{{currentView.title}}

August 02, 2010

The al Qaeda Threat from West Africa and the Maghreb: French Hostage Execution and Beyond

Key Points

- Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has continued to follow through on its anti-French rhetoric and previous operations by killing 78-year-old French hostage Michel Germaneau, whom AQIM was holding in northeastern Mali.

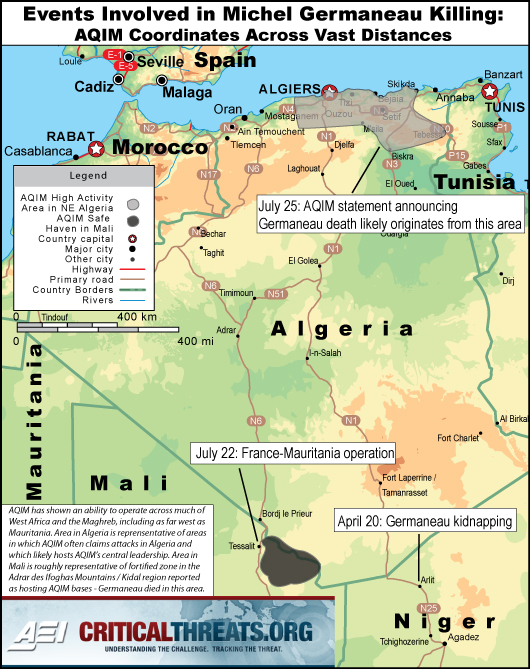

- Details revealed by a July 22 French-Mauritanian raid against AQIM, including the continued existence of a significant AQIM presence in northeastern Mali and AQIM’s rapid response to the operation, prove that AQIM is an entrenched and organized group that continues to threaten Western interests.

- AQIM’s anti-American rhetoric bears a striking resemblance to its anti-French rhetoric. The momentum created by its threats against the U.S. and pressures for high-profile action created by competition for resources and attention within the al Qaeda network mean American policymakers should not take lightly threats the organization has made against U.S. interests.

- The U.S. is in a war against the al Qaeda network, and AQIM forms a critical part of that network as one of three official al Qaeda franchises. The responsibility for defeating AQIM lies with the entire Western alliance, not just France or other European partners. Western security policies have failed to deter the organization and have even failed to contain the group to previous levels of activity, as AQIM has increased its operations in Niger in recent months.

On July 26, French President Nicolas Sarkozy confirmed that al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) had killed French hostage Michel Germaneau, adding that the execution “will not go unpunished.”[1] French Prime Minister Francois Fillon captured French outrage on July 27, stating that France is “at war with al Qaeda.”[2] French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner even began outlining a potential policy response: “France is not pursuing a military escalation. It's just that the [AQIM] people are engaged in a murderous escalation. There is a military option which is being imposed on us.”[3]

These statements come on the heels of a joint French-Mauritanian raid on an AQIM camp in Mali on July 22. Germaneau is the first French hostage killed by AQIM; the group has killed a Western hostage only once before. AQIM has consistently targeted French interests in both word and action. The killing of Germaneau after years of anti-French rhetoric, AQIM’s continued presence in northern Mali, and the AQIM response to the July 22 raid shows that the organization remains a potent threat.

The details of the French-Mauritanian raid provide a glimpse into the scale of the AQIM organization outside Algeria and reveal an image that runs counter to a common portrayal of the group’s Saharan branch as a collection of loosely organized bandits. Mauritanian security forces and 20 to 35 French soldiers supported by planes circling overhead launched the operation from an airport in Tessalit in northeastern Mali.[4] The troops traveled by foot for the last 10 kilometers of the approach to the AQIM camp to avoid detection.[5] The two countries employed a sizeable force, believing they faced a large enemy: Mauritania says it launched the operation to preempt an attack by more than 150 AQIM members upon a military target in Mauritania (the French government has said it also participated as part of a last-ditch effort to save Michel Germaneau).[6] The suspected 150-plus fighters based in Mali represent just a portion of the overall AQIM organization, which maintains a leadership cell likely resident in northeastern Algeria and at least one other branch in Mali led by an individual named Mokhtar bel Mokhtar.[7]

Beyond the size of the AQIM faction, the raid’s location in the Adrar des Iforas Mountains of northeastern Mali suggests that AQIM still maintains some form of a safe haven in the area, despite a July 2009 offensive launched by Malian security forces and other recent counterterror initiatives.[8] A local Malian official said on July 26 that AQIM’s infrastructure in the area “is an impregnable fortress,” complete with mines and bomb shelters.[9] Such entrenchment, likely funded by the revenue AQIM draws from black-market smuggling across the Sahara and the millions of dollars in ransom payments the group collects for releasing hostages, may have made it difficult for the July 22 French-Mauritanian raid and the July 2009 Malian offensive to succeed.[10]

The vast physical distances between events involving Germaneau, the raid, and a July 25 AQIM audio message announcing Germaneau’s killing further display AQIM capacity by revealing an effective command-and-control decision-making structure. Germaneau’s kidnappers seized him near the northern Nigerien town of Arlit, roughly 350-400 miles from the Adrar region in northeastern Mali targeted in the July 22 raid.[11] The Adrar region itself lies across a broad expanse of desert from AQIM’s historical base of operations and likely location of its media operation in northeastern Algeria.[12] Just three days after the French-Mauritanian raid began, AQIM’s public relations operation – likely located more than 1100 miles away, or the rough distance between Washington, DC and Oklahoma City – released an audio statement announcing Germaneau’s death. In the message, AQIM leader Abu Musab al Wadoud declared that Germaneau had been killed on July 24.[13] Some French intelligence sources believe Germaneau, who was originally captured in Niger, may have been dead for weeks. [14] Such a scenario would mean that AQIM leadership simply had to note his death rather than order his execution. Even if Germaneau died prior to July 24, the rapid response shows the flexibility of the AQIM organization to adapt based on developing events. Within hours of the July 22 raid, AQIM’s central leadership established communication with militants holding the hostage and quickly made a decision regarding Germaneau’s fate, if he was still alive at that point in time, and coordinated its public response. Beyond command-and-control and communications, the group also appeared to provide false intelligence to the French, perhaps causing Paris to commit force to an operation (already under development by Mauritania to pre-empt an AQIM operation) under the belief that AQIM was holding Germaneau at the raided camp.

Germaneau’s death advances a long-held AQIM goal to strike at Algeria’s former colonial masters, the French. AQIM grew out of an Islamist tradition in Algeria that has long seen itself as the true defender of an independent Algeria, and dates back to such groups as al Qiyam (“the Values”), which was founded in the 1960s. [15] The Algerian Islamist movement’s nationalist ideals sharpened during years of modernization, eventually embracing unfettered violence after the Algerian military annulled the result of the country’s 1992 elections. The movement views its opponents in the Algerian government as remnants of the French colonial overlords that Algerians defeated during the 1954-1962 Algerian war for independence.[16] One of the violent Islamist groups formed in the 1990s was the Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA) or the Armed Islamic Group; out of the GIA, a group known as the Groupe Salafiste Pour la Prédication et le Combat (GSPC), or the Salafist Group for Call and Combat, eventually emerged. The GSPC changed its name to AQIM in January 2007, four months after Ayman al Zawahiri, the deputy leader of al Qaeda, officially declared it an al Qaeda franchise in September 2006.[17]

AQIM’s nationalist origins make French interests a natural target, and the group’s rhetoric reflects this focus through frequent threats against France. In July 2007, Wadoud said “between France and the Muslims is still a wall of skulls and body parts and a sea of tears and blood that separates them.”[18] The group views its enemies in the Algerian government as French puppets, calling them “sons of France” who answer to “masters in Élysée Palace.”[19] One statement said of the Algerian regime, “These oppressive apostate rulers are a class of westernized Francophones who were raised under the eye of France and drank of its milk.”[20] AQIM propaganda has reinforced these words with imagery: one March 2008 video showed a picture of Sarkozy with Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, reinforcing the connection between Algiers and Paris.[21] AQIM’s superiors in the al Qaeda network have encouraged the focus on France. In his September 2006 message welcoming the group to al Qaeda, Zawahiri said that the group’s “union” with al Qaeda would be a “bone in the throats of the American and French Crusaders and their allies...”[22] A year later, Zawahiri called for the organization to target France and Spain.[23] Beyond Germaneau’s execution, other recent actions the group has taken against French interests include attacking French workers in Algeria in September 2007, French tourists in Mauritania in December 2007, and the French embassy in Mauritania in August 2009.[24] Reveling in Germaneau’s death, Wadoud said in a statement published in full on July 30:

AQIM has only killed one other Western hostage. Abou Zeid, an AQIM commander who also held Germaneau and who has responsibility for a part of AQIM’s area of operations in the Sahelian-Saharan desert region (which includes parts of southern Algeria, Mauritania, Mali, and Niger), executed British citizen Edwin Dyer last year after the United Kingdom did not meet AQIM’s demand to release Abu Qatada, a key European lieutenant for Osama bin Laden who has been fighting deportation from the U.K. to Jordan for years.[26]

AQIM chose not to kill Pierre Camatte, another French hostage captured by the group in November 2009 and released in February 2010.[27] Zeid also held Camatte, meaning that the decision to release Camatte cannot be attributed to separate styles between different AQIM factions.[28] Zeid and AQIM leader Wadoud may simply have chosen to release Camatte because Mali met AQIM’s demand to release four militants from prison.[29] In the case of Germaneau, AQIM may have wished to show strength against the West, expose the partial failure of the July 22 raid, and retaliate against France for not meeting its demands (the group had sent France a list of prisoners it demanded released in exchange for Germaneau’s freedom).[30] By executing Germaneau, the group has stated that AQIM’s demands must be met and that rescue attempts will result in dead hostages. Even if Germaneau died prior to the July 22 raid, the method and speed by which the group chose to present his death sends the same message.

AQIM also likely intends the killing of Germaneau to show that the West should take its threats as seriously as its ransom demands. Throughout AQIM propaganda, the U.S. receives treatment parallel to that given to France. AQIM uses strikingly similar wording in threatening the U.S., calling the Algerian regime “slaves of America” who have “masters…in the White House.”[31] One AQIM video shows American forces training Algerian forces, making explicit its argument that targeting the Algerian regime equates to targeting Washington. Such a message elevates the group’s fight against the Algerian government in the process, but also creates rhetorical momentum for attacks directly against U.S. interests.[32] To date, AQIM has killed only one American: the aid worker Christopher Leggett, shot in the streets of the Mauritanian capital of Noaukchott in June 2009.[33] AQIM has had more opportunity to strike French interests than American ones, but the similarity between its anti-French and anti-American rhetoric and the process by which AQIM has targeted France likely indicate that its ambitions for attacking Americans and American interests go far beyond Leggett’s death.

AQIM’s continued safe haven in northern Mali, the significant size of its personnel, its command-and-control and information operations campaign, and its ability to carry out threats mean that the organization continues to present a threat that the West has not yet sufficiently addressed.

The West and regional partners have taken the group seriously. In October 2009, the U.S. provided $4.5 million worth of military communications equipment and vehicles to Mali.[34] Algeria, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger established a joint military headquarters in April 2010 in the southern Algerian city of Tamanrasset, just a few hundred miles from both the location in northern Niger where AQIM kidnapped Germaneau and the AQIM stronghold in northeastern Mali targeted by the July 22 French-Mauritanian raid.[35] A month later, the U.S. conducted Operation Flintlock with several regional partners, including Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Senegal, to train for improved operations against AQIM.[36] Yet this joint activity has failed to deny territory to AQIM or dismantle AQIM camps or safe havens.

The French-Mauritanian operation did not appear to involve all regional partners in the manner set forth by previous joint exercises: France apparently informed Mali and Algeria of the operation but did not consult them.[37] This may be because France and Mauritania wished to maintain a degree of surprise and did not trust Malian officials to keep the operation confidential.[38] They may also have made the calculation that Mali, which earlier in July 2010 allowed Algerian troops to cross the Malian border in pursuit of al Qaeda, could not add value to the raid through a force contribution.[39] Indeed, the July 2009 Malian offensive failed to dismantle the AQIM safe haven and saw the loss of at least sixteen Malian soldiers in one ambush.[40]

In a meeting with French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner on July 27, Malian President Toumani Toure urged, in an apparent reference to the lack of Malian involvement in the July 22 raid, that future military operations be coordinated with regional partners like Mali. Kouchner agreed and also stated that he and Toure both wish “that there should be more large scale operations against [AQIM].”[41] Any reconsideration of Western security policy towards West Africa and the Maghreb should take such concerns into account, understanding that different levels of multilateral cooperation and different scales of operations can each have merit depending on environmental factors and mission goals. The type of operation necessary to eject AQIM from its Malian safe haven, however, will likely require a significant amount of force and participation from multiple regional partners. The return of Algeria’s ambassador to Mali on July 29, five months after his recall in February, will prepare the ground for such multilateral operations by lessening some of the intra-regional tensions over anti-AQIM policy.[42]

AQIM has continued to conduct operations and maintain communication between factions located across thousand-mile-plus distances, despite efforts by Sahel and Maghreb states and their Western allies.[43] Its traditional base of operations lies in northeastern Algeria and it has established some form of safe haven in northeastern Mali. AQIM-linked operations between fall 2006 and late 2008 focused on targets in Algeria, Mauritania, and Mali, except for one kidnapping in Tunisia in February 2008.

In the last year-and-a-half, however, AQIM has managed to significantly increase activity in Niger, which already has experienced a coup, famine, and drought in 2010. In December 2008, AQIM kidnapped two Canadian diplomats, Robert Fowler and Louis Guay, while they visited a gold mine in Niger.[44] A month later, four Europeans, including Dyer, fell into AQIM’s hands while attending a Tuareg festival in Mali close to the Niger border.[45] Activity has accelerated even more over the last nine months. In November 2009, AQIM was believed linked to an attempted kidnapping of U.S. embassy personnel.[46] In December 2009, unidentified armed individuals linked to AQIM attacked a village in the northwestern Nigerien region of Tahoua, killing ten, including seven soldiers; also, that month, AQIM members killed three Saudi tourists who were travelling to Mali from the Nigerien capital of Niamey.[47] On March 8, five Nigerien soldiers died in an attack, later claimed by AQIM, upon an army post in the Tillaberry region of northwestern Niger.[48] The group kidnapped Germaneau in northern Niger on April 20 or 22.[49]

The continued failure of Western and African security policies to dislodge or even contain AQIM should force a reassessment of strategy in the region. It is true that AQIM has not been able to conduct an attack in Europe, a goal Zawahiri likely envisioned for the group.[50] Yet its failure to achieve that goal does not necessarily indicate a lack of capacity to do so in the future. AQIM, as an official al Qaeda franchise, will continue to compete with groups like al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the al Qaeda-linked al Shabaab for recruits, fundraising, and attention from al Qaeda central. As part of this competition, AQIM will use the Germaneau execution to increase its appeal and strength. It will also attempt to increase its attacks against the interests of the West and Western allies. The continued competitive pressures upon the group, its ability to follow through on threats, and its continued capacity to operate across a wide swath of territory means AQIM may present a greater danger in the months and years to come. Only a shift to a policy that rolls back AQIM will reduce the threat it poses to the U.S., France, and their allies inside and outside Africa.

American policymakers in particular should take note of the group and recognize that the similarities between its anti-American and anti-French rhetoric may mean that AQIM has not conducted repeated attacks against American interests because of a lack of opportunity, not a lack of desire. The group may choose to attack the U.S. and its interests should its capacity change or opportunities present themselves. The 2010 U.S. National Security Strategy states that the U.S. is in “a war against al-Qa’ida and its affiliates.”[51] AQIM forms a critical segment of that network as one of al Qaeda’s three official franchises. The two other franchises have tried to or managed to kill large numbers of Americans in recent years. The group’s continued threat cannot just be a French or European problem, but rather a challenge for the entire Western alliance.