Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Africa File: Al Qaeda’s Sahel branch escalates attacks

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Al Qaeda affiliates are strengthening in Africa. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo emphasized the persistent al Qaeda threat on January 12. Secretary Pompeo’s remarks focused on the Iran-based al Qaeda node but also warned that al Qaeda’s position in Somalia could become a source of international terror attacks. Al Shabaab, al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, has increased its efforts to conduct international attacks; a member of the group was recently charged with planning a 9/11-style attack. Meanwhile, al Qaeda’s Mali branch has escalated attacks in the Sahel region, including a series of explosive attacks targeting French and UN security personnel. The commander of the French counterterrorism mission in Mali identified an al Qaeda branch as the most dangerous terrorist group in the country.

In this Africa File:

- Sahel. Suspected Islamic State militants conducted the deadliest attack against civilians in Niger’s history. Al Qaeda’s Sahel branch increased attacks on French and UN forces and sought to present itself as a defender of civilians against French forces.

- Somalia. Al Shabaab propaganda emphasized its external attack ambitions.

- Ethiopia. Sudanese-Ethiopian relations are deteriorating. Ethnic-based violence is escalating in several Ethiopian regions.

- Mozambique. Islamic State–linked militants staged their closest attack yet to foreign natural gas facilities in northern Mozambique.

Latest publications:

- Ethiopia. CTP is publishing updates on the Ethiopia crisis. Sign up to receive the latest updates by email here. Read Jessica Kocan’s latest update here and Emily Estelle’s background on the conflict here.

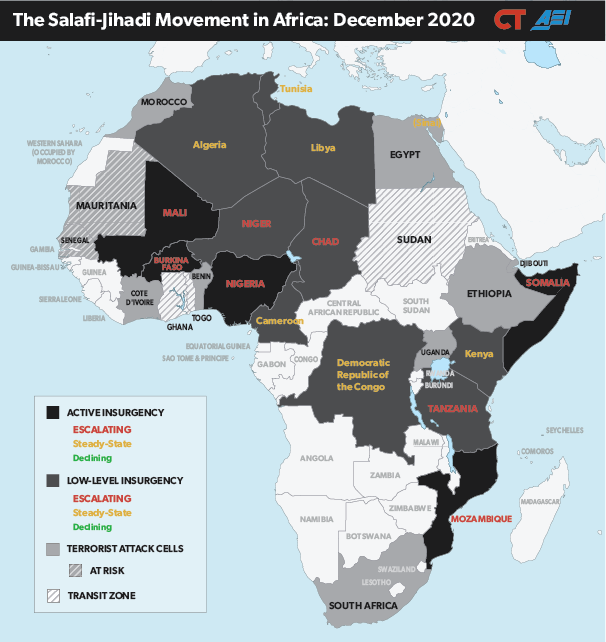

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: December 2020

View full image.

Source: Emily Estelle.

Read Further On:

Overview: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated January 15, 2021

The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is active across northern, eastern, and western Africa and is expanding and deepening its presence on the continent. This movement, like any insurgency, draws strength from access to vulnerable and aggrieved populations. Converging trends, including failing states and regional instability, are creating favorable conditions for the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion. Meanwhile, continued counterterrorism efforts rely on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding, and on states and local authorities that have demonstrated an inability to govern effectively.

West Africa. The Salafi-jihadi movement has spread rapidly in West Africa by exploiting ethnic grievances and state weaknesses that include human rights abuses, corruption, and ineffectiveness. An al Qaeda affiliate co-opted the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and has continued to expand southward through the Sahel region into central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. Sahel groups have not yet plotted attacks outside of West Africa but have sought to drive Western security and economic presence out of the region while building lucrative smuggling and kidnapping-for-ransom enterprises. An al Qaeda–linked group in Mali is infiltrating governance structures, advancing an overarching Salafi-jihadi objective. West Africa has become an area of focus for transnational Salafi-jihadi organizations, with rival jihadists now fighting for dominance in the Sahel.

The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate is based in northwest Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—and conducts frequent attacks into neighboring states. Boko Haram and an al Qaeda–linked splinter group are also active in this region.

East Africa. Al Shabaab, an al Qaeda affiliate and the dominant Salafi-jihadi group in East Africa, is vocal about its intent to attack US interests and has begun to plot international terror attacks. The group enjoys de facto control over broad swathes of southern Somalia and can project power in the Somali federal capital Mogadishu and regional capitals where it regularly attacks senior officials. It seeks to delegitimize and replace the weak Somali Federal Government—a task made easier by endemic political dysfunction and corruption in Mogadishu. Al Shabaab’s governance ambitions extend into Kenya and Ethiopia, as it claims to seek to unite the Somali ethnic group.

Al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from eroding security conditions in East Africa. Ethiopia’s destabilization is already having regional effects, including weakening counter–al Shabaab efforts inside Somalia. The drawing down of the US and African Union counterterrorism missions in Somalia will also reduce pressure on al Shabaab.

The Islamic State has also penetrated the region. Islamic State branches are now active in northern Somalia, the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Mozambique bordering Tanzania, where its affiliate seized a Mozambican port in August 2020 that it still controls. The Islamic State foothold in Mozambique marks the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion into southern Africa.

North Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups in North Africa are at a low point, but the fragility and grievances that led to their rise remain. The Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent security vacuums allowed Salafi-jihadi groups to organize and forge ties with desperate and coerced populations. The rise of the Islamic State brought a peak in Salafi-jihadi activity in North Africa, particularly from its branches in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Counterterrorism pressure has weakened Salafi-jihadi groups across North Africa in the past five years. The insurgencies in Libya and Sinai are active but contained, and terrorist attacks across the region have decreased. Libya’s war will continue to create opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups, and severe instability or collapse in any North African state would likely bring the Salafi-jihadi threat back to the surface.

West Africa

Sahel

Suspected Islamic State militants conducted the deadliest attack against civilians in Niger’s history. Militants on motorbikes simultaneously *attacked two villages in western Niger’s Tillabery region on January 2, killing at least 100 civilians and wounding 75. The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) is likely responsible for this attack. One local leader *identified a senior ISGS militant as the attack leader.

ISGS is present in western Niger, and the latest massacre fits its brutal modus operandi. ISGS has claimed some of the most lethal attacks against civilians throughout the Sahel region in recent years. ISGS is also the most active Salafi-jihadi group in western and southwestern Niger; it is likely responsible for an attack that killed eight civilians, including six French aid workers, in western Niger on August 9, 2020.

The details of the January 2, 2021, attack indicate that ISGS is attempting to control civilian behavior in western Niger, an area where state security forces are largely absent. A victim stated that the attackers were militants who had *previously entered the villages to collect zakat (religious tax). The villagers killed the two militants extorting them. The militants attacked in retaliation the next day to assert dominance over the population.

This attack occurred as Niger held presidential elections marking the country’s first peaceful transition of power. Niger is a US security partner that faces several security challenges, including Salafi-jihadi insurgencies on its western and southeastern borders.

Al Qaeda–linked Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), which operates along the Niger-Mali-Burkina Faso border, denied responsibility for the January 2 attack and denounced the targeting of civilians.[iii] JNIM presents itself as more lenient than ISGS and distinguishes itself through its willingness to negotiate and ally with local and governmental leaders. JNIM has been quick to condemn attacks against civilians.

Malian civilians accused French forces of striking a wedding party amid confusion over an unclaimed attack. French forces *announced an air strike killing 12 militants in Bounti village in central Mali’s Mopti region on January 3. What appeared to be a second strike killed 20 civilians in Bounti on the same day. Bounti villagers are accusing the French of targeting civilians and making false claims. CORRECTION NOTE:A prior version of this Africa File incorrectly stated that French forces reported that an unidentified helicopter fired on a wedding party. Villagers described the helicopter attack to AFP, and French forces only stated that they had not used a helicopter in their operations and that their operations did not cause collateral damage. They did not confirm that any helicopter attack occurred and were not the sources for the AFP story.Villagers stated that an unidentified helicopter fired on a wedding party. French forces returned to Bounti on January 8 to investigate the attack. French officials stated that a helicopter was not used in the French operation and restated that the operation did not cause collateral damage.

A Malian army spokesman denounced civilian anti-French claims as propaganda. The Malian army *announced January 6 that it will open an investigation to better understand the January 3 attack.

Malian *human rights groups *criticized military operations in civilian areas, called for independent investigations to shed light on the event, and have *planned for an anti-French protest in Bamako on January 20.

Al Qaeda’s branch in the Sahel intensified its anti-French rhetoric in response to the Bounti attack. JNIM mourned civilians’ deaths and blamed France for the attack in its newsletter. The group also claimed two attacks against French and UN forces on January 8, stating the attacks were in retaliation for France’s alleged attack against civilians.[iv]

Al Qaeda’s General Command (AQGC) also released a statement in early January calling on its supporters to boycott and attack French interests in response to France republishing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in December 2020. JNIM claimed it has been and will continue to attack the French in a direct response to the AQGC statement. JNIM seeks to expel foreign forces such as the French, the group’s main external enemy, from Mali as part of al Qaeda’s overarching effort to remove non-Muslims from Muslim lands. JNIM has called on the Malian government to expel French forces as a precondition for negotiations to end hostilities.

JNIM has increased its attacks against French forces in Mali following anti-Muslim rhetoric in France. JNIM has claimed several attacks against French forces inside Mali since December 2020 in response to French magazine Charlie Hebdo’s depictions of the Prophet Muhammad.[v] JNIM also claimed two attacks on French, Malian, and UN troops as revenge for the January 3 attack on civilians in central Mali that JNIM has attributed to France, including an improvised explosive device (IED) attack that killed two French soldiers in eastern Mali on January 9.[vi] A JNIM IED attack also killed three French soldiers in late December. Suspected JNIM militants attacked a UN vehicle in northern Mali on January 13, killing three peacekeepers and injuring six.

French officials have adjusted their threat assessment in response to JNIM’s growing capability. French Operation Barkhane Commander Marc Conruyt described JNIM as the most dangerous group in Mali after a JNIM attack killed two French soldiers on January 9. French President Emmanuel Macron had previously deemed ISGS the most dangerous group in the Sahel in 2020. A French Barkhane officer claimed JNIM gained territory in recent months despite French and Malian counterterrorism operations. The group has improved its ability to conduct simultaneous coordinated attacks.

Forecast: JNIM’s heightened attack tempo will limit the movement of counterterrorism forces and lead to an effective stalemate, with JNIM preserving its current area of operations and deepening its influence over local populations. JNIM will likely exploit anti-French rhetoric to gain local support and may form mutually beneficial alliances with local populations frustrated by a lack of government presence, including recruiting members from these populations. (Updated January 15, 2021)

East Africa

Somalia

Al Shabaab propaganda emphasized its external attack ambitions. Al Shabaab has recently focused its messaging on striking US interests. The group’s leader, Ahmad Umar, urged supporters to intensify attacks against the US and its Western allies in a January 3 statement.[i] Umar’s speech marked the one-year anniversary of the first and only al Shabaab attack on a US military position in Kenya in January 2020. The attack on the Manda Bay base killed three US citizens. Umar said the group carried out the Manda Bay attack under AQGC’s “Jerusalem will never be Judaized” campaign, which targets US interests in retaliation for the Donald Trump administration’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in 2018. Separately, al Shabaab praised al Qaeda’s Malian affiliate on January 5 for killing two French soldiers and for engaging in its own “Jerusalem will never be Judaized” campaign.[ii]

Conditions in East Africa increasingly favor al Shabaab’s ambitions to stage an external attack. A New York City court indicted a Kenyan al Shabaab member in December 2020 for planning a 9/11-style attack in a major US city. He is the second detained al Shabaab militant planning to hijack a plane over the past two years.

Pressure on al Shabaab’s Somali stronghold is decreasing. The US began withdrawing troops from Somalia in late December and plans to complete its withdrawal by January 15. This withdrawal comes as neighboring Ethiopia’s domestic crisis and Somalia’s severed diplomatic ties with Kenya disrupt counter–al Shabaab operations in the country.

Ethiopia

Ethiopian federal troops continue to fight for control of northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region. Ethiopian federal forces captured the Tigray capital, Mekelle, from the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in late November. TPLF leadership fled west of Mekelle and federal forces have continued fighting in other parts of Tigray since. Ethiopia’s military has claimed to kill or capture TPLF members throughout early January, most recently claiming to *kill three former TPLF members, one of whom was Ethiopia’s former foreign minister, on January 13.

The TPLF was the leading component of Ethiopia’s ruling party until Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed took power in 2018. Ethiopian federal forces entered Tigray in November 2020 to wrest control from the TPLF following escalating tensions between the TPLF and Abiy’s administration.

Sudanese-Ethiopian relations are deteriorating. Sudanese armed forces have clashed with Ethiopian soldiers and armed Ethiopian farmers along the Sudanese-Ethiopian border since December. Sudanese forces took advantage of the distraction created by the Tigray conflict in northern Ethiopia to seize disputed territory in the Fashqa triangle in early December. Relations between the two countries have also soured over deadlocked Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) negotiations. For more on Sudan-Ethiopia relations, see the latest Ethiopia Crisis update.

Ethnic violence is escalating across multiple regions, posing a serious challenge to the federal government’s control and the country’s cohesion. The violence has most recently spiked in Benishangul-Gumuz region in western Ethiopia. Ethnic Gumuz targeted Amhara and members of other ethnic groups in late December. Suspected ethnic Gumuz most recently killed over 80 civilians in the region’s Metekel Zone, where the GERD is located, on January 12, targeting ethnic Amhara and Agaw. Violence against Amhara civilians has also *spiked in west-central Ethiopia’s Oromia region, which has been restive throughout Abiy’s administration.

This violence reflects an overarching challenge to Ethiopia’s stability as the Tigray conflict shifts power dynamics, ethnic-based armed groups mobilize in response to localized grievances, and the federal government becomes increasingly reliant on select ethnic-based militias. The federal government’s reliance on Amhara regional forces in the Tigray conflict and now in Benishangul-Gumuz risks further inflaming ethnic tensions and irreparably damaging the federal government’s reputation with other constituencies.

Forecast: Sudan and Ethiopia’s relationship will continue to deteriorate if the two countries are unable to resolve a territorial dispute along their shared border. Prolonged conflict will gradually weaken Ethiopia’s institutions while encouraging unrest in other parts of the country, increasing the risks of fragmentation, secession, and foreign meddling. Salafi-jihadi groups like al Shabaab, which have a limited presence in Ethiopia, will take advantage of Ethiopia’s destabilization to begin conducting intermittent attacks in the next year. (Updated January 15, 2021)

Mozambique

Islamic State–linked militants staged their closest attack yet to foreign natural gas facilities in northern Mozambique. The militants were advancing through villages in Palma district in Cabo Delgado province toward French company Total’s liquified natural gas plant since mid-December. The militants attacked Monjane village roughly three miles away from the plant’s fenced perimeter on December 29. They attacked Quitunda village outside the plant’s fenced perimeter on January 1. This attack prompted Total to reduce its workforce over safety concerns.

Militants launched an insurgency in Cabo Delgado, a remote and resource-rich province in northern Mozambique, in late 2017. The group notably improved its attack capability in early 2019 and pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in that year. Islamic State–linked militants have controlled a port in Cabo Delgado since August 2020 and have begun limited cross-border attacks into neighboring Tanzania. Mozambican forces have struggled to regain territory; the militants have repeatedly recaptured territory from government forces over the past two months.

Forecast: Salafi-jihadi militants may attempt an attack on Total’s plant in the next three to six months, though they may not have the capability to breach the facility. The militants’ continued presence around the plant will prolong a disruption in foreign investment. (As of January 15, 2021)

[i] “Commemorating One-Year Anniversary of Manda Bay Raid, Shabaab Leader Urges Continued Fighting Against U.S. and West by Individuals and Groups,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 3, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[ii] “Shabaab Lauds JNIM for Recent Operations Against French Forces in Mali, Urges Other Jihadi Groups Follow Example,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 5, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[iii] “JNIM Claims Killing 2 French Troops in IED Blast Near Ménaka, Disavows Massacres in Western Niger,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 4, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[iv] “JNIM Claims Suicide Bombing, Rocket Attack in Retaliation for French Drone Strike on Alleged Wedding Party in Mali,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 14, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[v] “In Formal Communique, JNIM Claims Strikes on French Camps and Personnel in Mali as Revenge for Prophet Muhammad,” SITE Intelligence Group, December 4, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[vi] “JNIM Claims Suicide Bombing, Rocket Attack in Retaliation for French Drone Strike on Alleged Wedding Party in Mali,” SITE Intelligence Group, January 14, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.