What Zawahiri’s Death Means for al Qaeda

August 02, 2022

What Zawahiri’s Death Means for al Qaeda

On August 1, President Joe Biden announced a US strike killed al Qaeda’s top leader, Ayman al Zawahiri, in Kabul, Afghanistan. Thanks to the many professionals who made the strike possible, as the president said, “Justice has been delivered.” Zawahiri’s death is a major counterterrorism victory—on par with that of Osama bin Laden and Abu Bakr al Baghdadi—but it’s not the end of America’s counterterrorism fight.

Zawahiri’s terrorism credentials stretch back decades. He fled Egypt in the mid-1980s, ending up in Afghanistan where his ideas of jihad greatly influence bin Laden. Zawahiri’s Egyptian Islamic Jihad group worked closely with al Qaeda and had effectively merged with the group by 1998, a merger formalized in June 2001. That puts Zawahiri by bin Laden’s side during al Qaeda’s deadliest attacks targeting Americans—the 1998 East African embassy bombings, the 2000 USS Cole bombing, and 9/11. Ten years later, Zawahiri succeeded bin Laden to lead al Qaeda.

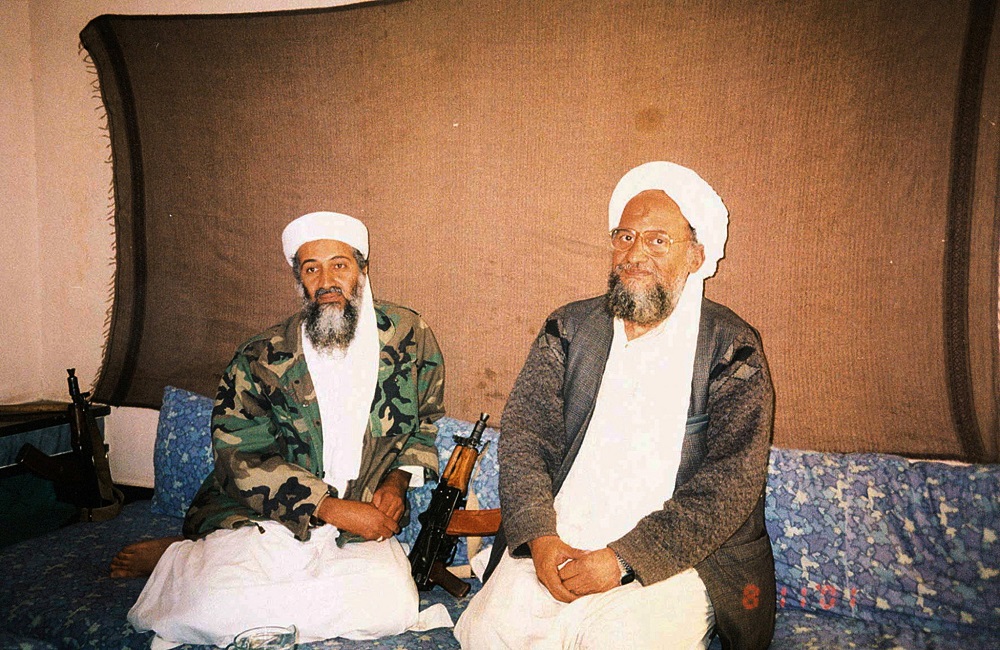

FILE PHOTO: Osama bin Laden sits with his adviser Ayman al-Zawahiri, an Egyptian linked to the al Qaeda network, during an interview with Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir (not pictured) in an image supplied by Dawn newspaper November 10, 2001. Hamid Mir/Editor/Ausaf Newspaper for Daily Dawn/Handout via REUTERS/ THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY./File Photo

FILE PHOTO: Osama bin Laden sits with his adviser Ayman al-Zawahiri, an Egyptian linked to the al Qaeda network, during an interview with Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir (not pictured) in an image supplied by Dawn newspaper November 10, 2001. Hamid Mir/Editor/Ausaf Newspaper for Daily Dawn/Handout via REUTERS/ THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY./File PhotoDespite al Qaeda not having orchestrated a successful major attack under Zawahiri, his tenure was largely a success measured by al Qaeda’s own metrics. Al Qaeda’s influence on the ground within the Muslim world, especially in parts of Africa, has grown considerably—and dangerously—in the past eleven years. Al Qaeda survived the challenge from the Islamic State, not only remaining relevant but also positioning itself for continued growth. The terror network weathered US counterterrorism pressure and has cultivated a new generation of leaders to carry al Qaeda’s work forward. Zawahiri, characteristically uncharismatic, still commanded loyalty and provided strategic direction to his followers globally.

The question of what’s next for al Qaeda looms large. The Obama administration was quick to declare al Qaeda’s demise after the death of bin Laden, which Team Biden seems to be smartly avoiding. Who takes Zawahiri’s spot at the top will be crucial for the direction of the global terror network. Saif al Adel, a contemporary of bin Laden and Zawahiri, is an obvious candidate and well-versed in running militant operations. Whomever al Qaeda names will inherit not bin Laden’s al Qaeda, but Zawahiri’s: an al Qaeda that has embedded deeply in local contexts, still oriented on global jihad but advancing its aims locally.

Today’s al Qaeda is a global network with local branches. Al Qaeda’s senior leaders are dispersed among those branches—al Qaeda’s number three leader has been in North Africa and the late number two was in Yemen—as well as finding sanctuary in places like Afghanistan under the Taliban and Iran. The branches follow senior leader guidance, but their fortunes do not rest on the shoulders of one man or some group of leaders. Rather, they each draw strength by tapping into the grievances of local communities and building relationships with those who share common short-term goals. Counterterrorism operations will eliminate leaders and disrupt networks, but they will not erase the ground conditions that enable al Qaeda groups to grow.

Particularly in Africa, al Qaeda’s affiliates are strengthening. In Somalia, al Shabaab conducted a major incursion into Ethiopia just a few months after President Biden authorized the redeployment of US troops in support of ongoing counterterrorism operations. So long as al Shabaab provides better governance options than the Somali government, it will be able to rebound from setbacks. Meanwhile in Mali, counterterrorism pressure is lifting on al Qaeda’s local branch. France’s drawdown has created opportunities for the group to expand southward, striking in regions never before targeted. The security-based counterterrorism approaches have not made lasting gains against al Qaeda, and at least al Shabaab has sought to target American interests in a 9/11-style plot disrupted in 2019. The US should be prepared for another attempt.

The US killed al Qaeda’s leader, but as before, al Qaeda and its threat lives on.