Africa File, December 12, 2024: Kremlin Pivot to Libya or Sudan Post-Syria; Turkey Mediates Ethiopia-Somalia Deal

December 12, 2024

Africa File, December 12, 2024: Kremlin Pivot to Libya or Sudan Post-Syria; Turkey Mediates Ethiopia-Somalia Deal

Data Cutoff: December 12, 2024, at 10 a.m.

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here. Follow CTP on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook.

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways:

- Russia. Russia has maintained the security of its Syrian bases in the short term but expressed long-term uncertainty about the future of these bases, the loss of which would undermine Russia’s ability to project power into the Mediterranean and support Russian military logistics in Africa. Russia is preparing to move some assets out of Syria, although Russia has not made any moves that signal that a complete withdrawal from Syria is imminent. Russia will likely turn to Libya to mitigate its reliance on or replace the role of its Syrian bases in the Mediterranean and Africa, but the Kremlin faces political obstacles that make Russia’s long-term position in Libya vulnerable. Russia may increase the small but already growing role of Port Sudan in its logistic network and strategic power projection objectives, although the Kremlin also faces political vulnerabilities in war-torn Sudan. The Kremlin’s failure to reinforce the Bashar al Assad regime damages the global perception of Russia as an effective partner, which could undermine the Kremlin’s partnerships with African autocrats and its economic, military, and political influence in Africa.

- Somalia. The SFG and Ethiopia agreed to work toward granting Ethiopia access to the Red Sea on December 11, after Turkish-mediated talks. This agreement will likely lead Ethiopia to withdraw from its controversial naval port agreement with Somaliland and decrease the possibility of a direct or proxy conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia. Ethiopia’s withdrawal from the Somaliland agreement would likely lead the Somali Federal Government (SFG) to reverse its decision to expel Ethiopian troops from Somalia and exclude Ethiopian troops from the new African Union mission in Somalia, which will begin in 2025. Ethiopia and Somalia’s rapprochement may quicken the end of an ongoing dispute between the SFG and the Jubbaland state government in southern Somalia by leading Ethiopia to cut alleged military support for Jubbaland and freeing the SFG’s military and political bandwidth to address the dispute. The SFG and Jubbaland may engage in further clashes in the following weeks, although the fighting will likely remain limited.

Russia

Russia has maintained the security of its Syrian bases in the short term but expressed long-term uncertainty about the future of these bases, the loss of which would undermine Russia’s ability to project power into the Mediterranean and support Russian military logistics in Africa. The Kremlin newswire Tass reported on December 8 that “Syrian opposition leaders guaranteed the security of Russian military bases and diplomatic institutions in Syria.”[1] An unspecified Syrian source told Tass on December 9 that Syrian opposition forces do not intend to capture the Russian bases and that both bases are functioning normally.[2]

Figure 1. Reported Control of Terrain in Syria

Source: Institute for the Study of War; Critical Threats Project.

The Kremlin is working to negotiate a long-term solution for the bases with the Syrian transitional authorities. Bloomberg reported on December 12 that Russia was “nearing an agreement” with the transitional authorities and believed it already had an “informal” agreement to allow Russia to keep its air base in Hmeimim and naval base at Tartus.[3] Kremlin Spokesperson Dmitry Peskov stated on December 9 that the Kremlin will host “serious discussions” with the future Syrian authorities about its two Syrian bases at an unspecified future date.[4] Russian officials and affiliated media outlets quickly softened their characterization of Syrian rebels from “terrorists” to “opposition” to set conditions for dialogue as the Bashar al Assad regime’s imminent fall became obvious, on December 8.[5]

The Kremlin has expressed uncertainty about the stability of any potential deals with the new Syrian transitional authorities, however. Peskov noted on December 9 that it is too early to discuss future plans for these bases since such a discussion involves “those who will lead Syria” and on December 10 that it is “difficult to predict” what will happen in Syria.[6] Russian state outlet RBC reported on December 9 that the Syrian National Coordination Committee’s foreign relations head Ahmed al Asrawi stated that Syria would continue to uphold agreements that are in Syria’s interest and “never” take a hostile position toward Russia or any other friendly country.[7]

The loss of its bases in Syria would undermine Russia’s strategic ambition to project power into the Mediterranean. Tartus is Russia’s only formal overseas naval base, and Russia uses it to project power into the Mediterranean for various purposes. Russia built up its presence in Tartus before its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 to counter, deter, and monitor any NATO operations in the Mediterranean, particularly aircraft carriers, among other things.[8] The base also linked Russia’s Black Sea assets to the Mediterranean, although the closure of the Turkish Straits has severed this link for the duration of the Russian war in Ukraine.[9]

The loss of Russia’s footprint in Syria would immediately interrupt Russia’s Africa Corps rotations and resupply efforts in Africa. Russia’s bases in Syria are hubs for shipments from Russia intended for Libya and eventually sub-Saharan Africa.[10] Syrian bases would presumably serve a similar purpose if Russia ever secured its long sought-after base in Sudan.

Figure 2. Africa Corps Logistics Network in Africa

Source: Liam Karr; Grey Dynamics; Jules Duhamel; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Russia is preparing to move some assets out of Syria, although Russia has not made any moves that signal that a complete withdrawal from Syria is imminent. The Russian Baltic Fleet’s Alexander Shabalin Project 775 large landing ship exited the Baltic Sea maritime zone on December 10, and the Institute for the Study of War assesses that this ship may relocate some Russian military assets from Tartus.[11] Satellite imagery taken on December 9 and 10 shows that all Russian ships and submarines have left the Port of Tartus.[12] Ukraine’s Main Military Intelligence Directorate reported on December 10 that Russian forces are still disassembling and removing troops, weapons, and equipment from Hmeimim Air Base in An-124 and Il-76 military transport aircraft and are “dismantling” equipment at Tartus under the supervision of Russian Spetsnaz.[13] The reported drawdown at Hmeimim Air Base follows earlier reports on December 6 that the Russian military redeployed some of its air defense assets previously positioned at the base.[14] Open-source analyst MT Anderson and ISW reported that four of Russia’s six ships previously stationed at Tartus are in a holding pattern roughly five miles west of the Port of Tartus.[15]

ISW assesses that Russia’s posture in Syria suggests that the Kremlin is still waiting to decide on a path forward as events in Syria continue to unfold. ISW has assessed that the Kremlin is “very likely hesitant to completely evacuate all military assets from Syria in the event that it can establish a relationship with Syrian opposition forces and the transitional government and continue to ensure the security of its basing and personnel in Syria.”[16] The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace senior fellow Dara Massicot assessed that a full Russian withdrawal from Syria would involve the Russian Mediterranean flotilla sailing around Europe to the Baltic Sea due to Turkey’s closure of the Turkish straits under the Montreux Convention and a massive Russian airlift with hundreds of cargo sorties from Hmeimim and Tartus.[17]

Russia will likely turn to Libya to mitigate its reliance on or replace its Syrian bases for its military logistics and objectives to project power into the Mediterranean. Libya is crucially the only country with a Russian military presence in Africa that Russian cargo planes can directly reach from Russia without refueling.[18] Heavier cargo planes can reach Libya only by flying over Turkish airspace.[19] This range issue will increase the political leverage that Turkey will hold over Russia or the practical costs of supporting Russian operations in Africa if more cargo planes stop to refuel at other airfields.

The Kremlin had already increased Libya’s role as an operational hub for its various Africa Corps deployments in sub-Saharan Africa throughout 2024. Russia sent at least 1,000 soldiers and 6,000 tons of equipment to Libya via Syria in March and April 2024.[20] Africa Corps then deployed some of these soldiers and equipment to sub-Saharan countries.[21] Russia refurbished several bases in Libya in 2024 to accommodate Russian cargo planes and expand the storage capacities of the bases.[22]

Russia’s newly upgraded military facilities in Libya could handle some Russian logistics traffic that previously went through Syria. Wagner Group–linked sources told the French magazine Jeune Afrique on December 9 that Russia could expand its use of airports near Benghazi.[23] This report presumably refers to al Khadim Air Base, which is roughly 60 miles east of Benghazi. The Telegraph reported that Russia significantly renovated three other air bases in 2024—al Qardabiyah and al Jufra in central Libya and Brak al Shati in southwestern Libya.[24] These upgrades included renovations to the airstrips to expand runways and enable Il-76 cargo planes to land. All three bases are 200–400 miles farther away from Russia, however, which means that planes would have to carry less cargo to be in range for direct flights.

These renovations are presumably part of the upgrades that the Kremlin promised to Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar in 2023 in exchange for permanent Russian docking rights at Tobruk.[25] Haftar and the Kremlin have not announced any formal agreement, but a Russian naval base at Tobruk would help offset the negative logistics and strategic impact of Russia’s loss of Tartus. The Polish Institute of International Affairs assessed in May 2024 that Russia may already have begun to upgrade infrastructure at Tobruk for a future naval base.[26] The Wall Street Journal reported in September 2023 that Russian officials claimed that Tobruk was already able to support Russian refueling, resupply, and repair of their naval vessels.[27] Bloomberg reported in November 2023 that the port is currently insufficient for permanent basing use, however.[28]

Figure 3. Africa Corps Network in Libya

Source: Liam Karr.

The Kremlin faces political obstacles that make Russia’s long-term position in Libya vulnerable, however. Russia’s precarious position in Libya is dependent on Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar, since Russia lacks any formal historical agreement with Libya.[29] Libya’s frozen civil war currently prevents Russia from reaching a more solid agreement with a unified government. This fact essentially makes any Russian basing in Libya vulnerable to the same fate as its Syria bases if Haftar’s regime collapsed.

Major players such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the United States may obstruct Russia in Libya. The UAE is Haftar’s main patron and would presumably need to at least tacitly allow Haftar to agree to a Russian naval base. The United States has increased outreach to Haftar in recent years and pressed him to reduce his ties with Russia.[30] US officials have specifically warned Haftar against accepting a Russian naval base as part of these discussions.[31] US activity incentivizes Haftar to hedge his partnership with Russia to avoid retaliation from the United States.

Russia may increase the small but already growing role of Port Sudan in Russia’s logistic network and strategic power projection objectives. The Kremlin has increased support for the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) since April 2024 in exchange for promises to revive a stalled 2017 deal for a Red Sea naval base that would host up to 300 Russian service members and four ships.[32] The assistant SAF commander-in-chief claimed in late May 2024 that Sudan and Russia would soon sign a series of military and economic agreements to finalize the exchange.[33] Sudanese media reported in August that the sides are still finalizing aspects of the deal related to the conditions of the base and Russian provision of fighter jets, however.[34]

Russia has long pursued a Red Sea port to protect its economic interests in the region and improve its military posture vis-à-vis the West in the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean.[35] Russian media have reported that a base in Sudan would serve primarily as a resupply and stopover hub to enable Tartus to transition from a resupply base to a multipurpose naval base, a goal Russia has previously outlined as a key element of its effort to bolster its Mediterranean power projection.[36] The loss of Tartus would eliminate this broader benefit and require that Port Sudan replace Tartus as a resupply base. The Royal United Services Institute assessed that a naval base in Sudan would also help position Russia as a bulwark against perceived maritime security threats in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean and serve as a local logistics hub for its activity in Sudan.[37]

Russia has likely already started to incorporate its limited capacity in Port Sudan into its logistics network. US-sanctioned and Wagner-linked Russian military cargo airline Avicaon Zitotrans has sent several Il-76TD cargo flights from Russia to Port Sudan since August.[38] Some of these flights then went on to Mali.[39] A Kremlin-linked milblogger included Port Sudan on a map of Africa Corps logistics across Africa.[40] The milblogger notably omitted an air route between Russia and Sudan, however. This omission suggests that Russian planes cannot or do not regularly travel directly between Russia and Port Sudan.

The Kremlin faces political vulnerabilities in Sudan like those it faces in Libya, a fact that limits Russia’s ability to quickly scale up its activity in Sudan to replace Syria in the short term. Sudan is in the middle of a civil war and lacks a unified government that can promptly push ahead with negotiations or offer long-term guarantees. This conflict has already undermined Russia’s basing plans in previous years as various military and transitional governments constantly renegotiated the deal, while governmental change paused any implementation.[41] Russia’s original plans aimed to build on the preexisting naval infrastructure at Port Sudan, and it is unclear whether Port Sudan is currently capable of basing Russian naval vessels.[42]

The United States and others are pressuring Sudanese leaders to reject any Russian naval base agreement. US officials warned Sudan’s military rulers against accepting a Russian naval base in 2022 before the outbreak of the civil war in 2023.[43] SAF officials have notably rejected Iranian overtures for a naval base to avoid alienating its historical allies—Egypt and Saudi Arabia—as well as Western countries.[44]

Russia’s failure to reinforce the Assad regime damages the global perception of Russia as an effective partner, which could politically undermine the Kremlin’s partnerships with African autocrats and its economic, military, and political influence in Africa. Syria has served as the blueprint for the Russian “regime survival package.”[45] Russia offers military and population control support to keep autocrats in power and economic and political cover in the international system to shield them from international pressure as part of this “package.”[46] Russia expands its military footprint and increases its economic and political hold over target governments as a result. This influence translates into partner support for Russia’s broader aims to create a Russian-led multipolar world, bolsters Russia’s status as a superpower, and gives the Kremlin preferential economic access in partner countries.[47]

Russia has offered this regime-protection package to several African allies. Such partners include the central Sahelian juntas that face an existential threat from local al Qaeda– and Islamic State–affiliated insurgencies. None of these juntas have commented on the collapse of the Assad regime.

Figure 4. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), could draw parallels or inspiration from Syria and increase pressure on the juntas and Russia. JNIM publicly congratulated its “brothers in Syria” twice in December.[48] Their most recent statement expresses hope that the people of “all Muslim countries” will experience the joy of the people of Syria and Sudan. This rhetoric frames Syria as an example or desired end-state for JNIM. JNIM attacked the Malian capital for the first time in nearly a decade in September.[49] The attackers notably targeted an air base that houses Africa Corps personnel during the attack. JNIM also attacked the suburbs of the Nigerien capital, Niamey, in October and is slowly encircling Burkina Faso’s capital.[50] A JNIM spokesperson gave a speech in November before the Syrian rebel offensive that warned that JNIM had entered the “second stage” of its jihad and would soon capture city centers.[51] CTP and others have assessed for over a year that JNIM and the Islamic State Sahel Province are capable of attacking and overrunning major population centers across the Sahel but have decided not to do so in favor of siege-like tactics.[52]

The Sahelian regimes and other Russian partners could alternatively view the Assad regime’s collapse as an indictment of the Assad regime, not of Russia as a partner, and not seek to change their approach to the Kremlin. The juntas have all capitalized on popular anti-French and anti-colonial sentiment and promised to fix faltering Western-backed counterterrorism strategies. This political strategy has helped them capitalize on decades-long grievances and local fears of the Salafi-jihadi insurgency to bolster their popular support. The Salafi-jihadi insurgency in the Sahel also has an ethnic layer that differs from the Assad regime’s sectarian minority rule in Syria. The Sahelian insurgents are associated with minority ethnic groups at the geographic and political periphery of the Sahel states because the insurgent groups have historically exploited grievances among these ethnic communities to recruit militants. This trend adds a dimension of ethnically-based fear and loyalty to the junta’s base among the majority ethnic groups at the geographic and political core of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.

The relative popularity of the Sahelian regimes compared to the Assad regime, and to their respective military opponents, makes the Sahelian regimes less vulnerable to rapid collapse than the Assad regime was. Syrian rebels toppled the Assad regime in less than a week as regime forces melted away due to more than a decade of dysfunction that hollowed out the regime and the collapse of the Iranian-backed Axis of Resistance forces that had bolstered it as a result of Hezbollah’s defeat.[53] The Sahelian juntas have had less time to damage their popularity, state apparatuses, and militaries, and they are not dependent on third-party ground forces for survival, as Assad was. These comparative advantages almost certainly mean that an insurgent offensive to topple the Sahelian juntas would be more costly and take longer. A more capable partner and longer timeline would give Russia more ability, incentive, and time to reinforce the juntas than the one week Russia had to bolster collapsing Assad regime forces.

Somalia

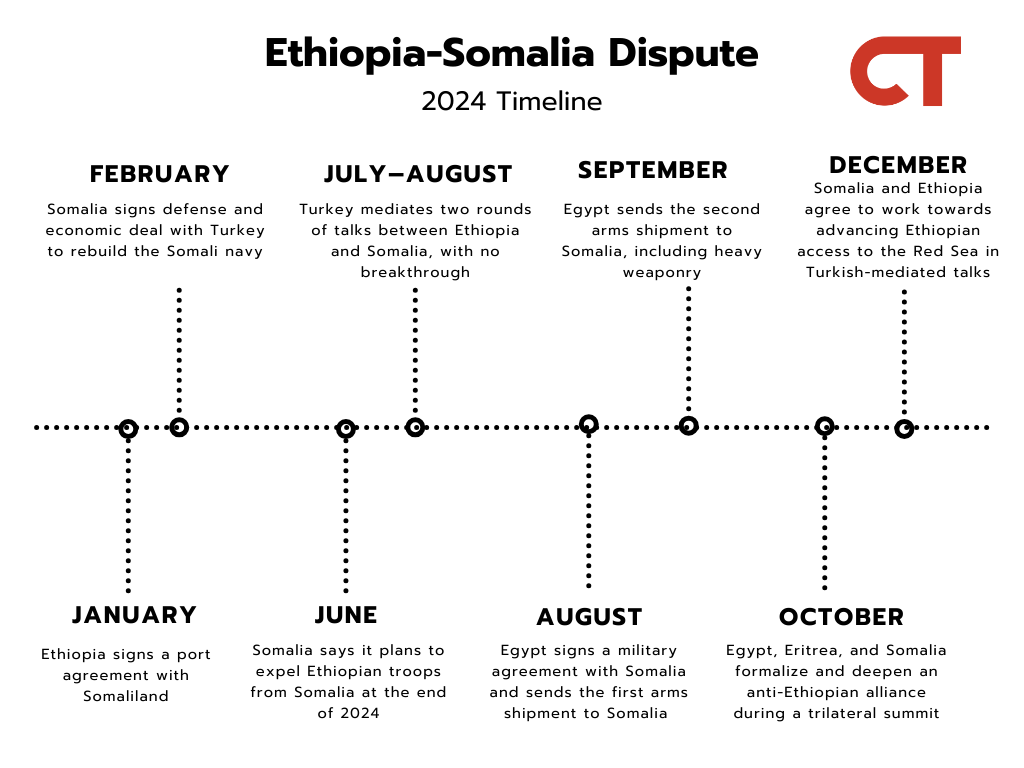

The SFG and Ethiopia agreed to work toward granting Ethiopia access to the Red Sea on December 11, after Turkish-mediated talks. This agreement will likely lead Ethiopia to withdraw from its controversial naval port agreement with Somaliland and decrease the possibility of a direct or proxy conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia. Ethiopia and Somalia reached the deal after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan held separate talks between Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud in Ankara on December 11.[54] Erdoğan expressed optimism that the agreement would eventually ensure Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea.[55] Abiy and Mohamud said that both sides are ready to cooperate and implied that the discussions addressed the nearly yearlong political dispute between Ethiopia and Somalia over the Ethiopia’s naval base agreement with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region.[56]

Ethiopia and Somalia have been in a political conflict since Ethiopia signed a naval port deal with in January 2024.[57] The agreement granted Ethiopia land in Somaliland for a naval base on the Red Sea in return for Ethiopia’s recognition of Somaliland’s independence.[58] The Somali Federal Government (SFG) rejected the deal as illegal—as it considers Somaliland to be part of its territory—and called for the withdrawal of Ethiopian forces from the country.[59] Ethiopia has approximately 10,000 troops deployed in Somalia as part of the African Union (AU) Mission in Somalia and through other bilateral agreements to fight al Qaeda’s Somali affiliate, al Shabaab.[60]

Figure 5. Somalia-Ethiopia Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

Turkey has sought to mediate the dispute at least in part because of its significant economic and defense ties to both Ethiopia and Somalia.[61] Turkey previously mediated two rounds of talks between Ethiopia’s and Somalia’s foreign ministers in July and August 2024.[62] Turkey has been a major defense partner in Somalia since the early 2010s and signed an economic and defense deal in February 2024 to reconstruct the Somali Navy and defend against “any external violations or threats” to Somalia’s coast in the interim in exchange for 30 percent of the revenue from the Somali’s offshore exclusive economic zone.[63] Turkey is the second-largest foreign investor in Ethiopia, with an estimated $2.5 billion in projects in the country at the end of 2021.[64] Turkey also sent Bayraktar TB2 drones to Ethiopia to help turn the tides against Ethiopian rebels between 2021 and 2022.[65]

Ethiopia will likely pull out from the Somaliland deal as a result of its new agreement with the SFG. This revocation would decrease the risk of a proxy or direct conflict between Ethiopia and the SFG. The Turkish-mediated agreement does not directly address the Somaliland deal, but Somalia would presumably not agree to a deal that includes recognizing Somaliland’s independence, which Somalia has repeatedly rejected as a violation of its territorial integrity.[66] Somali officials said that Ethiopia retracted its agreement with Somaliland as part of the talks.[67] The December 11 agreement stipulated that in February 2025, Ethiopia and Somalia will hold “technical talks” for four months, respect Somalia’s territorial integrity, and recognize “potential benefits” of Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea.[68]

Ethiopia’s withdrawal from the Somaliland agreement would likely lead the SFG to reverse its decision to expel Ethiopian troops from Somalia and to exclude Ethiopian troops from the new AU mission in Somalia, which will begin in 2025, a reversal that will decrease tensions and the risk of a clash between Ethiopia and the SFG. Somali officials said in June that the Somali government expects all Ethiopian forces to withdraw from Somalia by the end of 2024 if Ethiopia follows through on its port deal with Somaliland.[69] Ethiopia likely intended to keep soldiers in Somalia regardless of the SFG’s demands so that Ethiopia could counter al Shabaab and create a buffer zone to prevent future cross-border incursions by al Shabaab or Egyptian forces that have deployed to Somalia in 2024.[70] Ethiopia remaining in Somalia past the SFG deadline would have provided a pretext for the SFG to attack Ethiopian forces on Somali territory.

It is unclear how the December 11 agreement and subsequent agreements between Ethiopia and Somalia will impact Somalia’s growing military cooperation with Egypt. Somalia increased its military cooperation with Egypt and signed deals with Egypt in August for Egyptian troops to replace Ethiopian forces in Somalia, ostensibly to combat al Shabaab.[71] Egypt aimed to threaten Ethiopia over a political dispute related to Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, while the SFG wanted to retaliate against and counter Ethiopia’s agreement with Somaliland.[72] Ethiopia views Egypt’s growing military presence on its border as a national security risk and has warned against Egyptian military participation in the new AU mission.[73]

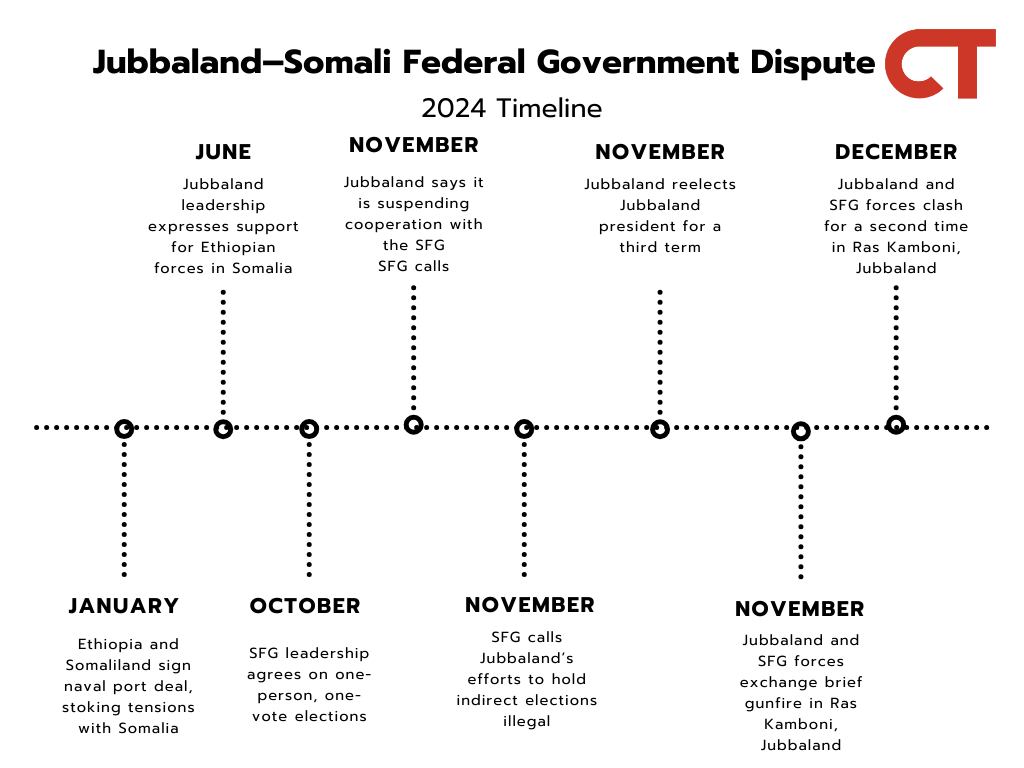

Ethiopia’s and Somalia’s rapprochement may quicken the end of an ongoing dispute between the SFG and the Jubbaland state government in southern Somalia by leading Ethiopia to cut alleged military support for Jubbaland and freeing the SFG’s military and political bandwidth to address the dispute. Jubbaland forces claimed to capture Ras Kamboni, a town in Jubbaland near the border with Kenya, on December 11 after fighting with the Somali National Army (SNA) that Jubbaland security officials said ended in the surrender of dozens of SFG forces.[74] Jubbaland and SNA troops had already exchanged gunfire when the SFG initially deployed troops to Ras Kamboni, on November 25.[75] The conflict stems from a political dispute between Jubbaland and the SFG over the format of Somali elections that began in October 2024.[76] The SFG said that the purpose of the November deployment was to fight al Shabaab, but the proximity in time to Jubbaland state elections on November 25 indicates that it was in response to these disputed elections.[77]

The Somali government said on December 7 that Ethiopia sent two commercial planes loaded with weapons to Kismayo, Jubbaland’s capital, to support Jubbaland forces and undermine the SFG.[78] CTP could not verify any flight tracking information that indicates these flights occurred. The SFG added that the planes carried Jubbaland officials back to Ethiopia to “organize conspiracies” against the SFG.[79] Somali media and local journalists released pictures and videos on December 5 and 6 that show Ethiopian troops, tanks, and other armored vehicles along the Somali-Ethiopia border.[80] The SFG said on December 6 that Ethiopian troops tried to cross the border into Gedo region, Jubbaland, but that Somali forces prevented them.[81] Jubbaland’s security minister denied on December 7 that Ethiopia delivered weapons to Jubbaland.[82]

The SFG and Jubbaland may engage in further clashes in the following weeks, although fighting will likely remain limited. A Jubbaland security minister said that the SFG attacked Jubbaland forces with drones on December 11, which would indicate an escalation in the types of weapons used in previous clashes in November.[83] The fighting also reportedly expanded outside of Ras Kamboni. A federal army officer in Mogadishu said that the fighting on December 11 was in an area 20 km from Ras Kamboni.[84]

The SFG ordered the withdrawal of all SNA forces from Lower Juba, where Ras Kamboni is located, on December 11, presumably to reduce the risk of an expansion of violence.[85] External involvement helped stalemate a similar conflict in 2020. The strong Ethiopian presence in the disputed region of Jubbaland in 2020 dissuaded Jubbaland and its Kenyan backers from expanding violence into the disputed region as long as they maintained control over the state government.[86] Meanwhile, the SFG and Ethiopia, who were partners at the time, were content with their de facto control over the disputed region and preferred freezing the conflict to angering Kenya.[87]

Figure 6. Jubbaland–Somali Federal Government Dispute Timeline

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

[1] https://tass dot ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/22612661

[2] https://tass dot ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/22615165

[3] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-12/russia-nears-deal-with-new-syria-leaders-to-keep-military-bases

[4] https://www.rbc dot ru/politics/09/12/2024/6756b99f9a79476d4303e372; https://t.me/tass_agency/289916

[5] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-8-2024; https://meduza dot io/en/feature/2024/12/09/from-terrorists-and-militants-to-opposition-and-new-authorities

[6] https://t.me/tass_agency/289916; https://t.me/ne_rybar/3717; https://t.me/tass_agency/290151; https://t.me/tass_agency/290154

[7] https://www.rbc dot ru/rbcfreenews/675706c29a794738298d1f35

[8] https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/12/first-sign-russian-navy-evacuating-naval-vessels-from-tartus-syria

[9] https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/march/turkey-montreux-convention-and-russian-navy-transits-turkish

[10] https://www.voanews.com/a/middle-east_russia-expands-military-facilities-syria/6205742.html; https://alleyesonwagner.org/2024/05/10/mediterranean-sea-objective-for-the-african-corps; https://www.svoboda.org/a/gotovitsya-boljshaya-zavarushka-voennaya-ekspansiya-rossii-v-livii/32939757.html; https://verstka.media/rossiya-naraschivaet-voennoe-prisutstvie-v-livii; https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[11] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-10-2024; https://x.com/Drox_Maritime/status/1866471867005255976; https://x.com/OAlexanderDK/status/1866507293958774830

[12] https://x.com/kromark/status/1866154120257671340; https://x.com/MT_Anderson/status/1866124525647143118

[13] https://t.me/DIUkraine/4989

[14] https://x.com/Mitch_Ulrich/status/1865093121723281496; https://x.com/Mitch_Ulrich/status/1865093374853648408; https://t.me/milinfolive/136887

[15] https://x.com/MT_Anderson/status/1866155694593810766; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-9-2024

[16] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-10-2024

[17] https://x.com/MassDara/status/1865854264980935160

[19] https://x.com/JohnLechner1/status/1865778183057932326

[20] https://alleyesonwagner.org/2024/05/10/mediterranean-sea-objective-for-the-african-corps; https://www.svoboda.org/a/gotovitsya-boljshaya-zavarushka-voennaya-ekspansiya-rossii-v-livii/32939757.html; https://verstka.media/rossiya-naraschivaet-voennoe-prisutstvie-v-livii

[21] https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf; https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/05/10/la-russie-accroit-sa-presence-en-libye-au-grand-desarroi-des-occidentaux_6232547_3212.html

[22] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2024/12/03/russia-expands-military-presence-libya-pictures

[23] https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1638941/politique/russie-afrique-les-consequences-de-la-chute-dassad-pour-le-continent

[24] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2024/12/03/russia-expands-military-presence-libya-pictures

[25] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-05/putin-s-move-to-secure-libya-bases-is-new-regional-worry-for-us

[26] https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[27] https://www.wsj.com/world/africa/russia-seeks-to-expand-naval-presence-in-the-mediterranean-b8da4db

[28] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-05/putin-s-move-to-secure-libya-bases-is-new-regional-worry-for-us; https://meduza.io/en/news/2023/11/05/bloomberg-russia-s-plans-to-establish-military-bases-in-libya-spark-concern-in-u-s-over-potential-to-spy-on-all-of-e-u; https://www.pism.pl/webroot/upload/files/Raport/PISM%20Report%20Africa%20Corps_.pdf

[29] https://www.theafricareport.com/370967/explainer-why-assads-fall-in-syria-may-limit-russias-operations-in-africa

[30] https://www.wsj.com/world/africa/russia-seeks-to-expand-naval-presence-in-the-mediterranean-b8da4db; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-05/putin-s-move-to-secure-libya-bases-is-new-regional-worry-for-us

[31] https://x.com/JohnLechner1/status/1865104497657208886

[32] https://sudantribune.com/article285164; https://jamestown.org/program/will-khartoums-appeal-putin-arms-protection-bring-russian-naval-bases-red-sea; https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/15/russia-sudan-putin-east-africa-port-red-sea-naval-base-scuttled; https://jamestown.org/program/russia-in-the-red-sea-converging-wars-obstruct-russian-plans-for-naval-port-in-sudan-part-three

[33] https://sudantribune.com/article286105; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-26/sudan-s-army-deepens-ties-with-russia-iran-as-civil-war-rages

[34] https://sudantribune.com/article288335

[35] https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russias-port-sudan-naval-base-power-play-red-sea; https://gulfif.org/slow-but-persistent-russias-overseas-basing-strategy-in-the-red-sea-and-the-gulf-of-aden; https://www.institute.global/insights/geopolitics-and-security/security-soft-power-and-regime-support-spheres-russian-influence-africa#conclusion-and-recommendations

[36] https://www.mk dot ru/politics/2020/11/12/poyavlenie-rossiyskoy-voennoy-bazy-v-sudane-obyasnil-ekspert.html; https://tass dot com/defense/1222673

[37] https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russias-port-sudan-naval-base-power-play-red-sea

[38] https://www.ft.com/content/e581fc02-ef80-4a00-bdf1-1be4b5e0a916; https://x.com/fabsenbln/status/1822682179794600236; https://x.com/fabsenbln/status/1828770577613836335; https://x.com/MenchOsint/status/1844406862923563177; https://x.com/MenchOsint/status/1843704035020550168

[39] https://www.ft.com/content/e581fc02-ef80-4a00-bdf1-1be4b5e0a916; https://x.com/fabsenbln/status/1822682179794600236; https://x.com/fabsenbln/status/1828770577613836335

[40] https://x.com/casusbellii/status/1866133045671010798

[41] https://jamestown.org/program/russia-in-the-red-sea-converging-wars-obstruct-russian-plans-for-naval-port-in-sudan-part-three

[42] https://jamestown.org/program/russia-in-the-red-sea-converging-wars-obstruct-russian-plans-for-naval-port-in-sudan-part-three

[43] https://sudantribune.com/article264733

[44] https://www.wsj.com/world/middle-east/iran-tried-to-persuade-sudan-to-allow-naval-base-on-its-red-sea-coast-77ca3922; https://sudantribune.com/article288335

[45] https://static.rusi.org/SR-Russian-Unconventional-Weapons-final-web.pdf

[46] https://static.rusi.org/SR-Russian-Unconventional-Weapons-final-web.pdf

[47] https://static.rusi.org/SR-Russian-Unconventional-Weapons-final-web.pdf; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-special-edition-russian-diplomatic-blitz-advances-the-kremlins-strategic-aims-in-africa

[48] SITE Intelligence Group, “In Joint Statement Celebrating Syrian Conquest, AQIM and JNIM Warn Militants to Maintain Readiness to Confront Foreign Enemies,” December 9, 2024, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com

[49] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce8d996x1r0o

[50] https://www.theafricareport.com/366430/al-qaeda-affiliate-jnim-claims-attack-near-niamey; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-areas-of-operation-in-the-sahel

[51] https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1861478375694454964; https://x.com/lsiafrica/status/1861436414971216252

[52] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-june-27-2024-niger-reallocates-uranium-mine-is-strengthens-in-the-sahel-au-future-in-somalia#Sahel; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-september-19-2024-jnim-strikes-bamako-hungary-enters-the-sahel-ethiopia-somalia-proxy-risks#Mali; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-november-7-2024-niamey-threatened-boko-haram-fallout-in-chad-m23-marches-on-eastern-drc-somalia-jubbaland-tensions#Niger; https://www.institutmontaigne.org/expressions/effondrement-securitaire-au-mali-et-au-burkina-faso-que-peut-il-se-passer-anticiper-la-crise-travers

[53] https://www.msnbc.com/opinion/msnbc-opinion/syrias-assad-hts-russia-iran-united-states-rcna183478; https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/05/syria-assad-regime-collapsing-quickly

[54] https://x.com/HarunMaruf/status/1866956708297179388; https://www.reuters.com/world/erdogan-meets-somalia-ethiopia-leaders-separately-amid-somaliland-dispute-2024-12-11

[55] https://www.barrons.com/news/turkey-says-ethiopia-somalia-reach-compromise-deal-to-end-feud-51034d60

[56] https://www.barrons.com/news/turkey-says-ethiopia-somalia-reach-compromise-deal-to-end-feud-51034d60

[57] https://warontherocks.com/2024/01/a-port-deal-puts-the-horn-of-africa-on-the-brink

[58] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalias-cabinet-calls-emergency-meet-ethiopia-somaliland-port-deal-2024-01-02

[59] https://www.voanews.com/a/somalia-insists-ethiopia-not-be-part-of-new-au-mission-/7858887.html; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalia-expel-ethiopian-troops-unless-somaliland-port-deal-scrapped-official-2024-06-03; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalia-accuses-ethiopian-troops-illegal-incursion-2024-06-24

[60] https://ecfr.eu/article/threes-a-crowd-why-egypts-and-somalias-row-with-ethiopia-can-embolden-al-shabaab/

[61] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-special-edition-external-meddling-for-the-red-sea-exacerbates-conflicts-in-the-horn-of-africa#Somalia

[62] https://www.reuters.com/world/turkey-mediating-somalia-ethiopia-talks-port-deal-officials-2024-07-01/; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/second-round-somalia-ethiopia-talks-turkey-ends-with-no-deal-progress-made-2024-08-13

[63] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/turkeysource/turkey-signed-two-major-deals-with-somalia-will-it-be-able-to-implement-them

[64] https://www.theafricareport.com/141761/ethiopia-turkey-ankaras-ongoing-economic-and-military-support; https://www.aa dot com.tr/en/africa/turkey-eyeing-more-investments-in-ethiopia-envoy/2144828

[65] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/20/world/africa/drones-ethiopia-war-turkey-emirates.html; https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/20/world/africa/drones-ethiopia-war-turkey-emirates.html; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/exclusive-us-concerned-over-turkeys-drone-sales-conflict-hit-ethiopia-2021-12-22

[66] https://x.com/HarunMaruf/status/1866956708297179388; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalias-cabinet-calls-emergency-meet-ethiopia-somaliland-port-deal-2024-01-02/; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalia-expel-ethiopian-troops-unless-somaliland-port-deal-scrapped-official-2024-06-03

[67] https://x.com/TomGardner18/status/1867114091816550709

[68] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/12/11/turkey-somalia-ethiopia-joint-declaration/3a2759fa-b80f-11ef-8afa-452ab71fe261_story.html

[69] https://www.voanews.com/a/somalia-wants-all-ethiopian-troops-to-leave-by-december/7641135.html; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalia-expel-ethiopian-troops-unless-somaliland-port-deal-scrapped-official-2024-06-03

[70] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-december-5-2024-french-influence-in-africa-erodes-further-syrias-impact-on-russia-in-africa-and-the-mediterranean-somalia-political-dispute-turns-hot-drc-rwanda-peace-plans#Somalia

[71] https://www.voanews.com/a/somalia-insists-ethiopia-not-be-part-of-new-au-mission-/7858887.html; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalia-expel-ethiopian-troops-unless-somaliland-port-deal-scrapped-official-2024-06-03/; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalia-accuses-ethiopian-troops-illegal-incursion-2024-06-24; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-september-5-2024-egypt-ethiopia-and-somalia-conflict-looms-is-gains-in-niger-russia-aids-burkina-fasos-nuclear-energy-push#Horn

[72] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-special-edition-external-meddling-for-the-red-sea-exacerbates-conflicts-in-the-horn-of-africa#Somalia

[73] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-special-edition-external-meddling-for-the-red-sea-exacerbates-conflicts-in-the-horn-of-africa

[74] https://garoweonline dot com/en/news/somalia/somalia-sna-soldiers-lose-raskamboni-battle-to-jubaland-troops-surrender-to-kdf; https://x.com/HarunMaruf/status/1866760959949201695; https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/12/11/somalia-federal-forces-jubbaland-fighting/b28610a4-b7e1-11ef-8afa-452ab71fe261_story.html

[75] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somali-leaders-face-reciprocal-arrest-warrants-over-disputed-regional-election-2024-11-28/; https://www.garoweonline dot com/en/news/somalia/somalia-jubaland-forces-clash-with-sna-forces-after-madobe-takeover; https://x.com/RAbdiAnalyst/status/1861403825304744190

[76] https://acleddata.com/2024/10/28/controversy-over-electoral-reform-sparks-debate-in-somalia-amid-al-shabaab-operation-october-2024

[77] https://www.garoweonline dot com/en/news/somalia/somalia-elite-troops-deployed-to-jubaland-as-madobe-wins-3rd-term-in-office; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalias-jubbaland-government-suspends-ties-with-federal-administration-2024-11-28

[78] https://x.com/SONNALIVE/status/1865749563136467323

[79] https://x.com/SONNALIVE/status/1865749563136467323

[80] https://www.garoweonline dot com/en/news/somalia/ethiopian-troops-move-deep-into-somalia-amid-tension; https://x.com/Tuuryare_Africa/status/1864805785638691150; https://x.com/Tuuryare_Africa/status/1865095236583592142

[81] https://x.com/SONNALIVE/status/1865001695140299192; https://www.hiiraan dot com/news4/2024/Dec/199245/somali_forces_prevent_ethiopian_troop_advance_in_gedo.aspx

[82] https://hiiraan dot com/news4/2024/Dec/199279/jubbaland_denies_federal_government_s_accusations_over_ethiopian_weapons_in_kismayo.aspx

[83] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/fighting-erupts-between-somalias-jubbaland-region-federal-government-officials-2024-12-11

[84] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/fighting-erupts-between-somalias-jubbaland-region-federal-government-officials-2024-12-11

[85] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/fighting-erupts-between-somalias-jubbaland-region-federal-government-officials-2024-12-11

[86] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/b158-ending-dangerous-standoff-southern-somalia