Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.

Salafi-jihadi groups, including Islamic State and al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) affiliates, are degrading and replacing governance in West Africa’s Sahel region. The recently released State Department “Country Reports on Terrorism” highlight the rapid escalation in Salafi-jihadi militant violence in the Sahel, particularly these groups’ ability to manipulate local ethnic conflicts to gain popular support. A series of major attacks on military and economic targets in Mali and Burkina Faso indicate that Salafi-jihadi groups are growing increasingly lethal and making progress in their long-term effort to drive out Western presence and degrade and replace local governments.

This trend will reverberate beyond the Sahel; local Salafi-jihadi groups underpin the global Salafi-jihadi movement and advance the goals of organizations such as the Islamic State. The Islamic State’s affiliates in West Africa pledged allegiance to its new leader, the successor to the late Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, in early November.

The Islamic State affiliate in the Sahel, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), conducted a major attack on November 2 that showcased both an increase in ISGS capabilities and the ineffectiveness of current military-focused counterterrorism efforts in the Sahel. The assault on the Malian Army’s Indelimane camp in the Menaka region of northeastern Mali killed at least 53 Malian soldiers, one of the deadliest attacks in Mali to date. This attack is the latest in a series of deadlier-than-normal attacks in the Sahel and reflects several trends that underlie the Salafi-jihadi movement’s strengthening in this region.

- ISGS has reached a new level of tactical capability that will enable it to conduct more demoralizing high-casualty attacks, strengthening the narrative that the Malian government is powerless to protect its people. The *Indelimane attack integrated several capabilities, reaching a new level of sophistication for ISGS. The group used mortar fire, attackers on motorcycles, and a truck bomb to breach and overrun the compound. ISGS also conducted surveillance, which included using small drones, to plan the attack.

- ISGS’s integration with local and international Salafi-jihadi networks increases its effectiveness. ISGS sometimes cooperates with other Salafi-jihadi groups in the Sahel, including AQIM-affiliate Jama’a Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), which has a longer record of attacking fortified bases in the region. This overlap in Salafi-jihadi networks facilitates the transfer of expertise. ISGS’s use of commercially available drones reflects Islamic State tactics in other theaters.

- The Indelimane attack demonstrates an acute failure of a military-only counterterrorism approach. French and Nigerien forces cleared ISGS from the Menaka region in June, but the group has since returned as governance conditions remained unchanged. A Malian security source stated after the attack that the Malian Army cannot rely on the local population to help locate enemy positions.

Military-only approaches to counterterrorism, in the Sahel and elsewhere, fail because they do not account for Salafi-jihadi groups’ main goal: establishing governance. Salafi-jihadi groups in the Sahel have grown increasingly adept at exploiting local conditions such as ethnic conflict. This approach is particularly potent when vulnerable local populations are victimized by the state and security forces, allowing Salafi-jihadi groups to impose their will or even pose as these communities’ defenders.

The growing strength of the Salafi-jihadi movement is evident elsewhere in the Sahel. In Burkina Faso, an attack on a Canadian mining company convoy that killed 37 and injured 60 exposed the vulnerability of key economic positions as Salafi-jihadist and other armed groups compete for access to gold mining. In central Mali, JNIM is asserting control by terrorizing the population, destroying state institutions, and brokering a local cease-fire.

Unfortunately, this predominantly military counterterrorism approach is set to continue. Malian, Burkinabe, and French authorities announced the launch of offensive operations targeting Salafi-jihadi groups in response to recent attacks. Any gains from such operations will be temporary without policies to close the governance gaps and resolve the conflicts that Salafi-jihadi groups exploit.

The Sahel is not the only part of northern Africa where Salafi-jihadi groups are on the rise. Critical Threats Project Research Manager Emily Estelle argues in RealClearDefense that the Russian intervention in Libya will worsen the conditions that strengthen the Islamic State and al Qaeda over time. Russia-backed warlord Khalifa Haftar cannot stabilize the country. Even if he takes control, Haftar’s repressive approach will worsen the popular grievances that fuel Salafi-jihadi insurgencies.

Read Further On:

At a Glance: The Salafi-Jihadi Threat in Africa

Updated October 29, 2019

Global counterterrorism efforts are rapidly receding with the end of counter–Islamic State operations in Syria and the withdrawal of US troops in October 2019. This withdrawal sets conditions for the return of the Islamic State, even as the organization recovers from the death of its leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and other senior officials in US operations in late October. The US withdrawal has also damaged America’s reputation with current and potential counterterrorism partners wary of suffering the same fate as the abandoned Syrian Kurdish forces. The US administration also seeks to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan, a course that will likely be delayed rather than altered by the breakdown of talks with the Taliban. However, the Salafi-jihadi movement continues to make gains in Africa, including in areas in which previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement is positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations. The return of African Salafi-jihadis from prisons in Syria will likely accelerate these trends.

The Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, on the counteroffensive in Libya, and stalemated in Mali, Somalia, and Nigeria. However, conditions in the last three countries favor the Salafi-jihadi movement rather than its opponents over the next 12–18 months.

Libya’s civil war, reignited on a large scale in April, will continue to fuel the Salafi-jihadi comeback for at least the next several months, possibly allowing the Islamic State or al Qaeda to regain some of the territory they controlled before major operations against them from 2016 to 2019. The Islamic State’s comeback in Libya is part of its global effort to reconstitute capabilities after military defeats, an effort that the group’s late leader, Baghdadi, sought to galvanize in a September audio message. Stalemates in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is rapidly eroding, and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in the eyes of their people.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great power competition, a move also intended to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness — such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown.

The Salafi-jihadi movement currently has four main centers of activity in Africa: Libya, Mali and its environs, the Horn of Africa, and the Lake Chad Basin. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other place is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse. Local crises are the incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the bases for future attacks against the US and its allies.

West Africa

Mali and Burkina Faso

The Salafi-jihadi movement is expanding more rapidly in the western Sahel than in any other African region as communal violence and state fragility spread. The movement’s epicenter in this region is Mali. Salafi-jihadi groups are active in the country’s north and have spread into the country’s center, where ethnic-based violence has increased in the past two years. Neighboring Burkina Faso is destabilizing rapidly as Salafi-jihadi groups take root in its north and east. Several Salafi-jihadi factions are cooperating, particularly in the Mali–Burkina Faso border area, to drive out security forces and establish themselves as the de facto governing power. The violence is causing a humanitarian crisis that has included retaliatory massacres of civilians in central Mali and mass displacement in Burkina Faso.

ISGS claimed responsibility for an attack on a Malian Army base in northeastern Mali’s Menaka region that killed more than 50 soldiers, signaling ISGS’s return to Menaka and increased lethality. The group used a truck bomb and artillery to breach and overrun the Indelimane base on November 1. It reportedly used drone surveillance to prepare for the attack. ISGS also claimed a roadside bombing that killed a French soldier in Menaka on the following day. Menaka is a historic hub of ISGS activity, but its operations there had declined following a French-Nigerien operation in June. This attack indicates that the effects of that operation were temporary and that ISGS has reestablished itself in Menaka and neighboring areas.

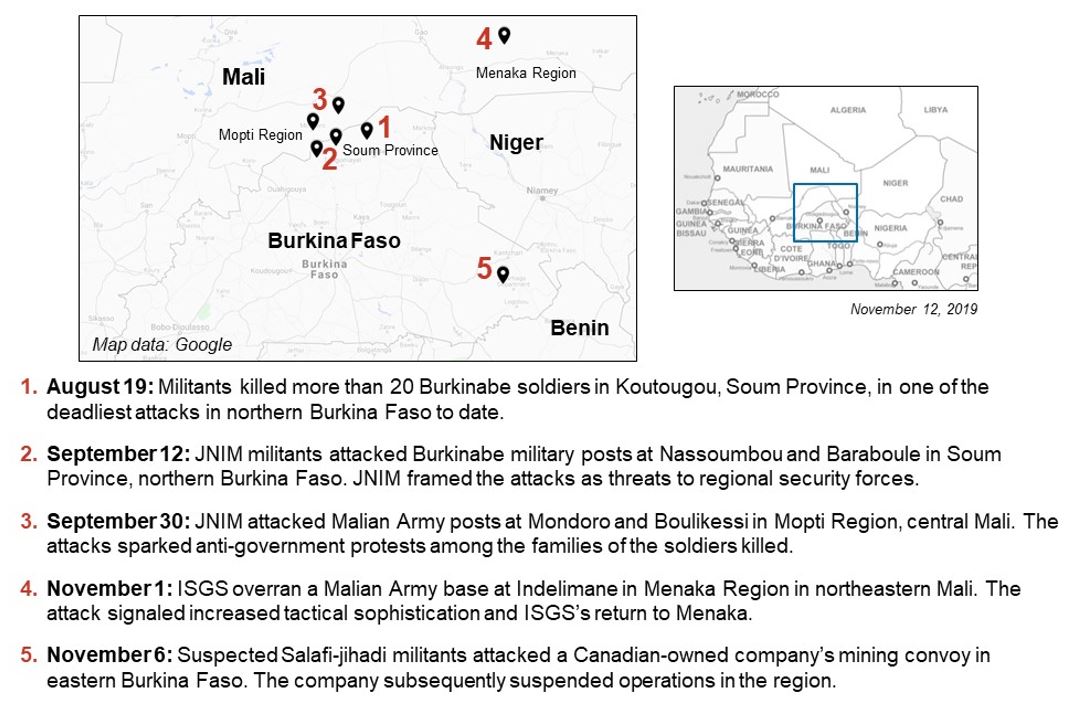

The Indelimane attack is the latest in a series of high-casualty attacks on military and economic targets in the Sahel. Militants attacked a convoy carrying employees of the Canadian mining company SEMAFO in eastern Burkina Faso on November 6. The attack killed and injured scores of civilians, causing the company to suspend its operations in the area. Violent incidents against mining companies have increased as insecurity spreads in Burkina Faso, including three others against SEMAFO in 2019. Other major attacks in recent weeks include a dual attack on Malian military positions near the Burkinabe border on September 30. (See Figure 1.)

Worsening security is causing backlash against national governments and foreign companies in the Sahel. The wives of soldiers killed in the September 30 attacks in Mali have protested insufficient support for Malian troops and criticized French and UN peacekeeping forces in Mali. Victims of the SEMAFO convoy attack in Burkina Faso have criticized Burkinabe authorities and SEMAFO for lack of support.

Figure 1. Major Salafi-Jihadi Attacks in the Sahel Since August 2019

Source: Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute

In response to recent attacks, security forces are doubling down on a military response to the Salafi-jihadi threat. The Malian Army changed its operational posture by withdrawing from isolated camps near the Niger and Burkina Faso borders and launching a major counteroffensive against Salafi-jihadi groups in central Mali. The Burkinabe military is also intensifying its operations by partnering with French forces for a counterterrorism operation titled “Bourgou IV” in the shared border region of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. The French defense minister announced that European special forces will assist Sahelian militaries in Operation Takuba beginning in 2020.

Forecast: The Malian Army’s response to recent attacks will backfire by increasing anti-government grievances among marginalized populations in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. Salafi-jihadi groups may relocate or go to ground in response to military pressure but will resume infiltrating populations within the year, especially if security forces continue to withdraw from forward positions. Salafi-jihadi groups remain on track to establish de facto governance and ultimately a proto-state in the shared border region of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. (As of November 13, 2019)

The Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWA) pledged allegiance to the group’s new leader following the death of Abubakr al Baghdadi. ISWA’s media office promotes activities by ISGS and the former Boko Haram splinter known as ISWA, which operates in the Lake Chad region. It released photosets from both groups. ISWA is the latest in a series of Islamic State affiliates that have pledged allegiance to Baghdadi’s successor, Abu Ibrahim al Hashimi al Quraishi. The Islamic State in Libya has notably failed to pledge so far, likely indicating that a series of American airstrikes in September disrupted the group’s media capabilities.

JNIM emir Iyad Ag Ghali participated in a coordinated al Qaeda media campaign by praising an attempted al Shabaab attack on an American base in Somalia. Ag Ghali also praised recent JNIM attacks in Mali and Burkina Faso in a November 9 statement. Al Qaeda’s General Command and al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula also praised the late September attack. This is Ag Ghali’s first public statement in 2019.

East Africa

The emir of al Shabaab, al Qaeda’s East African affiliate, appeared on video for the first time calling for attacks on US interests. Ahmad Umar, aka Abu Ubaidah, appearing with his face blurred, praised al Shabaab militants who attacked a US airbase in Somalia in late September. Al Qaeda’s General Command, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and the al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb affiliate in the Sahel have praised the attack to highlight al Qaeda’s commitment to attacking Western interests. The video of Umar may also seek to dispel rumors of his ill health. This was Umar’s second public statement in two months after EDITORS' NOTE: CORRECTIONA previous version of this brief incorrectly stated that Umar had not given a speech since 2016.more than a year without releasing an audio speech. [For more on al Shabaab’s October 1 attack on a US base in Somalia, read the October 1 Africa File.]

The Islamic State in Somalia *pledged allegiance to Abu Ibrahim al Hashimi al Quraishi, the successor of Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and new leader of the Islamic State, amid a wave of new pledges from Islamic State affiliates worldwide. The Somali group published photos of fighters pledging allegiance to Abu Ibrahim on November 4. Islamic State affiliates in Yemen, Bangladesh, the Sinai Peninsula, and Pakistan also released pledges on November 4.

Al Shabaab conducted more improvised-explosive-device (IED) attacks in 2019 than in any other period in the group’s history. A November 2019 UN panel of experts report noted that al Shabaab increased its IED attacks by roughly one-third in 2019. The panel also confirmed that al Shabaab has been producing homemade explosives since at least 2017. The group historically did not have this capability and instead modified captured military-grade explosives. The panel also raised concerns about al Shabaab’s infiltration of Somali federal and local government ministries.

Al Shabaab’s insurgency in Somalia is stalemated, but this stalemate is eroding in al Shabaab’s favor as African Union peacekeeping forces draw down ahead of their scheduled withdrawal in 2021. Domestic political turmoil in multiple Somali Federal Member States is drawing the attention of security forces away from counter–al Shabaab efforts and creating new opportunities for instability that al Shabaab will likely exploit. The Somali Federal Government (SFG)—the primary US counterterrorism partner in Somalia—has tense relationships with most of the five Federal Member States. For example, a prolonged political crisis in Galmudug State in north-central Somalia risks drawing Africa Union Mission to Somalia, SFG, and local security forces away from counter–al Shabaab efforts in that region. Clashes between SFG forces and a local militia *resumed in Galmudug in October and early November.