Designating the Haqqani Network: New Constraints Moderating Pakistan's Relationship with the U.S.

August 08, 2012

Designating the Haqqani Network: New Constraints Moderating Pakistan's Relationship with the U.S.

Introduction

The Haqqani Network is one of the most violent and dangerous insurgent organizations, and the most prolific user of terrorism, operating in South Asia today. The network maintains complex and diversified funding streams throughout Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Persian Gulf. The U.S. has done little to combat the network’s financial base or cut into its revenue streams, however. The U.S. State Department has yet to list the group as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), a key first step towards actively targeting the group’s international financial activity and support network, despite the group appearing to fit the necessary criteria.

The State Department’s inactivity appears to result at least partly from fears within the U.S. government that designating the Haqqani Network as an FTO will imperil the precarious U.S.-Pakistan relationship and possibly elicit a strong reaction or retaliation from Pakistan. This fear is likely overblown: Pakistan faces a serious, impending financial crisis, the avoidance of which may depend on continuing to improve relations with the U.S. The recently reopened gates of the NATO supply lines are unlikely to be abruptly slammed shut. The list of possible Pakistani reactions to such a move is limited. The constraints on Pakistan’s actions are emblematic of a larger change in the factors governing the U.S.-Pakistan relationship, which now include Pakistan’s teetering economy, upcoming election, and the increased importance of domestic political consideration for Pakistani leaders.

The Haqqanis

The Pakistan-based Haqqani Network is the most virulent enemy group active in Afghanistan. It has historically had close ties to al Qaeda and other regional terrorist and insurgent groups, such as the Quetta Shura Taliban, Pakistani Taliban, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), and others.[1] The group is responsible for some of the worst violence inside Afghanistan, including multiple complex and spectacular attacks in Kabul, attacks on the U.S. embassy and the headquarters of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in September 2011 and April 2012, and the bombing of an American base in Wardak in 2012 that injured 77 U.S. troops.[2]

The group maintains its traditional power center in Paktia, Paktika and Khost provinces of Afghanistan but is based out of North Waziristan agency in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas. In North Waziristan, the Haqqani Network has built itself a safe haven where it is able to plan and prepare for attacks, rest and refit, and coordinate with allied and likeminded insurgent and terrorist groups.[3]

The group also manages a vast network of diversified businesses and financial ventures that gives it deep pockets with which to carry out operations in Afghanistan. The network relies on both licit and illicit forms of revenue: on the illicit side, extortion, smuggling networks, kidnapping and racketeering are widespread; on the licit side, the Haqqanis are engaged in running construction companies and car dealerships among other ventures, many of which are believed to be linked to the Pakistani military’s own expansive business establishment.[4] The group also raises large amounts of money in the form of donations from wealthy individuals in Gulf Arab countries.[5]

The Supposed Pitfalls of Designation

To date, the State Department has not designated the Haqqani Network as an FTO, despite repeated calls from lawmakers and military commanders, and numerous pieces of legislation being introduced urging it to do so.[6] On July 16, Congress passed a bill urging the State Department to declare the network an FTO or to explain why it was refusing to do so.[7] The State Department announced in November 2011 that it was conducting a “final formal review” on whether to label the Haqqani Network as an FTO.[8] It has thus far refused to take any action against the group as a whole, choosing instead to target individual members of the network.[9]

According to Jeffrey Dressler at the Institute for the Study of War, designating the entire network rather than just individual members has big advantages when it comes to tackling its resource streams and degrading its operations.[10] An FTO designation allows U.S. authorities to seize a designee’s property, freeze its bank accounts, and make it illegal to engage in business with it. Individuals can, however, take precautions that would prevent damage being levied upon their network as a whole, for example, by transferring assets in their name to a different member of the organization. Designating the whole network as an FTO would enable the U.S. to target not only every member of the organization and all its assets, but also anybody engaging in business with, affiliated with, or found to be supporting the network.[11] In theory, by targeting facilitators and their international assets and interests, the U.S. would be able to dramatically increase the cost of doing business with the Haqqani Network, both in Afghanistan, and across international borders.

Given that the Haqqani Network appears to fit all the criteria for designation—it is foreign, engages in terrorism, and threatens U.S. nationals or national security—and that doing so would give the U.S. strong tools with which to take on the group, why has the State Department dawdled on designation for so long?[12] According to Dressler, opponents of designation fear endangering U.S. peace negotiations with the Taliban and eliciting a negative reaction from Pakistan, which the U.S. accuses of being the Haqqani Network’s primary sponsor.[13] They further tout that labeling the Haqqani Network as an FTO will put the U.S. in the awkward position of being forced to designate Pakistan, with which it is heavily engaged, as a state sponsor of terrorism.[14]

A Rocky Past for U.S.-Pakistan Relations

The fear that Pakistan will react strongly to such a designation is colored by the turbulent recent history of U.S.-Pakistan relations. Those fears do not, however, take into account changed ground realities and domestic pressures inside Pakistan that will likely work to constrain such a reaction.

Relations between the U.S. and Pakistan have suffered dramatically over the past year and a half. The breakdown started with the killing of two Pakistanis in Lahore by a CIA contractor in February 2011. This incident was exacerbated by the May 2011 raid that killed Osama bin Laden deep inside Pakistan and embarrassed the Pakistani government. The relationship reached its nadir in November 2011 when, following a botched border raid in which U.S. forces killed 24 Pakistani soldiers, Pakistan closed NATO supply lines through the country to Afghanistan for over seven months. The supply route closure forced the U.S. to move the majority of its Afghanistan-bound traffic through vastly more expensive air routes and ground routes through Russia and Central Asia.[15] The Pakistani routes were recently reopened following protracted and painstaking negotiations between the U.S. and Pakistan.[16]

Those who worry about a Pakistani reaction fear that Pakistan may retaliate by once again closing the supply routes through the country, or engineering causes for backlogs, delays, and other roadblocks to NATO traffic. An additional worry is that Pakistan may encourage the Haqqani Network to launch increased and deadlier attacks upon U.S. troops inside Afghanistan.

The Dire State of Pakistan’s Economy

The idea that Pakistan could take its anger out on the U.S. by utilizing its most readily available form of leverage—control over NATO supply routes to Afghanistan—fails to recognize that the Pakistanis have their own reasons for not wanting to scuttle the recent supply routes deal and the accompanying improvement in bilateral relations. Pakistan’s economy is growing more fragile by the day and is soon to be subject to extraordinary external pressures. These pressures forced the Pakistanis to essentially capitulate in the supply routes contest in the hope that a deal would help restart stalled aid flows from the U.S., which are vital to ensuring the Pakistani economy does not go into freefall this year.[17]

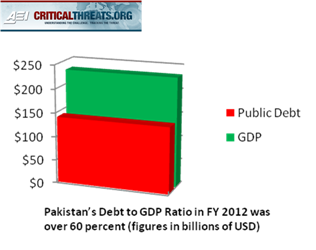

|

While the above figures are indicative of Pakistan’s generally unhealthy economy, the reasons for its precarious political position today come from more immediate economic pressures. In 2008, amid the prospects of catastrophic economic failure, Pakistan went to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout package that exceeded $11 billion, repayable from 2012 through 2015 (in 2011, Pakistan did not receive the last $3 billion tranche of the program because it failed to satisfy IMF fiscal targets governing the release of the final tranche).[24] While the bailout program staved off financial disaster and a default on foreign debt in 2008, Pakistan faces intense economic pressure now that it has to start repaying its loans to the IMF. It paid back over $1.2 billion to the Fund in FY 2012.[25]

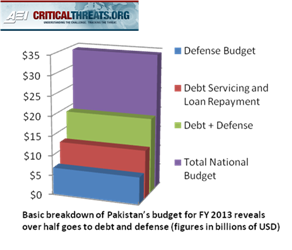

|

It is in this context that Pakistan approached recent negotiations with the U.S. over reopening the NATO supply lines. Pakistan initially took a hard line, demanding an unambiguous apology from the U.S. for the death of its troops, and a hike in fees from $250 to $5,000 for every NATO tanker that transited Pakistan.[30] The U.S. called Pakistan’s bluff, however. The U.S. refused to accede to what it saw as Pakistani rent-seeking and began expanding its use of alternative supply routes to Pakistan, accepting the greatly increased cost of the indirect transport route. The U.S. also withheld over $1.2 billion in military aid to Pakistan under the Coalition Support Funds (CSF) program.[31]

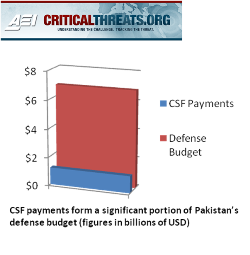

Pakistan likely realized that its supply blockade was not having the intended effect on the U.S., and once financial deadlines started to loom in the U.S. and Pakistan, its conditions began to soften and evaporate. Pakistan settled for a “soft” apology from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and dropped its request for increased truck fees. The U.S., for its part, agreed to expedite the release of the stalled $1.2 billion under the CSF program.[32]

Two separate ticking clocks likely forced Pakistan’s hand in the supply route negotiations: the maturing IMF loans due in 2013 and the end of the U.S. fiscal year FY 2012 on October 1, 2012. At the end of FY 2012, unspent money appropriated for that year can no longer be disbursed. If Pakistan waited any longer, it would have risked losing the outstanding $1.2 billion as well as any further CSF reimbursements it could claim for costs incurred after May 2011 when it stopped submitting receipts to the U.S. as part of its protest against the bin Laden raid.[33] Pakistan has thus far submitted over $600 million for the period after May 2011, and the new bills could run into the billions (though the U.S. typically only approves about 60 percent of the amount Pakistan bills).[34]

|

Limited Options for Retaliation

Given its precarious economic footing, Pakistan is unlikely to jeopardize its financial lifeline by reclosing supply routes any time soon. Indeed, the aid sword continues to dangle hazardously overhead for Pakistan. On July 20, the U.S. Congress voted to cut $650 million in aid to Pakistan as part of its defense appropriations bill, the latest in a number of bills threatening to strip Pakistan of aid it had been authorized.[38] While that number is likely to change based on the way the House and Senate share appropriations responsibilities, the message is probably not lost on the Pakistanis that they have few friends left in Washington, D.C. and that aid from the U.S. is no longer the sure thing it used to be. Furthermore, Pakistan recognizes the importance of needing to improve relations with the U.S.; if it does need to go back to the IMF to seek readjustment of its current loans, or additional bailout funding, the IMF would be unlikely to cooperate in the face of strong U.S. opposition.

The Pakistani military, which has a history of intervening in the name of national interest during particularly dire domestic situations, appears to be at a loss for how to rectify Pakistan’s economic ship. The military has largely watched from the sidelines, allowing the civilian government to take ownership of the crisis lest it be tarred by the same brush when time comes to assign responsibility for the country’s economic failures. The civilian government is well aware that it is going to be seen as responsible for the country’s economic fortunes. Given that this is an election year in Pakistan, the government will likely not let the military easily bully it into closing off supply routes or undertaking steps that will imperil the government’s ability to secure the immediate aid it needs from the U.S. in order to repay its upcoming loans and (somewhat) balance its budget.

The only other significant recourse for Pakistan to display its displeasure at an FTO designation of the Haqqani Network would be for the network’s handlers to encourage it to step up attacks inside Afghanistan against NATO and host-country forces. Then again, the Haqqani Network has never really held back from the fullest application of violence, and an increase in attacks should be expected if the Haqqanis were given an FTO designation regardless of outside encouragement. This scenario assumes that the Pakistani military is even able to exert operational control over the Haqqani Network, which is very much in doubt.[39] While Pakistan’s support to, and benevolent ignorance of, the network has been variously established, the notion that the Haqqanis are bound to obey their Pakistani patrons is much more circumspect.[40]

The idea that the U.S. would be forced to designate Pakistan as a state sponsor of terrorism if the Haqqani Network was labeled as an FTO, furthermore, does not merit serious concern. If the U.S. was compelled to designate Pakistan as such because of its established links to an FTO, such a designation would have been applied long before given Pakistan’s ties to LeT. LeT, the group responsible for the 2008 Mumbai attacks, and with which Pakistan’s intelligence services have maintained a longstanding relationship, has been on the FTO list since 2001.[41] If labeling a group as an FTO compelled the U.S. to label all the group’s affiliates as supporters of terrorism, it would have been forced to designate the Haqqani Network as an FTO years ago due to its relations with al Qaeda, among other FTOs. The fact that the Haqqani Network designation is even being debated right now is indicative of the vast leeway the government enjoys in applying the label. Slapping the FTO brand on the Haqqanis is not for the purposes of making sure that bureaucratic lists are meticulously complete, but to give the U.S. government the necessary powers to actively target some of the group’s foundational interests. The U.S. is not compelled to target the Pakistani state as a whole, but it will gain the ability to take action against individuals within Pakistan who are assisting a terror network in its activities.

Conclusion

There could be several motivations for not designating the Haqqani Network as an FTO. The idea that Pakistan is likely to react in a meaningfully negative manner should not be counted among them. Pakistan is about to pass through a very turbulent economic period and needs all the help it can get from friends, aid donors, and willing international financial institutions, the list of which is shrinking. Pakistan is unlikely to further its international isolation, jeopardize the resumption of much-needed CSF payments, and imperil the diminishing but still salvageable viability of its economy in an effort to express its displeasure over actions the U.S. takes that would be, even to the Pakistanis, entirely logical and predictable.

In fact, given the unique circumstances that currently exist, the inherent restraints on Pakistani retaliation and the recent “upward spiral” in U.S.-Pakistan relations (including potential talks of a joint U.S.-Pakistani offensive against the Haqqani Network), the U.S. government is currently presented with what may be a singular opportunity to designate the Haqqanis as an FTO and escape meaningful repercussions from Pakistan.[42]

Pakistan no longer operates in the context of a pure military dictatorship as it did in days past, when the deals and motivations of powerbrokers were more unified and less complicated. The combination of economic woes, a domestic governance deficit that the military does not want to own and the pressures of electoral politics in an election year have all had a tangible impact on the way Pakistan formulates its foreign policy towards the U.S. and its neighborhood writ large. The simple conclusion that Pakistan will match the U.S. for every seeming slight does not necessarily hold true anymore.

Gretchen Peters, “Crime and Insurgency in the Tribal Areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan,” Combating Terrorism Center, October 15, 2010. Available: http://www.ctc.usma.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Crime-and-Insurgency_Final.pdf

Jeffrey Dressler, “Terror Is Their Family Business,” The Weekly Standard, July 16, 2012. Available: http://www.weeklystandard.com/print/articles/terror-their-family-business_648234.html

Jeffrey Dressler, “Terror Is Their Family Business,” The Weekly Standard, July 16, 2012. Available: http://www.weeklystandard.com/print/articles/terror-their-family-business_648234.html

David Trilling “Northern Distribution Nightmare,” Foreign Policy, December 6, 2011. Available: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/12/06/afghanistan_resupply_nato_ndn

“Eric Schmitt, “Clinton’s ‘Sorry’ to Pakistan Ends Barrier to NATO,” New York Times, July 3, 2012. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/world/asia/pakistan-opens-afghan-routes-to-nato-after-us-apology.html?pagewanted=all

The actual amount of Pakistan’s Foreign Exchange Reserves fluctuates, as of August 2, 2012 it was estimated at over $14.5 billion.

“Pakistan’s forex reserves drop to $14.574 billion” Reuters, August 2, 2012. Available: http://dawn.com/2012/08/02/pakistans-forex-reserves-drop-to-14-574-billion/

“Economic Survey of Pakistan 2011-12: Chapter 8: Trade and Payments,” Pakistan Ministry of Finance. Available: http://www.finance.gov.pk/survey/chapter_12/08-TradeAndPayments.pdf

Bradley Klapper and Rebecca Santana, “Pakistan Opens NATO Supply Lines Into Afghanistan,” Huffington Post, July 3, 2012. Available: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/03/pakistan-nato-supply-lines-_n_1646931.html

“Pakistan receives $ 1.18 bln from US under coalition support fund,” AFP, August 2, 2012. Available: http://dawn.com/2012/08/02/state-bank-receives-1-18-bln-from-us-under-csf/

Mehtab Haider, “US rejects CSF claims of $1.3 bn,” The News, July 18, 2012. Available: http://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-13-16164-US-rejects-CSF-claims-of-$13-bn

Pakistan’s defence budget for FY 2012-13 is approximately $6.8 billion, based on figures from Pakistan’s Ministry of Finance.

“Goodby Haqqani network?” Express Tribune, August 6, 2012. Available: http://tribune.com.pk/story/418265/goodbye-haqqani-network/