Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Africa File: Rapid French withdrawal unravels counterterrorism posture in Mali

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

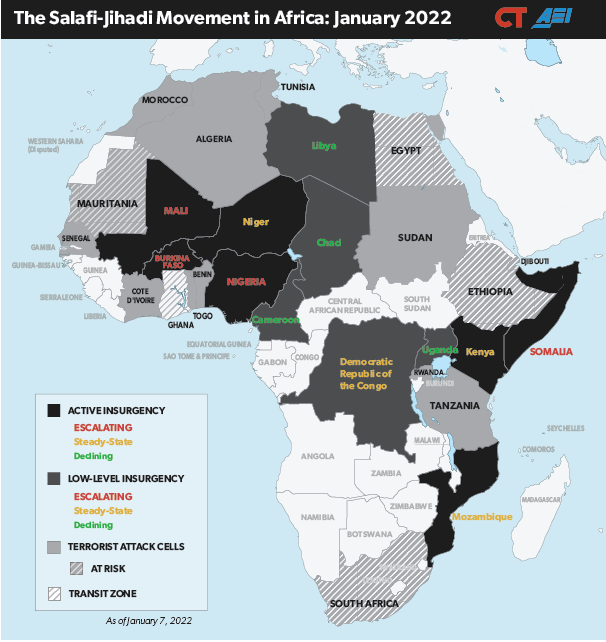

Key Takeaway: French forces are accelerating their withdrawal from Mali following a breakdown in French-Malian relations. The withdrawal will remove necessary support to other local, regional, and international forces in Mali, leading to a drastic reduction in pressure on Salafi-jihadi groups in the Sahel. These groups, particularly al Qaeda’s Sahel branch, will capitalize on this opportunity to establish a secure haven in northern Mali.

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: January 2022

View full map.

Source: Authors and Kathryn Tyson.

France announced its withdrawal from Mali on February 17. France will cease its counterterrorism mission Operation Barkhane in Mali and will remove all forces within six months. About 2,000–2,500 French troops will remain in the Sahel and adopt a “by, with, and through strategy,” supporting local militaries. Some troops will move from Mali to bases in Chad, Niger, and elsewhere in the Sahel, joining about 1,600 French troops already deployed in the Sahel outside of Mali. The European special operations Task Force Takuba will also leave its current bases in Mali and continue operations from Niger and Burkina Faso.

This withdrawal accelerates and expands prior French drawdown plans, announced in July 2021, following a deterioration in French-Malian relations. The Malian military launched two coups in 2020 and 2021, installing a military junta that has become increasingly brazen in its efforts to hold power. The junta’s efforts have also alienated it from many international partners and neighbors. The junta has resisted international and regional calls for a return to democracy, and it announced a five-year election delay in January. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) responded with sanctions and border closures. The French ambassador to Mali called the junta illegitimate, leading to his expulsion. Tensions between Mali and its partners also affected counterterrorism operations after Mali restricted access to its airspace, and European partners criticized the Malian government’s 2021 deal with Russian private military company Wagner Group.

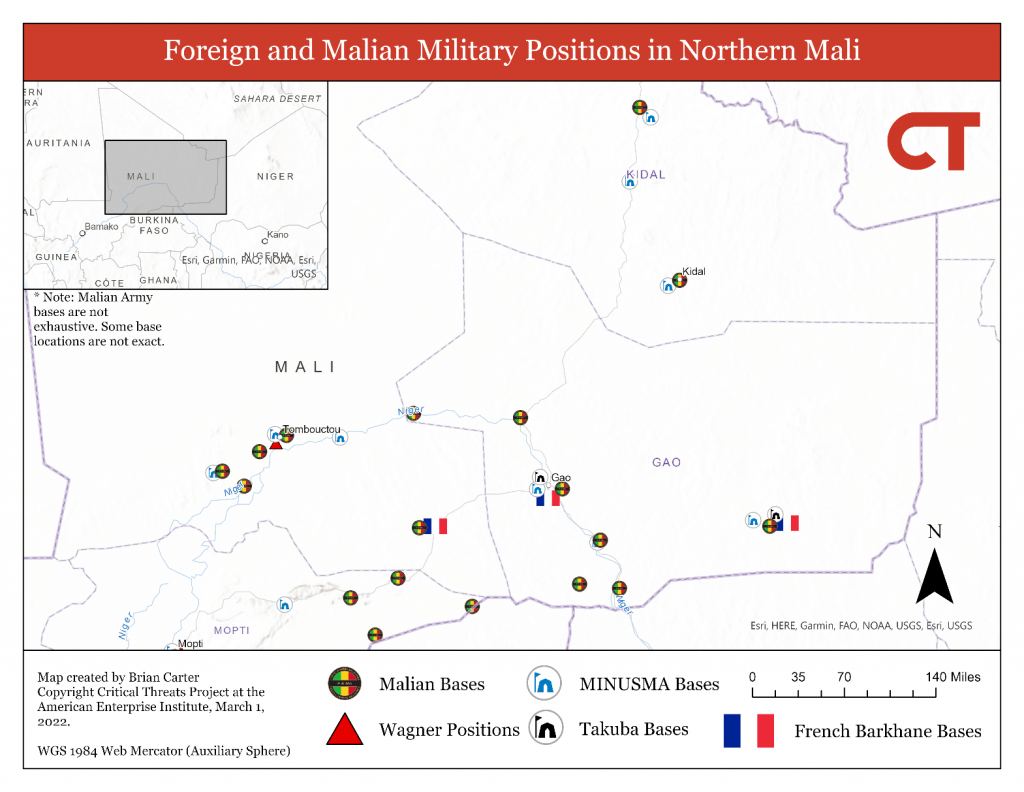

Figure 2. Foreign and Malian Military Positions in Mali

Source: Grey Dynamics, UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, AEI’s Critical Threats Project

The French withdrawal will reduce direct operations targeting Salafi-jihadi groups and deprive local and foreign forces still active in Mali of military and logistical support. Barkhane forces had regularly conducted *raids and airstrikes targeting Salafi-jihadi militants in the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. France will continue such operations inside Niger and Burkina Faso but not in Mali. Barkhane also *provided[1] necessary capabilities that other forces in Mali will struggle to replace. This support includes logistics and *intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR). US troops and platforms mostly based in Niger augment French capabilities.

The French withdrawal will severely degrade the effectiveness and capabilities of the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). UN leaders acknowledge that Barkhane’s withdrawal will impact MINUSMA. Barkhane’s *presence in theater and at MINUSMA bases contributes to force protection, including *limiting Salafi-jihadi groups’ ability to move freely near the bases. Barkhane’s withdrawal may also spur the withdrawal of MINUSMA’s German contingent, which provides drones and ISR.

The EU Training Mission (EUTM) in Mali will likely withdraw following Barkhane’s departure due to force protection and political concerns. EUTM is *unable to move personnel beyond southern Mali without support from MINUSMA and Barkhane. Barkhane *provides quick reaction forces that assist EUTM cadres. The Malian junta has also *restricted foreign forces’ access to its airspace, rendering European forces unable to meet medevac standards.

Barkhane’s withdrawal will compound difficulties facing the Malian Army (FAMA). Barkhane and other partners provide ISR and logistical support to FAMA. FAMA already faces serious supply *difficulties. The combination of Barkhane’s withdrawal and Wagner Group’s presence will likely cause most partners to end ISR cooperation with Mali. France may continue some form of ISR and “operational” support to FAMA post-withdrawal, but the duration of this support is unclear. Intelligence provided by France and its partners will likely be less effective due to a lack of in-country personnel and an overreliance on imagery and drones.

The G5 Sahel Joint Force will face challenges caused by the French withdrawal and Malian political situation. The G5 Sahel alliance comprises Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger. The G5 Sahel *lacks the logistical infrastructure to operate without Barkhane’s support. The G5 Sahel also benefits from EUTM training. Mali may also stop cooperation with the Burkinabe and Nigerien components of the G5 Sahel due to their participation in the ECOWAS sanctions regime targeting Mali.

The French withdrawal will rapidly reduce pressure on Salafi-jihadi groups in Mali. This assessment recognizes Operation Barkhane’s flaws. Operation Barkhane suffers from structural weaknesses and strategic failures and ultimately failed to stabilize the region or prevent Salafi-jihadis’ expansion to new parts of the Sahel. Military-focused counterterrorism missions typically fail to resolve the governance problems and local grievances that drive Salafi-jihadi insurgencies—and can often make them worse. Nonetheless, the rapid withdrawal of Barkhane’s military and logistical capabilities—without the prospect of a better alternative—will provide an acute advantage to Salafi-jihadi groups.

Ending the French mission allows the Malian junta to prioritize its core interests while capitalizing on public frustration with France. The junta will likely prioritize consolidating power and defending its economic interests in southern and central Mali, while delaying a return to democracy. The Malian government historically sees the north as a peripheral security threat managed by negotiating with local actors. The junta will likely aim to address insecurity in the north through negotiations, which would allow the junta to address popular demands to improve security through talks with Salafi-jihadi groups. The junta will also deflect responsibility for follow-on security problems by blaming the instability on France.

Al Qaeda’s Sahel branch will deepen its foothold in northern Mali by pinning down ineffective counterterrorism forces and combining force and negotiations to influence local and national Malian actors. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) will likely target MINUSMA and FAMA to fix these forces in their positions, possibly pressuring them to withdraw if they cannot adequately secure their bases. JNIM will capitalize on its increased freedom of movement to adopt a more overt security and governance-provision role. The group will likely prioritize its efforts in the countryside initially but may gain more ability to operate openly in northern Malian towns as military missions degrade. JNIM will use force to control local populations in combination with co-opting local powerbrokers and supplying governance structures, such as courts.

JNIM may also solidify its position in northern Mali by negotiating with local actors. A likely interlocutor is the High Council for the Unity of Azawad (HCUA), a Tuareg organization formerly linked to Ansar al Din. Ansar al Din is now part of JNIM, and its founder is JNIM’s emir. The HCUA’s founder is reportedly leading efforts to negotiate with JNIM in a framework organized by the Malian government. JNIM and HCUA leaders have a long history of cooperation and competition dating back to the 1990s.[2] The groups continue military cooperation at lower echelons. JNIM could also intimidate some factions into cooperation, including through assassinations.

JNIM may also engage the Malian government in national-level negotiations to secure its position in northern Mali. Mali’s transitional government could seek to maintain popular support by negotiating with JNIM. Mali’s transitional prime minister acknowledged widespread public support for negotiations in July 2021. The Malian government also negotiated with JNIM to secure a high-profile prisoner exchange in October 2020. JNIM’s leaders see the Taliban’s takeover in Afghanistan as a validation of their strategy and will likely attempt to replicate this approach in the Malian context.

JNIM’s competition with the Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS) may also be a vector for JNIM to increase its control over civilian populations. JNIM and ISGS have been competing for influence, including over gold mines and smuggling routes, in the tri-border region. ISGS activity could increase JNIM’s hold over the population if JNIM is able to portray itself as protecting locals from ISGS *massacres.

A secure JNIM haven in northern Mali will benefit Salafi-jihadi networks across North and West Africa. JNIM will use northern Mali as a rear area to support its efforts in central Mali and Burkina Faso. JNIM will also increase its ability to draw in revenue from smuggling and trafficking routes and extorting the population. Salafi-jihadi leaders will be able to operate more easily from Mali with the reduced threat of counterterrorism operations. Interlinkages between Maghreb and Sahel Salafi-jihadi networks also mean that JNIM will be positioned to send fighters, weapons, and money to support future Salafi-jihadi campaigns in North Africa.

[1] For a detailed account of interactions between military missions, see Elin Hellquist and Tua Sandman, “Synergies Between Military Missions in Mali,” Swedish Ministry of Defense, March 2020, https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI-R--4915--SE.

[2] Alexander Thurston, Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local Politics and Rebel Groups (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 114 & 140.