Salafi-Jihadi Global Tracker

The Salafi-Jihadi Global Tracker provides analysis and assessments of major developments related to the Salafi-jihadi movement.

Loading...

Loading...

Salafi-Jihadi Global Tracker: Islamic State Affiliates Pledge to New Leader

Key Takeaway: Islamic State affiliates have released pledges of allegiance to the new IS leader following the prior leader’s death in October. The pledges did not indicate a significant change in the loyalties of IS affiliates or their capabilities or territorial reach. Two unofficial pro-IS groups also released pledges to the new leader. Some affiliates may increase attacks in revenge for the killing of the IS leader, mirroring prior surges of activity after leadership changed.

The Islamic State announced the death of its leader and named a successor on November 30. IS announced on November 30 that its new overall leader is Abu Husayn al Qurayshi. Local Syrian armed groups killed late IS leader Abu Hassan al Qurayshi in mid-October in southwestern Syria. Abu Hassan al Qurayshi had been the leader of IS since March 2022. IS claimed that Abu Husayn al Qurayshi is a veteran jihadist but did not provide any additional information on him. This secrecy is typical of recent IS leadership appointment announcements. IS likely announced the leader in response to an anti-IS media channel claiming on November 29 that the IS leader had died. Pro-IS online accounts also participated in a spontaneous repledging campaign in late November, possibly due to rumors of an IS leadership change.

IS affiliates participated in a pledge campaign to show support for the new IS leader. IS affiliates in Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Egyptian Sinai, India, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen have pledged allegiance to the new IS leader as of December 23. These pledges reaffirm the affiliates’ loyalty to IS following the death of the prior leader, to whom each affiliate had also sworn a personal oath. The pledges are also an opportunity for IS to assert to current and potential fighters that it is a unified and expanding global movement.

Pledges from the Islamic State’s Nigerian affiliate confirm the group’s growing networks in central Nigeria. Six Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) branches have pledged allegiance to the new IS leader since December 1. ISWAP released a pledge on December 5 from a new ISWAP subgroup in central Nigeria. The pledge shows three photosets with 11 fighters. This network is likely small and lacks access to weapons; one fighter is holding a pistol, but no other weapons are displayed. The central Nigeria branch was also the only ISWAP subgroup to photograph their pledges indoors, perhaps suggesting this group is not secure enough to gather outdoors. The addition of a new group since the previous pledge campaign in March highlights ISWAP’s growing presence in central Nigeria. ISWAP claimed its first attacks in central Nigeria in April 2022 and has carried out numerous attacks in the region since.[1] ISWAP was also likely responsible for an attack plot in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, in late October. ISWAP’s pledge from central Nigeria illustrates ISWAP’s desire to highlight its expansion into new areas of that country.

Figure 1. Islamic State Affiliates and Pro–Islamic State Groups in Africa Pledge Allegiance to a New Leader: December 2022

Source: Author.

IS pledges from the Sahel and Mozambique reaffirm these affiliates’ organizational changes but do not demonstrate expansion. The Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISGS) and the Islamic State in Mozambique (IS-Mozambique) released their own pledges of allegiance for the first time after having pledged as part of other IS affiliates in March 2022. IS recognized ISGS and IS-Mozambique as official, independent branches in March and May 2022, respectively.[2] Before this, ISGS claimed attacks and pledged to new leaders as part of ISWAP. IS-Mozambique similarly claimed attacks and released pledges as part of the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP).

ISGS’s first pledges confirm it maintains its independent status from ISWAP. ISGS militants in the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger pledged on December 3, and fighters based in Menaka, northeastern Mali, pledged on December 4. The photosets do not indicate a significant change in ISGS fighter numbers or weapons capacities since March 2022. ISGS likely seeks to formalize its presence in Menaka, but its pledge in this region does not mark an ISGS expansion to new areas. Neither ISGS nor ISWAP pledged from Menaka in March 2022, but ISGS has claimed offensives and regular attacks in this area in 2022 and has been intermittently active around Menaka since the group’s formation.

IS-Mozambique pledged separately from ISCAP for the first time on December 6–7.[3] IS-Mozambique’s pledge validates its operational autonomy from ISCAP and shows a continuation of where IS-Mozambique operates. The photoset from December 6 does not name a location, but the December 7 photoset indicates that IS-Mozambique fighters are based in Nangade, northern Mozambique, where IS-Mozambique has recently attacked. IS-Mozambique may be naming this location because it continues not to perceive a strong threat from counter-IS forces in this area.

Pro-IS militants in Tunisia and Lebanon pledged to demonstrate their ongoing relevance and connection to the broader IS network. IS has never recognized branches in Tunisia or Lebanon as official IS affiliates, likely because of the groups’ inability to conduct frequent or high-profile attacks. Pro-IS fighters in Tunisia released a pledge to the new IS leader on December 7. Tunisian fighters last released a pledge to IS in 2019. The photoset shows four fighters in a room without weapons. Pledges from pro-IS fighters in 2019 boasted comparatively more weapons and manpower in an open-air location than in the December pledge. It is not clear whether the individuals in the 2022 pledge belong to the same group as the 2019 pledge. Tunisian counter-IS operations have significantly weakened the group in recent years.

Pro-IS fighters in Lebanon also pledged to the new IS leader on December 8. The fighters released three photosets showing a total of 17 militants. Pro-IS fighters based in Lebanon have never participated in a pledge campaign, but IS has claimed rare attacks in Lebanon in the past, the most recent of which was a shooting against security forces in May 2019.[4] It remains unclear whether the fighters pledging now have participated in previous attacks in Lebanon, however. IS is unlikely to elevate groups in Tunisia or Lebanon to official affiliate status due to those groups’ continued lack of fighters and resources and inability to attack. The photosets from Tunisia and Lebanon show that IS maintains a physical, though small and disparate, presence in these countries and highlights these fighters’ desire to remain connected to the larger IS movement.

Figure 2. Islamic State Affiliates and Pro–Islamic State Groups in the Middle East and Asia Pledge Allegiance to a New Leader: December 2022

Source: Author.

The Islamic State may attempt to coordinate a named attack campaign to commemorate its late leader, and some affiliates may surge attacks. IS affiliates participated in a named attack campaign in April 2022 to avenge the death of late leader Abu Ibrahim al Qurayshi in March 2022, and IS affiliates may attempt the same after the killing of Abu Hassan al Qurayshi. IS increased its attack rate during the spring attack campaign, as compared to previous months, though local dynamics and affiliates’ preexisting objectives likely contributed to this uptick. IS may have timed the April attack surge to coincide with the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, during which the group has surged attacks in previous years. IS could delay an attack campaign to avenge the death of Abu Hassan al Qurayshi until Ramadan in March 2023, but this would mark an increase in the lag between the death of an IS leader and an IS announcement of a global attack campaign. IS only delayed approximately one month after announcing the death of its leader before declaring the attack campaign in April 2022.

[1] SITE Intelligence Group, “ISWAP Claims Bombing at 2nd Bar in Taraba, Expands Operations in Nigeria to Kogi State,” April 23, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[2] SITE Intelligence Group, “Using New ‘Sahel Province’ Designation, IS Claims Attack on Malian Army Base in Gao,” March 22, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Gives Mozambique ‘Province’ Status, Claims 3 Soldiers Killed in Raid in Cabo Delago,” May 9, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[3] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Fighters in DR Congo, Mozambique, Pakistan, and More from Syria Pledge to New Leader,” December 6, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[4] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Identifies Executor of Eid al-Fitr Eve Attack in Tripoli as One of its ‘Soldiers’ in Naba 189,” July 4, 2019, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

Salafi-Jihadi Global Tracker: Al Shabaab Besieges Hotel Near Somali Presidential Complex

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

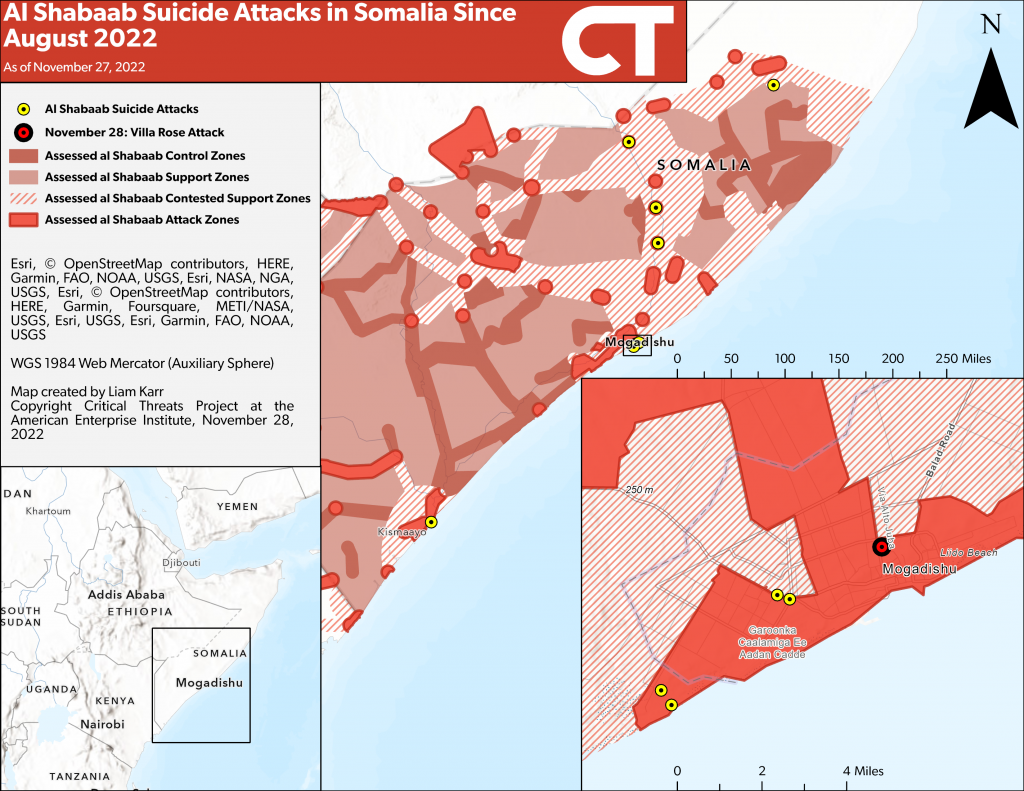

Key Takeaway: Al Shabaab besieged a hotel within a mile of Somalia’s presidential palace on November 27. The siege is the latest in a series of high-profile suicide attacks across Somalia in response to an ongoing government-led campaign to recapture al Shabaab positions in central Somalia.

Al Shabaab besieged the Villa Somalia presidential complex on November 27. At least one suicide bomber and five more militants breached and laid siege to the Villa Rose hotel, which government officials frequent. The militants killed at least eight civilians and one police officer Security forces ended the siege on November 28 after 20 hours.

The Villa Rose attack is the latest in a string of al Shabaab suicide operations across Somalia since August. Al Shabaab carried out its deadliest attack since 2017 on October 29, killing over 100 people in a suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) attack targeting an education ministry building in Mogadishu. The Villa Rose attack is the third hotel suicide siege in southern Somalia since August, following raids in Mogadishu and Kismayo that killed 32 people in total. The group has also carried out several VBIED attacks in central Somalia over the same period.

The Mogadishu attacks demonstrate that al Shabaab retains key capabilities in and around the Somali capital. The August 19 hotel siege and October 29 bombing and occurred two miles west of Villa Somalia in the Kilometer 4 (KM4) area. Attackers must bypass multiple security checkpoints to strike near KM4 and Villa Somalia, indicating shortcomings in the existing security measures in Mogadishu and likely al Shabaab infiltration of security organizations. The attacks also indicate that the group maintains strong support zones in Mogadishu’s outskirts despite government efforts* to disrupt* these staging zones in September and November 2022.

Figure 1. Al Shabaab Suicide Attacks in Somalia Since August 2022

Source: Liam Karr.

Al Shabaab will likely continue to conduct suicide attacks targeting civilians in response to federal forces and local militias’ offensive against its positions in central Somalia. Somali National Army (SNA) units and anti–al Shabaab clan militias have since August ousted al Shabaab from dozens of villages in central Somalia, including several* al Shabaab strongholds* that the group has held for years. The Somali prime minister claimed on November 23 that these operations have killed more than 600 militants and injured 1,200 others. Al Shabaab has framed the Villa Rose siege and its other suicide attacks as retaliation for this counterterrorism offensive.[1] Al Shabaab will likely continue high-profile attacks to undermine political will and popular support for continuing the offensive.

[1] SITE Intelligence Group, “UPDATED: Shabaab Executes Suicide Raid at Presidential Palace Compound in Somali Capital, Storms Villa Rose Hotel,” November 28, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; SITE Intelligence Group, “Justifying Twin Suicide Bombings at Somali Education Ministry, Shabaab Alleges Enemy Recruiting Students into Military,” October 30, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; and SITE Intelligence Group, “At the End of Hayat Hotel Raid, Shabaab Boasts 170 Casualties in Longest Such Hotel Attack Waged by Fighters,” August 21, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

Islamic State Increases Attacks as Pakistani Taliban Negotiates

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

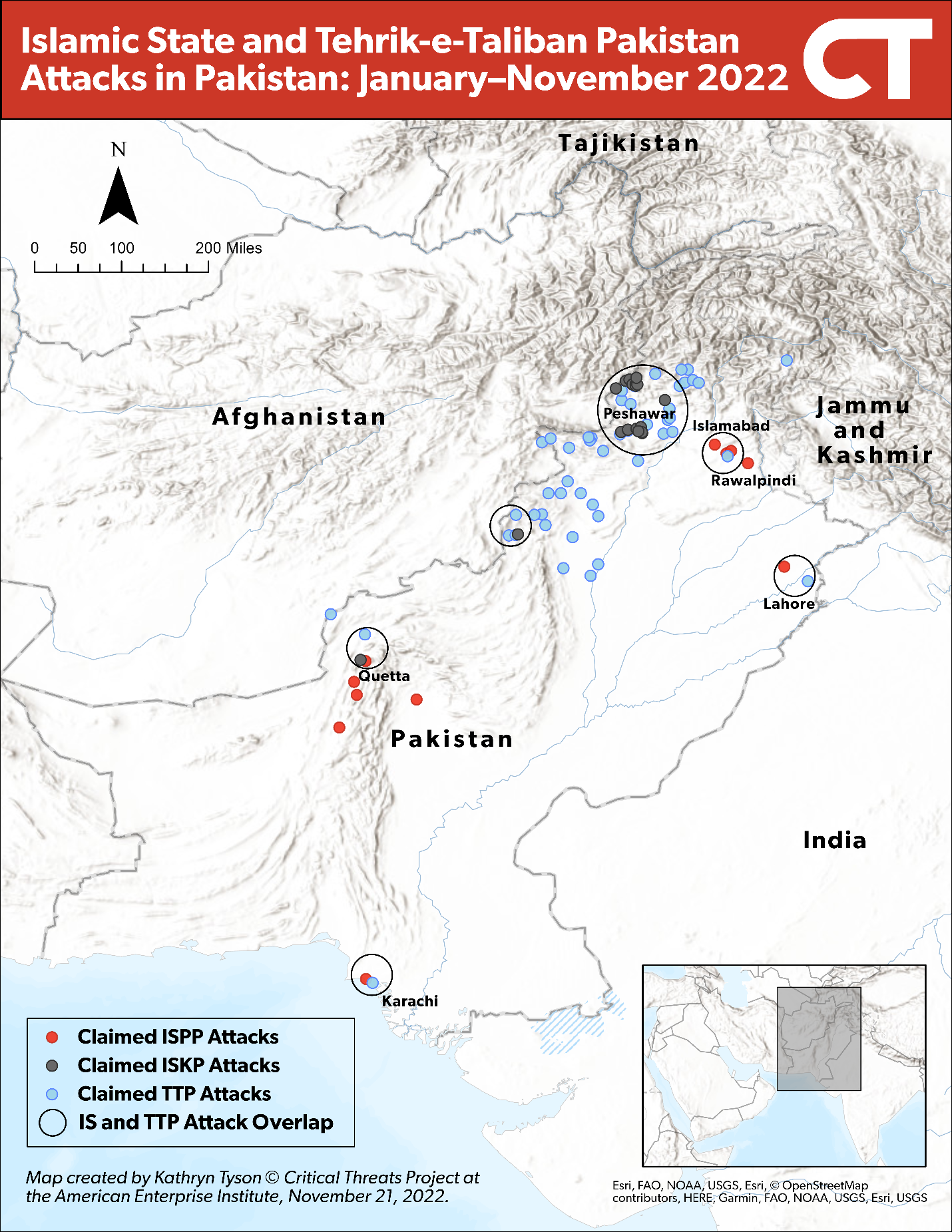

Key Takeaway: The Islamic State’s Pakistan Province (ISPP) is attempting to recruit from the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) as the TTP negotiates with the Pakistani government. ISPP has increased attacks since negotiations began in November 2021. The group also demonstrated renewed attack capabilities in October 2022, though its overall effectiveness remains limited. Government concessions to the TTP could also benefit ISPP and other Salafi-jihadi groups by increasing their access to safe havens in northwestern Pakistan.

The Islamic State’s Pakistan Province (ISPP) poses a latent threat in South Asia’s crowded militancy landscape but benefits from its integration with more-established groups. The Islamic State established ISPP in May 2019 by dividing the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) into separate branches for Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan. ISPP has since struggled to capitalize on local dynamics and establish footholds. It has likely survived due to its ongoing coordination and overlapping networks with ISKP. The UN reported in May 2022 that ISKP is co-located with the Islamic State’s al Siddiq administrative office, which oversees Islamic State affiliate activities throughout South and Southeast Asia. ISPP and ISKP are also allies with shared networks, and fighter loyalties to ISPP and ISKP are often blurred and fluid. Islamic State central directed ISKP in July 2021 to attack in northwestern Pakistan, where ISPP had previously operated, and ordered ISPP members in the northwest to begin following ISKP orders. ISPP and ISKP have largely maintained this division of operations.

ISPP and ISKP also have some overlying networks with the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an umbrella organization of anti-Pakistan militant groups affiliated with the Afghan Taliban and al Qaeda. ISPP’s current leader is a former TTP commander, and TTP defectors and other Pakistani militants formed ISKP in 2015. The UN reported in January 2020 that ISKP had established informal contacts with the TTP. ISPP, ISKP, and the TTP continue to claim some of the same attacks in Pakistan, which could point to a convergence in their operations and membership.

Figure 1. Islamic State and TTP Attacks in Pakistan: January–November 2022

Source: Author.

ISPP increased its rate of attacks in 2022 and has escalated attacks since September 2022. ISPP has claimed 15 attacks in 2022 so far, with eight of these attacks occurring in September and October. The group concentrated attacks in Balochistan province in southwestern Pakistan and Punjab province in eastern Pakistan. It has focused attacks in both provinces in previous years. This September–October surge is the largest number of ISPP attacks since 2019, when the group claimed 15 attacks. ISPP claimed approximately four attacks per year in 2020 and 2021. COVID-19 *lockdowns and a related increase in Pakistani military presence in these two provinces may have contributed to this lull.

ISPP returned to prior attack zones and renewed explosive attacks in October 2022. ISPP claimed to wound four security personnel during what was likely a raid on an ISKP hideout on October 1. This incident was ISPP’s first claimed attack in Karachi since May 2019. ISPP also used an improvised explosive device (IED) in an attack for the first time since May 2020. ISPP claimed it detonated two IEDs targeting alleged Pakistani intelligence agents in Mastung, southwestern Pakistan, on October 14. Most claimed ISPP attacks in 2022 have involved small-arms or grenade attacks. These attacks likely aim to degrade security forces’ abilities to disrupt ISPP or ISKP activities. ISPP also likely seeks to incite sectarian conflict by targeting religious minorities in attacks. The following is a list of ISPP attacks in 2022.

- January 30: An ISPP gunman assassinated a Pakistani policeman in Rawalpindi, Punjab.[i]

- March 8: ISPP detonated a suicide vest targeting Pakistani soldiers in Sibi, Balochistan, killing five soldiers and wounding 25 others.

- April 22: ISPP killed a “Christian” in Rawalpindi, Punjab.

- April 29: ISPP killed likely a Sufi in Mastung, Balochistan.

- April 30: ISPP killed likely a Sufi in Sheikhupura, Punjab.

- June 20: ISPP killed a “Shīʿah” in Islamabad.

- August 9: ISPP fired on a group of “Christians” in Mastung, Balochistan. The attack killed one person and wounded several more.

- September 19: ISPP fired on a Pakistani Counterterrorism Department (CTD) patrol and injured two CTD personnel in Quetta, Balochistan.

- September 30: ISPP killed likely a Sufi in Rawalpindi, Punjab.

- October 1: ISPP threw hand grenades and fired on CTD forces in Karachi, Sindh, and injured four CTD personnel.

- October 13: ISPP militants beheaded a Pakistani “informant” in Mastung, Balochistan.

- October 14: ISPP detonated two IEDs targeting Pakistani “spies” in Mastung, Balochistan. The attack killed three people and injured six others.

- October 21: ISPP killed a Pakistani “intelligence officer” in Rawalpindi, Punjab.

- October 25: ISPP killed a Pakistani police officer in Lahore, Punjab.

- November 12: An ISPP gunman killed a Pakistani “spy” in Qalat, Balochistan.

ISPP’s recent surge may aim to attract militants from other groups, particularly TTP members disillusioned with their group’s willingness to negotiate with the Pakistani government. The TTP and the Pakistani government *reached a temporary cease-fire in November 2021 and an indefinite cease-fire in June 2022. ISPP may be attempting to position itself as the main jihadist alternative to the TTP. ISPP condemned the TTP, al Qaeda, and the Afghan Taliban for abandoning jihad in December 2021 and again in August 2022. This criticism likely referred to the TTP’s negotiations with the Pakistani government, which the Afghan Taliban and members of the al Qaeda–linked Haqqani network have facilitated. ISPP also called on TTP members to disobey TTP leadership supporting negotiations with the Pakistani government, possibly encouraging defections. ISPP could recruit hard-line TTP members who oppose negotiations. ISKP similarly used the 2020 negotiations between the Afghan government and the Afghan Taliban to act as a spoiler and gain recruits. The TTP has reunited 10 splinter factions since 2020 after years of internal fighting, but the group remains decentralized and could split again.

ISKP’s comparative recruiting advantage may dampen ISPP’s ability to attract TTP fighters. ISKP and ISPP are linked groups that coordinate activities and share networks, but their overlap could have unintended trade-offs. ISKP, like ISPP, criticized the TTP over negotiations in July 2022 to attract TTP defectors. ISKP has also successfully recruited from the TTP in the past, and ISKP and the TTP currently operate in the same areas. ISPP and the TTP still likely have some overlapping networks in this region. Both groups claimed two of the same attacks in 2022 in Punjab province, eastern Pakistan. ISKP and the TTP may have more shared networks than ISPP, however. ISKP and the TTP have claimed at least six of the same attacks in 2022. ISKP also has a more active propaganda wing than ISPP and has adopted an aggressive propaganda strategy to attract militants from South and Central Asia.

ISPP has taken new steps to build its base in Pakistan and finance its operations. ISPP launched its first Urdu-language magazine called Yalghar (Invasion) in April 2021 to attract recruits, rally members, and discredit opponents, publishing three issues since 2021. The magazine targets a general Pakistani audience rather than a particular ethnic group or population from a specific region in Pakistan, likely to appeal to a larger pool of potential recruits. The magazine also courts Urdu-speaking fighters from India and Kashmir. ISPP’s use of emerging technologies to solicit donations could also help the group expand in Pakistan. The Yalghar issue in August 2022 included QR codes directing users to Telegram accounts, marking the first pro–Islamic State publication that has marketed QR codes to their audience. ISPP could collect cryptocurrency donations through this Telegram account. The US government has reported instances of other Islamic State branches soliciting cryptocurrency, enabling these groups to expand and disguising their funding efforts.

ISPP poses a lesser threat than other militant groups in Pakistan, but it could expand its footholds if domestic unrest worsens. Public confidence in Pakistani state institutions and the military is declining, and political unrest in Pakistan will likely increase in the coming months. The attempted assassination of former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan on November 3 ignited *protests across Pakistan, including in areas where ISPP has recently attacked. ISPP could capitalize on local distrust for propaganda value and recruitment. ISPP blamed the Pakistani government in August 2022 for record-breaking flooding in Pakistan and called for attacks. ISPP will likely continue to target Pakistani security forces and religious minorities in an effort to undermine Pakistani governance and security and spark sectarian violence.

Concessions to the TTP could present new options for ISPP and the wider Salafi-jihadi movement in Pakistan. Islamabad seeks to dissolve the TTP and transition it into mainstream politics. Pakistani negotiators indicate openness to some TTP demands, including a reduction of Pakistani military forces from northwestern Pakistan. Talks appear to be at a *stalemate and a force reduction is unlikely in the short term, but possible concessions to the TTP in the long term could benefit ISPP and other Salafi-jihadi groups. ISPP and ISKP could take advantage of a decrease in security forces in the northwest to develop stronger interlinkages and resource sharing. ISPP could then use the northwest as a support zone to launch more attacks further south and east. A troop reduction could also provide al Qaeda core and al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent—al Qaeda’s South Asia affiliate—with more options for safe havens. Islamic State and al Qaeda affiliates in other theaters have exploited force drawdowns and reduced counterterrorism pressure to secure havens and launch more cross-border attacks. ISPP and ISKP could attempt to do the same in Pakistan.

[i] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS and TTP Issue Competing Claims of Credit for Killing Policeman in Rawalpindi,” January 31, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.