Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.

The rapid destabilization of the western Sahel is escalating a humanitarian crisis and allowing Salafi-jihadi groups to strengthen. A sharp uptick in violence in Burkina Faso has displaced nearly half a million people and placed ten of thousands in need of urgent aid. This crisis is caused in part by the spread of Salafi-jihadi groups linked to al Qaeda and the Islamic State, which are growing increasingly lethal. Recent counterinsurgency operations by French and local forces disrupted Salafi-jihadi groups for the short term but are unlikely to have a lasting effect as governance and security conditions continue to deteriorate.

The Sahel’s problems will not remain isolated from the US and Europe forever. Salafi-jihadi groups in the Sahel are “practicing locally for a global jihad” and will ultimately bring their capabilities to bear in other theaters. Another mass migration wave, akin to those that have already politically destabilized Europe, is also highly probable.

The destabilization of the Sahel’s northern neighbors makes these worse cases more likely. Algeria, typically a stable bastion in a tumultuous region, faces a government legitimacy crisis that its December 12 elections will not solve. Many outcomes are possible, including the short-term weakening of the protest movement, but political turmoil and unrest remain likely without meaningful reforms.

Neighboring Libya remains mired in the conflict that has made it a hub for irregular migration and a haven for Salafi-jihadi groups. The US has intensified diplomatic efforts to resolve the latest bout of the country’s civil war, but subsequent military escalations and the continued involvement of multiple foreign actors indicates the conflict will likely continue. The fighting is causing increasing civilian harm and allowing Salafi-jihadi groups to regain freedom of movement in unstable areas.

Read Further On:

At a Glance: The Salafi-Jihadi Threat in Africa

Updated December 3, 2019

Global counterterrorism efforts are rapidly receding as the global counter–Islamic State coalition contemplates its next steps after destroying the Islamic State’s territorial caliphate and the US shifts its strategic focus to great power competition. The US returned to counter–Islamic State operations in Syria in late November 2019 after an abortive withdrawal in October. Indicators of the Islamic State’s return are apparent in both Iraq and Syria, however, even as the group recovers from the death of its leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and other senior officials in late October.

The US withdrawal damaged America’s reputation with current and potential counterterrorism partners and the future of US engagement in Syria remains in doubt. The US administration also seeks to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan, a course that will likely be delayed rather than altered by the breakdown of talks with the Taliban. However, the Salafi-jihadi movement continues to make gains in Africa, including in areas in which previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement is positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations.

The Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, on the counteroffensive in Libya, and stalemated in Mali, Somalia, and Nigeria. However, conditions in these last three countries favor the Salafi-jihadi movement rather than its opponents over the next 12–18 months.

Libya’s civil war, reignited on a large scale in April, will continue to fuel the Salafi-jihadi comeback, possibly allowing the Islamic State or al Qaeda to regain some of the territory they controlled before major operations against them from 2016 to 2019. The Islamic State’s comeback in Libya is part of its global effort to reconstitute capabilities after military defeats, an effort that the group’s late leader, Baghdadi, sought to galvanize in a September audio message. Stalemates in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding in both host and troop-contributing countries, and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in their people’s eyes.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great power competition, a move also intended to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness — such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown. French exhortations in the wake of the death of 13 French commandos in Mali in late November may increase European support for the G5 Sahel in the near term.

The Salafi-jihadi movement currently has four main centers of activity in Africa: Libya, Mali and its environs, the Horn of Africa, and the Lake Chad Basin. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other place is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse. Local crises are the incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the bases for future attacks against the US and its allies.

West Africa

Mali and Burkina Faso

The Salafi-jihadi movement is expanding more rapidly in the western Sahel than in any other African region as communal violence and state fragility spread. The movement’s historical epicenter in this region is Mali. Salafi-jihadi groups are active in the country’s north and have spread to the country’s center, where ethnic-based violence has increased in the past two years. However, the crisis’ epicenter may be shifting to neighboring Burkina Faso, where Salafi-jihadi attacks are rapidly destabilizing the country’s north and east. The violence has displaced hundreds of thousands of people and left 2.4 million in need of emergency food assistance. Salafi-jihadi groups seek to drive out security forces and establish themselves as the de facto governing power in parts of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

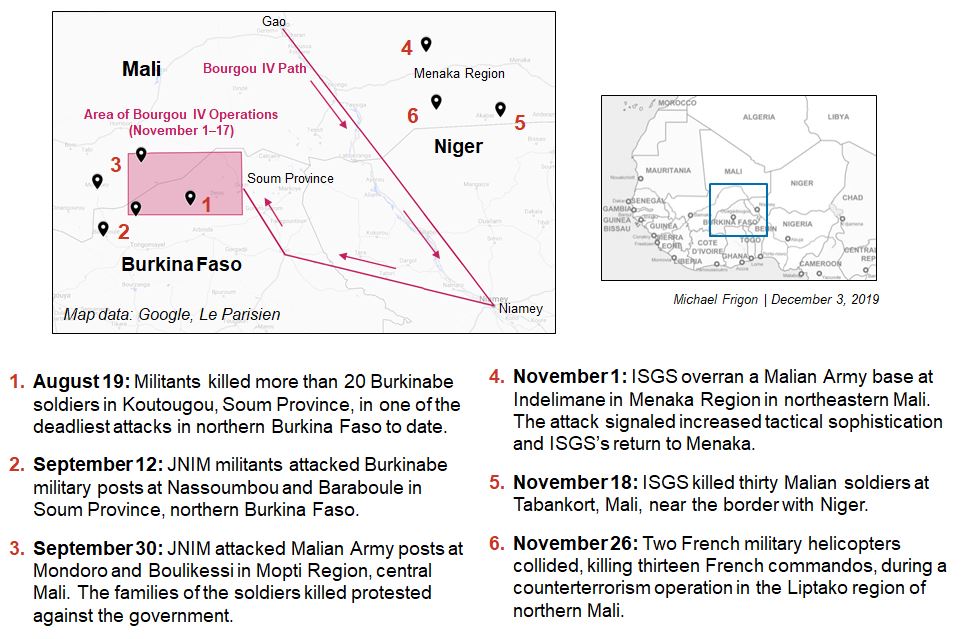

A joint operation by Sahel countries and France disrupted Salafi-jihadi groups in Mali and Burkina Faso but will likely have only short-term effects. The operation, Bourgou IV, was a response to an uptick in large-scale attacks by Salafi-jihadi groups in the tri-border region of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. The unprecedented operation, which involved 1,400 French, Malian, Burkinabe, and Nigerien troops, sought to neutralize Salafi-jihadi logistics and communications capabilities from November 1–17. Troops also reinforced the Malian military camp at Boulikessi, the site of a recent major attack.

Operation Bourgou IV is one of several military responses to major Salafi-jihadi attacks in recent months. The Malian Army withdrew from isolated camps near the Niger and Burkina Faso borders and launched a counteroffensive against Salafi-jihadi groups in central Mali in recent weeks. The Burkinabe military has increased public partnership with French forces despite political and public resistance. Mali’s president has similarly attempted to quell political and publish backlash against the French presence.

French forces suffered significant casualties while continuing counter-ISGS operations in Mali. Two helicopters crashed while supporting combat operations in the Menaka region of northern Mali on November 26, killing 13 commandos. The Islamic State’s West Africa Province, which represents ISGS, falsely claimed responsibility for the incident. (See Figure 1.)

Forecast: French and Sahelian forces will continue operations against ISGS in Menaka, likely forcing the group to go to ground and temporarily shift its operations to Niger and Burkina Faso, as it has done in the past. The AQIM-affiliated faction in this region will exploit a focus on ISGS to advance its grassroots efforts to establish de facto control of local populations in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso in this period. (As of December 3, 2019)

Figure 1. Operation Bourgou IV and Major Salafi-Jihadi Attacks in the Sahel: August - November 2019

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute

The situation in Burkina Faso continues to deteriorate as intercommunal violence escalates in the east and security degrades in the north. Salafi-jihadi attacks in eastern Burkina Faso have targeted self-defense militias drawn from the majority Mossi ethnic group, sparking *reprisal attacks by these militias against the Fulani population, an ethnic group often accused of collaborating with the Salafi-jihadi groups. An assassination of a local militia leader likely by Salafi-jihadi militants on November 17 prompted militiamen to kill at least 20 Fulani and detain many others. Separately, Salafi-jihadi militants killed 14 worshippers at a church in eastern Burkina Faso on December 1. The increase in interethnic and interconfessional violence is intended to isolate the Muslim communities and in turn induce them to accept protection from Salafi-jihadi groups.

Meanwhile, AQIM’s Sahelian affiliate, Jama’a Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), is establishing itself as the de facto governing power in Soum Province in northern Burkina Faso. JNIM framed its attacks on security forces near the provincial capital as a defense of the population, a sign that the group is exploiting the poor relationship between locals and security forces. JNIM has also been openly preaching and providing aid to local residents.

Forecast: Intercommunal violence will increase in the next six months and eastern Burkina Faso will destabilize similarly to northern Burkina Faso. Salafi-jihadi groups will gain access to local gold mining, increasing their funding for operations throughout the Sahel. (As of December 3, 2019)

North Africa

Libya

The protracted battle for Tripoli, Libya’s capital, is degrading security across Libya. The Libyan National Army (LNA) militia coalition, led by Khalifa Haftar, launched an offensive to seize Tripoli in April 2019 and has yet to breach the city’s defenses, even with significant support from Russia, the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. These states and rivals, such as Turkey, are exploiting the Libya conflict to pursue geopolitical and ideological goals. The civil war will benefit the Salafi-jihadi movement in Libya and has destabilized parts of the country where Salafi-jihadi militants are active, notably the southwest.

The LNA continued its offensive on Tripoli amid international efforts to secure a cease-fire. LNA forces intensified air operations in northwestern Libya in the days following a US Department of State statement strongly condemning the LNA’s offensive and Russia’s involvement in the conflict on November 14. Airstrikes on November 19 struck a biscuit factory in Tripoli and caused further civilian casualties in Misrata, the home city of many anti-LNA militias active on the Tripoli front line. The LNA stated that the airstrike in Misrata targeted armored vehicles and weaponry delivered by Turkey.

The LNA signaled its intent to continue pursuing a military solution by declaring a “no-fly zone” over Tripoli on November 23. US Africa Command reported the loss of an unarmed surveillance drone over Tripoli on November 21. US defense officials stated that Russian mercenaries supporting the LNA may have been involved in the drone’s downing. The LNA claimed to shoot down an Italian drone over Tarhouna, northwestern Libya, on November 20, but Italian officials reported that the drone crashed during migration-related surveillance activities.

US and European diplomats have intensified efforts to bring about a cease-fire in Tripoli. Senior American officials met with Haftar to discuss a cease-fire and curbing Russian influence on November 24. On November 20, the Italian ambassador to Libya met with the head of the Government of National Accord (GNA)–aligned High Council of State to discuss preparations for an international conference on Libya in Berlin, Germany, in Spring 2020. The UN Security Council called on all countries to observe Libya’s much-violated arms embargo on December 2 after a UN report highlighted violations by the UAE and Jordan (on the LNA’s side) and Turkey (on the GNA’s).

Turkey struck an agreement with the UN-backed GNA to advance Turkish maritime and energy interests. The GNA and Turkey signed a security cooperation agreement on November 27 denoting new maritime boundaries that infringe on areas claimed by Greece and Cyprus in preparation for a gas pipeline through the eastern Mediterranean. The “defense pact” also grants Turkey the right to operate in Libyan airspace and territorial waters and build military bases inside Libya. The GNA has become increasingly dependent on Turkish military support, particularly drones, since the LNA offensive on Tripoli began in April.

The national conflict spilled into southwestern Libya over control of oil fields. GNA–aligned forces seized the al Feel oil field on November 27, prompting the LNA to respond with airstrikes. The strikes disrupted oil production at al Feel. An LNA or pro-LNA strike caused civilian casualties in a nearby town. The incident mirrors a pro-LNA drone strike in the southwest in August that killed dozens of civilians.

The Islamic State is benefiting from continued conflict. Libyan militia commanders reported the arrest of eight Islamic State members in Sirte, the central Libyan city that the group controlled in 2015–16, in recent weeks and asserted that Islamic State sleeper cells remain in the city. GNA-aligned militias claimed that the threat of LNA airstrikes prevents them from patrolling in southern parts of Libya, where the Islamic State is active.

Forecast: The LNA and its backers will continue to pursue a military victory even as diplomatic pressure intensifies. GNA-aligned militias in Tripoli may switch sides or strike a deal with the LNA, delivering at least a partial victory to Haftar without greater outside support for his adversaries. Haftar will not stabilize the country, however, and anti-Haftar insurgencies will occur in multiple areas. (As of December 3, 2019)

Algeria

Algeria will hold elections on December 12 that will not solve the country’s legitimacy crisis. Algeria’s political situation has been deadlocked since protests began in February and led to the ouster of longtime President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April. Protesters oppose elections without dialogue and are demanding the removal of Bouteflika-era political figures, greater press freedom, and the release of political prisoners. Military and political leaders support elections as a step toward resolving the political crisis. The leading presidential candidates are Bouteflika-era figures and have struggled to campaign due to backlash from protesters.

Salafi-jihadi groups in Algeria ended long periods of dormancy in an attempt to capitalize on the unrest.

- AQIM claimed a clash with security forces west of Algiers as its first attack in Algeria since February 2018. A November 20 statement from the head of the group’s media department asserted support for Algeria’s peaceful protests and promised to forgo any military action that would jeopardize the protests. The statement called on protesters to embrace armed resistance as a necessary facet of their uprising.

- The Islamic State in Algeria conducted its first attack in Algeria since 2017. The group clashed with Algerian soldiers in southern Algeria on November 18 and claimed the attack on November 20. Algerian military sources reported that a militant killed in the clashes was the cousin of Sultan Ould Badi, a Salafi-jihadi leader with ties to ISGS and AQIM who surrendered to Algerian authorities in late 2018.

Forecast: The political deadlock in Algeria is unsustainable and will reach a turning point, but it is not clear if this will occur in the coming months or years. The December 12 elections will likely occur with low turnout and establish a puppet government while the military retains control. In one case, violent unrest may occur if security forces crack down more aggressively on protesters or elements within the protest movement take violent action. Such an escalation could set conditions for a full military takeover or an insurgency, which Salafi-jihadi militants in turn would attempt to exploit. Alternatively, protesters’ momentum may be stifled over time, setting conditions for a future legitimacy crisis and unrest. In the most optimistic but unlikely case, the state could undertake substantive reforms that resolve the legitimacy crisis. (As of December 3, 2019)

East Africa

Somalia

Al Shabaab’s insurgency in Somalia is stalemated, but this stalemate is eroding in al Shabaab’s favor as African Union peacekeeping forces draw down ahead of their scheduled withdrawal in 2021. Domestic political turmoil in multiple Somali Federal Member States is drawing the attention of security forces away from counter–al Shabaab efforts and creating new opportunities for instability that al Shabaab will likely exploit.

US officials believe that an American al Shabaab member is currently the highest-ranking US citizen fighting overseas with a terrorist organization. A US court unsealed a new indictment against Jehad Serwan Mostafa on December 2. The FBI previously placed Mostafa on its Most Wanted Terrorist List and the US Department of State issued a $5 million reward for information on him in 2013. Mostafa joined al Shabaab around 2006 and is currently a leader in the group’s explosives department. Al Shabaab has increased its production of homemade improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in recent years and conducted more IED attacks in 2019 than ever before.

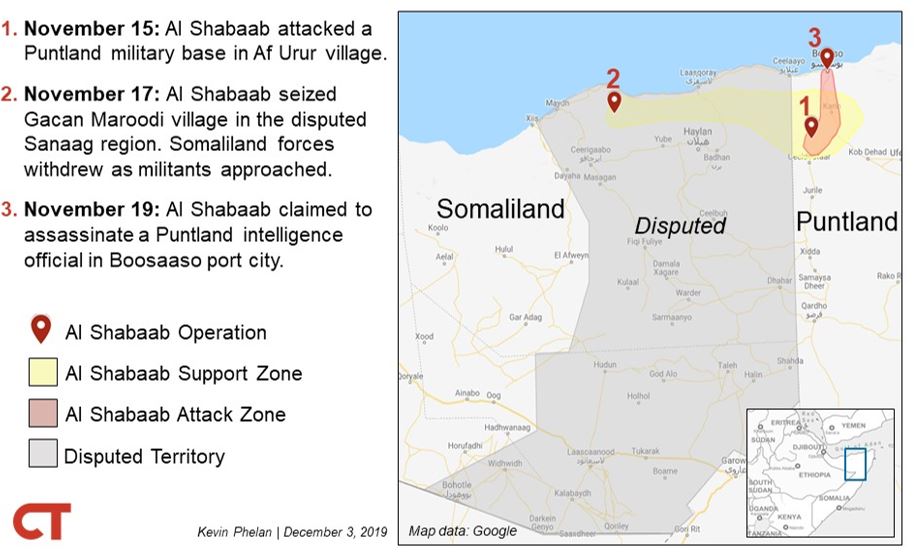

Al Shabaab conducted a rare operation in Somaliland. Somaliland is a self-declared state in northern Somalia that is more stable than the rest of Somalia and has largely avoided al Shabaab attacks in recent years. The group seized a village in a disputed territory between Somaliland and neighboring Puntland State, where al Shabaab has a small presence. (See Figure 2.)

Forecast: Al Shabaab will not seize significant territory in Somaliland but will occasionally attack security forces in the disputed border area over the next 12 months while boosting recruitment from local clans. Somaliland will conduct occasional counterterrorism operations in this area to bolster its image as it seeks international recognition. Somaliland and Puntland will continue to focus their security resources on the border conflict, allowing al Shabaab to maintain its support zone in remote parts of Puntland and eastern Somaliland. (As of December 3, 2019)

Figure 2. Al Shabaab Conducts Rare Attack in Somaliland

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute.

Competition between Ethiopia and Kenya is increasing in Jubbaland, a Federal Member State in southern Somalia where al Shabaab maintains its main staging area for operations. The Somali Federal Government (SFG)—the primary US counterterrorism partner in Somalia—has tense relationships with most of the five Federal Member States that is compounded by regional competition. Kenya and Ethiopia have become more involved in a long-running competition between Jubbaland President Ahmed Madobe and the SFG since August, when Madobe *declared himself winner of a disputed state election.

Kenya supports Madobe, while Ethiopia backs the SFG. Ethiopian forces operating separately from the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) are likely responsible for the *arrest of some of Madobe’s ministers in early November. In response, Jubbaland politicians *called for a withdrawal of all non-AMISOM Ethiopian forces. Kenya may be attempting to undermine Ethiopia by increasing its influence in Ethiopia’s restive Somali region. Kenya likely *hosted a meeting between Madobe and a former rebel group from Ethiopia’s ethnic Somali community in late November.

Forecast: SFG and Jubbaland security forces will likely clash in the next three months. Ethiopian forces may attempt to arrest Madobe, which will likely prompt direct but limited Ethiopian-Kenyan clashes. Al Shabaab will expand its support zone in the Jubba River Valley in the event of a sustained conflict between Madobe and the SFG. (As of December 3, 2019)

Southeast and Central Africa

The Salafi-jihadi movement has made inroads in southeastern Africa and will strengthen if current conditions persist. A nascent Salafi-jihadi insurgency in Mozambique may spread to its larger neighbor, Tanzania, risking greater regional destabilization. Some militants in Mozambique have *pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and operate under the administrative heading of the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province. Members of a separate militant group active in parts of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) also operate under this province’s heading.

Islamic State–linked insurgents in Mozambique conducted their first reported attack in neighboring Tanzania on November 13. The attack was unsophisticated but is an early warning of the threat that the Salafi-jihadi movement poses to Africa’s sixth-largest country. Tanzania has never experienced an organized Salafi-jihadi insurgency but the country is a refuge and recruiting ground for Salafi-jihadi militants operating in East Africa. [For more on the Salafi-jihadi threat to Tanzania and its regional implications, read James Barnett’s warning update.]

The Congolese military launched an offensive against the Islamic State–linked Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) in eastern DRC. Congolese forces *claimed to kill one of the ADF’s top commanders in North Kivu province on November 29. ADF forces have increased attacks against civilians in the province since the offensive began on October 30. Local residents began protesting against the Congolese military and UN peacekeepers on November 24 in response to recent attacks.

Forecast: The offensive will degrade the ADF’s capabilities in the near term, but continued instability in eastern DRC will allow the group to retain sanctuaries and reconstitute over the next 12 months. The ADF will also attempt more high-profile attacks outside of eastern DRC, including attacks against Western interests in Central Africa, over the next 12 months. (As of December 3, 2019)