{{currentView.title}}

September 08, 2022

The State of al Qaeda and ISIS Around the World

Editor’s note: This is an update to “Al Qaeda & ISIS 20 Years after 9/11,” originally published in September 2021 for the Islamists.

Salafi-jihadi groups are increasingly embedded in local conflicts, even while remaining part of al Qaeda’s and the Islamic State’s global networks. These networks include a core senior leadership cadre that provides strategic guidance to regional branches and seeks to inspire and attract new recruits to their movement. The senior leadership directs resource distribution globally, helping to surge support to take advantage of opportunities as they arise in different theaters.

Salafi-jihadi groups’ growing focus on local insurgent dynamics has enabled them to build support, expand territorially, and develop new capabilities. Weak governance and unaddressed grievances have made them resilient to counterterrorism operations, including leadership attrition, and enabled their reemergence after setbacks. Globally, Salafi-jihadi groups are set to strengthen as counterterrorism pressure lessens and local conditions worsen. They have prioritized local expansion over targeting the West, their “far enemy,” because of their operational successes in regional theaters. They may be able to generate or reconstitute transnational terror attack capabilities, which US counterterrorism pressure has largely eliminated, from these local bases. Al Shabaab, for example, pursued another 9/11-style attack in 2019.

The Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan continues to reverberate through the Salafi-jihadi movement. Al Shabaab and others have cited the Taliban’s strategy as a model for their own success through jihad. Moreover, the new terrorist sanctuary in Afghanistan permitted al Qaeda to revitalize its lagging global media presence and possibly better coordinate among its affiliates. The global reduction in counterterrorism resources has also lifted pressure from many Salafi-jihadi groups, which increasingly enjoy their own regional safe havens from where they threaten to destabilize nearby states.

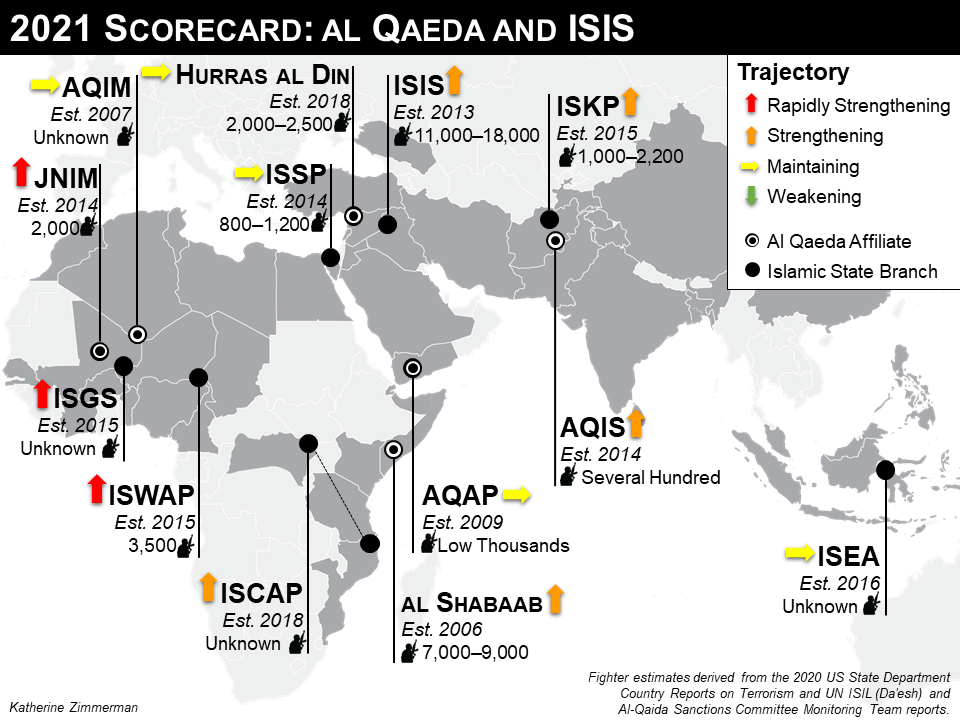

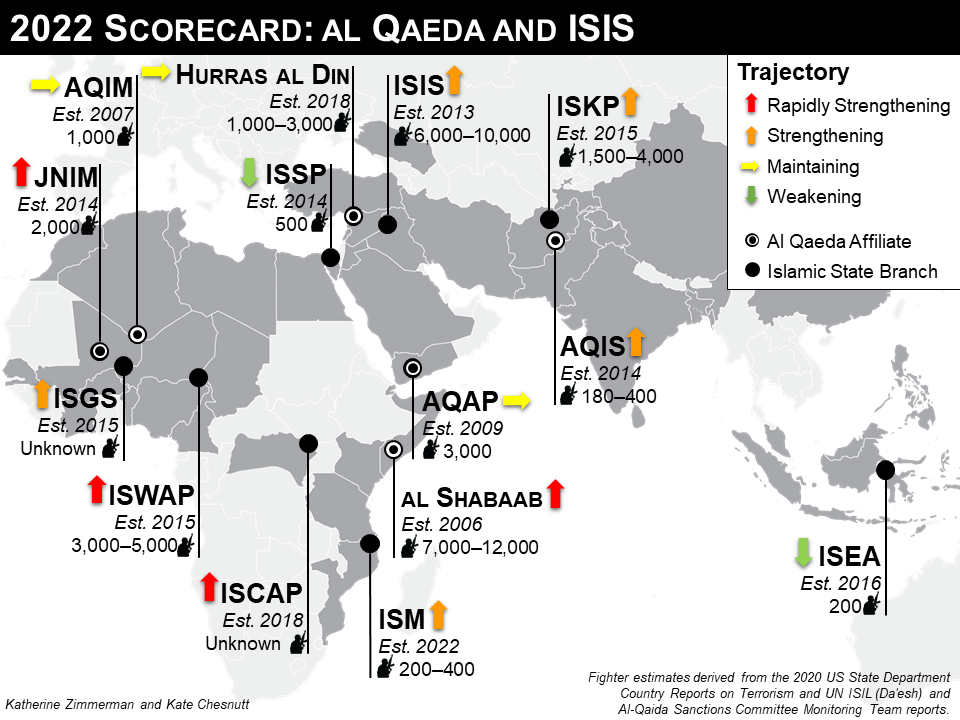

Note: The established date for each group is given in the figure with the abbreviation “Est.” The groups shown are al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP), Islamic State East Asia (ISEA), Islamic State Sahel Province (ISGS), Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham (ISIS), Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), Islamic State Mozambique (ISM), Islamic State Sinai Province (ISSP), Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), and Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM). Note that ISGS was renamed “Islamic State Sahel Province” in March 2022. For clarity, ISGS will continue to refer to the Sahel Province while ISSP will refer to Islamic State Sinai Province.

Behind the Scorecard

Africa: Salafi-jihadi groups have expanded rapidly in Africa. They have sustained local attack cells and broader insurgencies by capitalizing on local instability and governments’ inability to provide security and services, including drought and famine response.

In East Africa, al Shabaab’s insurgency in Somalia endures. Al Shabaab controls significant parts of south-central Somalia and has escalated attacks in the capital region since early 2022. It capitalized on diminished counterterrorism pressure caused by the withdrawal of US troops in 2021. Pressure on al Shabaab has increased since the reinsertion of US forces in May 2022, but its gains will take time to reverse. Additionally, al Shabaab conducted two military incursions into Ethiopia in summer 2022, indicating an intent to expand regionally. The Somali Islamic State province is relatively small but serves as an intermediary and financial hub for multiple Islamic State branches. It links the Islamic State’s central and east African provinces to Islamic State leadership in Iraq and Syria and transmits funds to Afghanistan via Yemen.

In May 2022, Islamic State leadership declared the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) and the Islamic State in Mozambique (ISM) autonomous, rather than two wings of the same province. Both ISM and ISCAP may benefit from their connection to IS leadership, which may push them to focus on a broader regional approach or increase their emphasis on external operations.

Since 2020, ISM has been engaged in an insurgency in northern Mozambique. Mozambican, Rwandan, and Southern African Development Community forces dislodged ISM from key towns in 2021, but ISM has relocated, expanded its activities elsewhere in the region—including increasing cross-border attacks into Tanzania—and encouraged fighters to melt into civilian communities until called on.

In northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, ISCAP has pursued a low-level insurgency for several years, prompting the declaration of martial law in two provinces in 2021. Ugandan and Congolese forces engaged in a concerted counterterrorism effort in late 2021 and early 2022, prompted by ISCAP attacks in Uganda, but ISCAP’s frequency of attacks has held steady. Over the past two years, ISCAP has effectively doubled its area of operation, increased its operational tempo, and attracted more foreign fighters. It has also freed upward of 2,000 prisoners in major prison breaks since 2020.

In North Africa, the Islamic State Sinai Province (ISSP) continues to conduct attacks against gas pipelines and the Egyptian armed forces but has declined in strength due to persistent Egyptian counterterrorism pressure and the resolution of underlying local grievances. The leader of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) remains in Algeria, but its focus has been the success of its subordinate affiliates in the Sahel, primarily Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM). AQIM appears to operate as a link to al Qaeda’s global leadership and a financial and ideological facilitator, although it has not exhibited significant independent operational capacity in recent years.

In West Africa, JNIM has embedded itself in communities in central Mali, providing aspects of governance, including administering justice, brokering interethnic peace deals, and imposing taxes. From this stronghold, it launched a series of attacks in southern Mali in summer 2022 and actively threatens security in Bamako, Mali’s capital. The withdrawal of French forces from Mali and possible further easing of counterterrorism pressure will permit JNIM to further entrench itself in central and northern Mali. JNIM previously expanded into Burkina Faso and has attack cells in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Togo. JNIM’s population-centric approach better positions it to gain local support compared to its local Salafi-jihadi rival, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), known for its brutality.

In March, the Islamic State declared ISGS an autonomous province, recognizing it as the Islamic State Sahel Province. The group has struggled due to leadership attrition. Malian pressure and intergroup competition have forced ISGS to reevaluate current approaches, including agreeing to a truce with JNIM. But ISGS remains an active operator in Mali’s embattled eastern provinces and a major threat to civilians in western Niger and northern Burkina Faso.

In northeastern Nigeria, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) has absorbed or eclipsed much of Boko Haram, the group from which it originally splintered. Over the past year, ISWAP has increased in operational tempo and audacity, including a large-scale prison break in July 2022 on the outskirts of Abuja, Nigeria’s capital. Its insurgency in the northeast is ongoing, but a rise in operations in central Nigeria indicates it has begun to build networks and capacity outside of its current strongholds.

In northwestern Nigeria, al Qaeda–linked Ansaru appears to be making a resurgence after several years of dormancy. The group confirmed its loyalty to AQIM. Although it is not yet a major threat, its ascendency indicates growing al Qaeda influence in the region. It appears to be pursuing a population-centric strategy and has adopted the banditry tactics common to other militant groups in northern Nigeria.

Middle East: Counterterrorism campaigns have weakened Salafi-jihadi groups in Iraq and Yemen, though early indicators point to the groups reconstituting capabilities. Broader regional instability has set favorable conditions for Salafi-jihadi groups, particularly in Syria.

In Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) has exhibited resilience and persistence in the face of extensive counterterrorism operations. In Iraq, ISIS activities have declined in 2021 and 2022, but this may reflect a reorientation toward Syria to take advantage of growing instability and insecurity. ISIS has conducted several complex attacks, including a major January 2022 prison break in Hasakah, northern Syria, from its strongholds and training camps in the Syrian desert. Massive camps of displaced persons, many related to imprisoned ISIS fighters, may further stress security in Syria. The loss of multiple senior Islamic State leaders, both killed and captured, has weakened the global Islamic State leadership cadre operating from Iraq and Syria.

Hayat Tahrir al Sham controls significant territory in northwestern Syria and has made a concerted effort to portray itself as moderate and legitimate, distancing itself from its Salafi-jihadi roots. It has consolidated power by targeting Hurras al Din—also known as al Qaeda in Syria—and occasionally the Islamic State in Idlib province, where Hayat Tahrir al Sham is the de facto governing body. It has pledged to provide services and defend those under its jurisdiction, and it exerts market controls and extracts taxes. Hurras al Din still professes strong loyalty to al Qaeda. It has been weakened over the past few years, though it remains active.

In Yemen, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) continued to strengthen slowly under reduced counterterrorism pressure. The group is more fragmented, but it remains focused on regenerating transnational attack capabilities, fighting the Houthis and local opposition and inspiring lone-wolf attacks in the US and Europe. The Islamic State in Yemen remains on a downward trajectory. Its key value to the global Islamic State network is its role as a financial and facilitation link between IS-Somalia and Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) in Afghanistan.

South Asia: Salafi-jihadi groups in the region have strengthened considerably since the August 2021 withdrawal of US and NATO forces from Afghanistan. Al Qaeda and al Qaeda–linked groups enjoy increased freedoms under the Taliban, while ISKP has strengthened. In Indonesia and the Philippines, counterterrorism efforts have been successful at degrading Islamic State cells. Major attacks have decreased substantially, though some pockets of militancy remain.

In Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Taliban has reestablished a safe haven for al Qaeda and al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) since the withdrawal of US and NATO forces in August 2021. Al Qaeda has not yet seen an increase in external operating capacity, but the apparent freedom with which al Qaeda leadership operates in Afghanistan indicates that recruitment, training, and propaganda operations are likely to increase. Some counterterrorism successes, such as the targeting of the late al Qaeda emir Ayman al Zawahiri, may be disruptive in the short term, but counterterrorism pressure has diminished substantially.

AQIS has maintained a low profile and individual fighters remain part of Taliban combat units. The Haqqani network retains its role as a regional facilitator and link between various regional Salafi-jihadi groups, with close ties to the Taliban and al Qaeda. Notably, the Haqqani network’s leader is a cabinet member in the new Taliban government and has been implicated in harboring Zawahiri. The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, while engaged in ongoing negotiations with the Pakistani government, has benefited substantially from Taliban leadership in Afghanistan. Splinter groups have rejoined the primary organization, and in March 2022, it announced a spring offensive against Pakistani security forces.

ISKP reconstituted over the course of 2021, taking advantage of Afghanistan’s instability in the wake of the Taliban takeover. The Taliban’s counterinsurgency operations against ISKP have had mixed results as ISKP focuses on undermining Taliban control, attacking infrastructure and targeting sectarian and ethnic divisions in Afghanistan and reestablishing former strongholds. ISKP’s ranks have swelled due to fighters’ release from prison during the Taliban’s summer 2021 offensive and increased recruitment afterward. The Islamic State has increased its funding for ISKP.

In Southeast Asia, authorities have made a significant impact on the operational capacity of Islamic State–linked groups, although they still pose a threat. In the southern Philippines, some pockets of activity remain, and periodic clashes with government forces and small-scale attacks continued.

Leadership: A decapitation approach has strained al Qaeda’s and the Islamic State’s leadership cadres, though both have proven resilient to attrition. The Islamic State has routinized its leadership succession, but turnover in the group’s senior leadership has helped weaken its ties to its regional branches, resulting in forced delegation of authority to local leaders. Al Qaeda’s already decentralized structure limits the impact of leadership deaths, but attrition in the ranks of its next generation of leaders may challenge the organization in the future. Newfound sanctuary in Afghanistan and the release of al Qaeda operatives from prison has enabled increased messaging from senior leaders to their global followers and added to the number of veteran operatives on the battlefield.

Key Salafi-jihadi leaders as of September 2022 include:

Al Qaeda

- Saif al Adel: A senior al Qaeda operative assessed to be the most likely new emir following the August 2022 death of Zawahiri. Adel spent significant time in Iran and may now be in Afghanistan.

- Abdul Rahman al Maghrebi: An al Qaeda shura council member, al Sahab media director, and head of external communications. He is believed to be in Iran. An alternate potential successor to Zawahiri.

- Abu Ubaydah Yusef al Annabi: AQIM’s emir, a longtime senior member. He succeeded Abdelmalek Droukdel after his death in June 2020.

- Khalid Batarfi: AQAP’s emir since 2020.

- Ahmed Umar (Abu Ubaidah): Al Shabaab’s emir since 2014.

- Iyad ag Ghaly: JNIM emir with long-standing ties to AQIM.

- Samir Hijazi: Hurras al Din’s leader.

- Osama Mahmood: AQIS’s emir since 2019.

Islamic State

- Abu al Hasan al Hashimi al Qurayshi: Islamic State leader and successor to Abu Ibrahim al Qurayshi, who was killed in February 2022. Possibly the nom de guerre of either Juma’a Awad Ibrahim al Badri or Bashar Khattab al Sumaidai, both high-ranking Islamic State leaders.

- Tamim al Kurdi: Leader of the Afghanistan-based al Siddiq office, appointed by Islamic State senior leadership in 2020.

- Abdul Bara al Sahrawi: ISGS’s emir, a seasoned logistical officer with experience operating in Libya. He replaced Adnan Abu Walid al Sahrawi after his death in August 2021.

- Abu Musab al Barnawi: Served as ISWAP’s emir between August 2016 and March 2019, before being appointed head of the Islamic State’s al Furqan office, which is based in the Lake Chad region and coordinates regional branches, in May 2021. His current status is unclear. The Nigerian government reported in September 2021 he had been killed, but unsubstantiated reports have since emerged that he remains alive.

- Musa Baluku: ISCAP’s leader in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- Abu Yasir Hassan: ISCAP’s leader in Mozambique, as identified by the US.

- Shahab al Muhajir: ISKP’s emir, an Iraqi who defected from the Haqqani network and al Qaeda and succeeded the group’s founder, Hafiz Saeed Khan, in April 2020.

- Abu Hajar al Hashemi: ISSP’s emir. He may have served previously as an Iraqi army officer.

- Abdul Qadir Mumin: IS-Somalia’s emir. He defected from al Shabaab.

- Abu Zacharia: Leader of ISEA.

Salafi-Jihadi attacks with American Casualties (2021–22)

Salafi-jihadi groups such as al Shabaab, AQAP, and ISIS have pursued external attack capabilities but have not conducted a terror attack in the US since the December 2019 shooting in Pensacola, Florida. The most recent attack against US forces was the ISKP suicide attack in Kabul, Afghanistan, in August 2021. US forces on counterterrorism missions are no longer engaged in combat operations, limiting the opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to target them. Salafi-jihadi groups have targeted Westerners in kidnapping-for-ransom plots. In late August 2022, US special operations forces rescued an American kidnapped in Burkina Faso in April 2022.