Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Africa File: Political instability threatens counterterrorism gains in Maghreb, Sahel, and Horn

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Protracted political crises in Libya and Somalia risk undercutting gains that have been made against Salafi-jihadi groups in recent years. An uptick in intermilitia clashes in Tripoli is a warning sign that the country’s fragile peace deal may not hold through and after elections in December. Meanwhile, the Islamic State in Libya has been slowly regaining capability, though it remains a shadow of its former self. In Somalia, a long-running political crisis surged again, risking renewed confrontation between security forces in Mogadishu and the drawing of resources away from the fight against al Shabaab. Separately, a military coup in Guinea is the latest in a string of coups and leadership changes across the Sahel region, underscoring the persistent weakness of local governments at a time when Salafi-jihadi groups are cementing their positions and increasing attacks on civilians.

In this Africa File:

- Libya. Security is deteriorating in western Libya, indicating the interim government’s inability to control militias in Tripoli.

- Somalia. The renewed political crisis in Somalia risks derailing the country’s elections and creating opportunities for al Shabaab to strengthen.

- Ethiopia. Conflict is worsening the humanitarian crisis in northern Ethiopia.

- Mozambique and Tanzania. Islamic State–linked insurgents are retreating southward after losing control of a port in northern Mozambique.

- Sahel. Salafi-jihadi groups increased attacks on civilians in Mali in 2021. Unconfirmed reports claim the Islamic State’s leader in the Sahel was killed. The Guinea coup may affect counterterrorism efforts.

Latest publications:

- The Salafi-jihadi movement. Katherine Zimmerman lays out the state of play for al Qaeda and the Islamic State 20 years after the September 11 attacks. Read her primer and view the graphic here.

Read Further On:

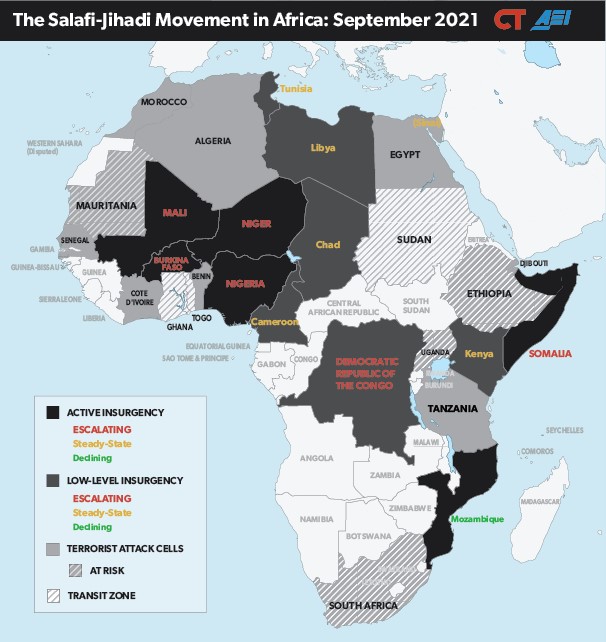

Figure 1. The Salafi-jihadi movement in Africa: September 2021

View full map.

Source: Authors.

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

Overview: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated August 26, 2021

The Salafi-jihadi movement, which includes al Qaeda and the Islamic State, is active across Northern, Eastern, and Western Africa and is expanding and deepening its presence on the continent (Figure 1). This movement, like any insurgency, draws strength from access to vulnerable and aggrieved populations. Converging trends, including failing states and regional instability, are creating favorable conditions for the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion. Meanwhile, counterterrorism pressure relies on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding, and on states and local authorities that have demonstrated an inability to govern effectively. The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021 is a watershed moment for the global Salafi-jihadi movement that reaffirms the strategies of African al Qaeda affiliates and may energize ongoing insurgencies.

West Africa. The Salafi-jihadi movement has spread rapidly in West Africa by exploiting ethnic grievances and state weaknesses that include human rights abuses, corruption, and ineffectiveness. An al Qaeda affiliate co-opted the 2012 Tuareg rebellion in Mali and has continued to expand southward through the Sahel region into central Mali and the peripheries of Burkina Faso. An Islamic State–linked group is active in the same area, particularly western Niger and parts of Burkina Faso.

Sahel groups have not yet plotted attacks outside West Africa but have sought to drive Western security and economic presence out of the region while building lucrative smuggling and kidnapping-for-ransom enterprises. An al Qaeda–linked group in Mali is infiltrating governance structures, advancing an overarching Salafi-jihadi objective, and expanding into Gulf of Guinea countries. West Africa has become an area of focus for transnational Salafi-jihadi organizations, with rival jihadists now fighting for dominance in the Sahel. Meanwhile, political instability, particularly in Mali, threatens local and international counterterrorism efforts.

The Islamic State’s largest African affiliate is based in northwest Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—and conducts frequent attacks into neighboring Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Boko Haram and an al Qaeda–linked splinter group are also active in this region. The death of Boko Haram’s longtime leader in May 2021 is weakening the group and benefiting the Islamic State’s Nigerian branch.

New instability in Chad, whose longtime president was killed in April 2021, may lift pressure from Salafi-jihadi groups in both Mali and the Lake Chad Basin, where Chadian forces participate in regional counterterrorism efforts.

East Africa. Al Shabaab, an al Qaeda affiliate and the dominant Salafi-jihadi group in East Africa, is vocal about its intent to attack US interests and has begun to plot international terror attacks. The group enjoys de facto control over broad swaths of southern Somalia and can project power in the Somali federal capital Mogadishu and regional capitals, where it regularly attacks senior officials. It seeks to delegitimize and replace the weak Somali Federal Government—a task made easier by endemic political dysfunction, corruption, and an ongoing constitutional crisis. Al Shabaab’s governance ambitions extend to ethnic Somali populations in Kenya and Ethiopia, and the group conducts regular attacks in eastern Kenya.

Al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from eroding security conditions in East Africa. Ethiopia’s destabilization is already having regional effects, including weakening counter–al Shabaab efforts in Somalia. The drawing down of the US and African Union counterterrorism missions in Somalia will also reduce pressure on al Shabaab.

The Islamic State has also penetrated the region. Islamic State branches are now active in northern Somalia, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northern Mozambique, bordering Tanzania. The insurgency caused French company Total to shutter a multibillion-dollar natural gas project in northern Mozambique that was the continent’s largest private investment. The Islamic State foothold in Mozambique also marks the Salafi-jihadi movement’s expansion into southern Africa.

North Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups in North Africa are at a low point, but the fragility and grievances that led to their rise remain. The Arab Spring uprisings and subsequent security vacuums allowed Salafi-jihadi groups to organize and forge ties with desperate and coerced populations. The Islamic State’s rise brought a peak in Salafi-jihadi activity in North Africa, particularly from its branches in Libya and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Counterterrorism pressure has weakened Salafi-jihadi groups across North Africa in the past five years.

The insurgencies in Libya and Sinai are active but contained, and terrorist attacks across the region have decreased. Libya’s political and security crisis will continue to create opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups, and severe instability or collapse in any North African state would likely bring the Salafi-jihadi threat back to the surface. The Tunisian political crisis that began in mid-2021 poses a potential threat to the country’s gains against the Salafi-jihadi movement.

North Africa

Libya

Security is deteriorating in western Libya, indicating the interim government’s inability to control militias in Tripoli. Clashes have broken out between multiple militias nominally aligned with the Government of National Unity (GNU) over control of state institutions. A militia formally aligned with the GNU’s Presidential Council has clashed several times with other western Libyan militias, an increase in engagements after sporadic clashes in June and July. The Presidential Council theoretically commands the western Libyan army, which comprises numerous militia groups under the GNU’s disjointed apparatus. Former Libyan Prime Minister Fayez al Serraj *formed the Presidential Council militia, known as the Stability Support Apparatus (SSA), in January 2021.

The SSA may be vying for control over state institutions. It stormed the GNU’s Ministry of Interior (MOI) headquarters and arrested an MOI aid on August 25. The MOI is tasked with ensuring the security of Libyan elections in December 2021. The SSA and the MOI-aligned Nawasi Brigade clashed at the Administrative Control Authority headquarters in Tripoli on August 31. The Administrative Control Authority oversees government performance and has the power to challenge appointments to public positions and dispute the control of other state institutions.

GNU political disputes may have caused some clashes. The SSA *clashed with a militia aligned with the GNU Ministry of Defense (MOD), the 444 Brigade, in southern Tripoli between September 3 and 4. Disputes within the MOD could have caused the clash. An MOD leader indicated that the fighting was aimed at curbing the activities of the 444 Brigade due to a 444 Brigade leader *failing to comply with orders. Broader political disputes may have also caused the clashes. GNU Prime Minister Abdelhamid Dbeibeh appointed himself as the defense minister, a move that the Presidential Council has *contested. Dbeibeh also has close ties with the 444 Brigade.

The clashes could cause other Tripoli militias to mobilize in support of the SSA or 444 Brigade. A Zawiya militia arrived in southern Tripoli on September 3, likely to reinforce the 444 Brigade. Suspected SSA members targeted the same Zawiya militia in a drive-by shooting on August 26, injuring the militia’s leader. Similar clashes will likely occur throughout Tripoli, but an apology from an MOD leader and a GNU *investigation into the incident will likely deescalate the conflict in the short term.

Violence in Tripoli could extend toward the south after attacks on a major water supply in southwestern Libya. The Great Man-Made River (GMMR) station in southwestern Ash Shwayrif supplies water to several western cities, including Tripoli. Unidentified attackers bombed the GMMR station in Ash Shwayrif on July 29. An armed group forced the closure of the GMMR and *demanded the release of the former head of Libyan intelligence, Abdullah al Senussi, from Mitiga prison in Tripoli on August 11.

The group is likely affiliated with Senussi’s Magarha tribe. The Magarha tribe cut water to Tripoli and demanded the release of prisoners in April 2020. The recent clashes in Tripoli could extend toward Ash Shwayrif, where both GNU and eastern-based Libyan National Army militias have mobilized since August. The GNU released late Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi’s son, Saadi Qaddafi, and seven other officials from the former regime in Tripoli on September 5. The GNU is positioned to release Senussi, which could prevent further escalation in Ash Shwayrif.

The Islamic State in Libya (IS-Libya) maintains a limited presence in western Libya but could take advantage of the fighting in Tripoli if clashes continue to escalate. GNU authorities arrested a senior IS-Libya commander in the western Libyan city of Bani Walid on September 7. IS-Libya is most active in southwestern and south-central Libya, but an escalation in militia clashes would reduce the day-to-day security operations in western Libya and could allow IS-Libya to conduct attacks in more populated areas such as Tripoli. IS-Libya has a history of targeting governmental institutions to exacerbate tensions but has not done so for several years.

East Africa

Somalia

A political crisis is escalating in Somalia. Somalia’s president and prime minister are locked in a power struggle over the prime minister’s dismissal of the country’s security chief. Political tensions last spiked in Mogadishu in April, when President Mohammed Abdullahi Farmajo attempted to extend his term. That crisis divided security forces in Mogadishu along clan lines. The renewed political drama threatens the organization of presidential and legislative elections this fall that are meant to avert a constitutional crisis. Unrest in Mogadishu draws security forces away from positions outside of the capital, where they are combating al Shabaab, and creates opportunities for al Shabaab to escalate attacks inside the capital.

Ethiopia

Conflict is worsening the humanitarian crisis in northern Ethiopia. The Ethiopian federal government and its partners—including forces from Eritrea and from Ethiopia’s Amhara regional state—is fighting with forces aligned with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) for control of the Tigray region in northern Ethiopia. The conflict has been ongoing since November 2020 and escalated in late June, when TPLF forces recaptured the Tigray regional capital and advanced outside of Tigray’s borders.

Both sides are now trading accusations of atrocities. Amharan officials accused TPLF forces of killing at least 120 civilians in early September. The accusations follow reports that Sudanese officials recovered bodies of Tigrayan civilians downstream from the conflict zone. Reports of direct attacks on civilians come alongside reports of growing hunger, with the World Food Programme stating that up to 7 million people in northern Ethiopia face acute food shortages. The UN recently accused the Ethiopian government of disrupting the delivery of food aid to the Tigray region.

Mozambique and Tanzania

Islamic State–linked insurgents are retreating southward after losing control of a port in northern Mozambique. Mozambican and Rwandan security forces recaptured a strategic port in northern Mozambique from Islamic State–linked militants on August 8 (Figure 2). Militants have held Mocímboa da Praia since August 2020. Militant attacks continued for two consecutive weeks, starting August 18, south of Mocímboa da Praia.

Mozambican forces captured eight militants near Pequeue on August 18. The militants may have been retreating south ahead of Rwandan-Mozambican operations in Mbau. The troops expelled militants on August 20 and *retook Mbau on August 21, but the area remains contested. Security forces launched operations against militants near Mbau on August 28. Militants also captured and killed 10 fishermen in Mucojo on August 28. Militants maintain the ability to attack security forces in Mocímboa da Praia from both the Nangade and Palma districts to the north.

Figure 2. Key locations in northern Mozambique: September 2021

Source: Kathryn Tyson

A lone gunman who killed three police officers in Tanzania could have connections to the conflict in northern Mozambique, but evidence is limited. The man opened fire in the diplomatic quarter of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on August 25th before police killed him. Local police said the shooter was a terrorist. The Tanzanian inspector general speculated that the attack could be a response to Tanzania’s involvement in the South African Development Community forces in Mozambique (SAMIM). Mozambique’s president announced that SAMIM forces, including Tanzanian troops, arrived in Mozambique on August 9. Tanzania also announced it would *host a new Southern African Development Community counterterrorism center on August 18.

The Islamic State has not claimed responsibility for the attack, but the gunman may have carried out the attack in support of the group. An unofficial Islamic State media outlet promoted the Dar es Salaam attack and encouraged lone wolf attacks on August 25.[1] A pro–Islamic State media platform shared a video on August 28 allegedly showing the Dar es Salaam shooter lip-syncing an Islamic State chant a day before the shooting.[2]

West Africa

Sahel

Salafi-jihadi groups increased attacks on civilians in Mali in the first half of 2021. The UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) released its quarterly report on August 30, covering trends in human rights violations and abuses in Mali from April 1 to June 30. Militants killed, injured, or abducted 527 civilians during this quarter, marking an overall increase of more than 25 percent from the first quarter. Attacks targeting civilians or their property occurred in several towns throughout central Mali (Figure 3). Burkina Faso and Mali announced on September 7 that they will mount joint military operations against Salafi-jihadi groups operating in response to the uptick in attacks.

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) is more prone to targeting civilians and is responsible for some of the most lethal attacks against civilians in the Sahel in recent years, including record-breaking attacks in western Niger. Attributing recent attacks is difficult, however, particularly in northern Burkina Faso, where several Salafi-jihadi groups are active and do not regularly claim attacks. Ansar al Islam, a Burkina Faso–based group loosely aligned with Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), likely conducted an *attack killing 65 civilians and 15 Burkinabe security forces on August 18.

JNIM is also pursuing a strategy of pressure and negotiation to gain control over civilians in central Mali. Members of the Macina Liberation Front (MLF), a JNIM component, struck a *peace agreement with local leaders in central Mali’s Niono Circle on September 3, continuing a trend of negotiated settlements in this area. MLF members have also expanded their presence along the Mauritanian border by *intimidating civilians.

Figure 3. Selected locations of attacks on civilians in Mali: April 1–June 30, 2021

Source: Rahma Bayrakdar

French counterterrorism operations may have killed the leader of ISGS, according to unconfirmed reports. Scattered reports have emerged that French Barkhane forces *killed ISGS Emir Abu Walid al Sahrawi near central Mali’s Menaka Region along the Nigerien border on August 23. Sahrawi founded ISGS and pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in May 2015. Neither French officials nor ISGS have confirmed reports of Sahrawi’s death.

Sahrawi’s death, if confirmed, would likely cause the leadership of ISGS to pass to one of his lieutenants. The leadership change could lead to some shifting in allegiance, particularly since many ISGS leaders are networked with other Salafi-jihadi groups in the Sahel. Sahrawi’s death is unlikely to collapse ISGS or significantly alter its trajectory.

A coup d’état in Guinea may have follow-on effects for counterterrorism efforts in the Sahel. Guinea’s president was ousted in a military coup on September 5. Potential further instability in Guinea would affect counterterrorism efforts in Mali and create vulnerabilities in Guinean territory. Guinea contributes 650 troops to MINUSMA in the Kidal Region in central Mali. Should Guinea recall its troops, security may worsen in Kidal, particularly because Chad—which also supplies forces to MINUSMA in this area—recently announced plans to withdraw 600 troops.

Salafi-jihadi groups may also take advantage of unrest in Guinea to target the country, though Guinea likely remains lower priority for them than other coastal countries such as Côte d’Ivoire and Benin, where militants have become more active. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb leaders *met in February 2020 to discuss the expansion of al Qaeda’s operations beyond Mali to establish a greater foothold in West Africa. JNIM is not yet active in Guinea, but the group’s leader has named Guinea as a target due to its contributions to MINUSMA.[3]

[1] SITE Intelligence Group, “Promoting Attack Near French Embassy in Tanzania, IS-aligned Unit Summons Lone Wolves to Strike,” August 25, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[2] SITE Intelligence Group, “Video Shows Alleged Dar es Salam Shooter Brandishing Gun, Lip-syncing IS Chant,” August 28, 2021, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[3] SITE Intelligence Group, “AQAP-Affiliated Newspaper Interviews Leader of Newly-Formed AQIM Branch in Mali,” April 6, 2017, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.