Al Shabaab After Kismayo

October 03, 2012

Al Shabaab After Kismayo

Al Qaeda’s affiliates across Africa – Somalia’s al Shabaab, Nigeria’s Boko Haram, and al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb – have apparently been increasingly seeking to coordinate their efforts.[1] The United States would face an al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist network that stretches across Africa if those efforts succeed. Al Shabaab has suffered major setbacks over the past year, including the September 28 loss of a major stronghold in the southern Somali port city of Kismayo, but the group has not been defeated. The fall of Kismayo could herald the collapse of the group’s quasi-state, but it may also serve to strengthen more radical factions within the terrorist group that prefer to focus on regional and global jihad. It will also strain the weak alliance of regional states and local groups, such as Kenya, Ethiopia, and their proxies, whose unifying interest has been the fight against al Shabaab and not a long-term vision for Somalia, over which they disagree. The fight against al Shabaab is not over in Somalia and now is not the time to declare victory; instead, now is the time to ensure that recent achievements last.

Al Shabaab’s quasi-state in southern and central Somalia has been progressively reduced over the past thirteen months. Last August, the group suddenly vacated Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital, announcing a tactical shift from holding ground to guerrilla-type warfare.[2] Ugandan and Burundian peacekeeping troops in Mogadishu, operating under the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) mandate, secured their newly-gained positions in Mogadishu and continued to push outward against al Shabaab. Kenya, increasingly concerned by al Shabaab’s reach from Somalia south into its own territory, launched Operation Linda Nchi in October 2011.[3] That operation led Ethiopia to deploy forces into the major population centers in central Somalia and along its borders as well. By spring 2012, Kenyan troops were being incorporated into AMISOM, and planning was in place to capture Kismayo.

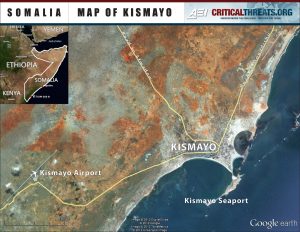

Operation Sledge Hammer, the AMISOM-led offensive to take Kismayo, began early the morning of September 28 with an amphibious landing on beaches just north of the city.[4] Increasing military activity preceded the operation, however.[5] Kenyan warships and airstrikes targeted known al Shabaab positions around the city, including what the Kenyan military described as an “armory” at the Kismayo airport. Kenyan planes also dropped leaflets on September 27 warning civilians to evacuate the city. When Kenyan and Somali government troops advanced on the city the following day, they met little resistance during their approach. Throughout the day, Kenyan jets and helicopters provided air support, targeting al Shabaab positions. Significantly, Kenya claims that airstrikes killed senior al Shabaab officials Sheikh Hassan Yaqub Ali and Sheikh Abdikarim Adow.[6] Al Shabaab withdrew from the city and now the Somali government flag flies over symbolic sites of control, such as the airport.[7]

The fall of Kismayo, which served as al Shabaab’s operational and financial hub, is an important step toward defeating al Shabaab. Al Shabaab had allied with local Islamist militias in August 2008 to seize control of Kismayo and has held it since. Despite the withdrawal, it is not clear that the group has fully relinquished the idea of controlling the area, although it is unlikely that it will be able to re-establish itself there to the same degree as before. Al Shabaab spokesman Ali Mohamed Rage, also known as Ali Dhere, warned, “The enemies have not yet entered the town. Let them enter Kismayo, which will soon turn into a battlefield.”[8] As AMISOM troops moved into Kismayo, an explosion hit one of the administration office buildings, which al Shabaab’s military spokesman Sheikh Abdi Aziz Abu Mus’ab called a portent of what was to come.[9] Indirectly, high-casualty rates among the Kenyan contingent deployed in Kismayo could affect AMISOM’s strength, which rests on troops contributions from regional countries. The Kenyan public may pressure its government to limit or end direct military support for AMISOM. At the moment, however, it appears unlikely that al Shabaab will be more successful in driving AMISOM out of Kismayo than it has been in similar efforts in and around Mogadishu.

The question of who will fill the power vacuum in Kismayo now comes to the fore, however. The alliance between pro-government factions is not strong, and rests primarily on mutual interests in defeating al Shabaab. Interests vary widely and, in many cases, conflict apart from that goal. It is extremely likely that local clan militias will vie for control of the city, a central hub for Somalia’s lucrative charcoal industry, to gain access to its resources. These clan militias receive support from Kenya and Ethiopia. Kenya has supported an Ogadeni militia, whose leaders very likely see this as an opportunity to gain power in Somalia. The Ogadeni clan also constitutes the majority of members of a rebel group in Ethiopia, the Ogaden National Liberation Front. Ethiopia, therefore, might be concerned should the Ogadenis gain power in Somalia. The clans in Kismayo have resisted Ogadeni attempts to control Kismayo in the recent past, choosing instead to support al Shabaab. Conflict over Kismayo does not bode well either for the fight against al Shabaab, which will require continued cooperation between pro-government factions, or for the stabilization of the country.

Al Shabaab as an organization will likely have to adapt after the loss of the city. The fall of Kismayo may intensify divisions within the group’s leadership over whether al Shabaab should pursue a national agenda to establish an Islamic state in Somalia or whether al Shabaab should pursue a regional, or global, agenda of jihad.[10] There is already evidence that al Shabaab leaders focused on establishing an Islamic state in Somalia are beginning to splinter away from the group. Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, formerly a leader of an Islamist militia called Hizb al Islam and now a senior leader in al Shabaab, has publicly distanced himself from some of al Shabaab’s more radical positions over the past year. More recently, rumors have circulated that Hizb al Islam has defected from al Shabaab, though this has been contested.[11] The core leaders who believe in regional and global jihad will be strengthened should these nationalist leaders continue to peel away from the group. Resources that would otherwise be devoted toward financing a local fighting force and governing areas could instead go toward funding terrorist operations. Though the overall strength of the group may be weakened, the resolve of its leaders to pursue regional and global jihad has not been weakened.