Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Africa File: Malian Army Abuses Will Strengthen Salafi-Jihadis in Central Mali

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Key Takeaway: The Malian Army launched a campaign of collective punishment in a bid to reimpose state control in central Mali. This approach, which Wagner Group is enabling, will strengthen al Qaeda’s Mali branch by forcing vulnerable civilian populations to rely on Salafi-jihadi militants for self-defense. Militants may conduct terror attacks in urban areas in retaliation for the central Mali campaign. This campaign also risks inflaming inter-ethnic conflict in central Mali that would inflict widespread harm on civilians.

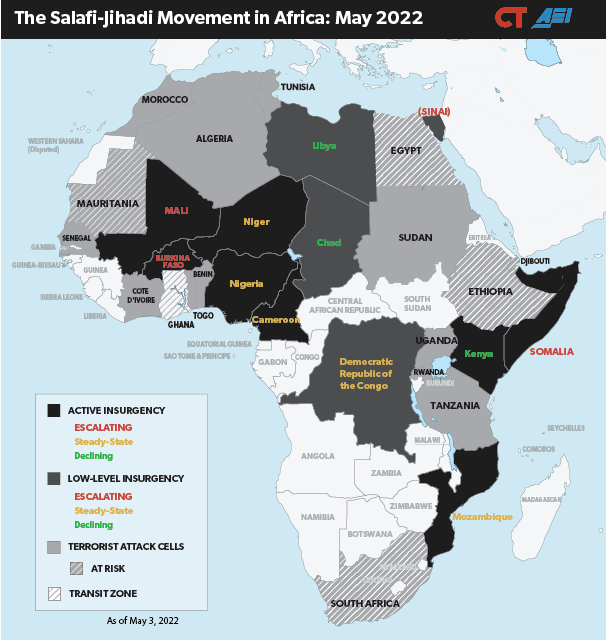

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: May 2022

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

The Malian Army (FAMA) launched a campaign of collective punishment in a bid to reimpose state control in central Mali. The state is largely absent from this resource-constrained region, where competing ethnic-based self-defense groups and Salafi-jihadi groups have fueled a retaliatory violence cycle in recent years. Al Qaeda’s Sahel branch, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), recruits from the local Fulani population by promoting itself as the only viable ally against ethnic militias and state security forces known for human rights abuses. FAMA launched Operation Keletigui in *December 2021 to *“search for and destroy” JNIM and its “sanctuaries” in central and southern Mali. This operation uses quick reaction raids, artillery, and helicopter gunships to reassert FAMA’s presence in central Mali. FAMA is retaliating against JNIM by attacking villages the Malian government claims are JNIM strongholds.

FAMA has partnered with the Russian Wagner Group to conduct this campaign. The Wagner Group is a Kremlin-supported network of military companies financed by a close personal ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin that is used to achieve Russian goals around the world, including in Africa. Mali’s current government, which took power in a 2021 coup, established its partnership with Wagner while downgrading its long-standing defense partnership with France. French forces escalated a planned withdrawal from Mali in 2021 due to deteriorating relations with the Malian junta, ending a decade-long counterterrorism presence in the country. The Malian government nullified the Franco-Malian status of forces and defense cooperation agreements on May 2. Germany announced the end of its participation in the EU Training Mission in Mali on May 4.

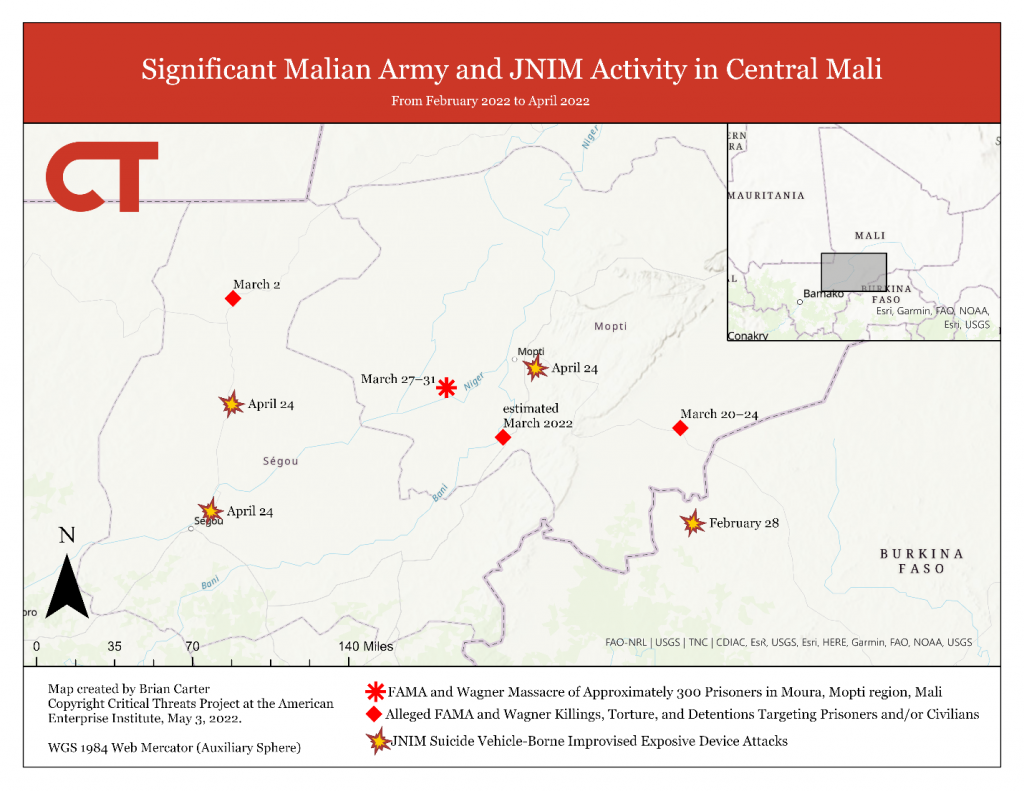

The French and European drawdown coincides with a new, and newly brutal, FAMA approach to security in central Mali. Wagner and the FAMA committed several acts of collective punishment in central Mali against Fulani civilians in April. FAMA and Wagner summarily executed at least 300 Fulani prisoners in a massacre in Moura in late March. FAMA portrays these missions as targeted, *intelligence-based raids killing large numbers of “terrorists.”

JNIM is capitalizing on the brutality and weakness of the FAMA-Wagner campaign by strengthening ties to vulnerable populations in affected areas. FAMA and the Wagner Group have not attempted to hold villages after their “counterterrorism raids” and likely lack the manpower and capability to do so. JNIM therefore reimposes its control after security forces depart. JNIM will improve its legitimacy by presenting itself as the only available security guarantor for local populations. The group conducted three suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device attacks targeting FAMA bases on April 24. JNIM also retaliated by kidnapping a Wagner contractor in early April, calling Wagner a “criminal force” that killed “hundreds of defenseless innocents,” a reference to the late March Moura massacre. JNIM also threatened additional attacks against the *Malian government.

Figure 2. Significant Malian Army and JNIM Activity in Central Mali, February–April 2022

Source: AEI’s Critical Threats Project.

In the most likely scenario, JNIM will expand its control zones in central Mali and may begin an attack campaign in urban areas, potentially expanding instability to other parts of the country. JNIM’s role as a security guarantor for vulnerable populations will allow it to solidify its control zones, increasing its freedom of movement and the logistical support it receives from the population. Security forces and local militias could heighten violence by retaliating against communities perceived to be supporting JNIM cells. This cyclical violence will severely affect civilian populations, increasing local armed mobilization on all sides.

Enhanced logistical support and freedom of movement may allow JNIM to continue developing its capabilities and conduct a greater number of complex attacks. JNIM has developed its vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) capabilities over recent years, most recently employing VBIEDs in June 2021 and February 2022 before its recent April attack. Greater freedom of movement will allow JNIM to expand its attack zone toward the capital region, particularly given preexisting activity in the Koulikoro region northeast of Bamako.

JNIM may be planning attacks targeting Bamako or other major cities. A JNIM leader *called on the government to “prepare for the . . . real fights,” and on April 25 claimed JNIM cells are active in Mali’s major cities. The US Embassy in Mali warned on April 29 of a possible terrorist attack targeting Bamako between April 30 and May 1. New attacks in Bamako would indicate a resumed JNIM capability to carry out attacks in urban zones. French Operation Barkhane likely degraded JNIM’s capability to conduct large attacks in Bamako by eliminating key cell leaders. Malian security services *arrested two JNIM fighters in Bamako in March 2021. Capability losses likely contributed to some of this shift away from terror attacks, but JNIM likely also de-emphasized terror attacks for strategic reasons. JNIM leaders likely recognized high-profile attacks or conquests triggered strong Western responses that threatened their progress toward local goals, mirroring a larger trend toward prioritizing local gains across the al Qaeda network.

Attacks in Bamako or against military bases would threaten the Malian military junta’s legitimacy with its core constituencies in Bamako by affecting the safety of populations in major cities and demonstrating Mali’s deteriorating security. JNIM attacks causing high military casualties may also threaten the government by *spurring protests among soldiers’ family members.

In a worst-case scenario, continued intercommunal conflict may cause widespread, armed communal mobilization in central Mali and trigger a descent into ethnic cleansing. Ethnic self-defense militias began to mobilize in 2016 in response to Salafi-jihadi violence and a lack of state support, beginning a cyclical pattern of tit-for-tat violence between Salafi-jihadi groups and self-defense militias. This violence included large-scale massacres targeting civilians based on ethnicity.

FAMA’s actions risk stoking and expanding ethnic-based violence. The Malian state has backed self-defense groups to a degree, though the extent of this cooperation remains unclear. The Malian government and Dan Na Ambassagou, a Dogon ethnic militia, reportedly *agreed to a security and counterterrorism plan in central Mali in 2020. FAMA also collaborated with Dan Na Ambassagou “closely” through 2018, and the Malian Defense Ministry encouraged youth to join FAMA and “responsible self-defense groups” in January 2022. FAMA’s current campaign also broadly demonizes Fulani as terrorists, feeding into existing prejudices among other ethnic groups that equate Fulani identity with JNIM membership. JNIM’s central Mali branch has fed this dynamic by recruiting Fulani members and targeting Dogon militias and other ethnically aligned armed groups, even while JNIM as an organization officially denies leveraging ethnicity and presents its leadership as a solution to ethnic strife.

FAMA and JNIM actions risk raising the level of ethnicity-based violence in central Mali from intermittent to systemic. Self-defense groups have previously mobilized at the village level. Ongoing conflict, worsened by the FAMA campaign, could cause Fulani militias to form and mobilize above this level, likely in partnership with JNIM’s central Mali component. Non-Fulani ethnic armed groups will also mobilize because FAMA lacks the capability to provide security. Widespread and organized armed communal mobilization beyond a local level would significantly raise the likelihood of mass atrocities, including the large-scale killing of civilians based on ethnicity.