{{currentView.title}}

June 26, 2014

Yemen's Counter-Terrorism Quandary

Introduction

President Obama has called Yemen a “committed partner” in the fight against al Qaeda and has spoken of his intention to apply the “Yemen model” to Iraq and Syria.[1] Such declarations ignore the forces threatening the survival of the Yemeni state, particularly the insurgency known as the al Houthi movement that is currently advancing on Yemen’s capital, Sana’a. Yemen is America’s partner in the fight against al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) – a group that has tried to attack the U.S. repeatedly since its formation in 2009. Political unrest in 2011 in Yemen drove then-president Ali Abdullah Saleh to draw resources away from the south. AQAP seized the chance to strengthen itself and expand its safe havens dramatically.[2] Yemeni efforts since then, with very limited support from the U.S., have reduced AQAP’s control, but the escalating conflict with the al Houthis threatens to divert key resources away from the counter-terrorism fight once again.

The al Houthis have been battling the Yemeni government since 2004. They declared a truce with the government in 2010, but never really gave up their cause. Yemen’s much-heralded political transition process after the Arab Spring revolt that drove Saleh from power failed to mollify the al Houthis, who have renewed their fight against Saleh’s successor, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, in response. The al Houthi return to arms directly challenges the Yemeni state as they fight to expand their territory southward. It may even undermine the extremely fragile and incomplete political agreements that ended the Arab Spring uprising. In the worst case, it could initiate the collapse of a unitary Yemeni state. An escalation of the al Houthi conflict also raises the question of Iran’s role in supporting the al Houthis, which has notably increased over the past few years.

The Arab Spring: A Chance for al Houthi Expansion

The al Houthi movement started as a political movement during the 1990s under the leadership of Hussein Badr al Din al Houthi with the goal of reviving Zaydism, a Shiite sect that believes only descendants of the Prophet Mohammed can be Muslim rulers. The Yemeni government attempted to arrest Hussein in September 2004, but killed him during the process. His death sparked an armed uprising, which became known as the al Houthi movement. The movement fought six separate wars, known as the Sa’ada Wars, against the Yemeni government between 2004 and 2010.[3] The government and the al Houthis negotiated a fragile ceasefire in February 2010. The ceasefire ended hostilities, but the government never addressed the movement’s core grievances.[4]

The Arab Spring uprisings collapsed the Yemeni state and especially its security forces into Sana’a in 2011, creating an opening for the al Houthis to carve out their own territory in north Yemen, starting in Sa’ada. The al Houthis appointed a new governor and assumed local administrative roles there, effectively establishing their own statelet.[5] Iranian support for the al Houthis increased following the 2011 uprisings when Yemen was in one of its most fragile states. Anonymous American military and intelligence officials stated in March 2012 that Iranian smugglers backed by the Quds Force had shipped weapons to rebel groups in Yemen, including the al Houthis.[6] The al Houthis spokesperson, Mohammed Nasser al Bukhaiti, confirmed that the president of the al Houthis’ political party, Ansar Allah, met with the Iranian ambassador in Sana’a on May 10, 2013.[7] The al Houthis continue to deny any allegations that Iran supports them.[8]

The Yemeni Arab Spring resulted in a Gulf Cooperation Council political transition plan that led to Saleh’s resignation. The plan created a national dialogue process known as the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) in order to resolve multiple national issues.[9] The al Houthi movement agreed to participate in the NDC as a way to further its political agenda and sent representatives from Ansar Allah as delegates to the NDC in 2013.[10] The al Houthis began voicing objections to the NDC in mid-January 2014 after the council pushed through a mandate allowing President Hadi to form a committee to decide the number of regions in Yemen.[11] Tensions escalated further when the al Houthis’ NDC representative, Ahmad Sharaf al Din, was assassinated in the capital before the final plenary session and closing ceremony of the NDC on January 21.[12] President Hadi went ahead with the plenary session despite Sharaf al Din’s death and rushed through an agreement on the Southern Issue (the relationship of the territories of the former South Yemen with the rest of the Yemeni state).[13]

The al Houthis in turn withdrew from the NDC and boycotted the final session. They objected to a change from consensus to majority vote on the document that finalizing the mandate to decide the number of federal regions. They claimed that the NDC’s final outcomes were decided hurriedly and without their input.[14] President Hadi officially announced the plan to divide Yemen into a six-region federation a few weeks after the close of the NDC on February 10, 2014.[15] The al Houthis were quick to reject the President’s plan, arguing that it would divide Yemen into rich and poor regions and leave Sa’ada landlocked and with no significant resources. The plan also split al Houthi territory into two, separate regions, to which the al Houthis strongly objected.[16]

2014 Winter Offensive

The al Houthis not only see themselves as politically marginalized, but they also see their Zaydi Shiite identity threatened by growing Saudi-backed Salafi influence in their tribal stronghold, Sa’ada. Some tribes in Sa’ada since the 1990s have adopted the Salafi branch of Sunni Islam, leading to the decline of Zaydism in northern Yemen.[17] Al Houthis besieged one of the largest Salafi religious centers in Yemen, Dar al Hadith, in Dammaj, on October 30, 2013, accusing Salafis in Dammaj of recruiting foreign fighters.[18] Fighting continued intermittently in Sa’ada until both sides reached a ceasefire in January 2014, stipulating that non-local Salafis leave Dammaj.[19]

The al Houthis took their fight south during the beginning of January 2014 to strongholds of the Hashid tribal confederation, whose members the al Houthis accuse of supporting Salafis in Sa’ada. The al Houthis attacked villages in the Khaywan Valley, north of Amran city, beginning on January 6.[20] Clashes continued until the al Houthis finally overran strongholds of the leading family of the Hashid tribal confederation, the al Ahmars, in Huth and al Khamri on February 2 under the pretext that an al Ahmar sheikh forbade Hashid tribal members from joining the al Houthis.[21] The al Houthis simultaneously clashed with tribes in Arhab beginning on January 25, 2014, and took control of nearby Raydah on February 5.[22] The al Houthis agreed to a ceasefire on February 9, at which point clashes became less frequent for the remainder of February.[23]

Fighting flared up again when al Houthi militants began fighting with the Yemeni military and tribes in al Jawf in northern Yemen between February 28 and March 10. Clashes with the military spread south to Hamdan March 9.[24] The militants then held a protest in Amran on March 14, demanding the resignation of the governor of Amran, Mohammed Hassan Dammaj, and the commander of the 310th Armored Brigade, Hamid al Qushaybi.[25] Al Houthi fighters attempted to enter the city of Amran again on March 22 in order to stage a second round of anti-government protests. Government forces fired on the group, resulting in the deaths of six rebels.[26] A presidential commission brokered a two-week peace with the al Houthis following their failed entry into Amran city, and fighting subsided for the month of April.[27]

A Renewed Push South

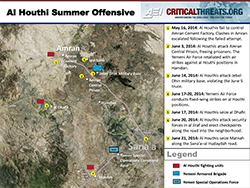

Local reports indicated as early as mid-April 2014 that al Houthis were planning an offensive in Amran and Arhab.[28] Renewed clashes broke out on May 14 between al Houthi militants and the 310th Armored Brigade when militants attempted to control a cement factory located in al Hajaz, close to the 310th Armored Brigade’s base in Jebel Dhin. A presidential committee brokered a short-lived ceasefire on May 23. Clashes escalated on May 25 between al Houthi militants and the 310th Armored Brigade in al Jannat and the al Mekshash Mountains, when al Houthis attacked the military’s positions and buildings owned by the al Ahmar family.[29]

|

The al Houthis attacked Amran central prison on June 3 and freed around ten al Houthi inmates along with 400 others, according to Yemeni sources. Tribal militias affiliated with the al Islah party and the 310th Armored Brigade attempted to expel the al Houthis from the area around the prison.[30] The Yemeni military conducted airstrikes the same day on al Houthi positions in Amran.[31] The airstrikes marked a change in the Yemeni military’s response to the conflict since, up until that point, the military had only been involved in ground engagements with the al Houthis.

A committee formed by President Hadi and chaired by the Minister of Defense, Maj. Gen. Mohammad Nasser Ahmad, negotiated a ceasefire on June 5 following the airstrikes.[32] Even Abdul Malik al Houthi, the leader of the al Houthis, expressed willingness to implement the ceasefire and release captured soldiers. In exchange, Abdul Malik called for the government to replace the 310th Armored Brigade, the same brigade that was heavily involved in fighting the al Houthis during the Sa’ada Wars.[33] The Yemeni government replaced the governor of Amran, Mohammed Dammaj, with whom the al Houthis had also expressed dissatisfaction. However, the government did not meet the main al Houthi demand that Hamid al Qushaybi, whom the al Houthis have accused of supplying Salafis in Dammaj with weapons, be replaced and that the 310th Armored Brigade be removed from Amran.[34]

The al Houthis broke the June 5 ceasefire on June 14 and attacked the 310th Armored Brigade’s military base in Jebel Dhin, located along the road from Sana’a to Amran.[35] The al Houthis then carried out an offensive in Jebel al Dhafir, approximately 30 km northwest from Sana’a. Militants seized a road and blew up three houses in the village of al Dhafir on June 17. The militants proceeded to clash with the tribes around al Dhafir and from Bani Matar during the week, but at the time of writing appear to be holding the village of al Dhafir.[36]

Continued efforts, even at the presidential level, to de-escalate the conflict have failed. The al Houthis continued the week of June 17 to clash with the 310th Armored Brigade and tribes supporting the al Islah party in Hamdan, Sana’a, and Jebel al Dhafir despite a public warning from President Hadi not to escalate the conflict.[37] The Yemeni military responded by sending Special Forces to assist the 310th Armored Brigade and continued airstrikes on al Houthi positions in Iyal Sarih on June 17 and 20.[38] The al Houthis responded to the airstrikes with a post on its website, Ansaru Allah, on June 19 comparing the Yemeni military’s current actions with the six Sa’ada Wars.[39]

The al Houthis moved their fight farther south to the capital of Sana’a during June 20 and 21. An explosion occurred at the house of a Salafi sheikh the night of June 20 in al Jiraf, a neighborhood in northern Sana’a along the road to al Daylami Air Force Base.[40] Al Houthi militants later stated that security forces attacked their political office in Sana’a city, justifying the erection of checkpoints along the entry road into al Jiraf. Al Houthi militants attacked a group of security forces following the explosion.[41] Government sources confirmed that al Houthis had seized control of Sana'a's Bani Matar district capital, Matnah city, on June 21, which is along the road from Sana’a to al Hudaydah.[42] Both Ansaru Allah and the Yemeni military’s outlet published terms of a ceasefire on June 22, but neither side signed the agreement. Clashes between the 310th Armored Brigade and al Houthi militants continued in Hamdan and Bani Matar the evening of June 22 and into June 23.[43]

At the time of writing, it appears that the al Houthis continue to hold their positions in Hamdan and al Dhafir. A local source reported that the 310th Armored Brigade withdrew from its position in al Dhafir on June 19. Tribes located in al Dhafir have attempted to negotiate a ceasefire between the 310th Armored Brigade and al Houthi militants, but all mediations have failed.[44]

Yemen’s Rocky Political Landscape

It is not clear what will appease the al Houthis or whether their terms would be acceptable to the current government. Abdul Malik al Houthi’s public willingness to negotiate on June 3 signals that there is a glimmer of hope in resolving the conflict. It is clear that the presence of the 310th Armored Brigade and its commander, al Qushaybi, are unacceptable to the al Houthis. It is also clear that the al Houthis will stand by their rejection of the proposed six-region federation. The al Houthis continue to seek inclusion in the political process and want recognition of their cause.

The conflict between the al Houthis and the 310th Armored Brigade is not easy to solve, however. The 310th Armored Brigade was part of General Ali Mohsen al Ahmar’s 1st Armored Division before Hadi issued restructured the military in 2012 and still remains loyal to Ali Mohsen.[45] Ali Mohsen, who commanded the Yemeni military units fighting the al Houthis between 2004 and 2010, is now a presidential adviser for military affairs.[46] He and the al Ahmar family (no relation) are aligned against the al Houthis. There are rumors that Ali Mohsen is at odds with the Defense Minister, Mohammed Nasser Ahmed.[47] The political dynamics in the capital place Hadi between a rock and a hard place. Hadi would probably need support from Ali Mohsen to redeploy the 310th Armored Brigade out from Amran, which he is unlikely to receive. On the other hand, the al Houthis accuse Hadi of having the same mentality as the old regime.[48] Hadi’s predecessor, Saleh, almost had a chance at ending the conflict in 2010, but would accept nothing less than an unconditional surrender from the al Houthis.[49] Hadi will need to find a way forward that would be acceptable to the al Houthis, Ali Mohsen, and the al Ahmars.

The escalation in the al Houthi conflict also comes at a time when fears are growing that Iran and Saudi Arabia could enter a proxy war with each other in the Middle East.[50] Saudi Arabia fought the al Houthis along its southern border during the Sa’ada Wars. The Iranians have provided some material support for the al Houthis following the fall of Saleh. Yemen could become another battleground in addition to Iraq and Syria, where Iran and Saudi Arabia fight for influence.

A Threat to U.S. Counter-Terrorism Strategy

The United States’ current counter-terrorism strategy in Yemen rests on continued commitment from the Yemeni government and President Hadi. The al Houthi conflict puts Hadi in a quandary. If Hadi cannot get both sides to compromise soon, clashes will continue to escalate. Continued escalation in the al Houthi conflict increases the threat to Hadi and his government and will most likely draw limited resources away from fighting AQAP. Such a shift in military resources to the al Houthi conflict could give AQAP uncontested safe havens in southern Yemen, where it could plan and coordinate attacks against the U.S. This scenario exposes the weakness in a counter-terrorism strategy that relies on foreign partners to combat terrorist groups. An al Houthi offensive against the Yemeni government spells disaster for combating AQAP.

Please note that this piece was updated on July 29, 2015, to reflect the correct date of death for Ahmad Sharaf al Din. He was killed in Sana'a on January 21, not June 21, 2014.