Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.

October 29 Briefing

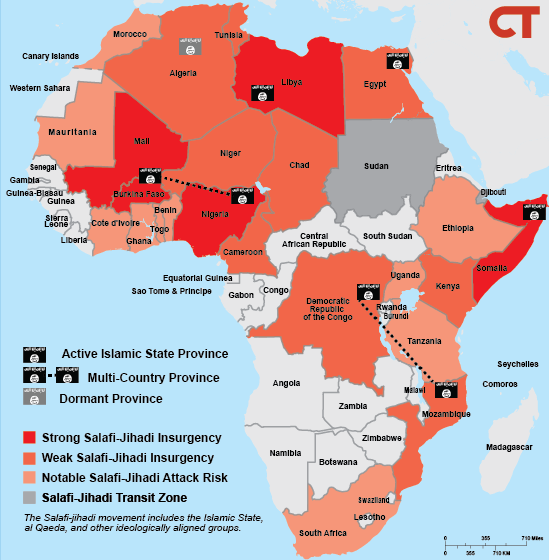

US forces killed Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State’s so-called caliphate, in northwestern Syria on October 26. Baghdadi’s death strikes a serious, but not decisive, blow to his group. The Islamic State has a global organization that includes footholds across Africa, especially in regions facing instability, conflict, and poor governance.

The Islamic State is not defeated in Africa because the conditions that enabled its rise remain (Figure 1). The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes the Islamic State, al Qaeda, and other ideologically aligned groups and individuals, draws strength not from controlling terrain but from establishing relationships with populations made vulnerable by governance failures and violence. These conditions are spreading in Africa and, if allowed to fester and escalate, will allow the Salafi-jihadi movement to strengthen.

- North Africa: Islamic State supporters this month planned a major attack in Morocco, which has largely been spared major Salafi-jihadi attacks since the early 2000s. The group retains a foothold in Libya, its historical hub in Africa. Counterterrorism efforts have degraded the Islamic State in Libya since 2016, but the country’s ongoing civil war is generating popular grievances and security vacuums that allow the group to reorganize and increase recruitment. The Islamic State is also sustaining a low-level insurgency in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. The group has lost much of its ability to attack in Algeria and Tunisia—except for unsophisticated individual attacks—but is positioned to exploit mass political instability in those countries should it arise.

- West Africa: The Salafi-jihadi movement, including an Islamic State affiliate, is spreading rapidly in the western Sahel region, where ethnic and resource conflicts have escalated and states have weakened in recent years. The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate has established a proto-state in northeastern Nigeria.

- East Africa: The Islamic State has a foothold in northern Somalia and may have recently attempted to attack neighboring Ethiopia, which faces rising ethnic violence that Salafi-jihadi groups may exploit. The conflict in Somalia is stalemated but will evolve in favor of Salafi-jihadi groups as governance falters and regional peacekeeping forces draw down.

- Central and Southeastern Africa: The Islamic State is expanding its footprint by recognizing extant armed groups in the northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and northern Mozambique.

[Read a recent assessment of the Islamic State’s global organization from the Institute for the Study of War.]

Figure 1. Islamic State Provinces and Salafi-Jihadi Insurgencies in Africa: October 2019

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute

Read Further On:

At a Glance: The Salafi-Jihadi Threat in Africa

Updated October 29, 2019

Global counterterrorism efforts are rapidly receding with the end of counter–Islamic State operations in Syria and the withdrawal of US troops in October 2019. This withdrawal sets conditions for the return of the Islamic State, even as the organization recovers from the death of its leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and other senior officials in US operations in late October. The US withdrawal has also damaged America’s reputation with current and potential counterterrorism partners wary of suffering the same fate as the abandoned Syrian Kurdish forces. The US administration also seeks to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan, a course that will likely be delayed rather than altered by the breakdown of talks with the Taliban. However, the Salafi-jihadi movement continues to make gains in Africa, including in areas in which previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement is positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations. The return of African Salafi-jihadis from prisons in Syria will likely accelerate these trends.

The Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, on the counteroffensive in Libya, and stalemated in Mali, Somalia, and Nigeria. However, conditions in the last three countries favor the Salafi-jihadi movement rather than its opponents over the next 12–18 months.

Libya’s civil war, reignited on a large scale in April, will continue to fuel the Salafi-jihadi comeback for at least the next several months, possibly allowing the Islamic State or al Qaeda to regain some of the territory they controlled before major operations against them from 2016 to 2019. The Islamic State’s comeback in Libya is part of its global effort to reconstitute capabilities after military defeats, an effort that the group’s late leader, Baghdadi, sought to galvanize in a September audio message. Stalemates in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is rapidly eroding, and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in the eyes of their people.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great power competition, a move also intended to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness — such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown.

The Salafi-jihadi movement currently has four main centers of activity in Africa: Libya, Mali and its environs, the Horn of Africa, and the Lake Chad Basin. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other place is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse. Local crises are the incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the bases for future attacks against the US and its allies.

West Africa

Mali and Burkina Faso

The Salafi-jihadi movement is expanding more rapidly in the western Sahel than in any other African region as communal violence and state fragility spread. The movement’s epicenter in this region is Mali. Salafi-jihadi groups are active in the country’s north and have spread into the country’s center, where ethnic-based violence has increased in the past two years. Neighboring Burkina Faso is destabilizing rapidly as Salafi-jihadi groups take root in its north and east. Several Salafi-jihadi factions are cooperating, particularly in the Mali–Burkina Faso border area, to drive out security forces and establish themselves as the de facto governing power. The violence is causing a humanitarian crisis that has included retaliatory massacres of civilians in central Mali and mass displacement in Burkina Faso.

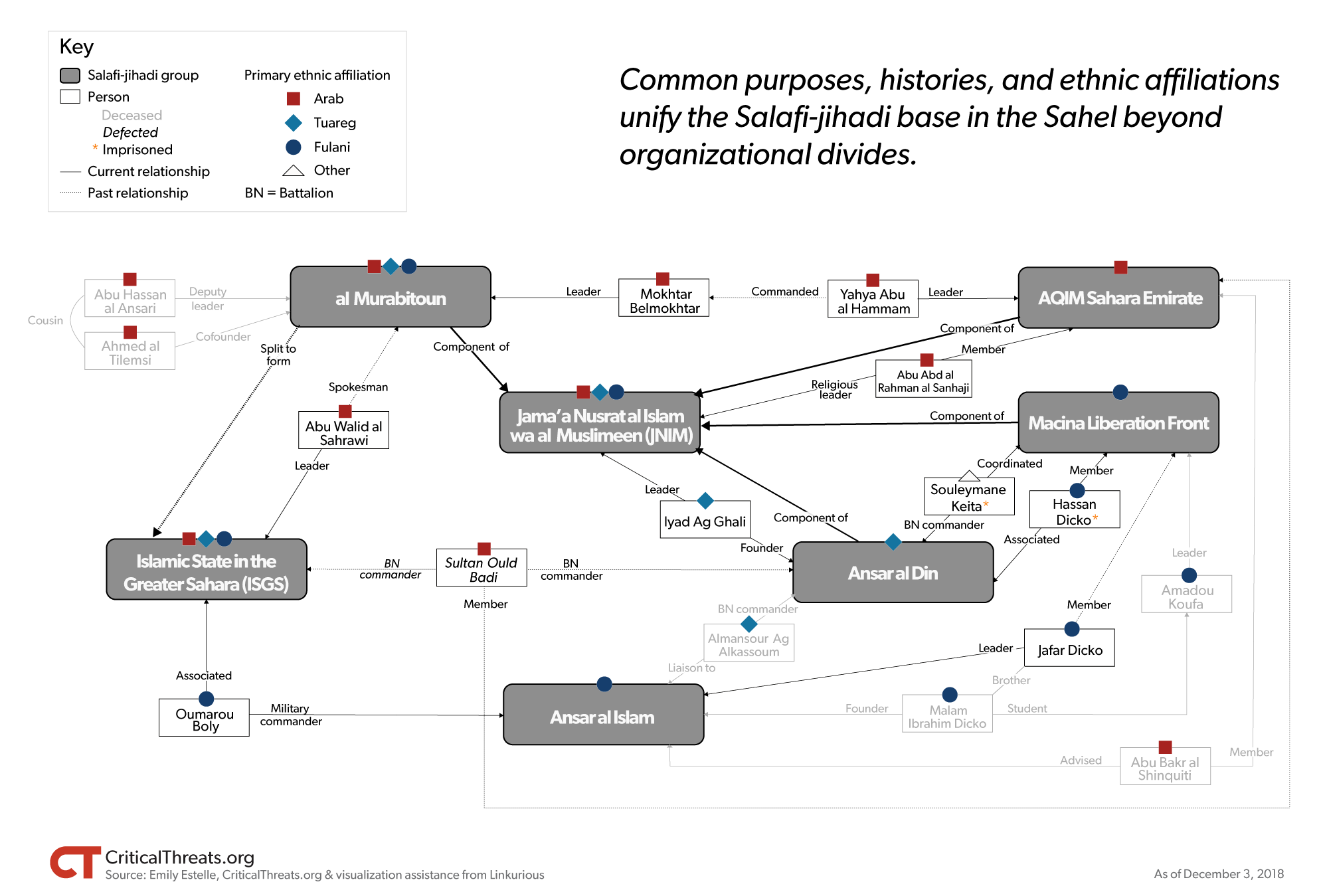

A Salafi-jihadi group in central Mali negotiated a local cease-fire to establish itself as a more effective alternative to the Malian state. The Macina Liberation Front (MLF), a component of AQIM’s Sahelian affiliate Jama’a Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), has stoked ethnic violence between the Fulani and Dogon in central Mali’s Mopti Region in recent years. The MLF and its leader, charismatic preacher Amadou Koufa, seek to delegitimize the state and present the MLF as the Fulani community’s defender. Koufa announced a cease-fire with the Dogon ethnic militia Dan Na Ambassagou in early October, outlining conditions that include ending hostilities toward the Fulani and accepting the MLF’s jurisprudence. Dogon leaders and the MLF reportedly reached an agreement in late October, and Dogon leaders have since demonstrated goodwill toward the Fulani.

The MLF has also increased proselytization in an attempt to win over new followers and demonstrate the Malian government’s inability to respond. MLF members toured mosques in villages in the Koulikoro region, north of the capital Bamako region, and in Mopti. MLF preachers claimed to espouse Islam’s “true values” and tapped into anti-colonial and anti-Western narratives.

Koufa is an important player in the Salafi-jihadi base in the Sahel, which unifies Salafi-jihadi group members and supporters across organizational divides. Koufa mentored the founder of the Burkinabe Salafi-jihadi group Ansar al Islam, for example, and participated in the merger to form JNIM in March 2017. His ability to mobilize local grievances, particularly around Fulani ethnic identity, has enabled the MLF to become the most active JNIM faction. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. The Salafi-Jihadi Base in the Sahel

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute

Competition between JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) for fighters in Mali has caused intergroup friction but will not disrupt de-confliction and occasional cooperation between the groups. ISGS leaders reportedly banned its fighters from listening to Koufa’s audio recordings to prevent defections. The ban followed the defection of an ISGS commander and his brigade to JNIM in mid-2019. Personality-driven leadership disputes have defined the fracturing of Sahelian Salafi-jihadi groups in the past. ISGS emir Abu Walid al Sahraoui initially split from AQIM in 2011 and participated in a series of mergers and splinters leading to his pledge of allegiance to the late Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi in 2016. ISGS has weathered the defection of other brigade leaders in the past.

Meanwhile, Salafi-jihadi groups continue to degrade security and increase their freedom of movement in rural areas of northern Burkina Faso. An attack on October 26 killed 15 civilians in Pobe-Mengao and forced civilians to flee to the Soum Province capital, Djibo, exacerbating an already widespread displacement crisis. [For more on Salafi-jihadi lines of effort in northern Burkina Faso, see the October 16 Africa File.]

Forecast: Salafi-jihadi groups will continue to take control of populations in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso, where they may establish de facto governance and ultimately a proto-state. Militants will target military positions and infrastructure in the Malian-Burkinabe border region to increase their freedom of movement there. The MLF will increase its presence in the Koulikoro region but will avoid encroaching rapidly on the capital to avoid generating a Malian government response that would disrupt its governance project. (Updated October 29, 2019)

North Africa

Morocco

An Islamic State cell planned an attack in Morocco’s capital city and may have intended to establish an Islamic State wilayat (province) in the country. Moroccan authorities disrupted a cell that was planning a bombing at the Casablanca port in late October. Members of the cell had recorded pledges to the late Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and promised to found a branch of the group called “Wilayat Islamic Maghreb.” The cell’s leader had previously attempted to join the Islamic State affiliate in the Sahel. The leader of the cell was in contact with Islamic State members on social media and may have met with a Syrian Islamic State emissary who provided logistical support.

The Islamic State has not conducted a major attack inside Morocco. Since 2015, Moroccan authorities have regularly disrupted cells of would-be Islamic State attackers. The first Islamic State–inspired killing in Morocco occurred in December 2018. The murderers of two Scandinavian tourists pledged allegiance to Baghdadi, but the Islamic State neither claimed nor promoted the attack.

Libya

The protracted battle for Tripoli, Libya’s capital, is degrading security across Libya. The Libyan National Army (LNA) militia coalition, led by Khalifa Haftar, launched an offensive to seize Tripoli in April 2019 and has yet to breach the city’s defenses, even with significant support from Russia, the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. Haftar’s campaign, whether it succeeds or fails, will benefit the Salafi-jihadi movement in Libya. The civil war has destabilized parts of Libya where Salafi-jihadi militants are active, notably the far southwest. The Islamic State and AQIM have havens and access to smuggling and trafficking routes in this region and have attempted to recruit from local populations.

The Islamic State’s increased recruitment in recent months necessitated a series of US airstrikes to curtail the threat in the past month. Even if Haftar succeeds, his methods—including an overly broad definition of who is a terrorist—will fuel a long-term Salafi-jihadi insurgency.

The UN-backed peace process in Libya remains stalled. Plans for a conference in Germany to resume this process have been delayed. The US is actively sustaining its partnerships with the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) on the economy, development, and counterterrorism, but these are stopgap measures without a credible effort to end the civil war. The GNA now faces popular backlash from a teacher strike as it attempts to curb bloated public spending.

Russia is exploiting the absence of a cohesive American and European policy on Libya to push for the conflict’s resolution in a way that secures Russian interests. Russia helped bankroll Haftar’s Tripoli offensive and has since increased military support in an attempt to break the stalemate. Russian officials have simultaneously sustained ties with the GNA, whose officials participated in the Kremlin’s high-profile Africa summit in Sochi this month. Russia’s interests in Libya include acquiring military basing or expanding access to Mediterranean naval facilities, casting itself as a peacemaker and alternative to the West, drawing neighboring Egypt away from the US, reactivating Qaddafi-era economic deals and securing new ones, and securing influence over hydrocarbon resources that in turn increase its leverage over Europe. [For more on Russia’s campaign in Libya and in Africa more broadly, see the October 16 Africa File.]

Forecast: The UN-led peace process in Libya is unlikely to succeed as Libyan factions and their foreign backers remain committed to military campaigns to secure their objectives. Russia will raise its profile as a potential broker and may attempt to facilitate a negotiated end to the conflict that secures its interests, particularly if Haftar’s offensive remains stalled. Separately, the Islamic State may attempt an attack in the coming weeks to prove its continued strength but will otherwise reduce its activity for several months while recovering from US strikes’ effects. The Islamic State will continue its recruitment efforts in southwestern Libya. (Last updated October 16, 2019)

Tunisia

In the past several years, Counterterrorism operations have limited the ability of Salafi-jihadi groups to conduct attacks in Tunisia. For example, militants failed to conduct attacks during two rounds of voting in Tunisia’s presidential elections in September and October despite threats. Grievances that feed Salafi-jihadi recruitment persist, however, and the potential for instability that could galvanize the Salafi-jihadi movement remains. Tunisia faces serious economic problems that its nascent democratic government has struggled to address.

Tunisian security forces continued to attrite the leadership of AQIM’s Tunisian affiliate. This attrition has limited the group’s ability to conduct offensive operations in the past several years. Tunisian forces killed Murad al Chayeb, a leader of the Uqba ibn Nafa’a Brigade, in Kasserine governorate in western Tunisia on October 20. The group’s activity is largely defensive and focused on securing its haven in western Tunisia. It may still be attempting offensive operations, however. A Tunisian operation that killed three senior militants on September 2 may have disrupted a planned attack coinciding with the start of the presidential election season.

Forecast: Leadership losses will prevent AQIM’s Tunisian affiliate from conducting an offensive attack without widespread instability in Tunisia. Islamic State cells in Tunisia will attempt attacks and are more likely to succeed, but any attack will likely be unsophisticated. (Updated on October 29, 2019)

Algeria

Algerian legal professionals are striking to protest the executive’s interference in the judiciary in the lead-up to December elections. The Algerian justice ministry reshuffled half the country’s judges and prosecutors earlier in October, in a move seen as an attempt to shape magistrates’ oversight of the upcoming elections.

The political situation in Algeria has been deadlocked since protests began in February and led to the ouster of longtime President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April. Military and political leaders are advancing plans for December elections to resolve the ongoing political crisis. Protesters and political opposition have resisted the army’s push for quick elections, which they fear will solidify the army’s current power.

Forecast: The political deadlock in Algeria is unsustainable and will reach a turning point in the coming months. Elections will likely occur and establish a puppet government while the military retains control. The elections will not resolve the legitimacy crisis and may lead to violent unrest, particularly if security forces crack down more aggressively on protesters and detain more protest leaders. These are potential flashpoints that could lead to violence between protesters and security forces, setting conditions for a full military takeover or an insurgency. (Updated September 17, 2019)

East Africa

Somalia

Al Qaeda’s affiliate in East Africa, al Shabaab, is waging an insurgency in Somalia that threatens neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia. A stalemate is eroding in al Shabaab’s favor as African Union peacekeeping forces draw down ahead of their scheduled withdrawal in 2021. Al Shabaab seeks to expand its insurgency into Kenya and Ethiopia, in part as punishment for their participation in the peacekeeping mission. The group also seeks to radicalize Muslim communities in Kenya and Ethiopia. Al Shabaab frequently attacks security forces in eastern Kenya and has conducted multiple high-profile attacks on soft targets in the country since 2013. Al Shabaab also recently plotted attacks in Ethiopia and may be seeking to increase its operations there. [For more on the Salafi-jihadi threat to Ethiopia, read the October 1 Africa File.]

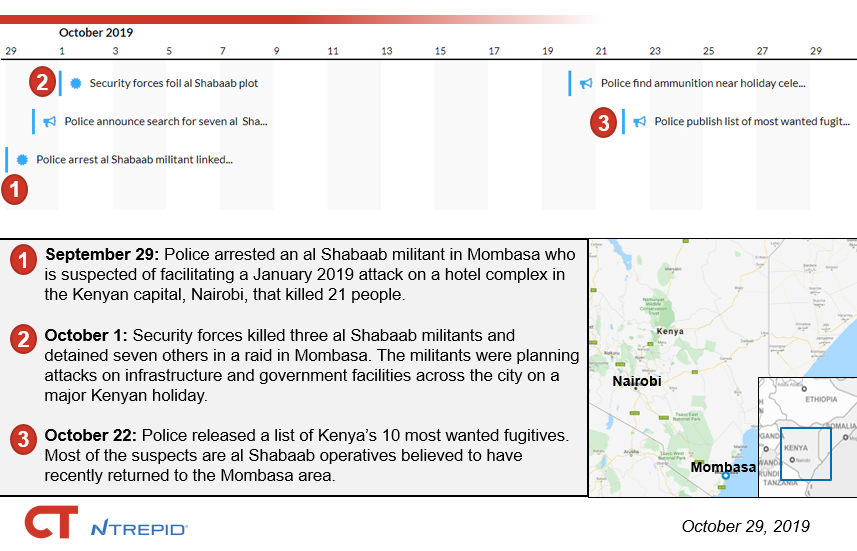

Al Shabaab is beginning to use Mombasa, a major Kenyan port, as an operations hub. Mombasa-based cells have attempted multiple attacks in recent weeks. (See Figure 3.) Al Shabaab recruits from Mombasa but has plotted few attacks there since a Kenyan crackdown in 2014. Police prevented what would have been one of al Shabaab’s largest-ever attacks in Mombasa in early October. A recent Kenyan most wanted list indicates that al Shabaab operational planners come from coastal Kenyan communities rather than Kenya’s ethnic Somali areas, indicating that non-Somalis in al Shabaab are taking on a larger role in attack planning. [For more on al Shabaab’s recent plot in Mombasa, read the October 16 Africa File.]

Forecast: Al Shabaab will attempt another high-profile attack along the Kenyan coast within the next 12 months and will activate cells for smaller, more frequent attacks in the area. Al Shabaab will continue recruiting from the coast while simultaneously expanding its recruitment among Muslim-minority communities in Kenya’s interior. (Updated October 28, 2019)

Figure 3. Kenyan Security Forces Pursue al Shabaab Cells in Mombasa

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute

Several al Qaeda organs praised recent al Shabaab attacks in media, signaling ongoing messaging coordination. Al Shabaab, al Qaeda General Command, and al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula each released statements about al Shabaab attacks on a US base and an Italian convoy in Somalia on October 1. The al Qaeda General Command statement also called for retaliation against the US for the recent deployment of US forces to Saudi Arabia. Al Shabaab’s attacks on Western positions in Somalia serve the global Salafi-jihadi movement’s broader goal to expel Western forces from Muslim lands. [For more on al Shabaab’s October 1 attack on US and Italian forces in Somalia, read the October 1 Africa File.]

Ethiopia

Africa’s second most populous country, Ethiopia, faces mounting instability. A turbulent political transition is exacerbating the ethnic strife that gives Ethiopia one of the world’s largest populations of internally displaced people and creates opportunities for the Salafi-jihadi movement to spread. The country’s security sector is fragmenting. Elections and the 2020 census could trigger a wider conflict. Increasing geopolitical competition in the Horn of Africa risks compounding Ethiopia’s instability.

Deadly protests in Ethiopia reflect growing divisions within Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s base and could lead to broader destabilization. The core of Abiy’s base is the Muslim-majority Oromo community. Abiy has struggled to appease Oromo hard-liners and youth, risking his legitimacy. Protests broke out after a prominent Oromo Abiy critic accused police of attempting to arrest him. Between October 23 and 27, 67 people died in protests and ethnic clashes in south-central Ethiopia and the capital Addis Ababa. Oromo youth may become increasingly susceptible to recruitment by Salafi-jihadi groups if they lose faith in the state.

Forecast: Ethiopia will experience increasing levels of ethnic violence over the next 12 months as ethnonationalist parties stoke tensions ahead of a contentious census and elections in 2020. Hard-line Oromo rebels, some of whom are likely already engaged in low-level militant activity, will increase attacks against minorities in the Oromia region, further polarizing the Oromo community. (As of October 28,2019 )

Ethiopia threatened Egypt with war over a Nile dam dispute. Ethiopia and Egypt are deadlocked over the construction of Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which Egypt fears will threaten its water supply. Egypt has previously considered military strikes to prevent the dam’s construction, and Ethiopia has accused Cairo of being behind a foiled attack against the dam in 2017. Abiy entered office in 2018 intent on peacefully resolving the dispute but has become more bellicose in recent weeks. Abiy claimed that Ethiopia is prepared to go to war over the dam on October 22 while stressing that a diplomatic resolution is preferable.

Russia is attempting to mediate the dispute to increase its influence in the Horn of Africa. Russian President Vladimir Putin separately met with Abiy and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al Sisi on the sidelines of the first-ever Russia-Africa summit in Sochi, Russia, on October 24–25. Putin offered to mediate the dispute, possibly to counter a US mediation offer that Egypt accepted on October 23. Sisi and Abiy agreed to resume talks during the Sochi summit, but neither has formally responded to Putin’s offer.

Putin has strong ties with Sisi and seeks to develop Russia’s relationship with Ethiopia, which is one of the world’s fastest growing economies and a former Soviet client state. Ethiopia recently signed a nuclear energy cooperation agreement with Russia. Abiy also agreed to purchase a Russian air-defense system during the Sochi summit, possibly to deter Egypt from attacking the dam.

Forecast: Egypt will attempt to sabotage the dam’s construction, possibly by sponsoring attacks against the dam by Ethiopian rebel groups. Egypt and Ethiopia will attempt to sway Sudan by competing for influence within its new regime, further destabilizing the country’s fragile transition. (Updated October 28, 2019)

Mozambique

Salafi-jihadi militants have waged an insurgency in northern Mozambique since 2017. Some of these militants operate under the banner of a new Islamic State affiliate in Central Africa that also claims attacks by an Islamist rebel group in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Mozambican security forces are pursuing a heavy-handed response to the insurgency that will exacerbate local populations’ grievances against the state, likely driving more support to the militants.

Disputed elections may destabilize Mozambique and provide opportunities for Salafi-jihadi militants to expand their insurgency. A disputed presidential poll may lead to the collapse of an August peace agreement between the guerrilla-movement-turned-opposition-party Renamo and the ruling Frelimo party. Renamo rejected incumbent Filipe Nyusi’s victory in the October 15 poll, accussing Frelimo of fraud, violence, and intimidation. Renamo officials had threatened to fight in the event of a disputed election.

Forecast: Renamo elements will begin a low-level insurgency in the next three months that will divert Mozambican security resources away from efforts to combat Salafi-jihadi militants in the country’s north.