts of Mogadishu.[31] Al Shabaab infiltrates Mogadishu security forces and uses collaborators to gain access to sensitive areas of Mogadishu. Al Shabaab has had less time to penetrate the Ugandan-trained unit since it deployed in April, and the force’s United Arab Emirates–guaranteed salaries decrease financial incentives to cooperate with al Shabaab. However, al Shabaab has repeatedly shown the ability to infiltrate security forces, and the group could still coerce or convince some of these soldiers to collaborate over time.[32] There have also been no reports of the new forces extorting or murdering civilians since they arrived. Security force abuses were a prominent issue in the first quarter of 2023, and these abuses drive civilians to support al Shabaab.[33] The new soldiers also likely contributed to Somali security forces thwarting at least three al Shabaab bomb plots since the contingent arrived in Mogadishu, although it is unclear what role—if any—they played alongside Mogadishu’s police and intelligence units.[34]

Al Shabaab is also likely giving priority to attacking Somali forces farther south. The SFG has been planning to launch an offensive involving troops from Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya since early 2023 that will target al Shabaab’s strongholds in southern Somalia.[35] Al Shabaab increased the number of attacks in southern Somalia in February and March in response to Somali shaping operations for this offensive in late January.[36] The group attacked security forces 16 times in February and 14 times in March after only conducting 10 attacks in January.[37] Two of the February attacks were complex attacks involving suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs), which is the group’s first use of SVBIEDs against military forces in this region since 2020.[38] The timing of this al Shabaab offensive overlapped with the decrease of activity around Mogadishu in February, and it could indicate the group is diverting resources from the Mogadishu area farther south. The reintroduction of sophisticated capabilities like SVBIEDs further indicates that the group is allocating more resources to southern Somalia.

Figure 3. Al Shabaab–Related Activity in the Lower Jubba Region: January–March 2023

Source: Liam Karr.

Sahel.

The Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISGS) is on course to eclipse its strength at its prior peak in 2020. ISGS was expanding across large portions of the Burkinabe-Malian-Nigerien tri-border region and killing hundreds of security forces and civilians in 2019 and early 2020. This strengthening led to clashes with al Qaeda–linked militants in 2019, as the two groups fought for dominance and caused French counterterrorism forces to prioritize targeting ISGS in early 2020.[39] The simultaneous pressure from France and Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) caused ISGS to lose ground until it was largely confined to the immediate border regions by late 2020.[40]

ISGS has restrengthened across multiple fronts in the tri-border area since the French drawdown in northern Mali in 2022.[41] ISGS attacks in Mali and Burkina Faso since 2022 are now as deadly as they were in 2020.[42] The group is returning to areas in both Mali and Burkina Faso that JNIM had removed it from in 2019 and 2020.[43] ISGS was also likely behind an SVBIED attack in northeastern Burkina Faso that Burkinabe forces thwarted on May 3.[44] Burkinabe media said the attackers came from Niger, where ISGS has its support and staging zones, and ISGS had won a battle with JNIM just north of the attack target.[45] ISGS deploying a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) in Burkina Faso indicates its growing strength. ISGS has only used a VBIED on a few occasions and never in Burkina Faso.[46] ISGS also launched an offensive in northeastern Mali and began consolidating control over the area during this same period.[47]

Figure 4. ISGS Expands in the Tri-Border Region

Source: Liam Karr.

ISGS’s growth in the tri-border area will threaten US personnel and interests in West Africa. Greater ISGS strength in Niger will allow ISGS to reinforce its preexisting ties to IS’s West Africa Province in Nigeria.[48] Both groups have shown the capability and intent to target US personnel and will be able to pool resources to plot similar attacks in Niger more easily.[49] Niger is also the last reliable Western counterterrorism partner in the tri-border area after relationships with the Malian and Burkinabe juntas deteriorated.[50] Failures by the Western-backed Nigerien government and security forces will undermine faith and Western support and increase anti-Western sentiment that could lead to future Nigerien governments seeking alternate partners, like Mali and Burkina Faso have done with Russia.[51] Growing ISGS presence in northeastern Burkina Faso would also make it easier for the group to support its enclave in northern Benin through eastern Burkina Faso, threatening US and allied efforts to stabilize the Gulf of Guinea states.[52]

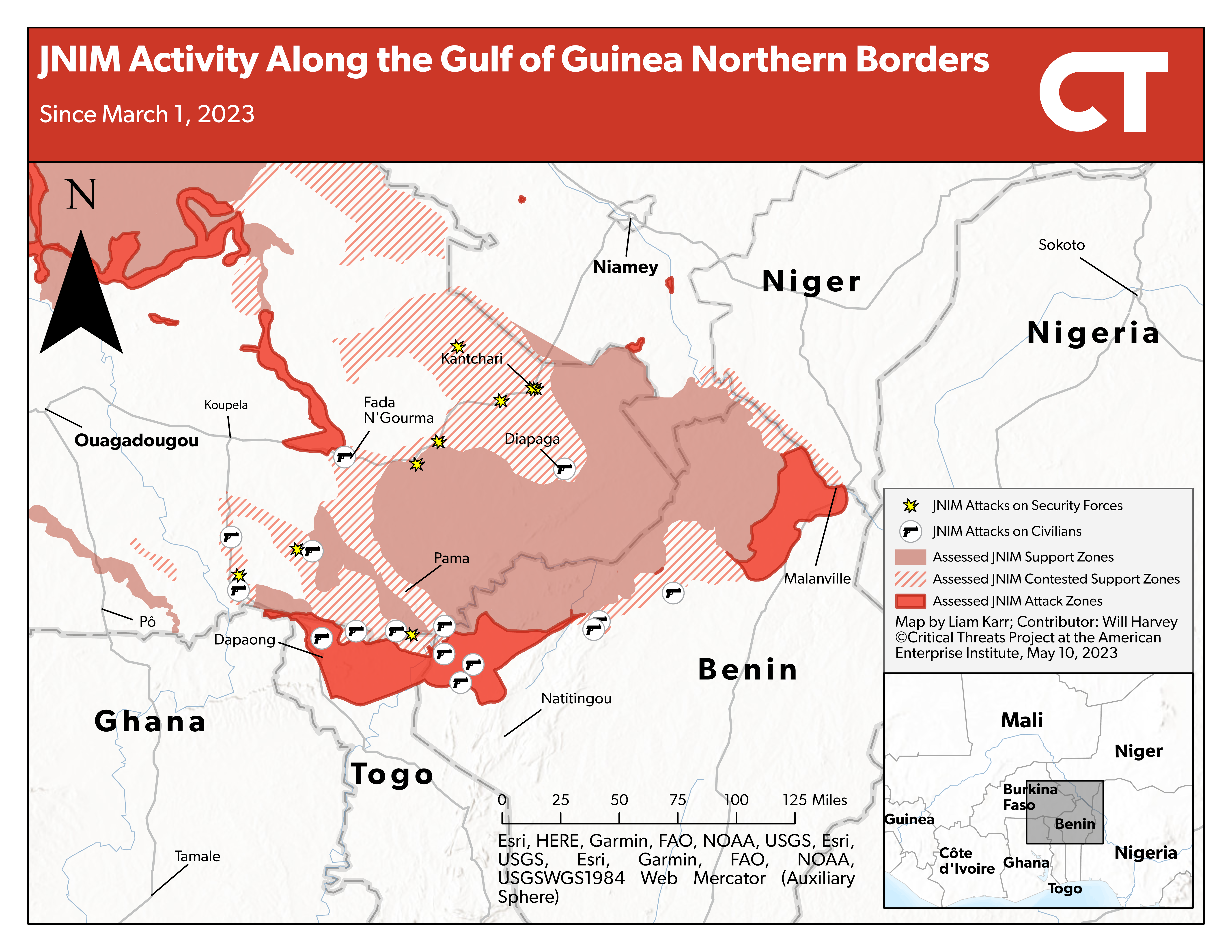

Gulf of Guinea. Al Qaeda–linked JNIM increased attacks in Benin and Togo in early May. JNIM only conducted five attacks in March and April combined after averaging five attacks per month between October 2022 and February 2023.[53] JNIM has already conducted at least five attacks targeting civilians in Benin and Togo since the beginning of May, including massacring 15 civilians in northwestern Benin on May 1.[54] These attacks continue a trend of JNIM increasingly targeting civilians in Benin and Togo since early 2023.[55] CTP continues to assess that JNIM is focusing on civilians to coerce locals and expand its support zones.[56]

Figure 5. JNIM Activity Along the Gulf of Guinea Northern Borders

Source: Liam Karr.

The Beninese and Togolese governments are taking security measures to try and contain the insurgency along their northern borders. The Beninese government announced in April that it will send 5,000 soldiers to its northern regions in May, and the Nigerien government agreed to deploy soldiers at the Beninese border in March.[57] Benin has also pursued a security agreement with Rwanda and China since late March.[58] The Togolese government reissued a declaration of emergency in its northern areas on April 6.[59]

Greater security is necessary to degrade JNIM support zones and protect communities, but risks exacerbate the grievances that drive local support for JNIM. Increasing the number of security forces in Togo and Benin is necessary to degrade JNIM’s long-standing support zones in the park complexes along Togo’s and Benin’s borders with Burkina Faso.[60] A larger troop presence could also help secure communities so the Gulf of Guinea states can safely implement already-approved programs that aim to improve social and economic resilience.[61] However, increased militarization simultaneously risks exacerbating the grievances driving the local insurgency as security forces inadvertently destroy nomadic cross-border economies and potentially increase ethnic profiling.[62] JNIM has exploited the worsening social and economic livelihoods of pastoral communities in the northern littoral states and resulting farmer-herder violence to recruit.[63]

JNIM will likely attempt to spread farther south and not settle for a buffer zone in the park complexes in northern Benin and Togo. JNIM leadership has repeatedly shown that it will give its subgroups a high degree of autonomy to address local issues and attract more fighters.[64] This relationship means that even if JNIM leadership primarily focuses on creating a buffer zone for its operations in Burkina Faso, the local Beninese and Togolese fighters will push the subgroup toward attacking their respective governments and spreading into new areas. Other JNIM subgroups exemplify this phenomenon. Al Qaeda–linked militants from central Mali created their own subgroup separate from the group’s northern Mali core in 2015.[65] This subgroup expanded to central Mali and eventually southern Mali, where it is now waging a campaign around the Malian capital as part of JNIM.[66] The Burkinabe-based subgroup has similarly expanded from northern Burkina Faso to all parts of the country and now south into the littorals.[67]

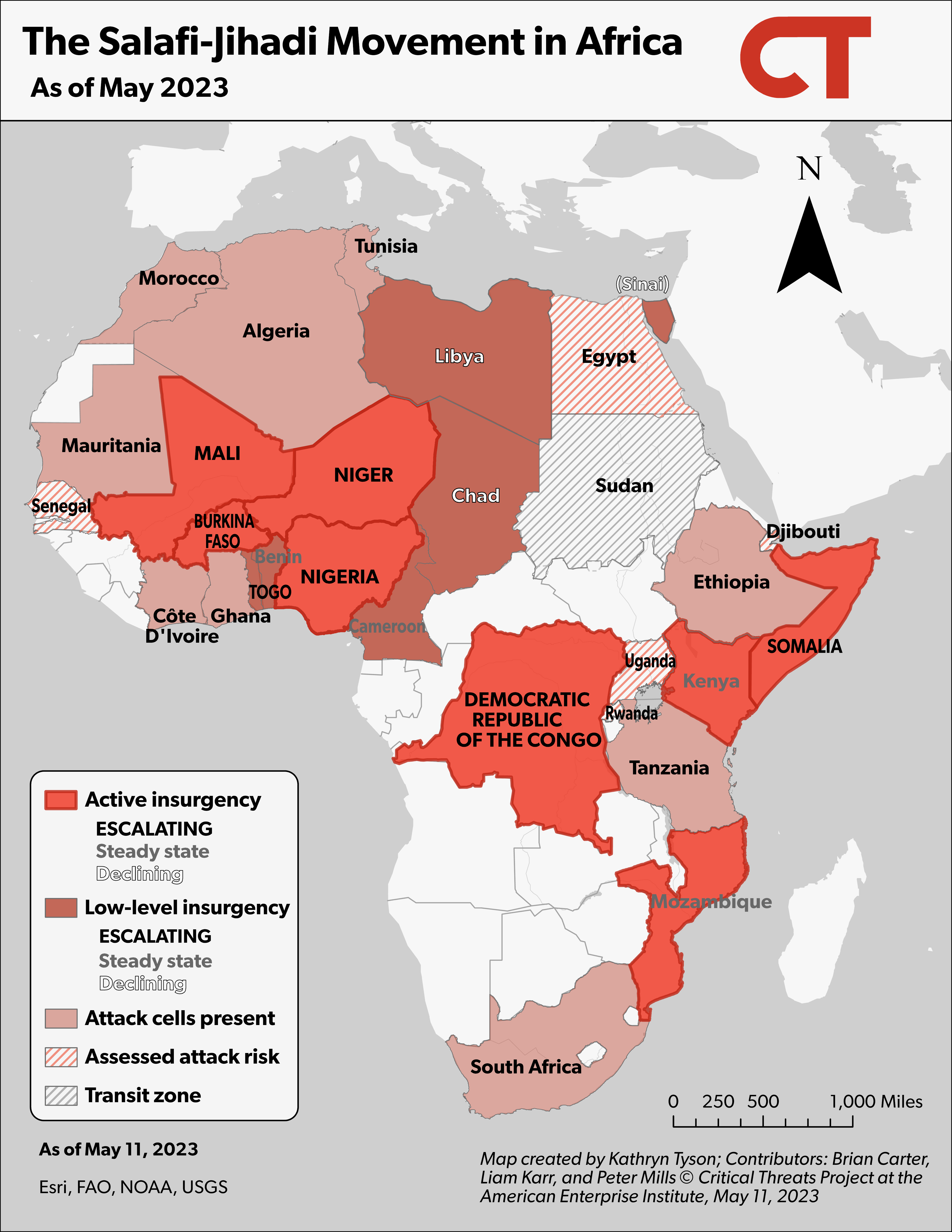

Figure 6. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

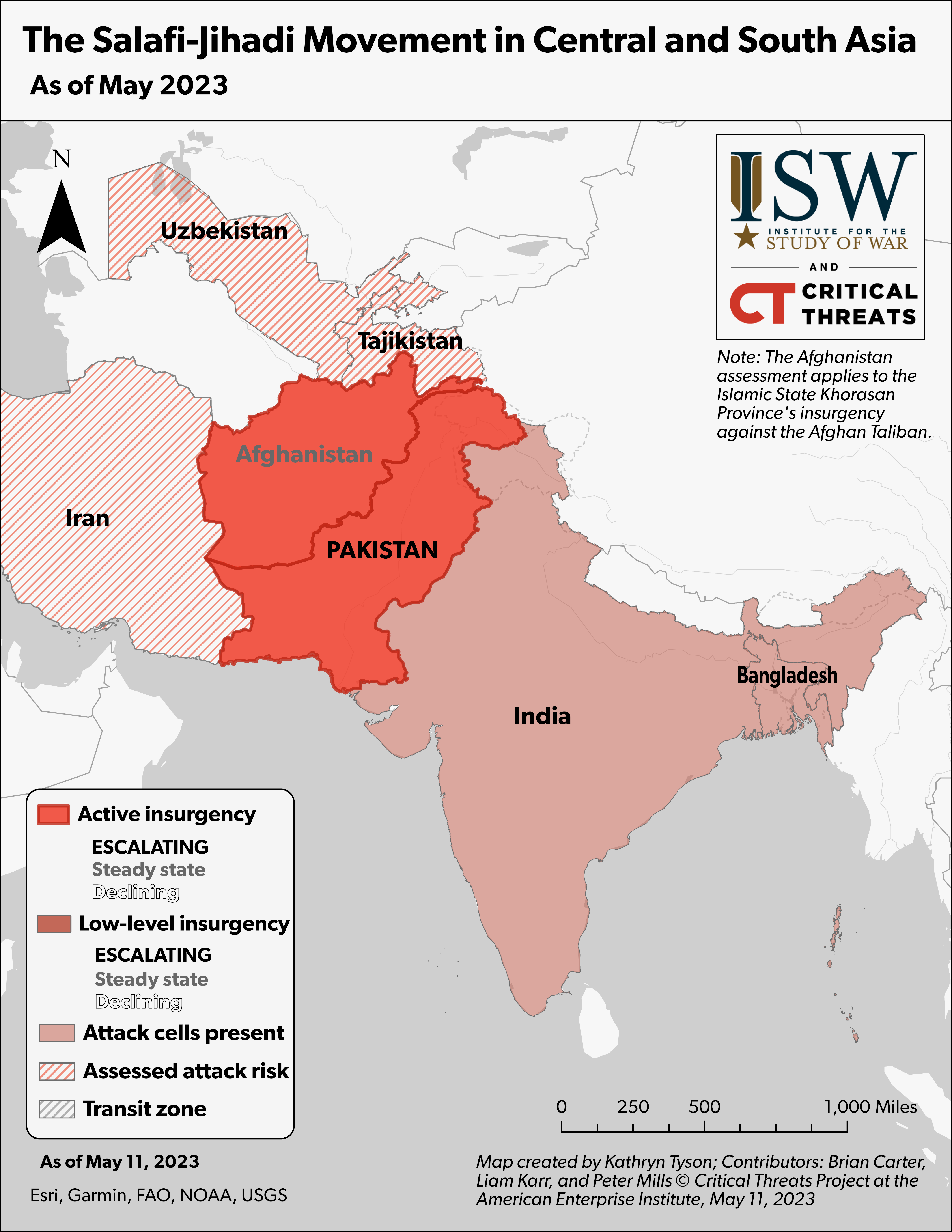

Read CTP and Institute for the Study of War’s latest Salafi-Jihadi Movement Update Special Edition on the protests in Pakistan here.

Figure 7. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in South and Central Asia

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

[1] https://www.dodig.mil/Reports/Lead-Inspector-General-Reports/Article/3380832/lead-inspector-general-for-operation-inherent-resolve-i-quarterly-report-to-the

[2] https://www.dodig.mil/Reports/Lead-Inspector-General-Reports/Article/3380832/lead-inspector-general-for-operation-inherent-resolve-i-quarterly-report-to-the

[3] https://www.inherentresolve.mil/WHO-WE-ARE

[4] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-may-4-2023

[5] https://www.mei.edu/publications/isis-beats-back-wagner-offensive-central-syria; author’s research.

[6] https://www.dodig.mil/Reports/Lead-Inspector-General-Reports/Article/3380832/lead-inspector-general-for-operation-inherent-resolve-i-quarterly-report-to-the; https://www.mei.edu/publications/closer-look-isis-attack-syrias-al-sina-prison

[7] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-27-2023

[8] https://www.dodig.mil/Reports/Lead-Inspector-General-Reports/Article/3380832/lead-inspector-general-for-operation-inherent-resolve-i-quarterly-report-to-the

[9] https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/international/290423/en-syrie-l-etat-islamique-organise-sa-survie

[10] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-27-2023

[11] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-may-4-2023

[12] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-may-4-2023

[13] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-27-2023

[14] https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Beyond-Counterterrorism.pdf?x91208

[15] See paragraph 4-95 in https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/fm3_24.pdf

[16] https://npasyria dot com/151205

[17] https://npasyria dot com/151205

[18] Author’s research.

[19] Author’s research.

[20] Author’s research.

[21] Author’s research.

[22] ISIS claim available on request.

[23] https://twitter.com/GregoryPWaters/status/1656306204782501888?s=20

[24] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/al-qaeda-global-tracker/salafi-jihadi-global-tracker-al-shabaab-besieges-hotel-near-somali-presidential-complex; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-january-25-2023

[25] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/somalias-al-shabab-islamic-extremist-group-claims-responsibility-for-bomb-blast-that-kills-at-least-6

[26] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/al-qaeda-global-tracker/salafi-jihadi-global-tracker-al-shabaab-besieges-hotel-near-somali-presidential-complex

[27] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b187-sustaining-gains-somalias-offensive-against-al-shabaab

[28] Author’s research.

[29] https://www.caasimada.net/madaxweyne-xasan-sheekh-oo-ballan-qaad-la-xiriira-doorashada-2026

[30] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/gulf-of-aden-security-review/gulf-of-aden-security-review-december-7-2022; https://allafrica.com/view/resource/main/main/id/00130649.html

[31] https://twitter.com/TheVillaSomalia/status/1637541162629120000?s=20; https://twitter.com/GaroweOnline/status/1645568986539589634?s=20

[32] https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_somalia-assesses-al-shabab-moles-infiltration-government/6173903.html

[33] https://www.caasimada.net/xasan-oo-shaaciyay-arrin-yaab-leh-oo-loogu-tagay-deeganadii-laga-saaray-al-shabaab; https://twitter.com/GaroweOnline/status/1630551741325352960?s=20; https://twitter.com/HussienM12/status/1630502900861480960?s=20; https://twitter.com/HussienM12/status/1627292681272545285?s=20; https://twitter.com/HussienM12/status/1621117167726116864?s=20

[34] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/gulf-of-aden-security-review/gulf-of-aden-security-review-april-17-2023; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/gulf-of-aden-security-review/gulf-of-aden-security-review-april-26-2023

[35] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-march-8-2023; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-12-2023

[36] Author’s research.

[37] Author’s research.

[38] SITE Intelligence Group, “UPDATE: Shabaab Claims 110+ Casualties in Suicide Bombings, Major Offensives on Multiple Bases in Southern Somalia,” February 11, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; SITE Intelligence Group, “Shabaab Claims 89 Killed in Major Offensive on Base of U.S.- and UAE-Trained and Backed Forces Outside Kismayo,” March 7, 2023, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com

[39] https://acleddata.com/2020/05/20/state-atrocities-in-the-sahel-the-impetus-for-counter-insurgency-results-is-fueling-government-attacks-on-civilians; https://ctc.westpoint.edu/the-end-of-the-sahelian-anomaly-how-the-global-conflict-between-the-islamic-state-and-al-qaida-finally-came-to-west-africa

[40] https://acleddata.com/2023/01/13/actor-profile-the-islamic-state-sahel-province; https://acleddata.com/2021/06/17/sahel-2021-communal-wars-broken-ceasefires-and-shifting-frontlines

[41] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-january-25-2023

[42] Author’s research; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/least-51-soldiers-killed-north-burkina-faso-attack-friday-army-says-2023-02-20; https://www.voanews.com/a/over-70-soldiers-killed-in-burkina-faso-extremists-say/6978914.html; https://www.voanews.com/a/malian-soldiers-killed-in-suspected-jihadi-attacks-/6696991.html; https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2020/01/islamic-state-kills-almost-100-soldiers-in-niger.php; https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/27/mali-coordinated-massacres-islamist-armed-groups; https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/23/burkina-faso-new-massacres-islamist-armed-groups; https://maliactu dot net/burkina-faso-44-civils-tues-dans-une-double-attaque-terroriste-dans-le-sahel

[43] Author’s research; https://acleddata.com/2023/01/13/actor-profile-the-islamic-state-sahel-province

[44] https://www.aib dot media/2023/05/03/burkina-un-attentat-a-la-voiture-piegee-dejouee-au-nord

[45] https://www.aib dot media/2023/05/03/burkina-un-attentat-a-la-voiture-piegee-dejouee-au-nord

[46] https://www.voanews.com/a/malian-soldiers-killed-in-suspected-jihadi-attacks-/6696991.html; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-november-13-2019

[47] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-19-2023

[48] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-19-2023

[49] https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/24/politics/niger-ambush-timeline/index.html; https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/niger/terrorism; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-islamic-state-affiliate-attempts-to-assassinate-nigerian-president; https://www.hudson.org/sahelian-or-littoral-crisis-examining-widening-nigerias-boko-haram-conflict; https://ng.usembassy.gov/security-notice-authorized-departure-status; https://ng.usembassy.gov/security-alert

[50] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-8-2023; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/burkina-faso-confirms-end-military-accord-with-france-2023-01-23; https://www.reuters.com/world/german-government-plans-deploy-troops-niger-part-eu-mission-2023-03-29

[51] https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2023/02/28/why-niger-protest-france-anti-jihadist-campaign-interviews; https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/french-convoy-faces-new-protests-after-crossing-into-niger-burkina-faso-2021-11-27; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-burkina-faso-coup-signals-deepening-governance-and-security-crisis-in-the-sahel; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-wagner-group-in-burkina-faso-will-help-the-kremlin-and-hurt-counterterrorism; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-wagner-group-deployment-to-mali-threatens-counterterrorism-efforts

[52] https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/04/implementing-global-fragility-act-what-comes-next; https://www.hudson.org/sahelian-or-littoral-crisis-examining-widening-nigerias-boko-haram-conflict

[53] Author’s research.

[54] https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20230504-b%C3%A9nin-le-pr%C3%A9sident-talon-ordonne-une-enqu%C3%AAte-apr%C3%A8s-l-attaque-contre-des-civils-%C3%A0-kaobagou; https://actucameroun dot com/2023/05/02/attaque-terroriste-au-togo-deux-personnes-enlevees-et-du-betail-emporte

[55] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-22-2023

[56] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-22-2023

[57] https://www.voaafrique.com/a/face-au-jihadisme-le-b%C3%A9nin-envisage-de-recruter-5-000-soldats-/7061192.html; https://apanews.net/2023/03/14/niger-to-send-troops-to-border-with-benin

[58] https://www.africanews.com/2023/04/16/rwanda-benin-talk-military-cooperation-over-border-security; https://chinaglobalsouth.com/analysis/does-china-sit-atop-the-drone-throne

[59] https://www.africanews.com/2023/04/07/togo-extends-state-of-security-emergency-in-north

[60] https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2022/conflict-in-the-penta-border-area/1-security-developments-in-northern-benin-in-2022; https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso-niger-benin/310-containing-militancy-west-africas-park-w

[61] https://soco dot gov.gh

[62] https://elva.org/news/atakora-analytical-report; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-22-2023

[63] https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-salafi-jihadi-groups-may-exploit-local-grievances-to-expand-in-west-africas-gulf-of-guinea

[64] https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2022/conflict-in-the-penta-border-area/3-explaining-jnim-expansion-into-benin

[65] https://africacenter.org/spotlight/confronting-central-malis-extremist-threat

[66] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-january-18-2023

[67] https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2022/conflict-in-the-penta-border-area