Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Africa File: Salafi-Jihadi Groups May Exploit Local Grievances to Expand in West Africa’s Gulf of Guinea

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Key Takeaway: Salafi-jihadi groups are beginning to intensify attacks in the northern border regions of several Gulf of Guinea states. These attacks may indicate that al Qaeda–linked militants intend to extend their territorial insurgency to these countries, continuing a multiyear southward expansion in West Africa.

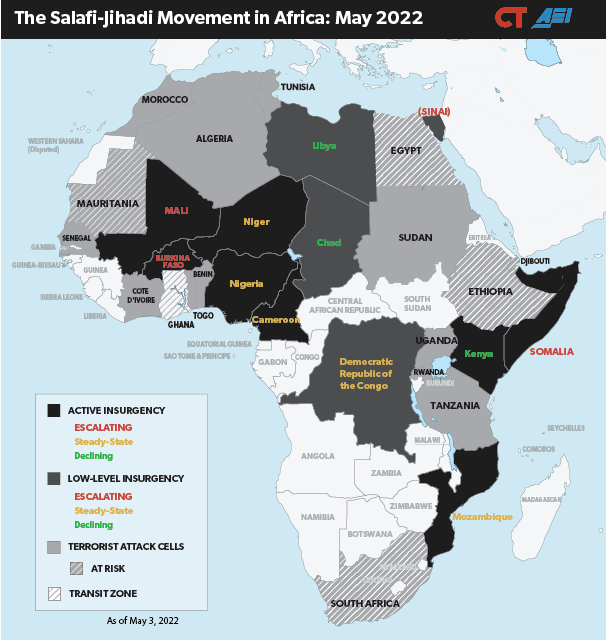

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: May 2022

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

Salafi-jihadi militants conducted the second attack targeting security forces in northern Togo since November 2021. Al Qaeda’s Sahel affiliate, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), likely carried out both attacks. Around 60 militants briefly *overran a Togolese base in Kpinkankandi in northern Togo on May 10–11, killing eight Togolese soldiers and wounding 13 more. Likely JNIM militants first *attacked a Togolese military post in Kpendjal prefecture in northern Togo in November 2021.

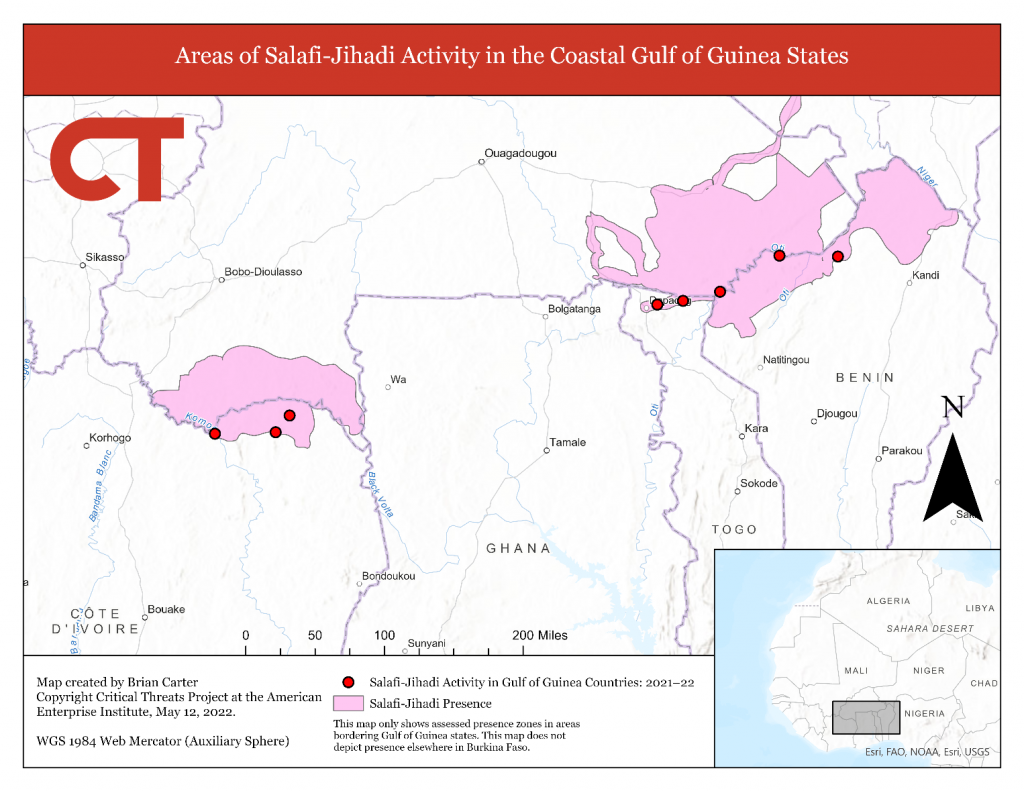

Salafi-jihadi groups have previously used Benin and Togo to procure supplies but now may be conducting offensive attacks. JNIM and other Salafi-jihadi groups have been using border areas of Gulf of Guinea countries, particularly Benin, Ghana, and Togo, to source motorcycles, basic goods, weapons, and money in recent years, including by capitalizing on trafficking and criminal networks. JNIM and the Islamic State’s Sahel Province control local supply lines from sanctuaries in the W-Arly-Pendjari Park Complex straddling the Burkinabe-Beninese-Nigerien tri-border region. Salafi-jihadi militants’ freedom of movement in parts of Burkina Faso allows them to make repeated incursions into neighboring Gulf of Guinea states and evade pressure from security forces on either side of the border.

JNIM activities in Benin and Togo in 2021 and 2022 indicate that the group is attempting to capitalize on local grievances to recruit and is now more willing to challenge local security forces directly. Likely JNIM militants began using roadside improvised explosive devices and small arms to target Beninese security forces in December 2021. These attacks may be responses to stepped-up security force efforts to target smuggling and disrupt JNIM activity. Benin faces the same localized farmer-herder violence that has driven the expansion of Salafi-jihadi groups elsewhere in the Sahel, creating a risk for radicalization particularly if Salafi-jihadi groups can make common cause with local interest groups against the state and security forces. Beninese and Togolese security forces have relatively positive relations with the local population, however, providing some insulation against this risk. Beninese security forces regularly arrest those responsible for communal violence targeting pastoralist communities, demonstrating their ability to protect locals.

Cote d’Ivoire has not experienced a recent change in Salafi-jihadi activity but faces greater risk because of popular grievances and poor relationships between local populations and the state. JNIM has historically targeted Cote d’Ivoire as revenge after Ivorian participation in joint counterterrorism operations in other Sahel countries. JNIM conducted a major attack on a hotel in the Ivorian capital Abidjan in 2016. JNIM targeted Ivorian security forces in northern Cote d’Ivoire in 2021 and 2022, sometimes in retaliation for counterterrorism operations. A JNIM subgroup operates in the Ivorian-Burkinabe border region, where joint Burkinabe-Ivorian operations have been so far unable to dislodge it. JNIM may also be capable of expanding its presence by recruiting from disaffected Ivorians stigmatized by other communities and the security forces. Intercommunal relations in northern Cote d’Ivoire are tense and rooted in farmer-herder conflict. These grievances, including the state’s mishandling of its response, create an opportunity for JNIM to recruit among Ivorian herders. Security forces and sedentary farmers sometimes arrest Fulani civilians indiscriminately, stigmatizing them and equating pastoral communities with criminal activity and jihadist groups.

Figure 2. Areas of Salafi-Jihadi Activity in the Coastal Gulf of Guinea States

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute.

JNIM has recruited at least some Ghanaians and likely transits personnel through Ghana. Ghana is at high risk for JNIM recruitment of Ghanaians from nomadic Fulani communities, which often struggle to prove their citizenship in Ghana. Intercommunal farmer-herder conflict driven by local grievances and banditry is already occurring in northern Ghana. Ghanaian security forces have carried out multiple security operations in northern Ghana aimed at stemming violence and banditry. A Ghanaian Fulani JNIM member conducted a suicide attack on a French military base in Gossi, Mali, in June 2021. There has so far been no confirmed JNIM activity in Ghana.

JNIM’s expanding freedom of movement in Mali increases its ability to operate in other West African littoral states. JNIM likely smuggle goods and raises money in the Senegalese-Malian border region. JNIM may seek to access illicit money flows from gold mines in Senegal and western Mali’s Kayes region. Senegalese security forces *dismantled a JNIM cell in Senegal in January 2021. JNIM also contests areas in northeastern Kayes region, where JNIM has previously conducted *attacks near the Senegalese and Mauritanian borders.

JNIM may also pose a growing threat to Guinea. Salafi-jihadi groups have not previously attacked in Guinea, but militants have operated in the country. Guinean security forces have arrested al Qaeda–affiliated individuals, including a US-designated *terrorist in 2016. JNIM is rebuilding its presence in Sikasso region in southern Mali, bordering Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, and Guinea. A JNIM brigade formerly active in Sikasso may have resumed activity in recent years.

Salafi-jihadi activity will likely remain limited in the Gulf of Guinea states’ northern border areas unless local governance conditions deteriorate significantly. JNIM and its ilk have expanded in the Sahel in areas already afflicted by poor governance and intercommunal conflict. Salafi-jihadi militants lack the same degree of influence and force projection in West African littoral states and will face demographic limits on any potential insurgency. They could gain a larger foothold in a worst-case scenario of civil war or societal breakdown in an at-risk border region, however. Littoral states and their international backers should prioritize governance-building approaches to remove opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to recruit from and operate among aggrieved populations. An overly securitized policy that further demonized whole communities risks forcing vulnerable groups to partner with Salafi-jihadi groups for survival.

On their current trajectory, Salafi-jihadi groups have significant opportunities to expand their influence and activities in West Africa’s littoral states. Security in Mali and Burkina Faso will likely continue to deteriorate, giving militants secure havens from which to project force into the West African littorals and gradually increase their sway over local communities. Attacks in the northern regions of the Gulf of Guinea states may also seek to dissuade them from participating in joint counterterrorism operations in Burkina Faso or Mali. Salafi-jihadi groups could also resume attacking foreign targets in littoral West Africa, continuing a long-running effort to remove Western influence from the region.