Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Africa File: Stalled negotiations risk military escalation across several African crises

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

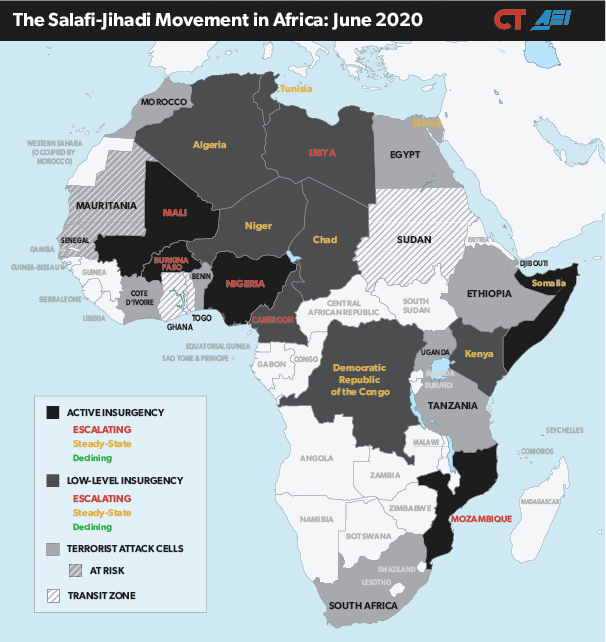

Stalled negotiations across several crises in northern Africa could lead to military escalations that will destabilize or further destabilize states, harm civilian populations, and create new opportunities for the Salafi-jihadi movement to expand.

In Libya, rival forces are preparing to fight for control of the gateway to a key oil-producing region. Russian mercenaries have deployed to oil sites throughout the country, allowing the Kremlin to effectively hold Libya’s oil wealth hostage while positioning itself as a peace broker. Russia and Turkey are both setting conditions to establish long-term military positions in Libya. The risk of conflict between major regional militaries backing Libyan factions, including Turkey and Egypt, remains high.

In Mali, mass protests calling for the president’s resignation will likely resume this week. The government and opposition remain at an impasse following attempted mediation by regional heads of state. The destabilization of southern Mali, if it occurs, would likely draw security resources away from the country’s northern and central regions and strain the French-led counterterrorism mission in the Sahel.

In East Africa, rising domestic tensions in Ethiopia risk destabilizing the state. This unrest may push Ethiopian leaders to take a hard-line stance on filling Ethiopia’s Nile dam, a nationally popular project that is worsening already-tense relations with Egypt and Sudan. In the worst case, the destabilization of Ethiopia would open opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to make inroads in the country. In neighboring Somalia, al Shabaab is positioned to benefit from political turmoil surrounding Somalia’s upcoming elections.

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: June 2020

Source: Author.

Read Further On:

North Africa

West Africa

East Africa

At a Glance: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated August 6, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic will hasten the reduction of global counterterrorism efforts, which had already been rapidly receding as the US shifted its strategic focus to competition with China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. The US administration began withdrawing troops from Afghanistan after signing a peace deal with the Taliban on February 29. The future of US forces in Iraq and Syria is uncertain following the destruction of the Islamic State’s physical caliphate and its leader’s death, though the group already shows signs of recovery. The US Department of Defense is also considering a significant drawdown of US forces engaged in counterterrorism missions in Africa, though support for the French counterterrorism mission in the Sahel has been extended for now.

This drawdown is happening as the Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, continues to make gains in Africa , including in areas where previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement was already positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure before the pandemic hit. Now, a likely wave of instability and government legitimacy crises will create more opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations.

The Salafi-jihadi movement is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali, where al Qaeda–linked militants seek a negotiated settlement with a Malian government under increasingly intense pressure to address political and security crises. Salafi-jihadi insurgencies are also stalemated in Somalia and Nigeria and persisting amid the war in Libya. Conditions in these last three countries favor the Salafi-jihadi movement rather than its opponents in the coming year.

Libya’s civil war, reignited on a large scale in April 2019, will continue to fuel the conditions of a Salafi-jihadi comeback, particularly as foreign actors prolong and heighten the conflict. Counterterrorism efforts in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding in both host and troop-contributing countries and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in their people’s eyes.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command (AFRICOM) is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great-power competition, a move also intended to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness—such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown. COVID-19 has exacerbated existing problems with these forces, with contributing nations reevaluating their commitments to foreign intervention during the pandemic.

The Salafi-jihadi movement has several main centers of activity in Africa: Libya, Mali and its environs, the Lake Chad Basin, the Horn of Africa, and now northern Mozambique. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other places is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse (all now likely to be exacerbated by the pandemic). Local crises are the incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the bases for future attacks against the US and its allies.

North Africa

Libya

The risk of direct confrontation between major regional militaries remains high as Libyan factions and their backers prepare to fight for control of a key city in central Libya. The military preparations focus on Sirte, a coastal city in central Libya that neighbors Libya’s “oil crescent” region, a vital economic location currently controlled by the CORRECTIONA previous version of this brief incorrectly identified LNA as "Libyan National Accord" instead of "Libyan National Army."Libyan National Army (LNA). The LNA is a militia coalition based in eastern Libya and backed by Egypt, Russia, and the UAE. Its opponents are forces aligned with the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), which is based in western Libya and backed by Turkey.

The current phase of the conflict began in April 2019, when LNA forces led by Khalifa Haftar launched an offensive to seize Tripoli, Libya’s capital, from the GNA. The LNA relies heavily on foreign backing, including Russian Wagner Group mercenaries that deployed in fall 2019. The LNA failed to take Tripoli, however, and a subsequent Turkish intervention turned the conflict in the GNA’s favor, ultimately ending the LNA’s campaign to seize the capital in June 2020. Responding to advancing Turkish-backed GNA forces, Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al Sisi declared Egypt’s right to intervene in Libya on June 20 in a bid to enforce a cease-fire that would prevent further LNA losses. Sisi declared Sirte and nearby Jufra air base a “redline.”

The LNA and its backers have escalated efforts to deter a GNA offensive on Sirte and increase leverage in negotiations in late July and early August. The pro-LNA buildup is a response to Turkish-backed forces’ preparations to advance toward Sirte in mid-July. The LNA has *reinforced its position by constructing fortifications and deploying what may be a Russian-made air defense system. Russian and Sudanese mercenaries are also present in the area and have taken control of key oil installations across the country, including Libya’s largest oil field and primary export terminal. Libyan and foreign fighters have also occupied worker housing, seized fuel, and begun to prepare for military activity at oil infrastructure sites in eastern Libya, according to Libya’s National Oil Corporation.

The Kremlin is holding Libya’s oil wealth hostage while positioning itself as a peace broker. Several of the sites occupied by Russian mercenaries are owned by European companies. Wagner Group mercenaries have also been accused of planting land mines in civilian areas and around the occupied oil sites. Russian officials continue to deny the presence of Russian nationals in Libya, however, and publicly emphasize the diplomatic track, including a joint working group formed with Turkey in late July.

Several other diplomatic initiatives are underway. The US is pursuing “360 degree diplomatic engagement” and has focused in Russian support for the LNA’s oil blockade, including reportedly threatening sanctions against LNA commander Haftar. The leaders of rival Libyan legislative bodies also attended separate negotiations in Morocco.

Military courts continue to crack down on civil liberties in LNA-controlled eastern Libya. A military court sentenced a photojournalist to 15 years imprisonment on “vague” terrorism charges in a secret trial in late July. The journalist may have been targeted because his videos were shared by a Turkish-affiliated channel.

Forecast: In the most likely case, fighting will stalemate in central Libya. Egypt may make a show of force to persuade Turkey to scale back its support, limiting the advance of GNA-aligned forces and preserving LNA control of the oil crescent. This de facto partition would likely lead to future rounds of civil war and proxy conflict after the combatants rearm. The presence of Russian forces at oil sites makes a negotiated settlement more likely in the near term and sets conditions for a long-term Russian military presence in Libya.

In a less likely but more dangerous case, a miscalculation or error could draw external forces into direct conflict, possibly including conflict between two US allies (NATO ally Turkey and major non-NATO ally Egypt). This fighting would be more deadly than previous bouts in Libya due to the introduction of more forces and increasingly advanced weaponry.

Either case preserves and worsens the conditions that allow Salafi-jihadi groups to strengthen. The Islamic State will likely continue its renewed attack tempo and may resume intermittent attacks targeting symbolic state institutions in coastal cities in the coming months. (Updated August 6, 2020)

Tunisia

Tunisia’s president appointed a new prime minister who must now form a government amid a political crisis and widespread dissatisfaction with the government. Tunisia will again begin forming a new government under independent Prime Minister–designate Hichem Mechichi just five months after former Prime Minister Elyes Fakhfakh took office. Fakhfakh, who formed a government in February after months of political deadlock, resigned after corruption allegations and tensions with other political parties led to a majority vote of no confidence.

Mechichi must now form a government within a month to avoid the dissolution of parliament and new elections. Elections could be a flash point as Tunisia grapples with instability rooted in economic dissatisfaction. Police and protesters clashed in June after the arrest of an activist amid intense economic protests. Tunisia’s economy suffers from high unemployment, inflation, and living costs, which the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated.

West Africa

The Western Sahel

The political crisis will continue destabilizing Mali in the near future as negotiations between the opposition and Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta stall. Protests calling for Keïta’s resignation have gripped the country’s capital, Bamako, since early June. The protests are in response to economic problems, perceived government corruption, and failure to contain a burgeoning Salafi-jihadi insurgency, which disrupted legislative elections earlier in 2020. The opposition leader, Mahmoud Dicko, is a prominent imam and former ally of Keïta who rose to prominence as an advocate for public morality and has acted as an intermediary in prior negotiations with Salafi-jihadi groups in northern Mali.

Regional leaders have attempted to broker a deal between Keïta and the opposition, including proposing a unity government in which Keïta would govern jointly with opposition leaders. The opposition movement rejected the proposed plan in late July. Opposition leadership has continued to demand Keïta’s resignation and have reiterated their refusal to cease protests until Keïta steps down.

Protests have resumed, albeit at a smaller scale, since a “truce” for the Eid al Adha holiday at the end of July. Police crackdowns on protesters also appear to have lessened. Large protests, and potentially crackdowns, will likely resume following opposition calls for civil disobedience on August 3 and a strategic meeting between opposition leaders on August 4.

The political crisis poses several challenges to Mali’s security. The use of anti-terrorism forces against protesters risks delegitimizing the government and creating opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to attack in Bamako while anti-terrorism forces are preoccupied. While Salafi-jihadi groups have not focused on attacking Bamako or other Sahelian capitals in recent years, instability could create new opportunities and incentives for such attacks.

Any major instability in the capital region could also draw the Malian military away from northern and central Mali. Malian military forces have participated in several large-scale counterterrorism operations this year. Redeployments, if they occur, would lessen pressure on Salafi-jihadi groups that seek to dismantle and replace local governance structures.

Jama'at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), the al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb affiliate in the Sahel, claimed several attacks in central Mali in early August. Suspected JNIM militants killed five soldiers in twin attacks on military convoys in the Segou province in central Mali on August 2. Suspected JNIM militants killed five soldiers in twin *attacks in Niono Cercle, Segou, Mali on the same day. Separately, intra-jihadist tensions between JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) continued in central Mali. ISGS claimed killing dozens of JNIM militants in central Mali on July 28 following reports of JNIM *killing 14 ISGS fighters in the same attack.[i]

Forecast: Mali’s political crisis will likely continue to destabilize the country through the end of the summer but will not escalate to a military coup or government collapse. The government and opposition will likely arrive at a settlement after several rounds of negotiations. The opposition will likely continue to push for concessions and call for demonstrations, but opposition leaders have an interest in maintaining stability throughout the country and have pushed back against more violent demonstrations. This indicates that while a solution to the crisis may be far off, all parties involved seek to minimize its effects on stability and security throughout the country and have an interest in finding a resolution through more diplomatic means. The president’s resignation would deescalate the situation in the near term but risks long-term damage to Mali’s democratic process.

The national political crisis will lead to negotiations between the Malian government—either the Keita administration or a successor—and JNIM.

In a less likely but more dangerous case, the situation could deteriorate, particularly if the government overreacts with a large-scale crackdown on protesters. Severe instability in Bamako would reverberate throughout the country, including by drawing security resources away from counterterrorism efforts and generating more freedom of movement for Salafi-jihadi groups that would in turn seek to advance toward the capital.

Salafi-jihadi groups will begin to establish governing institutions—such as courts—in the Burkinabe-Malian-Nigerien tri-border area, though they may mask these efforts to facilitate a deal with the Malian government. (Updated August 6, 2020)

Lake Chad

The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) is challenging governance in several states in the Lake Chad Basin. ISWA is increasing the frequency of cross-border attacks into Cameroon from its positions in northeastern Nigeria. ISWA is likely responsible for a grenade attack on a refugee camp in Cameroon’s Far North region on August 1 and has begun attacking Cameroonian military posts along the Nigerian-Cameroonian border. The group claimed three attacks on military posts in the Far North region since the end of May.

ISWA has also begun attacking military convoys and posts in western Chad since early July. This uptick in attacks against military personnel in Chad and Cameroon indicates that ISWA is seeking to expand its area of operations and gain access to new safe havens and resources.

ISWA is also asserting control over major roads in Borno State in northeastern Nigeria to isolate local communities from governmental support and deter military patrolling in the region. ISWA has conducted three *attacks on the Maiduguri-Monguno road against military, aid, and governmental convoys since mid-July.

Militants also attacked several military and aid convoys traveling along the Maiduguri-Damboa road in Borno State. These recent attacks indicate ISWA is seeking to consolidate control of northeastern Nigeria and prevent security, food, and medical assistance from reaching local populations. This isolation is intended to create a reliance on ISWA, allowing the group to consolidate its control over the local population.

Forecast: ISWA will continue its frequency of attacks to deter security forces and establish a zone of de facto control that crosses national borders. (Updated August 6, 2020)

East Africa

The al Shabaab insurgency in Somalia is largely stalemated, but conditions—including political instability and the planned withdrawal of African Union peacekeeping forces—are evolving in al Shabaab’s favor. Severe unrest in neighboring Ethiopia could also create opportunities for al Shabaab and the Islamic State in Somalia, which plotted attacks targeting Ethiopia in 2019.

Somalia

Al Shabaab could take advantage of a potential political crisis surrounding Somalia’s upcoming elections. Somalia’s parliament voted* on July 25 to oust Somali Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire. Khaire was leading negotiations between the Somali Federal Government (SFG) and federal member states to establish a time line for timely national elections at the time of the vote. SFG officials are seeking to delay elections to 2021, while most federal member states want the elections conducted before the end of 2020. The president of Puntland State said* that the no confidence vote was illegal and that Khaire’s removal would derail electoral negotiations. He also accused Somali President Mohammed Farmajo of orchestrating the vote to force electoral delays and extend the presidential term of office. An internet freedom watchdog group reported that a widespread internet blackout* centered on Somalia’s capital Mogadishu followed the vote of no confidence. Officials from the European Union, the US Embassy in Somalia, and the UN released statements criticizing the vote as unconstitutional and illegal.

Negotiators from the SFG and federal member states are scheduled to meet in Dhusamareb in central Somalia’s Galgudud region on August 15. Al Shabaab could conduct attacks targeting this meeting to disrupt the electoral negotiations and exploit social unrest caused by delayed elections.

Forecast: Upcoming electoral negotiations between the SFG and federal member states on August 15 will be unproductive. Popular protests against stalled elections will be met by government crackdowns that could escalate into violence. Al Shabaab will use popular protests as an opportunity to recruit anti-government fighters and call for attacks targeting Somali government officials. (Updated August 6, 2020)

The Islamic State (IS) in Somalia has recruited foreign fighters from South Asia. IS Somalia confirmed* the death of a Pakistani foreign fighter on August 3. A Puntland State security forces raid supported by a AFRICOM air strike killed the militant near Timirshe in northern Somalia's Bari region on July 21. Puntland State officials claimed the operation killed a senior foreign fighter who had served as a trainer and liaison between IS Somalia and other IS affiliates since 2014.

Most IS Somalia foreign fighters are ethnic Somalis from Western countries or the Horn of Africa. The militant’s presence may indicate that IS Somalia can recruit foreign fighters due to ease of travel and limited military pressure compared to other IS areas of operation.

Al Shabaab is waging an information operation to attempt to discredit AFRICOM’s air strike campaign in Somalia and weaken domestic support for the SFG. AFRICOM conducted an air strike killing one al Shabaab militant in the al Shabaab stronghold of Jilib in southwestern Somalia’s Middle Jubba region on July 29. Al Shabaab’s Shahada news agency accused AFRICOM of killing three teenage civilians in the strike.[ii]

The strike occurred one day after AFRICOM confirmed four civilian casualties from an air strike in early February in its second civilian casualty report. The report disputed and directly debunked past al Shabaab accusations. Al Shabaab propaganda accuses the SFG of complicity in the alleged deaths for cooperating with AFRICOM against al Shabaab. Al Shabaab’s goal is to promote popular protests against both US air strikes in Somalia and the SFG.

Ethiopia

Al Shabaab is using historical tensions between Somalia and Ethiopia to justify increasing attacks targeting Ethiopian soldiers in Somalia. Al Shabaab’s al Kata’ib Media Foundation published on August 2 the first in a series of videos exploring the history of Somali-Ethiopian tensions.[iii] The documentary called for its followers to be inspired by a 16th-century Somali Muslim general who conquered most of Ethiopia.

The video also highlighted the defeat of European soldiers sent to assist Ethiopia against the invading Muslim forces. It argued that Ethiopia’s Orthodox Christian roots makes it the “archenemy of Islam” and that Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has secret plans to annex all of Somalia.

Al Shabaab militants attacked an Ethiopian National Defense Force base near Halgan in south central Somalia’s Hiraan region on July 18. African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and non-AMISOM Ethiopian forces are stationed in southwestern Somalia’s Gedo and Hiraan regions. Al Shabaab is likely planning to escalate attacks targeting Ethiopian forces in Somalia and hopes to inspire potential recruits among Ethiopia’s ethnic Somali population.

Alternately, al Shabaab propaganda targeting Ethiopia may be timed to exploit rising tensions between Muslim and Christian communities in the country. Confessional violence broke out between Muslims and Christians in Ethiopia’s Oromia region in mid-July as social tensions spiked following the murder of a popular Oromo singer.

A fraught political transition and the prime minister’s ambitious reform program have inflamed deep ethnic fissures in Ethiopian society, including within his own Oromo community. Protests, riots, and violent government crackdowns could destabilize the state and spread to ethnic Somali communities in southern Ethiopia, opening opportunities for al Shabaab to exploit local grievances and expand into the East African powerhouse.

Tensions between Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt surrounding Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Nile River could escalate if ongoing negotiations stall. Decade-long talks to resolve the dispute resumed* on August 3. The negotiations stalled the next day after Sudanese and Egyptian officials expressed displeasure at Ethiopia’s latest proposed deal. Ethiopian officials argue that the GERD will provide much needed electrification to their country and will not threaten access to fresh water for Egypt and Sudan. Egyptian and Sudanese officials see the dam as an existential threat to their populations. Satellite images from mid-July showed rising water levels in the dam’s reservoir, leading to accusations from Egypt and Sudan that Ethiopia had begun filling the dam without a tripartite agreement. Failed negotiations would lead to bellicose rhetoric from Egypt that could result in a military incident between Ethiopia and Egypt.

The GERD has become an increasingly nationalist issue in Ethiopia. Tens of thousands of Ethiopians joined a government-backed rally on August 2, praising the first stage of the dam’s filling.

Forecast: Domestic strife in Ethiopia will encourage officials to take a hard-line stance on the GERD’s filling, and Ethiopia will continue filling the GERD’s reservoir without any agreement with Egypt and Sudan. (Updated August 6, 2020)

[i] “In Clashes with JNIM Fighters in Gao, ISWAP Claims Inflicting Dozens of Casualties,” SITE Intelligence Group, August 2, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[ii] “Shabaab Reports 3 Children Killed in U.S. Drone Strike, Vilifies American for Ongoing ‘Immoral’ War,” SITE Intelligence Group, July 30, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[iii] “Shabaab Explores History of Somalia-Ethiopia Conflict in Part 1 of Video Documentary,” SITE Intelligence Group, August 3, 2020, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.